Category Archives: Romania

EU 2014: Poland to Slovakia

This next post on the May EP elections covers Poland, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia – Slovenia, which had legislative elections on July 13, will be covered separately.

Note to readers: I am aware of the terrible backlog, but covering the EP elections in 28 countries in detail takes a very long time. I will most likely cover, with significant delay, the results of recent/upcoming elections in Colombia (May 25-June 15), Ontario (June 12), Indonesia (July 9), Slovenia (July 13) and additional elections which may have been missed. I still welcome any guest posts with open arms :) Thanks to all readers!

Poland

Turnout: 23.83% (-0.7%)

MEPs: 51 (nc from Lisbon)

Electoral system: Open-list PR, 5% threshold (13 EP constituencies)

PO (EPP) 32.13% (-12.3%) winning 19 seats (-6)

PiS (ECR) 31.78% (+4.38%) winning 19 seats (+4)

SLD-UP (S&D) 9.44% (-2.9%) winning 5 seats (-2)

KNP (NI) 7.15% (+7.15%) winning 4 seats (+4)

PSL (EPP) 6.8% (-0.21%) winning 4 seats (nc)

SP (EFD) 3.98% (+3.98%) winning 0 seats (nc)

E+ – TR (S&D/ALDE) 3.58% (+3.58%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PR (ECR) 3.16% (+3.16%) winning 0 seats (nc)

RN 1.4% (+1.4%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Greens (G-EFA) 0.32% (+0.32%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Direct Democracy 0.23% (+0.23%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Samoobrona 0.04% (-1.42%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Poland, the sixth most populous country in the EU and the largest of the ‘new’ member-states from the Eastern enlargements, has become one of the major players in the EU and certainly the most important of the new member-states. Although Poland’s GDP per capita does not make it the ‘richest’ of the post-2004 member-states, it has the biggest economy of all post-2004 members (and the eight-largest in the EU). Under the present Polish government, more pro-European than its predecessor, Poland has taken a leading role in European politics, especially on matters related to Eastern Europe and Russia.

From 1991 until about 2007, Polish politics – similar to that of most other Eastern European post-communist states – were unstable, characterized by weak political parties coming and going, unpopular governments governing in difficult circumstances leading to a very high degree of anti-incumbency (until 2011, no incumbent government won reelection) and very large swings from election to election. The story of Poland’s post-communist left, led by the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), is an excellent example of this instability. The left enjoyed a resurgence in the 1990s, with the election of Aleksander Kwaśniewski to the presidency in 1995, defeating incumbent President and anti-communist resistance icon Lech Wałęsa; and then with the landslide victory of Leszek Miller’s SLD in the 2001 legislative elections, where the left won 41% of the vote against a divided and demoralized incumbent right (the incumbent right-wing government, Jerzy Buzek’s AWS, won only 5.6% and lost all 201 of its seats). However, Prime Minister Leszek Miller and his party quickly became extremely unpopular due to economic policies enacted to counter high unemployment, debt and economic stagnation and by major corruption scandals, notably Rywingate (the bribery of senior politicians, likely acting on behalf of Miller and his government). Therefore, in the 2005 legislative elections, the SLD collapsed to 11% and the left has been unable to recover from its defeat.

Since 2007, politics have stabilized around two major parties complemented by minor parties; both major parties are on the right of the spectrum, although grouping the two together as ‘conservative’ parties is deceptive and obscures the wide schism – ideological and cultural – between the two parties and their supporters. Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s Civic Platform (PO), which has held government since 2007 and the presidency since 2010, is a centre-right liberal conservative and pro-European party. At the outset, PO, which was founded in 2001, was a very liberal (neoliberal) party promoting aggressive economic reforms including privatizations, a flat tax, decentralization, reduction of the size of government and structural reforms. In government, however, Tusk’s party has widely been accused of having morphed into a centrist ‘party of power’ having lost its initial reformist zeal and instead motivated only by securing reelection – which it did in 2011, becoming the first Polish government to win reelection. To some extent, Tusk’s PO has been unwillingly assisted by his main opponent, Law and Justice (PiS), a nationalist-conservative, socially conservative and fairly Eurosceptic party led by former Prime Minister Jarosław Kaczyński (2006-2007), the identical twin brother of former President Lech Kaczyński (2005-2010), who was killed in April 2010 when his presidential plane crashed while landing in Smolensk (Russia), killing all 96 passengers and crew. PiS’s very conservative and nationalist rhetoric, influenced by the very powerful and traditionalist Catholic Church in Poland, appeals to a particular segment of the Polish electorate, but at the same time it is very off-putting to the other half of the Polish electorate. PiS has not won a national election in Poland since 2007.

Therefore, although both PO and PiS are parties of the right, there are real and important ideological differences between the two. Economically, PO ostensibly supports European liberal policies, including privatizations, low taxes, compliance with EU budgetary rules and, in the long-term, adoption of the euro; on the other hand, PiS has, since its 2007 defeat, shifted towards interventionist and populist policies and opposed the government’s reforms (although, it should be noted, PiS was quite economically liberal in its own right when in power). The PO is strongly pro-European, and Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s name comes up every now and again in speculation for a potential top EU job. PiS is a Eurosceptic or anti-federalist party – it does not support withdrawing from the EU (a fringe opinion in Poland) but, similar to the British Tories (PiS are the Tories’ most important European allies), opposes a ‘federalist’ EU and often argues against further devolution of national powers to the EU in the name of Polish sovereignty. PiS was placed in an awkward position last year, as an ECR member and Tory partner, after David Cameron said that he would work to change EU regulations to withhold welfare benefit payments to EU migrants working in the UK with their families back home (and specifically mentioned Poles, one of the largest migrant communities in the UK).

PiS is often strongly nationalist – it has regularly engaged in anti-German and anti-Russian rhetoric, and a good chunk of the party – including Jarosław Kaczyński – believe that the plane crash which killed President Lech Kaczyński in Russia in 2010 was a Russian conspiracy. Law and Justice is vociferously anti-communist – it wishes to take lustration even further, by banning all university professors, lawyers, journalists and managers of large companies from holding their jobs if they are found to have collaborated with the communist-era secret service. Poland is one of the EU’s most socially conservative countries, and the Catholic Church – which in Poland tends to be highly conservative and somewhat politically active – retains a good deal of influence, although there is a strong secular or anti-clerical movement as well. PiS is the most socially conservative party, strongly opposed to abortion (which is already illegal with exceptions maternal life, mental health, health, rape, and/or fetal defects), same-sex marriage (and oftentimes hostile to homosexuality in itself) and IVF; PO is internally divided, with a powerful conservative faction opposed to abortion and same-sex marriage, meaning that PO has – until recently – largely made sure to not alienate the Church or conservatives in the party.

Poland was the only EU member-state to escape recession in 2009, with +1.6% growth, according to The Economist “thanks partly to luck and partly to a mixture of deft fiscal and monetary policies, a flexible exchange rate for the zloty, a still modest exposure to international trade and low household and corporate debt”. Poland benefited greatly from EU accession in 2004, and continues to receive billions of euros worth of development funds. Fairly strong growth in 2010-2012 (averaging about 4%), a fairly low debt (51% of GDP in 2009, now 57%) and a government generally well regarded by its EU partners (notably neighboring Germany) have given Poland extra weight in the EU.

In 2011, Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s PO was reelected to an unprecedented second term, winning 39.2% against 29.9% for PiS, with both parties losing about 2% of the vote from the 2007 election. Tusk retained power, in coalition with the small agrarian Polish People’s Party (PSL), a venal and opportunistic party which is amenable to a coalition with anybody to protect its rural voters’ interests and its own ministerial portfolios. In 2010, the PO had won the presidency in snap elections held after the death of President Lech Kaczyński. PO candidate Bronisław Komorowski defeated Jarosław Kaczyński 53% to 47%, and his election has inaugurated a much calmer relation between the Prime Minister and the President – between 2007 and 2010, Tusk had often clashed with his nemesis, Lech Kaczyński, and used the latter’s intransigence and vetoes to deflect blame for the lack of reformist vigour from his government.

Tusk’s reelection, and a friendly relationship between the presidency and government, boosted hopes that the new government would prove more ambitious in its agenda. Upon his reelection, Tusk outlined a reformist agenda with austerity measures to reduce Poland’s large deficit (7.8% in 2010 and 5.1% in 2011) and structural reforms, notably to the pension system. In 2012, the government passed a pension reform which will increase and equalize the retirement age for men and women to 67 by 2040 (currently, men retire at 65 and women at 60), despite major protests outside Parliament. PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński embraced the protests, enthusiastically proclaiming that the crowds reminded him of his earlier glory days in the anti-communist Solidarity trade union. The opposition criticized PO for reneging on an election promise and forcing reform without consultation, but the opposition’s motion to hold a referendum on the reform was shut down by the PSL, the loyal ally which sided with PO in exchange for minor concessions on early partial retirement. Other reforms were also met with significant push-back: measures to cut the previleges of protected workers (journalists, professors), moves to liberalize a number of regulated professions while a bill to allow the state to partially cover IVF costs for both married and unmarried women faced significant opposition from the Catholic Church but also a socially conservative faction of PO led by then-justice minister Jarosław Gowin. The hardliners in the Catholic Church had at one time threatened to excommunicate any MPs who voted for anything other than banning IVF, which they described as ‘refined abortion’.

The government faced a very tough time in 2013. Economic growth has slowed, to 2% in 2013 and a projected 1.6% in 2014. The government has been assailed from every angle for a whole number of reasons. PO has again been accused of having lost its reformist energy, and focusing increasingly on what it set to be a tough fit for reelection for 2015 and eschewing more ambitious structural reforms. A recent OECD report called on Warsaw to close the productivity gap, severely trim a bloated public sector, invest in growing industries, boost productivity, liberalize labour laws to make it easier to fire employees, push Polish firms to become globally competitive and improve the ease of doing business in Poland (the country often gets poor marks, compared to its Eastern European partners, on ‘business-friendliness’ or ‘ease of doing business’ indexes) by tackling corruption and reducing red tape. Labour force participation remains low by EU levels, and Poland faces a demographic problem in the long-term because of its low birth rate and emigration which is still high. The OECD and liberal economists have also faulted the government for dragging its feet on privatization, criticizing its tendency to declare large parastatals as ‘strategic’ to prevent them from being privatized. While foreign investors and financial institutions point out the lack of reformist energy, at home, the government is criticized for the content of its austerity-minded policies and reforms (notably to labour laws). With an increasingly sluggish economy and high unemployment (9.6%, was over 10% for most of 2012 and 2013), Poles have been gloomy about the economy and increasingly unhappy with a government which seems to spend more time on ineffective crisis management than long-term reforms.

Tusk also needed to attend to divisions within his party and to take care of an increasingly prickly and inconvenient justice minister, Jarosław Gowin, the leader of a socially conservative strand in PO which clashed with Tusk and liberals on issues such as IVF and civil unions. In February 2013, Poland’s lower house, the Sejm, debated three civil union bills, and all three bills (one of which was proposed by a PO member) were voted down, with Gowin leading 46 PO MPs to vote against the PO proposal. The debate was marked by homophobic comments from PiS MPs. In April 2013, Gowin was finally sacked after he said that German scientists were buying Polish embryos from IVF procedures and using them for scientific experiments. His insensitive (especially given history between Poland and Germany) and provocative statement rattled Germany and was the last straw for Tusk, who dismissed Gowin from cabinet a week later. Gowin challenged Tusk for the PO leadership later in 2013, winning 20% of the vote, and left the party shortly thereafter. In December 2013, Gowin founded a new splinter party, Poland Together (PR). The party claims to represent the PO’s original social conservative and neoliberal (tax cuts, deregulation, fiscal orthodoxy) roots, with an added dose of so-called ‘Eurorealism’. It teamed up with recently-disbanded Poland Comes First (PJN), a failed 2010 moderate free-market splinter from PiS (2.2% in the 2011 elections). PR had four MEPs in the old EP – one from PO, one from PiS and two from PJN – who sat in the ECR group.

Responding to the troubles, Tusk tightened his grip on the PO by sidelining PO deputy leader Grzegorz Schetyna and then shuffling his cabinet in November 2013. Jacek Rostowski, his finance minister since 2007, who had received credit for his good management of the economy in the 2008-9 global recession but was facing flack for unpopular reforms, was replaced (only months after a February promotion to Deputy Prime Minister) by Mateusz Szczurek, a young economist. Elżbieta Bieńkowska, the minister of regional development, received a major promotion to Deputy Minister and a super portfolio of infrastructure and development, focused on managing new EU funds (Poland was a major beneficiary in the latest EU 2014-2020 budget).

The opposition PiS has made major gains over the past year, with a consistent advantage over PO in polls and two victories in senatorial by-elections in 2013. However, Kaczyński’s party has hesitated between tried-and-true inflammatory and polarizing rhetoric or trying its hand at a soothing, conciliatory strategy. Playing on the unpopularity of the government’s reforms, PiS reached out to those threatened by lay-offs by promising to roll back Tusk’s reforms and increased benefits for the poor – a populist and dirigiste platform similar to that which PiS had in 2011 (it had promised tax cuts for families, a two-layered income tax to replace the flat tax and opposed cutting welfare spending). In 2013, PiS successfully focused on ‘bread and butter’ socioeconomic concerns and landed some heavy blows on the government. However, there’s still been plenty of drama and traditional fire-breathing stuff from PiS. Every now and again, Kaczyński or a PiS parliamentarian brings up the 2010 Smolensk plane crash which killed Lech Kaczyński and alleges a Russian conspiracy. A good chunk of PiS’ base loves the Russian conspiracy theories, but to other voters, it often comes out as craziness. Because Kaczyński continues to be a polarizing figure, PO has managed to retain sizable support despite a clear dip in its popularity.

Kaczyński did fight off a challenge from his right, from Zbigniew Ziobro, a former justice minister and MEP originally seen as Kaczyński’s dauphin. However, after the 2011 defeat, as Ziobro criticized Kaczyński’s leadership, he and some colleagues were expelled from PiS. Ziobro founded Solidary Poland/United Poland (SP) in March 2012, a hardline social conservative (pro-life, anti-gay marriage) and Eurosceptic party. The party had 4 MEPs in the old EP, including Ziobro, and they had left the PiS’ ECR group to join EFD, because of ECR’s liberal stances on gay marriage and belief in global warming.

On the embattled left, the SLD suffered a historic defeat in 2011, with only 8.2% and fifth place behind the Palikot Movement, a new flash-in-the-pan anti-clerical and very socially liberal (pro-gay marriage, drug legalization, free condoms, legalizing abortion) led by eccentric maverick PO dissident Janusz Palikot, which finished third with 10% and 40 seats. Former Prime Minister Leszek Miller (2001-2004), whose tenure as Prime Minister was marked by unpopular orthodox liberal economic polices, pro-American stances (along with centre-left President Kwaśniewski, Poland joined the American-led coalition in the invasion of Iraq in 2003) and corruption scandals, returned to active politics and the SLD as the party’s leader. Miller has criticized the government’s policies from the left and taken on a calm and predictable image, but there were constant rumours that the SLD would join the governing coalition. This did not materialize, due to reluctance on the part of both the PO and the SLD, but there are still rumours that it’s only been delayed till after the 2015 elections.

The Ukraine crisis shuffled the cards ahead of the EP elections. Poland has a difficult history with Russia, and the country has been a strong supporter of an independent Ukraine since 1991, has actively spearheaded efforts for EU engagements with Eastern European countries such as Ukraine and successive Polish governments have usually taken strongly pro-American positions. Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s government usually was friendlier and more diplomatic towards Russia than the opposition PiS, and the 2010 Smolensk plane crash led to a significant thaw in Warsaw-Moscow ties – President Kaczyński and senior Polish politicians, bureaucrats and military personnel on the flight had been travelling to a memorial for the 70th anniversary of the 1940 Katyn massacre. After the tragedy, the Russian State Duma passed a motion recognizing that Joseph Stalin had personally ordered the massacre. With the Ukrainian crisis and the Russian annexation of Crimea, Warsaw has taken a tough line against Russia.

Politically, inter-party unity soon disappeared as both the PO and PiS tried to benefit electorally from the Ukrainian crisis. Tusk, as the incumbent Prime Minister, took the lead to assume the role of a ‘strong leader’ and refocused the PO’s EP campaign around the issue of Polish and European security. He aptly invited Vitali Klitschko, a leading Ukrainian opposition leader (and now mayor of Kiev) to PO’s campaign launch and signed a cooperation agreement with Klitschko’s party, UDAR. The Prime Minister and other leading PO officials, such as foreign minister Radosław Sikorski, began adopting a PiS-like nationalist and anti-Russian tone which often drew parallels with Poland’s painful and tragic history during World War II. Finally, the government argued that the Ukrainian crisis highlighted its effectiveness in promoting Polish interests abroad by active membership in a strong, united and integrated EU without being Russophobic. In response, PiS claimed that the events in Ukraine vindicated its assertive policy vis-à-vis Russia and attacked Tusk’s apparently naive and shortsighted approach. PiS has long advocated a tough stance against Russia, notably during the 2008 Georgian/South Ossetian conflict, to counter Russian expansionism. However, voters largely sided with the incumbents, and PiS’ lead in polls tightened up significantly.

Although Ukraine was a major point of political debate, it failed to motivate voters to turn out in the EP elections. Poland saw, once again, some of the lowest turnout in the EU – only 23.8% of voters turned out to vote, down a bit less than 1% from 2009. Turnout was higher in the cities than in rural areas, with 35% turnout in the 4th constituency, which covers Warsaw and its adjacent suburban counties, 32.7% turnout in the city of Poznań, 35.9% turnout in the city of Gdańsk and 31.1% in Katowice.

The ruling PO won an extremely narrow victory over the opposition PiS, winning 32.1% against 31.8% for PiS – a difference of 24,325 votes. In terms of seats, both PO and PiS elected 19 MEPs. It is a significant victory, albeit narrow, for the ruling party. Although the low turnout means that these elections cannot be worth much, it is a symbolic victory for an embattled governing party in elections which are generally hard on incumbents. Like across the EU, EP elections in Poland are ‘second order’ elections in which voters often use the opportunity to punish incumbents without taking any risks, and as such they tend to be difficult for the incumbents – although in the 2009 EP election, the PO government – although at that time a young and popular government – had won a landslide, with 44.4% against only 27.4% for PiS. The symbolic victory is also important because these EP elections kicked off a string of four elections – the EP elections in May, followed by local elections in November, presidential elections in the spring of 2015 and finally parliamentary elections in the fall of 2015.

Nevertheless, it is far from all roses for PO: its EP victory has been assigned to the effects of the Ukrainian crisis, and the concomitant boost in the government’s popularity. However, as the Ukrainian crisis drags on and only worsens, the government’s popularity on the issue has fallen and the issue is ‘normalizing’ and no longer benefits the PO – in the long term, it’s hard to see Ukraine becoming a game-changing issue for the government – although the victory could provide momentum. PiS’ counter-offensive, attacking the PO’s credibility on security topics and trying to reemphasize domestic concerns, may have helped to reduce the government’s momentum, although PiS led (within the margin of error) most of the last polls before the election. Furthermore, regardless of the results, PO’s share of the vote is down significantly not only from its 2009 high-water mark but also its 2011 result.

Since the EP elections, the government has been hit by a firestorm surrounding a newspaper’s publication, in June, of secret tape recordings of several months’ worth of conversations involving current/former ministers. The interior minister asked the governor of the ostensibly independent National Bank for help in stimulating the economy and financing the deficit, and warned that investors would flee if PiS won in 2015; in exchange, the governor asked for the head of finance minister Jacek Rostowski. In another, foreign minister Radosław Sikorski – one of the leading foreign ministers in the EU – said that Poland’s alliance with the US was worthless and said that Poles had low self-esteem. The government and the secret service have searched the newspaper’s editorial office to identify the leaker and unsuccessfully tried to confiscate the editor’s laptop. Tusk has since regained control, somewhat, and won a confidence vote 237 to 203. He has resisted pressure to dismiss the interior minister and foreign minister and downplayed the significance and ethical issues raised by the recordings. PiS lost the advantage and was unable to get the opposition parties to agree with its proposal for a technocratic national unity government led by Piotr Gliński. Still, the issue has hurt and may continue to hurt the government. A June poll showed PiS leading by 9. A blow, but likely not a fatal blow for PO.

PiS’ narrow defeat is quite disappointing. Its losing streaks in national election continues – it hasn’t won a single national election since 2007, although this is likely the closest they’ve gotten to winning. Expecting to win handily because the government’s unpopularity and the traditional nature of EP elections, PiS found itself wrong-footed by PO’s skillful use of the Ukraine issue.

In additional good news for the government, PO’s quiet and undemanding junior partner, the agrarian PSL, had a decent election – holding its 2009 levels and its four MEPs – and the PSL’s new leader, Janusz Piechociński, who won the PSL’s leadership in 2012 after defeating longtime leader and former Prime Minister (in the early 1990s, with the ex-communist left) Waldemar Pawlak, survived his first electoral test. Janusz Piechociński, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of the Economy, had been criticized over his soft-mannered style and apparent failure to make an impact or make his party’s voice heard in government. Many in the PSL felt that the PSL was isolated in Tusk’s government since 2012, citing the lack of consultation with the PSL’s leader in the cabinet shuffles in February and November 2013. In general, the PSL has been rather undemanding and ‘constructive’ partner – basically, as long as the PO doesn’t touch the PSL’s ministerial portfolios or reform (as is said to be much-needed) the state-subsidized farmers’ social security system (a key niche topic for the PSL and its rural, agrarian base), the PSL doesn’t care much. Given internal dissatisfaction, the EP elections were seen as a first and decisive electoral test for Piechociński’s leadership. The PSL hovered dangerously close to the 5% threshold in some polls, leading to fears that it may fall below – but, as always, it held up well (despite low turnout in the PSL’s rural bases) and Piechociński can be happy.

On the left, the SLD did fairly poorly. The SLD won 9.4% of the vote and lost 2 MEPs, down from 12.3% and not performing much better than it did in 2011. Miller was likely hoping for a strong result in the vicinity of 15%, which would have boosted the SLD’s standings and allowed it to be taken more seriously ahead of the key elections next year (in which the SLD may be seeking to enter government). However, the silver lining for SLD here is that it has recovered its ‘traditional’ (post-2005) third place position in Polish politics. In 2015, it is very unlikely that either PO or PiS will secure an absolute majority – and if PiS wins, it is a major problem for them, because, as the makeup of regional executives show (PO leads or participates in 15 out of 16 voivodeship governments), PiS is politically isolated and has few allies (its prickly and insane far-right coalition partners from 2005-2007, the clerico-nationalist LPR and populist-nationalist Samoobrona, have both died off).

The SLD has also won the battle for control of the left, against the Europa Plus – Your Movement (E+ TR) coalition. The E+ coalition was launched by Janusz Palikot’s party – renamed Your Movement (TR) recently – and joined forces with smaller parties on the left and, most importantly, former centre-left President Aleksander Kwaśniewski (1995-2005). Kwaśniewski remains fairly popular at home and had an international standing while President, so there were high hopes for the alliance. However, Palikot faced criticism that he was uninterested by the actual coalition itself and just using it to build support for his own movement, while Kwaśniewski – who was not a candidate himself – seemed to give only half-hearted attention to the election (in April, he showed up to a campaign event reportedly under the influence of alcohol) and most recognized that, while still popular, Kwaśniewski is from a by-gone era and he has lost his appeal to Polish voters. The alliance began foundering as minor parties were wooed over by the SLD instead (such as the Labour Union, UP) and the alliance failed to attract many star candidates. Palikot’s own appeal since 2011 has predictably decreased significantly as well – his flamboyant, provocative and coarse style lost its charm quickly, and the party was embroiled in a few controversies (it lost the support of feminists after it dumped Wanda Nowicka, a pro-choice campaigner who was elected Vice Marshal of the Sejm, and Palikot removed her from the caucus and accused her of ‘wanting to be raped’).

Below the threshold, both Gowin and Ziobro’s right-wing political projects failed their first test. Ziobro’s SP did best, with just about 4%, while Gowin’s PR won only 3.2%.

The election was marked, finally, by the sudden success of Janusz Korwin-Mikke’s Congress of the New Right (KNP), an anti-establishment, anti-EU and right-libertarian movement. The KNP is the latest political avatar for Janusz Korwin-Mikke, a veteran enfant terrible of Polish politics since the 1990s. In the 2010 presidential election, he won 3.5%. He may be Europe’s closest thing to American libertarianism and Ron Paul – his support with young voters on the internet, his conservative and isolationist brand of libertarianism and his history of controversial statements. His very unusual and colourful views on political issues include: hardline opposition to the ‘communist project’ which is the EU, styling outgoing EC president Barroso a ‘Maoist’, saying that democracy is the stupidest form of government (he is a monarchist), proposing to turn the EC building into a brothel, opposition to women’s suffrage (because he says women are dumber than men), eating his tax return to protest taxes, saying that women often fake rape, arguing that the difference between rape and consensual sex was very subtle, agreeing with Putin that Poland had trained ‘Ukrainian terrorists’ and arguing that there was no proof that Hitler was aware of the Holocaust. The KNP wants to reduce the government to its very bare minimum (notably by abolishing income taxes, privatizing almost everything, abolishing tax redistribution and downsizing government), but is socially conservative – it supports the death penalty, opposes abortion, contraception, IVF, euthanasia and civil unions.

The KNP owes its success – 7.2% and 4 MEPs – to young voters. It won 28.5% of the vote with those 18 to 25. This blog post said that “some sociologists have argued that many of these voters are drawn from what social commentators sometimes refer to as ‘Generation Y’: the large numbers of young and fairly well-educated unemployed in Poland who live at home with their parents and are frustrated that the country has not developed more rapidly, with an apparent ‘glass ceiling’ of vested interests and corrupt networks stifling their opportunities.” These voters face the choice of emigration or low-skilled jobs at home. These well-educated young voters are highly active on the internet, and Korwin-Mikke is a big hit on Facebook and YouTube. Because it was an EP election, the KNP may be a flash-in-the-pan, but the KNP will try to use its success and Korwin-Mikke will use his platform in the EP (he has already promised to raise hell) to win seats in 2015 – but in a higher-turnout and high-stakes election, it is unlikely that the marginal KNP will find similar levels of support and Korwin-Mikke’s insane statements will likely be scrutinized closer by voters. Poland certainly has a long list of fleetingly successful minor protest parties who are one-hit-wonders but disappear quickly thereafter – like everybody’s favourite Beer Lovers’ Party in 1990!

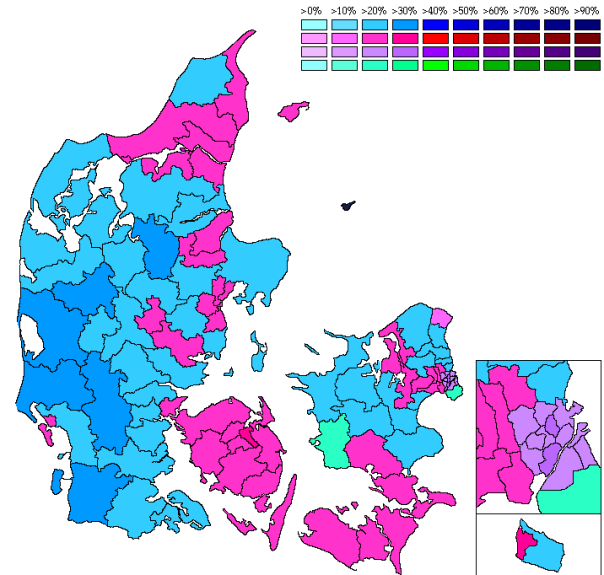

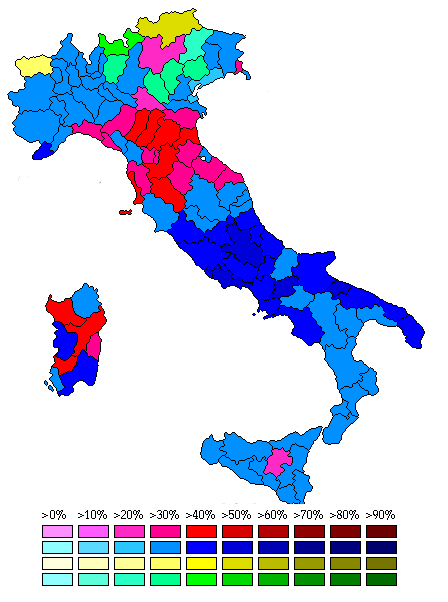

There is a strong and fascinating regional dichotomy in Polish politics. The ruling centre-right PO’s support, in orange on the map above, is largely concentrated in territories which were ruled by Prussia/Germany until 1918/1945 (what is rather interesting is how PO’s support does not correlate with the western borders of interwar Poland but rather with those of the Kaiserreich in 1914); PiS’ support, in blue on the map, is concentrated in territories which were ruled by Russia and Austria (Galicia) until 1918. Overlaying the map of the 2014 EP election on the map of the region one hundred years ago, in 1914, would produce a near-perfect correlation between German territories for PO and Russian/Austrian territories for PiS. The lingering effects of the partition of Poland as it stood in 1914 is not a mere historical coincidence: all three former imperial powers ruled their Polish territories in their own distinctive ways, built (or not) infrastructure and industry and tolerated (or not) Polish institutions such as the Catholic Church. The German territories of western Poland were slightly more urban than those in Russia or Austrian Galicia, but the infrastructure was significantly more developed and industry slightly more important (notably with coal mining and the industrial basin of Silesia, although the textile town of Łódź was Russian) resulting in a significant gap in wealth and development between the German and Russian/Austrian regions, which remained far less developed, poorer and predominantly agricultural (largely in the form of small-scale, subsistence farms). The west/east divide is extremely perceptible in 1950s maps of the Polish rail network (and even in the modern rail network). However, the 1914 German territories are no longer ethnically German – Poland’s German minority nowadays only counts about 150,000 people largely in Opole Voivodeship (formerly German Upper Silesia) – and western Poland was extensively resettled after World War II – the large German population was forcibly expelled to Germany and the region was resettled by Poles, largely from the eastern territories of interwar Poland annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945. Therefore, the modern population of most of the PO-voting western regions – especially those which were German until 1945 – have only been settled by their current inhabitants for 70 years or so. The western population therefore is far less rooted in the region, while the population of Galicia and the Russian territories have seen no comparable demographic upheavals. The former German territories, partly because of Bismarck’s kulturkampf, have been less clerical than the Austrian and Russian territories, where local authorities tolerated the influence and authority of the Polish Catholic Church; under communist rule, therefore, the communist regime likely faced less clerical resistance and challenges in the ‘recovered territories’ of the west. Under communist rule, the east also tended to remain less developed – for example, collectivization of agriculture was abandoned early on in the east but was more ‘successful’ in the west. In conclusion, earlier and more thorough industrialization, better infrastructure, relative affluence, high population mobility and lower religiosity have led to more liberal and pro-European views in western Poland while a traditional agricultural past, higher poverty, high religiosity and clerical influence, low population mobility and poor infrastructure have led to social conservatism and traditionalist views in eastern Poland. To this day, eastern Poland remains poorer than urban and western Poland, although eastern Poland has been drawing in a lot of EU funds.

This divide, however, is not absolute (not all parties, far from it, have a east-west map) or frozen in time. Nor is the “German PO vs Russian/Austrian PiS” a universal rule. The east-west divide partly covers a strong urban-rural divide. Warsaw, which was in Russian eastern Poland, is a PO stronghold: the party won 43.8% against 26.5% for PiS in the Polish capital this year (a much larger margin, I will add, than those in ‘rural’ western counties). Other large eastern cities join the western cities in voting for PO, often by significant margins. The eastern city of Łódź gave 46.4% to PO against 28.4% for PiS this year. In Kraków, PO won 37.8% against 25.7% for PiS. In all three cases, these dots of orange on the map stand out from their very conservative surroundings. Lublin and Białystok, however, both went to PiS with margins over 10%. PO won some of its best results nationally in the cities of Gdánsk (54.2%), Gdynia (53.5%), Chorzów (50.8%), Opole (50.4%), Katowice (48.8%), Poznań (44.5%), Wrocław (42.9%) and Szczecin (42.7%).

One major exception to the east-west rule in the form of a ‘blue island’ in the formerly German west is the region around Polkowice, Głogów and Lubin counties in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, the heart of the Legnica-Lubin-Głogów copper mining district, home to a major (but struggling) copper mining industry.

Portugal

Turnout: 33.84% (-2.93%)

MEPs: 21 (-1)

Electoral system: Closed-list PR (d’Hondt), no threshold (national constituency)

PS (S&D) 31.46% (+4.88%) winning 8 seats (+1)

Aliança Portugal PSD/CDS-PP (EPP) 27.71% (-12.37%) winning 7 seats (-3)

PCP-PEV (GUE/NGL) 12.68% (+2.02%) winning 3 seats (+1)

MPT (ALDE) 7.14% (+6.48%) winning 2 seats (+2)

BE (GUE/NGL) 4.56% (-6.17%) winning 1 seat (-2)

Livre (G-EFA) 2.18% (+2.18%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PAN 1.72% (+1.72%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PCTP/MRPP 1.66% (+0.45%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PND 0.7% (+0.7%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PTP 0.69% (+0.69%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PPM 0.54% (+0.15%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PNR 0.46% (+0.09%) winning 0 seats (nc)

MAS 0.38% (+0.38%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Pro-Vida 0.37% (+0.37%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PDA 0.16% (+0.16%) winning 0 seats (nc)

POUS 0.11% (-0.03%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Portugal has been hit hard by the economic crisis – it was one of the so-called ‘PIGS’/’PIIGS’ countries along with Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain (and now Cyprus) and it received a bailout from the ‘Troika’. However, unlike in Greece, Spain or Italy, the economic and social crisis in Portugal has not triggered major changes in the Portuguese political or party system.

Since the Carnation Revolution in 1974, which overthrew the Estado Novo dictatorship (1933-1974), Portuguese governments usually ran deficits above and beyond the EU’s 3% deficit limit – in 2009, Portugal’s deficit was 10.2% of GDP and 9.8% of GDP in 2010 – and the size of the public sector grew exponentially (the number of public servants increased from 372,000 in 1979 to a peak of 663,100 in 2010, surpassing the average number of public servants per inhabitant in the rest of the EU). Furthermore, Portugal – which was the EU’s poorest member-state prior to the 2004 enlargement (and has since fallen even further behind) suffered from sluggish economic growth in the years leading up to the global recession and Eurozone debt crisis. For example, in 2005 and 2006, the Portuguese economy grew by only 0.8% and 1.4% (because of competition from China and Asia for the traditional textile and footwear industries) while the EU-27 grew at rates of 2.2% and 3.4% in those pre-crisis years. Portugal also had very high levels of household debt. Despite all that, governments spent quite lavishly on public works projects, bonuses and wages for public sector and parastatal bosses and mismanaged EU funds. In 2009, Portugal’s GDP fell by 2.9% and the government was forced to bailout and nationalize two major banks – the Banco Português de Negócios and Banco Privado Português – who had been accumulating loses due to bad investments, embezzlement and accounting fraud. The BPN’s president, who had close ties to several politicians including President (and former Prime Minister) Aníbal Cavaco Silva, was later arrested for suspected tax fraud, money laundering and forgery.

The Socialist Party (PS), led by moderate Prime Minister José Sócrates, was the incumbent government when the Eurozone debt crisis hit Portugal beginning in 2010. Sócrates’ PS had been elected in a landslide (winning an absolute majority by itself) in 2005, on the heels of the unpopular governments of Prime Ministers José Manuel Barroso (2002-2004) and Pedro Santana Lopes (2004-2005). Sócrates’ government was accused by the centre-right opposition of having failed to anticipate the economic crisis when he took office in 2005 and general economic mismanagement. Pressured by financial markets and the EU, the Sócrates government passed three successive austerity packages in 2004 which included tax increases, pay cuts for public servants and spending cuts. These policies did little to alleviate the crisis, as Portugal’s credit rating was downgraded and risk premiums on Portuguese bonds reached record highs. Nevertheless, the Sócrates government resisted pressure to seek European help. In the spring of 2011, Portugal was left with little option but to seek a EU bailout. However, in March 2011, the opposition parties on the left and right – which held a majority in the National Assembly – joined to reject a fourth austerity package put forward by the PS minority government and Sócrates resigned, prompting early elections in June 2011. As a caretaker Prime Minister, Sócrates finally admitted the need for a €78 billion Troika bailout.

The main party of the Portuguese centre-right is the misnamed Social Democratic Party (PSD). Portugal has an acute case of sinistrisme, where what passes as the right elsewhere in Europe shies away from adopting labels such as ‘right’, ‘conservative’ or even ‘liberal’ due to the association with the Estado Novo dictatorship in general and Salazar’s regime in particular. The PSD’s name also reflects the party’s origins and mythical founding leader, Francisco Sá Carneiro (died in 1980), a ‘Portuguese social democrat’ who developed a moderate, anti-collectivist and anti-statist form of social democracy adapted to the Portuguese context, influenced both by Catholic social teachings (humanism and Emmanuel Mounier’s personalism) and German social democracy. The PSD even applied to join the Socialist International. However, after Sá Carneiro’s death in 1980, the PSD clearly shifted to the mainstream European right (although the PSD would deny it) under Prime Ministers Aníbal Cavaco Silva (1985-1995) and José Manuel Barroso (2002-2005), who both implemented liberal economic policies. The PSD originally joined the liberal family in the EP, before leaving it for the Christian democratic EPP family in 1996. The PSD’s traditional junior ally, the People’s Party (CDS-PP), identifies with ‘centrism’ (the party’s original name – CDS – stood for ‘Social and Democratic Centre’) but lies further to the PSD’s right – socially conservative, softly Eurosceptic, mildly nationalistic and somewhat populist. The PS, PSD and CDS-PP are ideologically similar, moderate parties which have governed from the centre and found common cause in opposing the left-wing revolutionary movement in the chaotic transition years of 1974-1976 (the Processo Revolucionário em Curso, PREC), which was spearheaded by the Communist Party (PCP) and left-wing sectors in the military.

The PSD seized on anti-incumbency and the unpopularity of the PS government associated with the economic collapse to win the 2011 elections, with Pedro Passos Coelho’s PSD ultimately defeating Sócrates by an unexpectedly comfortable 10.6% margin (38.6% to 28.1%). Polls had indicated a much closer contest, but the PS ended up badly underperforming its polling. Pedro Passos Coelho, in contrast with the right-wing opposition parties in Spain and Greece, ran a brutally honest pro-austerity (and pro-bailout) campaign – most notably, Passos Coelho said that he would go beyond what the EU-IMF were asking from Lisbon, determined to make Portugal stand out (from Greece, notably) as the ‘good pupil’ of austerity in southern Europe. The PSD formed a coalition with Paulo Portas’ CDS-PP.

Portugal received a €78-billion bailout from the ‘Troika’, in return for austerity measures and structural reforms. Passos Coelho set out to go further and be even more ambitious than what the Troika asked, to meet the EU-IMF’s demands ahead of schedule and to complete the bailout program within the planned timeframe. The PSD’s platform in 2011 was unusually right-wing and neoliberal for a traditionally left-of-centre country like Portugal, including proposals for constitutional reforms which would allow private sector participation in healthcare, education, social security and the privatization of water and postal services. The government quickly set out to introduce tough austerity measures including: spending cuts (notably in education and healthcare); income and corporate tax increases; abolishing the ’13th and 14th month’ bonuses (for Christmas and July) for public servants; a continued pay freeze for public servants (and a fall in real wages from 2010); privatizations; halting public work projects (notably a high-speed railway); selling the state’s golden shares in the electricity, telecommunications and energy companies; significant hikes in electricity prices due to a major increase on the VAT on energy (from 6% to the standard rate of 23%); reduction of the public sector payroll through attrition; public transit fare increases; an increase in working hours (30 minutes per day, unpaid); devolution of powers to local governments but cuts in fiscal transfers to these same local governments and the elimination of four public holidays. Passos Coelho originally claimed that even deeper austerity was necessary because his government had discovered a €2 billion ‘hole’ in the budget left behind by the PS, but the opposition parties claimed that it was only an excuse for deeper cuts.

These austerity policies had little success in creating economic growth or even reducing the deficit. In 2011, it was revealed that the autonomous region of Madeira – the personal preserve of PSD baron Alberto João Jardim since 1978 – had been under-reporting its public debt since 2008, hiding a total of €1.218 billion in debt between 2008 and 2010, while the regional government had a total debt of €6.328 billion. Despite the scandal, Alberto João Jardim was reelected to a ninth full term in office with yet another absolute majority in October 2011, although the PSD’s support fell by 15.7%. The deficit was brought down to 4.3% of GDP in 2011 but increased again to 6.4% in 2012, before falling to 4.9% in 2013 (but, in 2011, the original Troika demand had been pushing for a 3% deficit in 2013). Portugal has been in recession since 2011, with -1.3% in 2011, -3.2% in 2012 and -1.4% in 2013. The government’s forecasts had initially predicted positive growth in 2013, but current estimates show that the economy might finally grow again only this year (+1.2% predicted by the EC). The government had more trouble than it had expected because its austerity policies in 2011 and 2012 led to a major collapse in consumer spending, and lower than expected revenues for the state. Furthermore, despite the austerity, Portugal’s bond yields remained high and refused to budge for most of 2012 (in contrast to Ireland or Spain) and Portugal’s credit rating was again downgraded – the country currently has a negative outlook BB rating from Standard & Poor’s.

The unemployment rate soared from 12.6% when the PSD took office in June 2011 to a high of 17.4% in early 2013, although it has since begun declining to stand at 14.3% in May 2014. In September 2012, ostensibly to reduce unemployment, Passos Coelho announced cuts in the social security paid by employers (from 23.25% to 18%) – financed by a concomitant increase in social security contributions from employees (from 11% to 18%), which meant a clear fall in employees’ take-home pay. The Prime Minister’s policy unleashed a firestorm of criticism – it united the radical left, trade unions and the PS against the government, and was criticized on the right by a former PSD leader (Manuela Ferreira Leite) while Paulo Portas, the leader of the CDS-PP and foreign minister, indicated his disagreement with the idea and raised the specter of a coalition crisis between the PSD and its junior partner. In late September, after a very successful strike and protest movement against the government, it was finally forced to scrap the idea of toying around with social security contributions. But forced to meet the Troika’s demands, the government chose to raise taxes. Even after the decision, the CDS-PP continued to show its thinly-veiled displeasure with the government, although the government’s junior member still voted in favour of the budget in October 2012.

However, in January 2013, President Aníbal Cavaco Silva – a member of the PSD, but who has often acted as he saw fit while President (an unconventional and often interventionist style which has won him many critics and low approval ratings for a Portuguese head of state) – announced that he would take several items from the 2013 budget to the Constitutional Court for a decision on their constitutionality. In April 2013, the court ruled that three items from the budget were unconstitutional: abolishing the ’13th and 14th month’ bonuses for public servants (on the grounds of not respecting equality between public and private employees), abolishing the ’13th and 14th month’ bonuses for retirees and a special tax on unemployment and sickness benefits. It upheld, however, a ‘solidarity tax’ on pensions over €1,350 a month. The court (who declared its ruling to be retroactive) blew a €1.3 billion ‘hole’ in the budget. The government was livid and its attacks on the court’s ruling were unexpectedly violent – accusing it of placing the country’s stability in jeopardy and fueling rumours that Portugal would need a second bailout. Yet, forced to conform, Passos Coelho announced that spending cuts would replace tax hikes in 2013. The court has continued to reject austerity measures proposed by the government, heightening tensions between the government and the judiciary. The government would like to open the constitution to amend clauses and allow for more spending cuts and a reorganization of state-provided health services and public education, as the IMF has proposed, but the PS has refused to discuss such reforms.

In July 2013, the government faced another crisis – this time within its own ranks. It began with the resignation of Vítor Gaspar, the technocrat finance minister (embattled by the failure of austerity policies which failed to meet targets), and his replacement by María Luis Albuquerque, from the PSD. Paulo Portas, the leader of the CDS-PP and foreign minister, handed his resignation to the Prime Minister – and said it was ‘irreversible’. However, Passos Coelho refused to accept his resignation and created a political crisis with an uncertain resolution – Passos Coelho tried to mediate the crisis internally by promoting Paulo Portas to Deputy Prime Minister (a new title) while the President reiterated his old demand for a ‘national salvation’ government with the PS and snap elections in 2014 after the bailout program’s conclusion. The PS quickly shut the door on any ‘national salvation’ coalition, and Cavaco Silva was forced to accept the reshuffled coalition cabinet with Portas now sitting as Deputy Prime Minister.

Portugal’s economic health has only just begun improving. The economy should grow in 2014, for the first time since 2010; bond yields have fallen; unemployment should keep falling; the debt has peaked at 129% of GDP and should begin decreasing and Lisbon is projected to finally meet the EU’s 3% deficit limit in 2013. Part of the growth has come thanks to exports, as the country now boasts a current account surplus. The country managed to successfully exit the Troika bailout program on schedule in May 2014, without a safety net line of credit. The successful exit from the bailout program was a big victory for the government, which had repeatedly insisted that Portugal would complete its structural adjustment program within schedule. The EC praised the ‘efforts’ made by Lisbon but at the same time warned against complacency and underlined the need to continue pushing forward with structural reforms. The centre-right cabinet wishes to simplify rules to set up businesses, loosen a rigid labour market and lighten the burden on firms shackled by high charges from the protected non-traded sectors (utilities etc). The OECD says such measures could lead to a significant increase in the GDP by 2020.

However, the Portuguese mood remains overwhelmingly pessimistic and gloomy, with over 90% of respondents in the most recent Eurobarometer saying that the country’s economy is in bad shape (a level similar to Greece) and a significant number of Portuguese who are unconvinced that recovery is here for the long-term. The pessimism with regards to the economy has also been mixed with anger against the government and austerity. Since November 2011, the government has faced several strikes and large protest movements (of varying success), led by trade unions. The CGTP-IS, the largest trade union confederation and an ally of the Communist Party (PCP), has usually been the most inflexible of the unions and been on the frontlines of all anti-austerity and anti-government protests. However, the effectiveness of the unions has been weakened by divisions in the wider movement – for example, in early 2012, the more moderate UGT (linked to the PS), refused to join the CGTP-IS in another strike. Many workers also stayed away from picket lines, unwilling to lose a day’s pay in a bad economy. In contrast to Greece, where protests since 2010 have often been heated, all protests in Portugal have been well-disciplined and peaceful.

Unlike in Greece but also Italy, Spain and even Ireland, the economic crisis in Portugal has not seen major changes in the political system. In addition to pessimism and anti-government feelings, common to all ‘PIIGS’ countries, Portugal has also been hit by apathy and general resignation in the face of the crisis. Voters unhappy with the government has not turned to new parties (there really aren’t any), far-right populists (like in Spain, the far-right in Portugal is an irrelevant joke) or even minor parties – instead, they’ve reacted with run-of-the-mill anti-incumbency and supported either the PS or the Communists. The PS – quite unlike the Spanish Socialists – has recovered quite nicely from its 2011 defeat under the new leadership of António José Seguro. There is little enthusiasm for the PS – in fact, most know that a PS government would apply similar austerity policies anyway (the PS has opposed the current government’s austerity policies, harshly at times but more softly than the radical left at other times) – but the PS seems to benefit from anti-incumbency and the lack of strong alternatives on the left.

The PS won the local elections in September 2013 – although the PS’ vote share fell slightly (by about 1%) from 2009, the PS won 36.3% of the vote for the municipal executives and won 149 municipalities, a gain of 17. The PS easily held Lisbon with over 50.9% of the vote, and the PS gained cities including Coimbra, Vila Nova de Gaia, Sintra, Vila Real and the Madeiran capital of Funchal (an historic defeat for the PSD). On the other hand, the PS lost Braga and Guarda to the PSD and lost three major municipalities (Loures, Beja, Évora) to the Communists. An independent candidate backed by the CDS-PP gained Porto from a term-limited PSD mayor, winning about 39.3% against 22.7% for the PS and only 21.1% to the PS.

The PS won the EP elections with a fairly strong result (31.5%). However, the narrow margin of victory (3.8%) and the underperformance compared to polling (the PS was polling about 36-38% and predicted to win between 9 and 10 MEPs) in a context which should have been quite favourable to the opposition, makes it a very bitter victory indeed for the PS. With elections due in 2015, António José Seguro, the PS leader, may face a leadership challenge from António Costa, the popular PS mayor of Lisbon. That being said, the result can hardly be considered a victory for the centre-right governing parties, who ran a common list (like in the 2004 EP elections) known as Aliança Portugal. The two parties won only 27.7% of the vote, compared to 40.1% for the two parties running separately in the 2009 EP elections (a surprise victory for the PSD over the then-governing PS) and 50.4% in the 2011 election. The right’s result is so catastrophic that it is even lower than the result of the PSD alone in either 2011 (38.7%) or 2009 (31.7%), and the Aliança Portugal coalition also badly underperformed its polling (29-30%, predicted to win between 7 and 9 seats). The centre-right parties returned only 7 MEPs – 6 from the PSD and 1 from the CDS-PP – compared to 10 in 2009.

One of the main winners of the election was the Democratic Unitarian Coalition (CDU), the permanent coalition between the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and the Greens (PEV) – although the PCP is the dominant and only relevant party of the two, with the Greens more or less acting as the PCP’s section for environmental issues. The Communists remain fairly unreconstructed – the party’s logo still has the distinctive hammer and sickle and the PCP continues to issues communiqués praising communist regimes or denouncing ‘imperialism’ – although, in practice, the PCP largely offers fairly innocuous and standard-fare leftist populism around bread-and-butter issues (which makes the PCP more in touch with reality than the Greek Communists, who are completely in the 1950s). In the EP campaign, for example, the CDU called for a renegotiation of the debt, increasing national production, higher wages and pensions, higher taxes on capital gains and profits, defense of public services and defense of Portuguese national sovereignty against the EU and the Troika (held responsible for what it calls the ‘aggression pact’). The PCP The Communists have been on an upswing recently, having won their result since the late 1990s in the 2013 local elections (11%) and, with 12.7%, it has won its best result in an EP election since 1989. However, because of low turnout, the CDU’s result in terms of raw votes (416.4k votes) is lower than its 2011 intake (over 441 thousand votes, or 8%), so the result is likely one of differential turnout and the Communists’ ability to hold and turn out their loyal base. Nevertheless, the PCP did increase its raw vote in the 2013 local elections – both compared to the previous local elections in 2009 and 2011 – so the Communists have seen a real increase in support. However, their potential for growth is still fairly limited.

The Communists have retained a sizable and loyal electoral base since the Carnation Revolution, although it has seen its support decline somewhat from the 1970s and 1980s. The PCP’s electoral base is very regionalized – it retains very strong support, at all levels of government, in the Alentejo region and Lisbon’s industrial hinterland in the Setúbal Peninsula. In this election, the PCP was the largest party in the districts of Setúbal (29%) and Beja (35.3%) and placed a very strong and close second behind the PS in Évora (31.3%). In contrast, the Communists won less than 5% of the vote in the Azores, Madeira and northern districts such as Bragança and Viseu. Although Portugal is, politically and administratively, a heavily centralized state with only weak local governments, there is a real regional diversity in the country – politically, which reflects a social and economic diversity. The inland south, the Alentejo region (districts of Beja, Évora, Setúbal and Portalegre) – to the south of the Tagus river and to the north of coastal Algarve – was historically a poor region characterized by latifundios, big landowners, landless peasants, anti-clericalism and rural agitation. The Communists were well organized with landless peasants, and the party played a major role in the land seizures and aborted agrarian reform which immediately followed the Carnation Revolution. The region, which remains quite poor and increasingly dominant on the public sector (especially in suburban Lisbon), is a left-wing stronghold in which the PSD regularly places a poor third. Northern Portugal was historically a region of smallholders, small and dispersed private property and often depicted as being very Catholic. Catholic smallholders violently resisted communist collectivization and agrarian reform during the Carnation Revolution/PREC. The north has usually leaned to the PSD, but it is far from being politically homogeneous: the PS has significant support, notably in the cities – Porto, an old republican and liberal bastion and the north’s major industrial centre, but also Braga and Coimbra.

The other winner of this election – a surprise winner – was the Party of the Earth (MPT), a small centre-right green party (it is part of a rump, right-leaning green international in which the German/Bavarian ÖDP and the French MEI are the only other relevant members) founded in 1993 which has regularly participated in all elections but has never really achieved much success – in the 2009 EP elections, running as the Portuguese ally of Declan Ganley’s Libertas, the MPT won only 0.66% and in 2011 the MPT took 0.41%. Its sole parliamentarian was a regional deputy in Madeira, reelected in 2011, with 1.9% of the vote. Its success in the EP elections, with a exceptional 7.1% and nearly 235,000 votes, was totally unexpected. Nobody had predicted that the MPT would win one seat, let alone two. The MPT’s success likely owes to two factors: its top candidate and its populist, anti-establishment platform. The MPT’s top candidate on its list was Marinho Pinto, a fairly well-known Portuguese lawyer and former president of the Portuguese Bar Association, who has often attracted media attention because of his controversial statements (he famously said that Brazil’s main export to Portugal were prostitutes and he has ranted about the ‘gay lobby’ in the past). The MPT had a populist and anti-establishment platform – although a lot of the platform is mostly feel-good, touchy-feely white noise, the MPT called for a renewal of the political elite, criticized EU technocrats and their illegitimacy and attacked financial deregulation all while still being fairly pro-EU. The party’s vote distribution was fairly homogeneous – it polled quite well in Madeira and coastal districts on the mainland (Porto, Aveiro, Coimbra, Viana do Castelo), but its vote did not have any major peaks or troughs. Unlike the German ÖDP, which joined the G-EFA group, the MPT’s two new MEPs have joined the ALDE group.

A major loser was the Left Bloc (BE), a radical left party which often compares itself to Greece’s SYRIZA, and like the Greek party it was originally founded as an alliance of various hard-left movements and minor parties (Maoists, Trotskyists, anti-globalization activists, New Left, Marxists). Usually focused on social issues such as non-discrimination, abortion, same-sex marriage (both of which are now legalized and have largely dropped off the political radar), the BE quickly gained ground in the early 2000s as a hip, trendy and modern radical left party – peaking at 10.7% in the 2009 EP elections (or 9.8% in that year’s legislative elections), and surpassing the Communists. Since that high water mark, however, the BE’s support has declined as the party’s niche issues have become far less relevant and the party’s profile and credibility on economic issues is both weaker and less distinctive from the other parties (often seen as lacking ideas of its own). Quite unlike its Greek friends, the BE has been unable to benefit from the economic crisis. In the 2011 election, the BE’s support fell back to 5.2% and the party lost half of its seats. Since then, the BE’s support in polls has jumped around a bit, but it has not really made new inroads. The retirement of the BE’s longtime leader and MP (since 1999) Francisco Louçã in November 2012 and his replacement by two rather anonymous coordinators hasn’t helped. The BE also faces serious infighting. In 2011, MEP Rui Tavares defected and joined the G-EFA group in the EP, and went on to found Livre, an eco-socialist party. Other members of the BE has pressed, unsuccessfully, for the party to become a potential left-wing governing partner for the PS. On economic issues, at the forefront nowadays, the BE has trouble distinguishing itself from the PCP – it favours an audit and renegotiation of the debt, higher incomes, nationalization of bailed-out banks and rejects the Fiscal Compact – it only really breaks from the PCP in being pro-European and calling for a broad leftist government. However, the BE lacks the PCP’s advantages – the Communists have a loyal electorate, strong trade union roots and an old grassroots presence in the Alentejo and other regions. Livre, running independently with Rui Tavares, won 2.2% of the vote – a result which would allow it to win at least one seat in a legislative election.

Some small parties below the threshold did quite well too. The Party for Animals and Nature (PAN), an animal rights’ party which elected its first regional deputy in Madeira in 2011, won 1.7% nationally and 3.3% in Madeira. The Portuguese Labour Party (PTP), the fourth largest party in the regional parliament in Madeira now led by José Manuel Coelho, a populist and loudmouth critic of PSD boss Alberto João Jardim, won 6.6% and fourth place in Madeira. Nationally, the Portuguese Workers’ Communist Party (PCTP/MRPP), an old Maoist party (of which José Manuel Barroso was a member, before being expelled) last famous during the Carnation Revolution in 1974-5 for being an inflexible enemy of the PCP (a ‘social-fascist’ fraud funded by the CIA, it claimed), won 1.7%. The PCTP amusingly seems to be doing better than ever before, on the heels of a record high performance of 1.1% in 2011.

Political apathy bred by the crisis also expressed itself in the form of the lowest ever turnout in a Portuguese EP election – only 33.8% of voters turned out on May 25, compared to 36.8% in 2009. There was also a high number of white and invalid votes: 4.41% and 3.06%, compared to 4.63% and 2% in 2009.

Romania

Turnout: 32.44% (+4.77%)

MEPs: 32 (-1)

Electoral system: Closed-list PR, 5% threshold for parties only – doesn’t apply to independents (national constituency)

PSD-PC-UNPR (S&D) 37.6% (+6.53%) winning 16 seats (+5)

PNL (ALDE>EPP) 15% (+0.48%) winning 6 seats (+1)

PDL (EPP) 12.23% (-17.48%) winning 5 seats (-5)

Independent – Mircea Diaconu (ALDE) 6.81% (+6.81%) winning 1 seat (+1)

UDMR (EPP) 6.29% (-2.63%) winning 2 seats (-1)

PMP (EPP) 6.21% (+6.21%) winning 2 seats (+2)

PP-DD 3.67% (+3.67%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PRM (NI) 2.7% (-5.95%) winning 0 seats (-3)

Forța Civică (EPP) 2.6% (+2.2%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PER (G-EFA) 1.15% (+1.15%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Others 5.63% (-1.07%) winning 0 seats (-1)

Romania is, after neighboring Bulgaria, the second poorest member-state in the EU and also one of its newest members, having joined the Union with Bulgaria in 2007. Romanian politics in the past few years have been marked by growing apathy and dissatisfaction with the political system, as seen by the declining turnout in national elections (41.8% in the 2012 legislative election, which was actually up from 39.2% in 2008!). Politics in Romania are far more personal than ideological – although there are parties, who have somewhat coherent ideologies and do line up with European ideologies, the political debate is often largely around personality rather than ideological issues. As such, politics have tended be quite bitter and acrimonious, and it has become increasingly so under President Traian Băsescu, who leaves office later this year after ten years as Romania’s head of state. Parties have little ideological differences, and should perhaps be understood as patronage machines or personal vehicles; in contrast with other post-communist countries, however, Romania has not really seen the rapid rise and subsequent collapse of new parties. Partisan loyalty has been increasingly thin, with an increasing number of politicians who have switched parties. The parties themselves have switched alliances repeatedly in the past years, making coalitions tenuous and governments increasingly unstable. Romania suffers from a toxic conflation of political and business elites, and the media – when it is not owned outright by politicians – is intensely partisan.

The Romanian Revolution in 1989, which overthrew Nicolae Ceaușescu’s brutal and ‘Sultanistic’ communist regime, is increasingly seen as an ‘internal coup’ in which second-tier Communist apparatchiks, such as President Ion Iliescu (1990-1996, 2000-2004), quickly moved in and seized power for themselves, replacing Ceaușescu’s personal clique with a new elite. This new elite proved to be corrupt, unwilling to engage in deep reform and autocratic – in power, it was predominantly concerned with shoring up its own power and settling scores with political opponents and the opposition parties. Since then, Romanian politicians and governments have often been more interested by personal vendettas against their opponents than dealing with issues such as corruption and economic reform. The National Salvation Front (FSN), the provisional government which replaced Ceaușescu and which was largely staffed by formerly sidelined Communist apparatchiks (like Iliescu) or second-tier regime and the ubiquitous secret police (Securitate), did not hold together for long and various factions alongside warring political bosses soon went their own ways. Iliescu’s faction, more allergic to reforms, eventually became the Social Democratic Party (PSD), a rather powerful collection of former communist officials, Securitate assets and corrupt local political barons. Although Iliescu’s administrations were largely marred by corruption and sluggish reforms, the PSD has become more reformist under recent leaders – critics would contend that the reforms were deceitful, aimed at tricking the EU into accepting Romania and putting up an outward appearance of change while a corrupt and autocratic elite blocked real change. The slightly more reformist and liberal faction of the FSN founded the Democratic Party (PD) in 1993, which merged with dissidents from the National Liberal Party (PNL) to become the Democratic Liberal Party (PDL).

In 2004, Traian Băsescu, a former ship captain and PD mayor of Bucharest, was narrowly elected President in alliance with the PNL, a centre-right liberal party (based on the powerful interwar party) supportive of economic reforms and neoliberal policies (such as the flat tax). Under the agreement, the PNL’s Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu became Prime Minister in coalition with the PD, the Hungarian minority party (the UDMR) and the small ‘Humanist Party’ (now the Conservative Party, PC). Băsescu, a right-leaning populist known for his hot temper and abrasive bully personality, was elected on an anti-corruption, anti-elitist and anti-communist platform. He has often lashed out at his political opponents and media critics in foul-mouthed tirades, or making offensive statements. His political opponents have repeatedly accused him of breaking or bending the constitution, and – like his predecessors – has often used his office to settle scores or wage war on his opponents. Băsescu utterly failed to live up to his promises – going after corruption in Romania is often a one-sided affair, mostly motivated by partisan ends, and Băsescu’s opponents claim that he has only used the presidency to replace an old guard with his cronies.

Given his hot temper, it is no surprise that relations between Băsescu and his first Prime Minister quickly broke down beginning in 2005-6 and culminated with Popescu-Tăriceanu dismissing all PDL ministers from his cabinet in April 2007, forming a minority government with the UDMR and PC which received support from the opposition PSD. Under the Romanian constitution, the President appoints but may not dismiss the Prime Minister, much to Băsescu’s chagrin. His opponents in Parliament voted to impeach him on fairly flimsy grounds in April 2007, but Băsescu survived the impeachment referendum in May 2007 – turnout was under 50% and thus invalid anyhow, and those who did vote opposed his impeachment with three-quarters against. In 2008, the PDL and PSD emerged from legislative elections as the two largest parties, with the PNL trailing in third. Băsescu successfully blocked the formation of an opposition PSD-PNL cabinet, and instead appointed a PDL-PSD coalition led by Emil Boc, the PDL mayor of Cluj-Napoca. However, relations between the two warring partners worsened with the very heated 2009 presidential election (in October 2009, the PSD joined the opposition parties in voting a no-confidence motion in Boc’s government), in which Băsescu faced a very difficult challenge from the PSD’s Mircea Geoană in the second round. The PNL’s first round candidate, Crin Antonescu, endorsed Geoană in the runoff. Băsescu was reelected in an extremely narrow election, with 50.33% of the vote and a 70,000 vote majority; the PSD cried wolf, but the Constitutional Court dismissed the PSD’s claims of vote rigging. Băsescu was returned to office, but the election had pushed the PSD and PNL even further away from him, creating a highly-charged and polarized political climate.

Băsescu’s Prime Minister, Emil Boc, now governing with the UDMR and opportunistic pro-Băsescu PSD-PNL dissidents, also needed to deal with a poor economy (-6.6% recession in 2009, -1.1% recession in 2010) and a large budget deficit (9% in 2009, 6.8% in 2010, 5.5% in 2011). The government received a €20.6 billion loan in 2009 from the IMF, in exchange for stringent austerity policies. Public sector wages were cut, spending was cut, the VAT was increased and social benefits were cut. These austerity policies brought a strong reaction from Romanians, who were tired of low wages and tax increases while politicians continued to line their pockets. They took to the streets in early 2012, initially to protest a health reform which would have cut benefits and privatized a good deal of the healthcare sector, but the protests later became a broad anti-government movement. They successfully obtained the resignation of Emil Boc in February 2012, who was replaced by Mihai Răzvan Ungureanu, a former boss of the foreign intelligence services, who tried to form a coalition based around the same parties. In late April 2012, however, Ungureanu’s cabinet was toppled by a no-confidence motion supported by the opposition – the PSD, PNL and PC had formed an electoral coalition, the Social Liberal Union (USL) in February 2011.

Băsescu was forced to appoint Victor Ponta, his sworn enemy and leader of the PSD, as Prime Minister at the helm of a clearly anti-Băsescu USL cabinet. The new cohabitation between the two enemies of Romanian politics unleashed a major constitutional crisis, where both sides acted like elementary school kids in a schoolyard brawl. Victor Ponta was accused of plagiarizing his doctoral thesis – over 80 pages of his thesis were plagiarized, lifting entire pages and arguments from other authors. Ponta – who dismissed the commission in charge of academic integrity and refused to resign – claimed that Băsescu’s allies had leaked the plagiarism scandal to the press to sully him, and reacted by leaking details of corruption allegations surrounding Băsescu. Matters got even worse when, at around the same time, Ponta’s doctoral thesis advisor and political mentor, former PSD Prime Minister Adrian Năstase (2000-2004, defeated by Băsescu in 2004), was found guilty of corruption and sentenced to two years in jail (and tried to commit suicide when the police came to escort him to jail).

In June 2012, the Constitutional Court ruled against Ponta in a dispute between him and Băsescu over who from Ponta and Băsescu should have represented the country at a European summit. In reaction to this judicial rebuke, Ponta went all-out against the judicial system, claiming that the courts were stacked with Băsescu loyalists. The government threatened to fire Constitutional Court judges, fired and replaced the ombudsman with a party loyalist, seized control of the official journal, replaced the heads of both chambers of Parliament and tried to remove the Constitutional Court’s ability to rule on parliamentary matters. Ponta’s attack on judicial independence and his autocratic behaviour were badly received by the EC and EU leaders, and many began painting Ponta as Romania’s own Viktor Orbán. The EC issued a stark warning to the Romanian government in early July, and Angela Merkel minced no words in condemning Ponta’s actions. The EC has debated which sanctions, if any, should be adopted against Romania. A freeze in EU transfers was seriously considered, but the crisis derailed or at least significantly delayed Romanian attempts to join the Schengen area. Unlike Orbán however, Ponta has not been defiant of European institutions and moved to soothe fears that he was staging something akin to a coup d’état. Ponta claimed that there had been misunderstandings, and reassured that he would withdraw his controversial laws if they were to cause any trouble for Romania in the EU. The PSD’s allies in the S&D group in the EP lined up to defend Ponta, criticizing the EPP and the European centre-right governments of being biased against Ponta and unfairly attacking him, while pointing out that the EPP was far less vocal in attacking Orbán’s actions in Hungary (likely because Orbán’s Fidesz is a member of the EPP).