Monthly Archives: October 2013

Luxembourg 2013

Legislative elections were held in Luxembourg on October 20, 2013. All 60 seats in the Chamber of Deputies (D’Chamber or Chambre des Députés), elected by proportional representation in multi-member constituencies to serve five year terms (unless it is dissolved earlier, like this year).

The country is divided into four multi-member constituencies, each including two or more cantons and returning a variable number of deputies: Centre (21), Est (7), Nord (9) and Sud (23). Voters have as many votes as they are seats; they may choose to cast a single vote for a party list (and number additional candidates if the party’s list has less candidates than there are seats) or he/she may vote for individual candidates on one or more lists and give candidates up to two votes until he/she ‘runs out’ of votes. Seats are distributed proportionally to each party in the constituencies based on the total numbers of votes (list/candidate) each list received. The original allocation of seats is done using the Hagenbach-Bischoff method, with unfilled seats allocated according to the highest averages method.

Background

Luxembourg, a small constitutional monarchy sandwiched between Belgium, Germany and France, is one of the world’s wealthiest countries and – unsurprisingly – has been a haven of remarkable political stability since 1919, only interrupted by the Second World War. At the core of this political stability is the hegemony of the country’s “natural governing party”, the Christian Social People’s Party (Chrëschtlech Sozial Vollekspartei, CSV). The CSV, founded in 1944, and prior to that its pre-war incarnation – the Party of the Right (PD) – has been the largest party in the Chamber in every election since 1919, the first ‘modern’ election with universal suffrage, proportional representation and a party system. The constitutional reforms of 1919 introducing universal suffrage marked the end of a political era dominated by a small clique of liberal-minded elites, replacing it with a modern party system.

The CSV or the PD have formed government (providing the Prime Minister) since 1919 with the exception of 1925-1926 and 1974-1979. However, to consider Luxembourg a “one-party dominant” system because of the Catholic right’s dominance is probably erroneous: they have consistently governed in coalition with other major parties, either the liberals or the socialists, since the war and the PD formed a single-party government only once, between 1921 and 1925 (when it held an absolute majority). As in Austria, there is a strong tradition of ‘Grand Coalition’-type governments in the country, although unlike in Austria this tradition predates 1945.

Ideologically, the CSV is a moderate, centre-right and very much pro-European Christian democratic party. On economic and social matters, the Catholic right has long been influenced by Christian social teachings and PD/CSV-led governments laid the bases of the country’s social security and welfare state systems beginning in the 1920s and continuing in the post-war years.

Luxembourg, despite its small size, has played an active role in European politics since the war. The country has long played a strategic role in European power politics and has always been closely tied to its neighbors. Until the First World War, Luxembourg maintained extremely close economic ties with Germany, who controlled a significant share of the country’s nascent industry and infrastructure. In the 1920s, Luxembourg formed an economic union with Belgium.

After the Second World War, Luxembourg gradually became one of the more influential powers in European diplomacy, despite its small size and population. The country was a founding member of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), a major step given that the creation of the ECSC placed steel – the main resource of the Grand Duchy – under supranational control. It was a founding member of the EEC and Euratom in 1957. Given the country’s small size, its leaders have been keen to promote their country’s interests and ensure their representation in supranational institutions, so that larger domineering powers did not come to overwhelm smaller member states such as Luxembourg. It has been remarkably successful in doing so; Luxembourg has gained a reputation as a trustworthy intermediaries in European negotiations and it is home to a number of EU institutions. Luxembourg, alongside Scandinavia, spends the most (as a % of its GDP) on international development aid, about 1% of the country’s GDP.

Luxembourgian politicians have also been at the forefront of EU politics. CSV Prime Minister Pierre Werner (1954-1974, 1979-1984) is considered the forefather of the Euro; two former Prime Ministers, including the CSV’s Jacques Santer (1984-1995) was President of the European Commission between 1995 and 1999. Liberal Prime Minister Gaston Thorn (1974-1979) had held this office between 1981 and 1985. Incumbent CSV Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker, has played a major role on the European scene, as a former president of the Eurogroup and has championed greater social integration in the EU.

The CSV remains strongly pro-European. Unlike German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU, the CSV supports Eurobonds and its 2013 platform talks of the need for ‘solidarity’ by wealthier member states, the need for structural reforms aimed at economic growth and minimum basic rights for European workers and criticized the United Kingdom’s attempts to “empty EU policies of their substance”.

Jean-Claude Juncker (CSV) has served as Prime Minister since 1995, which makes him the longest-serving head of government in EU and one of the longest-serving in the world as a whole (and, arguably, the longest-serving democratically-elected head of government in the world). Juncker was forced to resign and call for snap elections, a year ahead of schedule, in July 2013 after a scandal in the State Intelligence Service (SREL).

An investigation revealed that the SREL had engaged in irregular and illegal activities including illegal wiretaps, bugging politicians, extrajudicial operations and maintaining files on citizens and politicians. In November 2012, the media published details of a conversation between Juncker and the former director of the SREL which had taken place in 2007. The former director mentioned the existence of 300,000 individual files on citizens and politicians and even alleged links between Grand Duke Henri and the MI6. Juncker, as the person responsible for the SREL’s actions, was accused of failing to notice and report on illegal activities and deficiencies within the SREL. In July 2013, the CSV’s coalition partner, the social democrats (LSAP) withdrew their support and tabled a motion of no confidence. Juncker resigned and asked the Grand Duke to dissolve parliament before the motion could be voted on.

The CSV’s campaign emphasized the government’s record on fields such as family policy, pension reform, healthcare, wages (the minimum wage was increased in 2011 and 2013) and fiscal policy (reducing the deficit, which is less than 1% of GDP; the party wants to balance the budget by 2017). Its other priorities included increasing benefits for low-income individuals, a more active social housing policy, investments in post-secondary education and R&D, primary education in French and reducing youth unemployment by pushing the youths to ‘assume responsibility’ and compel them to accept job offers (even below their skill levels). Another of the CSV’s main objectives in this campaign was a major proposal to reduce the number of communes in the country by organizing a national referendum on the subject in 2017, and reviewing the division of responsibilities between the levels of government.

The CSV has a strong Catholic tradition and still favours a strong role for the Church in public life and religious classes in schools, but it is no longer conservative on moral/societal questions: the party supports same-sex marriage and voted in favour of legalizing euthanasia in 2008.

The Luxembourg Socialist Workers’ Party (Lëtzebuerger Sozialistesch Aarbechterpartei, LSAP) has almost always been Luxembourg’s second strongest party, behind the PD/CSV. The country’s socialist party was founded in 1905 and refounded as the LSAP, on the model of Britain’s Labour Party, in 1945. The party has always been moderate and pragmatic: it formed an anti-clerical alliance with the liberals in 1908, and it has almost always been represented in government since 1937. The LSAP found itself outside the governing coalition only a handful of times since 1945: between 1969 and 1974, between 1979 and 1984 and between 1999 and 2004. It has governed in coalition with Juncker’s CSV since 2004, with LSAP leader Jean Asselborn as Deputy Prime Minister and foreign minister.

The LSAP, which won in the mid-to-high 30s in the 1950s and 1960s, has seen its support declined gradually, winning only 21.6% of the vote in the last election in 2009. The party’s support is very much concentrated in the Sud constituency, which covers the Red Lands region – the heart of the country’s old iron ore and steel industry.

The LSAP’s top candidate in this election was Étienne Schneider. Although the CSV accused the LSAP of treason for withdrawing their support from the government, the LSAP downplayed and denied such claims, blaming Juncker’s behaviour for his own downfall and the snap elections. Besides, the party’s campaign focused on other issues, notably economic or political issues. The LSAP took credit for most of the government’s reforms and said it was the “driving force” in the coalition with the CSV, having spearheaded major reforms in secondary education, healthcare and pensions.

Its platform called for tax reform (a new 45% income tax bracket for couples whose income is over €400,000 or singles whose income is over €200,000), lowering the voting age to 16, more referenda, separation of church and state, gender parity on electoral lists, primary education in French, capping rent increases and all-day schooling.

Above all, the question of ‘the index’ – the indexation of wages to the cost of living/inflation – was a major issue in this election. A recent reform means that the index will be modified only once a year (in October) until 2014, instead of twice a year before. The CSV supports capping the index and one increase per year (and removing tobacco, alcohol and oil from the calculation of the index); the LSAP took an offensive stance, claiming responsibility for the survival of the wage index, and proposing to return to the normal system of indexation once the crisis is over.

The Democratic Party (Demokratesch Partei, DP) is Luxembourg’s liberal party, which has traditionally placed third behind the CSV and LSAP. The DP was founded in 1955, a descendant of the Liberal League (founded in 1904, dissolved in 1925) and the post-war Patriotic and Democratic Group. The DP is not the CSV’s preferred coalition partners, so it has not been in government as often as the LSAP, but it was nevertheless in coalition with the CSV between 1959 and 1964, 1969 and 1974, 1979 and 1984 and 1999 and 2004.

Following the 1974 elections, in which the DP won a record high 22% of the vote, the DP’s Gaston Thorn formed a coalition with the LSAP, excluding the CSV – the only post-war government which excluded the CSV, to date. Thorn’s government coincided with the steel crisis of the 1970s, which badly hurt Luxembourg’s main secondary industry; but his government nevertheless passed a number of major societal reforms (abolishing the death penalty, no-fault divorce, abortion) and economic reforms which allowed for a less traumatic deindustrialization and transition to a tertiary (finance-driven) economy. However, the LSAP suffered loses in the 1979 election and the DP was unable to form another coalition with them, forcing them into a coalition under the CSV’s Pierre Werner until 1984. After major gains in the 1999 election (22%), the DP formed a government with the CSV’s Juncker.

The DP suffered significant loses in the last two elections, and won only 9 seats in the 2009 election and 15% of the vote, its lowest vote share since 1964. The DP is traditionally strong in urban and suburban areas, where it attracts middle-class and upper middle-class voters. As such, the DP often tailors its platform to the ‘middle-classes’.

The DP’s top candidate in this election was Xavier Bettel, the young (40) and openly gay mayor of Luxembourg City since 2011 (the DP has governed the country’s capital since 1970, it currently rules in coalition with the Greens).

The DP is the keenest supporter of liberal market economics in the country, although in practice it has been only moderately liberal and is probably to the left of the German FDP. The party’s catchphrase in this election was “spending less and offering more” – reviewing and rationalizing government spending, notably proposing to eliminate “gifts” made by the state. The DP used to support abolishing indexation, but it has backtracked on that unpopular decision. Instead, the liberals want to continue the current ‘extraordinary’ yearly indexation beyond 2014.

The party’s platform was strongly critical of the CSV-LSAP government’s record, particularly on fiscal matters. It decried the increase in the public debt (from 15% to 23% of GDP since 2009) and in unemployment (from 5.5% to 7%), saying that the country’s AAA credit rating could find itself threatened.

The Greens (Déi Gréng) were founded in 1983 as the Green Alternative Party, which won 2 seats in the 1984 election. The green movement split in 1985 and competed separately in the 1989 elections, before coming together to run a single list in the 1994 elections (10%). The Luxembourgian Greens are one of the consistently strongest green parties in Europe, winning 11.7% in 2009 and 16.8% in the European elections held alongside the 2009 legislative elections. The Greens have yet to participate in government nationally, but as aforementioned they are the DP’s junior partner at the local level in Luxembourg City – where they won over 18% of the vote in the 2011 local elections.

The Greens’ platform focused on traditional green issues (environment, energy etc) but also placed strong emphasis on ethics and democratic reform. The party proposed to create a two successive term limit for ministers, lowering the voting age to 16, voting rights for foreigners in legislative elections, greater governmental accountability to the legislature and a strong ethics charter for politicians and public officials. On other issues, the Greens’ proposals included separation of church of state, returning to the automatic indexation of salaries to inflation, promoting the Luxembourgish language and free public daycare.

The Alternative Democratic Reform Party (Alternativ Demokratesch Reformpartei, ADR) is a conservative party which finds its roots in a pensioners movement founded in 1987. The ADR was founded as a different names by activists who demanded the equality of state pensions between public servants and the general public (public servants earned 5/6th of their final salary as their pension, everyone else only had a basic state pension). This demand formed the core of the ADR’s platform until 1998, when a law was passed equalizing pensions. Afterwards, the ADR has sought to diversify its political agenda and has reincarnated itself as a conservative and Eurosceptic party, without losing its disproportionately elderly electorate or interest in pensioners’ issues. The ADR adopted its current name in 2006, dropping all references to pension reform from its name.

The ADR enjoyed early electoral success, winning 8% in 1989, 9% in 1994 and a record high of 11% in 1999. Its support has fallen back from that high water mark, to 8% in 2009.

The ADR is a conservative, populist and Eurosceptic parties. It opposed the 2005 European Constitution, which Luxembourgian voters approved in a referendum, and the Lisbon Treaty; the ADR stands out from other parties in the country, who, with the exception of the far-left, are all pro-EU. Its platform emphasized transparency, direct democracy (calling for more referenda), less bureaucracy and defense of the pension system. The party opposes any increase in the VAT, capping indexation and voting rights for foreigners.

The ADR campaigned rather heavily on the last issue, which is a major issue in a country where about 45% of the population are foreigners without Luxembourgian citizenship. A land of emigration when it was a poor, rural, agrarian backwater in the nineteenth century, Luxembourg has been a land of immigration since the 1890s with industrialization. Southern Luxembourg’s heavy industries attracted a large foreign workforce, notably from Italy or Portugal. Immigration increased during the 1960s and 1970s, a period of solid economic growth which coincided with a domestic labour shortage and a low fertility rate. The country welcomed a very large Portuguese population; Portuguese citizens make up about 16.4% of the country’s total population. The presence of major EU institutions in the country has also attracted a large foreign population working in EU institutions. Dual citizenship was allowed in 2009; residents having lived in the country for 7 years, passed an evaluation of Luxembourgish language skills and taken civic classes. The CSV and ADR both oppose extending voting rights for foreigners to in legislative elections (since 2003, all foreigners regardless of duration of residence and nationality may vote in local elections); the CSV supports reducing the residency requirement for citizenship from 7 to 5 years, something which the ADR also opposes.

The far-left is divided between The Left (Déi Lénk) and the Communist Party of Luxembourg (Kommunistesch Partei Lëtzebuerg, KPL). The former, which held one seat in the outgoing legislature, was founded in 1999 with the support of the KPL, LSAP dissidents and assorted leftists; it won 3% and 1 seat in the 1999 elections. However, the KPL split from The Left ahead of the 2004 election, which meant that The Left lost its seat while the KPL failed to gain a seat of its own. The Left regained its seat in 2009. The KPL was founded in 1921 by a split in the LSAP, and was fairly powerful electorally. It won over 10% of the vote in the first years after the war and in the mid-1960s, and lost its last seat in Parliament only in 1994.

The Left emphasizes redistribution of wealth by increasing the taxation of capital income, a more steeply progressive income tax and an increase in the minimum wage. The party’s platform also proposed reducing working hours, separation of church and state, a ‘social and regional’ Europe abolishing the monarchy. The KPL’s platform is broadly similar, emphasizing the defense of workers’ social rights. The KPL wants to nationalize major industries and some banks.

Two new parties appeared on the scene this year. The local Pirate Party (Piratepartei) is broadly similar to other Pirate parties in Europe, notably the German Pirates with which it has close ties. The party’s major themes include protection of personal data (including keeping banking secrecy, which is scheduled to be abolished), a basic income of 800€ per month, same-sex marriage, legalization of marijuana, abolition of mandatory voting, lowering the voting age to 16, granting foreigner residents the right to vote, and the promotion of Luxembourgish and its enshrinement in the constitution. The Pirates found themselves in hot water when they were forced to remove one of their candidates who had led a far-right party in the 1980s.

The Party for Integral Democracy (Partei fir Integral Demokratie, PIR) is another new party, founded by Jean Colombera, a ADR deputy who resigned from the party in 2012. Colombera, along with another ARD deputy who also left the party last year (Jacques-Yves Henckes) had criticized the ADR’s socially conservative and hard-right leadership; Colombera, a physician who practices homeopathic medicine, supports same-sex marriage and is under investigation for prescribing medical marijuana (he supports the legalization of cannabis). Colombera’s platform of platitudes is heavily influenced by holistic medicine. What can be drawn from the PID’s platform is that it is populist and anti-political; it supports direct democracy, some kind of Swiss consociationalism or Austrian Proporz (although it also seems to favour doing away with political parties) and has anti-bureaucracy rhetoric.

Results

Turnout was 91.15%, voting is mandatory in Luxembourg.

CSV 33.68% (-4.36%) winning 23 seats (-3)

LSAP 20.28% (-1.28%) winning 13 seats (nc)

DP 18.25% (+3.27%) winning 13 seats (+4)

Greens 10.13% (-1.58%) winning 6 seats (-1)

ADR 6.64% (-1.49%) winning 3 seats (-1)

The Left 4.94% (+1.65%) winning 2 seats (+1)

Pirates 2.94% (+2.94%) winning 0 seats (nc)

KPL 1.64% (+0.17%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PID 1.5% (+1.5%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Results by constituency

| CSV | LSAP | DP | Green | ADR | Left | Pirates | KPL | PID | |

| Sud | 32.24% | 28.17% | 12.74% | 9.78% | 7.52% | 5.73% | 3.03% | 2.4% | 1.35% |

| Centre | 35.31% | 14.65% | 25.02% | 10.46% | 5.01% | 4.75% | 2.72% | 0.86% | 1.22% |

| Est | 36.9% | 14.59% | 18.63% | 13.1% | 8.69% | 3.05% | 2.69% | 0.79% | 1.55% |

| Nord | 33.69% | 17.22% | 23.71% | 9.01% | 6.36% | 2.56% | 3.37% | 0.81% | 3.26% |

The CSV, as usual, polled (by far) the most votes although Prime Minister Juncker’s party suffered major loses. The CSV seems to have been hurt by the SREL scandal, which eroded the public’s trust not only in Juncker/the CSV but also in their politicians and institutions; but it was also hurt by the country’s weaker economy, with rising unemployment (7%), concerns about the affordability of public housing, social tensions over the indexation issue and the major growth in the country’s public debt. The LSAP, the CSV’s junior partner since 2004, also suffered smaller loses, reducing the party to a paltry 20.3%, its worst result in its history. The LSAP’s campaign, which consisted of criticizing the CSV while claiming credit for the achievements of the governing coalition since 2009, evidently had little popular appeal.

The main winner, meanwhile, was Xavier Bettel’s DP. The party likely benefited from its campaign, heavily critical of the CSV’s record in government, but it also benefited from its top candidate, Bettel, a popular mayor who received high ratings in leadership polls (although most voters preferred Juncker as PM, by a mile).

The Greens and ARD suffered small loses, each losing one seat. I’m not quite sure why the Greens saw their support decrease; it may have seen some of its 2009 voters vote for the DP this year. The ARD was destabilized in 2012 by the resignation of two deputies critical of the leader’s hard-right agenda, and later by the resignation of the embattled party president, who was recently revealed to have been a double agent during the Cold War. The ADR’s vice president was investigated in relation to the fraudulent sale of Hooters’ franchises in Germany.

Smaller parties, however, made gains. The Left was able to win a second seat, although this falls short of its hopes to win between 3 and 5 seats. The KPL also made some very minor gains.

The Pirate Party had a fairly strong showing for its first electoral participation. They might have benefited from the SREL scandal and growing disillusion/dissatisfaction with the political leadership.

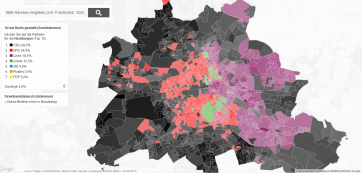

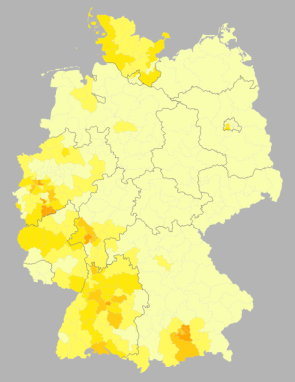

Results of the legislative elections in Luxembourg by commune (source: uselectionatlas.org)

The CSV won 109 of the Grand Duchy’s 116 communes, three fewer than in 2009. Unlike in 2009, the DP won communes – four in total.

The CSV, as your typical Benelux Catholic party, performs best in small, rural municipalities – notably in eastern and parts of northern Luxembourg. The party is weaker in larger urban centres, often polling below its national average, although one of the CSV’s main advantages in electoral terms is the relative homogeneity of its vote share across Luxembourg. The party’s weakest result seems to have been about 26% of the vote, in the industrial southern town of Dudelange.

On the other hand, the LSAP’s weakness is that its support tends to be more regionally concentrated than the CSV but also the other parties (DP, Greens). It draws a disproportionate amount of its vote from the Sud constituency, where it won – by far – its best result with 28.2%, not far behind the CSV. The Sud constituency is the most populous constituency in the country, so we should expect it to contribute a large share of each party’s vote; but in the LSAP’s case, no less than 63% of its votes came from that one single constituency – for comparison, about 51% of all votes cast in the country were cast in the south.

Southern Luxembourg is the most heavily industrialized region of the country, covering the iron-rich Red Lands, and was at the heart of the Grand Duchy’s economy until the 1970s. The region’s economy was driven by iron ore mining, metallurgy and iron working. Hit hard by the steel crisis in the 1970s, industry has markedly declined and most mines or steel mills have shut down, although ArcelorMittal still operates factories in Differdange, Rodange and Schifflange. The south is now poorer, less educated and more blue-collar than the rest of the country, but deindustrialization has seemingly been less traumatic than in neighboring France.

The LSAP topped the polls in two towns in the Red Lands, on the French border: Dudelange (36%) and Rumelange (36%). The party did not top the poll in Kayl, as it had done in 2009, but won a strong 29.6%. In Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg’s second largest city and a former steel town, the LSAP won 25.5%, about 5% behind the CSV. The LSAP performed relatively well in other major industrial towns in the Red Lands including Differdange (21.6%), Pétange/Rodange (22%), Käerjeng (25%), Schifflange (27.8%) and Sanem (26%). Outside the Red Lands, the LSAP did well in middle-sized towns, likely with some sort of industry. In the north, the LSAP topped the poll in Wiltz (36%), a fairly large industrial town (floorcovering, copper, tanneries until the 1960) and a centre of anti-Nazi resistance in 1942. On the other hand, the LSAP performed poorly in white-collar urban centres such as Luxembourg City (14%) and many rural areas. It won less than 15% of the vote in the Centre and Est constituencies and a bit over 17% in the Nord.

The DP’s support is slightly more balanced than the LSAP’s very southern support, although it still has distinctive weak spots and strongholds. The DP polled best, with 25% in the Centre constituency, the country’s most educated and white-collar constituency (it includes Luxembourg City). It also did well, however, in the Nord with 23.7%. It did very poorly, however, in the Red Lands, with only 12.7% in the Sud. Luxembourg City is one of the DP’s traditional strongholds, it won 27% of the vote this year in the capital (34% for the CSV), and it also polls strongly in some adjacent suburbs – Bertrange (28.7%) and Strassen (29.5%). The largest city with a strong DP vote was the affluent spa town of Mondorf-les-Bains, where it placed first with 33% of the vote (a 2-point lead on the CSV).

Surprisingly, the Greens’ vote is not distinctively urban. In fact, it polls best in smaller towns, not far from major urban cores (Luxembourg City) but who have a fairly small population. The Greens won 10.1% in Luxembourg City, a lower result than one might expect from a green party in an educated and white-collar capital city. It did best in towns not too distant from there – its best result was 24% in Beckerich, a town which apparently produces most of its energy needs from alternative sources. The Pirates’ map was also fairly balanced, not doing distinctively better in urban areas – and unlike the Greens, they also did well in more remote northern areas.

The ADR did best in rural areas isolated from major urban areas (although it did well in the post-industrial towns in the south), polling poorly in Luxembourg City (4.4%) and its periphery, but quite strongly (8-10%) in rural towns in the Est constituency.

The Left and the KPL found most of their support in the south. The Left won 5.7% in the Sud constituency, the KPL won 2.8% in the Sud constituency and polled crumbs elsewhere. The Left and the KPL both attracted discontent LSAP voters in the LSAP’s southern strongholds; The Left won 9.7% in Esch-sur-Alzette and did well (5-6%) in Dudelange, Rumelange, Sanem and Differdange. The KPL won over 4% of the vote in Esch-sur-Alzette, Differdange and Rumelange. The Left did, however, do well in the Centre as well (4.8%) and won 5.9% in Luxembourg City.

Jean Colombera’s PID did best, by far, in Colombera’s Nord constituency (3.3%). The Nord cast only 9.7% of the overall votes, but no less than 21% of the PID’s vote came from there. It did best, with 11.2%, in Vichten, Colombera’s hometown.

The statistics on the number of list vs. personal votes is quite instructive. Overall, 60% of voters cast a list vote. List voting was far more common for the smaller parties, whose leaders are less prominent or well-known. Most votes cast for The Left (69.9%), the ADR (72.6%), the KPL (66.4%), the Pirates (72.3%) and the PID (66.7%) were list votes; in contrast, 54.3% of the LSAP’s votes were list votes, as were 58.9% of CSV votes, 59% of DP votes and 57% of Green votes. Personal voting seems more common in the Nord, a majority of DP, Green, LSAP and PID votes in that constituency were personal votes, and a smaller percentage of The Left, the CSV and the ADR’s votes were list votes.

DP leader Xavier Bettel won 32,064 personal votes in the Centre constituency, considerably more than he had won in 2009 (around 19.7k) and more than what LSAP leader Étienne Schneider won in the same constituency (19,682; the LSAP’s 2009 top candidate in the constituency won 25.6k). Bettel also won more personal votes than Luc Frieden, the CSV minister of finance and Juncker’s potential successor.

Juncker, running in the Sud, won 55,968 personal votes (67.1k in 2009). LSAP Deputy Prime Minister Jean Asselborn won 38,257 personal votes in the same constituency. In the Nord, DP lead candidate Charles Goerens, a former cabinet minister and incumbent MEP won 17,523 votes on his name, more than the CSV and LSAP local top candidates.

Conclusion

This election seems likely to usher in dramatic change to Luxembourgian politics – although it doesn’t seem like that from the result. While a CSV-LSAP or CSV-DP coalition, both of which have governed Luxembourg in the last 10 years, would both hold 36 seats. However, during the campaign, the leaders of the LSAP, DP and Greens announced numerous times their desire to oust Juncker from office and did not rule out a three-party anti-CSV coalition, known as a ‘Gambia coalition’ because the three parties’ colours (red, blue, green) are the colours of the Gambian flag.

The leaders of three parties met last weeks and quickly agreed to form a Gambian coalition, led by DP leader Xavier Bettel. Although the DP won less votes than the LSAP, it was the only one of the three parties which gained votes and seats in the election and Bettel was clearly preferred by Luxembourgian voters to his LSAP counterpart, Étienne Schneider. It is a major blow for Étienne Schneider, who had repeatedly said during his campaign that he would be Prime Minister. Now, he will give that job to Bettel, who for his part had downplayed talk of him becoming Prime Minister and only a few months ago stated that he preferred staying on as mayor.

Grand Duke Henri named an informateur on October 23, a non-political person in charge of consulting parties to identify the contending forces and potential governing parties. On October 25, the Grand Duke named Xavier Bettel as formateur, in charge of negotiating a coalition agreement and forming a government. Juncker was not called upon to form a government and the CSV seems resigned to its fate, becoming an opposition party for the first time in decades (the last non-CSV government was 1974-1979). The CSV, however, has decried the Gambian coalition – they feel that as the largest party (by a mile) they should have gotten first dibs at coalition-making and CSV leaders have almost all stated that the Gambian coalition is betrayal of voters’ verdict and trust (voters did not know what they were getting into, the CSV says).

The DP, LSAP and Greens agree on several issues (to be fair, there are no huge ideological gaps between the main parties in Luxembourg on major issues) but also disagree on other fairly important issue. The DP supports liberal economic and fiscal policies, reducing government spending and opposing tax hikes, while the LSAP supports tax increases for the wealthiest and disagrees with the DP when it comes to indexation (as do the Greens, who, however, also oppose tax hikes on the wealthiest). In a way, I figure the Gambian coalition might have something in common with Fine Gael-Labour coalitions in Ireland – not seeing eye to eye on every issue, but sharing a common opposition and distaste for the natural governing party (FF in Ireland, CSV in Luxembourg).

It remains to be seen how stable this arrangement will be, given that it seems to be motivated more by shared opposition to PM-for-life Juncker/the CSV than close ideological affinities. Charles Goerens, the DP MEP elected in the Nord, has already resigned his parliamentary seat, disagreeing with the way talks were conducted (he felt the DP should have talked to the CSV). The coalition might also reflect poorly on LSAP leader Étienne Schneider, who will be neither PM nor Deputy PM after all. Furthermore, it remains to be seen how voters will react to such a coalition.

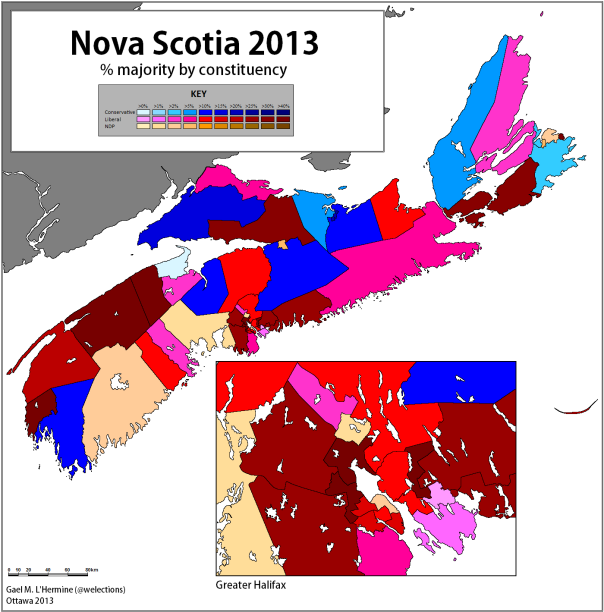

Nova Scotia (Canada) 2013

Provincial elections were held in Nova Scotia (Canada) on October 7, 2013. All 51 members of the unicameral provincial legislature, the Nova Scotia House of Assembly, elected by FPTP in single-member districts, were up for reelection.

The electoral map was significantly redistributed last year, resulting in the net loss of one district: rural Nova Scotia lost three seats, while the Halifax Metro gained two seats. The abolition of four specially designated ‘minority’ ridings – three Acadian seats and one black seat (all of which had smaller populations than the provincial average) – caused a small uproar. The net political effect of the new map favoured the governing New Democrats (NDP), who would have won won two more seats than they actually did in the last election, while the Liberals would have won two fewer seats and the Progressive Conservative (PCs) would have won one seat fewer.

Presentation

Nova Scotia is Canada’s seventh most populous province, with a population just under one million (921,727) in 2011, and is the most populous province out of the four Atlantic provinces. In economic terms, Nova Scotia has the highest GDP of all four Atlantic provinces, although it only accounts for 2.1% of the country’s GDP.

Canada’s Atlantic provinces have tended to be significantly poorer and more economically depressed than the rest of Canada, and all of them were known as ‘have-not’ provinces until recently. Although Nova Scotia is by no means wealthy compared to the rest of Canada, it has historically been better off than other Atlantic provinces, although recent oil-fueled prosperity and growth in Newfoundland has very much altered that. For example, Nova Scotia’s unemployment rate (8.6%) is high compared to the rest of Canada, but it is still the lowest of the four Atlantic provinces. However, Nova Scotia’s GDP per capita is the second lowest of all provinces, and 17.4% of the population were low income after-tax (compared to 14.9% across Canada).

Nova Scotia’s economy is in good part reliant on federal equalization payments, to the amount of $1.458 billion in 2013-14.

The province’s contemporary economy is largely driven by the tertiary sector. The largest industries (NAICS classifications) in 2011 were retail trade (12.6% of the labour force), health care and social assistance (12.3%), public administration (9.7%), education (8%), manufacturing (7%) and construction (6.7%). Traditional industries such as agriculture, fishing and forestry employed only 3.8% of the labour force and mining an infinitely small share (0.8%).

Nova Scotia’s traditional primary and secondary sectors have declined in the last decades. Fisheries once formed an integral part of the provincial economy, due to the proximity of rich offshore (and inshore) stocks, but overfishing in the late 20th century led to the collapse of cod stocks and resulted in major jobs loses and drastic federal quotas on catches. Mining (largely coal) also played a considerable role in the province’s economy, especially on Cape Breton Island (Sydney) although there were fields in Pictou and Cumberland counties on the mainland. Mine closures, in addition to the loss of other major industries (a large steel mill in Sydney) have left Cape Breton Island significantly economically deprived.

Manufacturing and other industries include or have included steel (Sydney – closed down, Trenton), pulp and paper (Liverpool/Brooklyn – closed in 2012, Port Hawkesbury etc), frozen food/fish and agricultural processing (Lunenburg, Oxford, Canso), petroleum refining (Dartmouth), Michelin tires (Bridgewater, Granton, Cambridge) and power generation (Dartmouth, Trenton, Industrial Cape Breton). Shipbuilding in towns such as Pictou or Shelburne used to be major industries (the famous Bluenose schooner, which appears on the Canadian dime, was built in Lunenburg in the 1920s, but declined after the advent of steam and steel.

The Halifax metro has performed better than the rest of the province, benefiting from the concentration of more stable employment in the public sector (including defence – Halifax is home to the large HQs of the CF’s Maritime Command), finance, services, healthcare and education. Halifax’s unemployment rate in September 2013 was 6%, significantly below the provincial but also national average. Halifax is a ‘college town’ home to Dalhousie University, St. Mary’s and the University of King’s College. Antigonish (St. FX) and Wolfville (Acadia) are also major college towns.

Halifax saw the highest population growth between 2006 and 2011 (+4.7%), most other counties lost population. Cape Breton Island has been particularly afflicted by depopulation, having regularly lost population in almost all recent censuses.

Nova Scotia is more ethnically diverse than other Atlantic provinces, although by national standards it is heavily white and native-born. 95% of the population is white, three-quarters of the population was born in the province and 91.8% have English as their mother tongue (French: 3.4%). These statistics hide some interesting tidbits and greater ethnic diversity within the ‘white Anglo’ population.

Blacks constitute 2.3% (about 20,000 people) of the provincial population and form, by far, the largest visible minority in the province. While most black Canadians immigrated to Canada in the more recent past, Nova Scotia’s substantial black population has far deeper roots. Most came as free ‘black Loyalists’ after the American Revolution or as ‘black refugees’ during the War of 1812, and settled in the Halifax area. Many black Nova Scotians faced racism and discrimination, and lived in deplorable conditions. The town of Preston, outside Dartmouth, has a large black majority (69%).

39% of the population reported their ancestry (multiple response) as ‘Canadian’, a term which seems to indicate a long-time, settled Anglo-Protestant population which has lived in Canada for hundreds of years. Some 73% reported European ancestries, the largest being Scottish (31.2%), English (30.8%), Irish (22.3%), French (17%) and German (10.8%). This gives Nova Scotia the second highest proportion of persons claiming Scottish and Irish ancestries and the third highest proportion claiming English ancestry of all provinces or territories.

Like in New Brunswick, many English Nova Scotians are of United Empire Loyalist descent and settled in the province following the American Revolution. Cumberland County, Shelburne County and the Annapolis Valley have the largest English populations. Most Scots settled on Cape Breton Island or Pictou County; over 50% of the population in Pictou, Inverness and Victoria counties (the last two are on Cape Breton) and Gaelic was widely spoken in northern Nova Scotia and parts of PEI until the late 19th century. Most Irish are found in Antigonish County.

Nova Scotia remains a small French/Acadian minority, and an even smaller French-speaking minority. Those claiming French ancestry are concentrated in Yarmouth and Digby counties in southern NS or in Richmond County (Cape Breton Island), with some sizable numbers in Inverness and Antigonish counties. 30.5% of the population of Digby County claim French as their mother tongue, and Francophones constitute about three-fifths of the population in Clare municipal district. There are isolated French-speaking communities in Yarmouth County (20.3%), Richmond County (Isle Madame, 22.8%) and Inverness County (Chéticamp, 13.1%). Acadians in other parts of the province, notably Antigonish or Guysborough County, have been Anglicized.

Nova Scotia has the largest German (and Dutch, 3.6%) population of the Atlantic provinces. A significant German Protestant population settled in Nova Scotia, particularly Lunenburg County, during early British colonial rule – they were brought in as ‘Foreign Protestants’ by the British to counterbalance the Acadian and native (Mi’kmaq) populations after Britain acquired Nova Scotia from the French. Lunenburg County, by far, still has the largest German population in the province; 32.1% claimed German ancestry in 2011.

76% of the Nova Scotian population is Christian and 21.8% have no religious affiliation. In more detailed terms, 33% of the population is Catholic, 12.1% are adherents of the United Church of Canada, 11% are Anglican and 8.9% are Baptist. The relatively large Anglican population and the large Baptist population (second largest, proportionally, after New Brunswick) is a sign of the province’s large stock of descendants of the United Empire Loyalists. Catholics constitute a large majority of the population on Cape Breton Island, with the exception of Victoria County, which saw more English settlement; and also in Antigonish County. Pictou County, Guysborough County, Halifax County and the Acadian counties of Digby and Yarmouth also have sizable Catholic populations; in contrast, the Catholic population in the Anglo/German counties is quite small. The contentious issue of religious schools, which has been a hot topic of religious (and linguistic) strife in Canadian history, was settled prior to Confederation in Nova Scotia (in 1865) with the adoption of non-denominational schools and allowed after-school Catholic religious education in schools.

Political culture

Nova Scotian political culture is both similar to and dissimilar to the general political culture of the Atlantic provinces. As in other provinces, provincial politics have been highly influenced by parochialism, tradition, conservatism, pragmatism and a dose of cynicism and caution. However, unlike in the other provinces, the traditional Liberal/Conservative duopoly in provincial politics has been successfully challenged by the NDP.

Ideology and issues have played a relatively minor role in Nova Scotian politics, historically. Since pre-Confederation days, observers have pointed out that few if any meaningful issues or ideologies divided the Liberals and the Conservatives. Both parties reached their positions more on grounds of political expediency rather than principles; for example, the early Liberals opposed expanding the franchise and fought against abolishing the upper house. To this day, both the Liberal and Conservative (PC) parties are moderate, pragmatic and ideologically similar parties while the incumbent NDP government adapted itself to the terrain and governed in a similarly moderate and fairly non-ideological fashion.

No great ethnic, religious, class or ideological antagonisms have had a strong, lasting influence in Nova Scotian elections. Some ethnic and religious voting patterns have been evident, notably with Acadians in particular and Catholics in general tending to lean towards the Liberals. However, unlike in many other Canadian province, the religious cleavage in vote choice at the provincial level has been far less pronounced. Religion and religious conflict has played a role in Nova Scotian politics, notably in pre-Confederation days or in 1954, but the ‘schools question’ was never a major political issue in the province and both parties effectively catered to both Protestants and Catholics. The provincial Conservatives have been considerably less hostile towards Catholics than their counterparts in other provinces and, as a result, they have at times managed to appeal strongly to Catholic voters.

Class politics and the union movement (with industrial workers in steel mills and coal mines) have been more prominent in Nova Scotia than in the other Atlantic provinces, explaining the strength of the CCF/NDP compared to other Atlantic provinces. Class politics and unionization ran highest on Cape Breton Island, historically more influenced by post-Confederation immigration and the tenets of British trade unionism, and Cape Breton Island is where the labour movement found most of their support. However, with that exception, class consciousness has never been particularly high in the province.

Family ties, traditional loyalty, local caution and conservatism as well as patronage sustained the Liberal/Conservative duopoly for well over a hundred years. Patronage in the public sector subsisted well into the 1950s, and pork-and-barrel ‘highway politics’ or the granting of government contracts to party friends continued to be the rule well beyond that. Today, while partisan loyalties are much less solidly entrenched, personality and local party organization plays a large role.

Political history

Nova Scotia had a long and rich political history prior to it joining Canadian Confederation in 1848. The House of Assembly was the first legislature in Canada, created in 1758, and Nova Scotia was the first British colony to gain ‘responsible government’ (government responsible to the elected legislature) in 1848, under the leadership of Joseph Howe – who had already led to the creation of the Liberal/Conservative party system in 1836. When Nova Scotia joined Confederation, it did so under the leadership of the pro-Confederation Conservative Premier Charles Tupper (1864-1867).

However, the majority of Charles Tupper’s constituent did not follow him into embracing Confederation with the Canadas in 1867. When Nova Scotia joined Confederation, it was still experiencing a ‘golden age’ because of reciprocity, shipbuilding, lucrative custom duties and international trade; the conservative and cautious people of Nova Scotia, fearing the loss of self-government and the imposition of direct taxation (a major issue in early provincial politics), resisted Confederation.

You think that Quebec was the first Canadian province to elect an outright separatist government in 1976? Think again. Nova Scotia, in 1867, spearheaded by anti-Confederation leader Joseph Howe, elected an overwhelmingly anti-Confederate majority both to the House of Commons in Ottawa (17 of the province’s 18 seats) and to the House of Assembly in Halifax (36 anti-Confederation Liberals against 2 pro-Confederation Conservatives). Joseph Howe immediately went to London to attempt to “repeal” Confederation, but the British refused and Howe quietly accepted the resolution, as did most of his partisans (although the Liberal/anti-Confederation Premier of Nova Scotia, William Annand, proved more radical, but he was a non-entity and was pushed out in 1875). In a sign of the legendary pragmatism of Nova Scotia’s politicians, Howe and most of his followers decided to seek “better terms”for Nova Scotia within Canada – he went as far as joining Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s cabinet as President of the Privy Council (1869-1873) and Secretary of State for the Provinces (1869-1873). Likewise, 10 Anti-Confederation MPs in Ottawa joined Macdonald’s very pro-Confederation Conservatives. However, the anti-Confederation party in provincial politics evolved to become the provincial Liberal Party.

Between 1867 and 1956, Nova Scotia had a one-party (Liberal) dominant system – the NS Liberals governed between 1867 and 1878, between 1882 and 1925 and again between 1933 and 1956. The Liberals’ 43-year old on power between 1882 and 1925 remains, to date, the longest unbroken one-party hold on power in Canada, although the Alberta PCs will break that record in September 2014. The Conservatives won the 1878 election because of a recession, but the Liberals regained power in 1882 and entrenched themselves.

The long era of provincial Liberal dominance, not replicated in federal elections, owed a lot to strong organization (the Liberals built a strong, cohesive province-wide organization, while the Conservatives did not organize province-wide until 1896 and had weak local branches until the 1950s) and able leadership. Indeed, the provincial Conservatives lacked strong leaders: able Tory leaders made their mark in federal, not provincial, politics until the 1960s: Nova Scotians John Thompson, Charles Tupper and Robert Borden all served as federal Tory leaders and Prime Minister of Canada, years later Robert Stanfield took the leadership of the federal PCs during the Trudeau era. In contrast, provincial Tory leaders usually served short periods of times, many failed to win their seats and none of them left a mark on provincial politics unlike the succession of long-serving Liberal Premiers until 1954.

FPTP magnified and exaggerated the winning party’s majority in the legislature, but the popular vote was often far tighter than the seat count. Between 1871 and 1945, the Conservatives dropped below 40% of the vote only once (1920); the Liberals’ best PV result was 56.7% and dropped below 40% only once between 1867 and 1963.

William Stevens Fielding, the Liberal Premier between 1884 and 1896, was the province’s first major Premier. In the 1886 election, angered by Macdonald’s treatment of NS and opposing the Conservatives’ fiscal and tariff policies, Fielding ran on a separatist platform calling for repeal of Confederation. He handily won that election, but he was unable to do that and he quickly became a pragmatist in the line of Joseph Howe. Fielding was the first Premier who took a more active interest in the workings of government, with projects such as building roads and inducing outside interest in developing the province’s coal reserves. Along with Ontario Liberal Premier Oliver Mowat, he became a powerful advocate for provincial rights and in 1896, after helping Wilfrid Laurier’s federal Liberal electoral campaign in NS, resigned to join the federal cabinet where he had a long and illustrious career as Minister of Finance between 1896 and 1911 and again between 1921 and 1925.

His successor as Premier, George Murray, ruled the province for 27 years between 1896 and 1923. This is the longest unbroken tenure for a Canadian head of government, but Murray made no mark on Canadian history and is not as prominent in provincial history as his predecessor and some of his successor. Murray was an affable, moderate and pragmatic leader who was a master of patronage and brokerage politics, carefully balancing labour and capital interests. He was, however, not an innovator – he admitted as much himself, saying he did not want to be a vanguard of public opinion. He refused any initiative which had not proven successful in Ontario.

The 1920 election represented a short-lived deviation from the established political order. United Farmers and Labour candidates won 30.9% of the vote against 24.7% for the Conservatives, forming the Official Opposition with 11 members to the Tories’ 3. The industrial working-class had been hit by the post-war slump, increased freight rates, lower demand for steel, the steep rise in the cost of mining coal and the long, expensive haul to central and western Canadian markets. The Independent Labour Party was formed on Cape Breton in 1917 and on the mainland in 1917. Farmers had widely divergent interests but the economic difficulties, dissatisfaction with the political order and a wage-price squeeze briefly allowed them to federate as their brethren did, with even more success, in Ontario and the Prairies. The United Farmers of Nova Scotia were born in 1919. Murray aptly called an election before either new group could get organized and the press widely denounced them as socialists and Bolsheviks. Once elected, the Farmer-Labour group made a poor impression and the Conservatives quickly recovered.

Indeed, the Conservatives won the 1925 and 1928 elections by attaching themselves to the Maritime Rights movement, active in the 1920s, and effectively serving as the spokesman for discontented Nova Scotians prior to the Great Depression. The Conservatives won 40 out of 43 seats in 1925, and the new Premier, Edgar N. Rhodes, demanded genuine financial concessions from Ottawa in terms of trade, taxation, fisheries and freight rates. Other achievements included abolishing the upper house, administrative reform, teachers’ pensions and allowances for widowed mothers. However, having been reelected by a tight margin in 1928, the Conservatives were in office when the Great Depression struck and where thrown back out of office by the Liberals in 1933.

Angus L. Macdonald, the Liberal Premier between 1933 and 1940 and again between 1945 and 1954, became one of Nova Scotia’s most famous Premier. Macdonald was an impressive orator, a master of new means of communication, had an engaging personality and an attractive biography – a man who rose from humble Catholic Gaelic origins on Cape Breton Island to become a leading law professor. Macdonald perpetuated old Nova Scotian political traditions of patronage, pork-and-barrel road construction (highway politics) and rewarding party friends with jobs and contracts; but Macdonald favoured a more interventionist and activist government, both provincially and federally, than Murray had. His government introduced old age pensions, passed modern labour/union legislation, paved roads and promoted rural electrification. Macdonald, like many of his predecessors, was a vocal advocate of the province’s interests in federal-provincial relations. He argued in favour of federal aid to provinces based on province’s needs, and that Ottawa should assume full responsibility and exclusive jurisdiction over unemployment insurance, old-age pensions and mothers’ allowances.

With the outbreak of war and the 1940 federal election, Macdonald became Minister of Defence in Mackenzie King’s federal Liberal wartime government in Ottawa between 1940 and 1945. He was replaced as Premier by his Highway Minister, A.S. MacMillan, whose five-year tenure was relatively unremarkable but gave the Liberals a third term in office in the 1941 election, which was the first election in which the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), today’s NDP, won seats (it had won its first seat in a 1939 by-election), taking three seats – all from Cape Breton, where the CCF had been endorsed by District 26 of the UMW.

Macdonald returned home in 1945 and took his old job back. Less than two months later, he led the Liberals to a landslide victory in which the Conservative vote fell by 13% to 33.5% and were completely shut out of the legislature, leaving the CCF’s caucus of two (both from Cape Breton) to assume the role of Official Opposition. However, as in 1920, the Conservatives had a phoenix-like rising from the ashes, under a young Robert Stanfield, who became the PC leader in 1948.

Macdonald continued his advocacy for provincial rights in his second term and invested heavily in education, although his second term – from 1945 to his death in 1954 – was not as successful as his first term. The Liberals won reduced, albeit comfortable, majorities in 1949 and 1953. The PCs were reborn, while the CCF maintained a small and very regionalized (Cape Breton) presence in the legislature until they lost their last Cape Breton seat in 1963.

When Macdonald died in 1954, the Liberal Party split along confessional lines, with the Liberals ousting Macdonald’s successor as (interim) Premier, the Catholic Harold Connolly, in favour of the Protestant Henry Hicks. Hicks took the ill-advised decision of raising taxes to finance the provincial education system. This, combined with the loss of Catholic support due to the 1954 confessional split, led to the Liberals’ defeat against Stanfield’s PCs in the 1956 election. It was very close contest, one of the few which didn’t result in an awfully disproportional seat count, but 1956 – or perhaps Stanfield’s landslide third term reelection in 1963 (56% and 39/43 seats) – marked the definitive end of Nova Scotia’s one-party dominant era and the long period of Liberal rule broken by short-lived and forgettable Tory administrations.

Stanfield came from a rather different social milieu than Macdonald – part of a wealthy Truro WASP textile family, but he was a hard-working, honest, and humble man and gained the same slightly paternalistic, elitist ‘father figure’ image that Macdonald had. Stanfield, who was Premier of Nova Scotia until he won the federal PC leadership in 1967, was the quintessential Red Tory – centrist, pragmatic, supportive of government intervention, moderate if not progressive. Under his premiership, the provincial government played an active role in the province’s economic development. Some of his government’s policies included increased funding for education, comprehensive secondary schools, removing the worst aspects of party patronage (creating a professional bureaucracy and respecting the Civil Service Commission, set up in 1935 but used by the Liberals as a shield for their patronage) and setting up a hospital insurance scheme. More famously, he created a Crown corporation to attract private investment to the province – including a heavy water factory, a colour TV factory and auto assembly plants.

Stanfield was replaced by G.I. “Ike” Smith, whose term was plagued by economic problems. The owner of the Cape Breton coal mines and steel mills had announced in 1965 its intention to close its mines on the island within 15 years, which led the federal Liberal government, in 1967, to nationalize the mines in a new Crown corporation which would focus on operating and phasing out the mines and developing new economic opportunities. In 1967, that same company announced the closure of its Sydney steel plant, leading Smith’s government to nationalize Sydney Steel. The province was also forced to take ownership of the colour TV factory and a heavy water plant. Smith’s tenure was not without its achievements, but the PCs narrowly lost the 1970 election to Gerald Regan’s Liberals, with a minority government. The NDP won two seats, again on Cape Breton, the first seats in seven years.

During the campaign, Regan had said that he found Smith too socialistic, but that didn’t keep the Liberals from favouring government intervention just as much. To be sure, Regan’s election ushered in a more businesslike and technocratic style, but the government played a large role in promoting offshore oil and gas exploration on Sable Island and created a new publicly-owned power system (Nova Scotia Power) by taking over a privately-owned company. The Liberal government provided free drugs for pensioners, free dental care for schoolchildren, formulated Canada’s first freedom of information act and introduced collective bargaining for fishermen and public servants. Regan’s Liberals were reelected in 1974, defeating the PCs, led by the more populistic John Buchanan since 1971.

However, voters punished the Liberals for high utility prices, a poor economy and unfulfilled promises in the 1978 election, in which the PCs won 31 seats to the Grits’ 17 and a record 4 seats for the NDP (again, all from Cape Breton). The NDP’s difficulty to win seats on the mainland upset the party’s Haligonian party establishment and led to internal battles. The middle-class and ‘urban progressive’ Haligonian win won out, with Alexa McDonough, but a rogue Cape Breton MLA, Paul MacEwan, was expelled from the NDP in 1980 and founded the Cape Breton Labour Party in 1982, which emphasized working-class issues more than the new Haligonian NDP leadership.

Premier John Buchanan’s PCs were reelected in 1981, in which the Liberals won only 33% of vote and in which the NDP won its first seat on the mainland (MacEwan was reelected on Cape Breton). Buchanan’s government negotiated an offshore development agreement with Ottawa and reorganized the fisheries sector; on the other hand, he faced a number of economic and political problems. The man who would later become known as ‘Teflon John’, however, remained very popular with voters, who liked his ‘down-to-earth’ populist style. He was reelected with an increased majority in 1984, while the Liberals won only 31% and 6 seats – their leader not among them. The NDP, criticizing the government’s cuts in social services, won three seats – all on the mainland this time.

Buchanan’s third term proved difficult. Oil and gas exploration gradually stopped after an underwater gas well exploded and federal oil grants were phased out. The industrial town of Glace Bay (Cape Breton) was hit hard by a mine fire, a fisheries plant burning down and the closure of the two heavy water plants by Ottawa – while Sydney Steel continued to face a host of problems. Other parts of the province, however, saw greater economic success.

The PCs were plagued by a variety of scandals involving many cabinet ministers and PC MLAs. For example, the Deputy Premier was forced to resign after revelations that he had pressured banks to write off some $140,000 in personal loans in 1980 and the attorney general’s office had later interefered with an RCMP criminal investigation into the matter. The government was also hurt by a judicial inquiry into the case of a Mi’kmaq man convicted to 11 years in jail for a murder he did not commit; the investigation revealed incompetence, racism and coverups from police, the judicial system and attorney generals since 1970.

Despite these scandals, “Teflon John” managed to win a fourth term in office in 1988, although with a significantly reduced majority: the PCs won 28 seats to the Liberals’ 21 and the NDP’s 2 seats. The fourth term is a classic example of “one term too much” – it was a real trainwreck for the PCs, and led to a Liberal landslide in the 1993 election. Nova Scotia and most of Atlantic Canada’s economies suffered in the 1990s, and NS was badly hit by the fisheries crisis which meant a major decline in the fishing industry and job loses in the fish processing industries. If that was not bad enough, the wave of scandals which had begun hitting the PCs before 1988 became a tsunami which went up to the Premier himself. A former cabinet minister implicated Buchanan in cases of corruption and nepotism; it came out after he resigned from office that Buchanan had received about $1 million in PC party funds while he was Premier, including $40,000 annually to supplement his salary.

Buchanan resigned in September 1990 and was named to the Senate by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. His successor, after a PC convention, was Donald Cameron, who was left with the unenviable job of picking up the pieces. Cameron tried to clean up government and passed landmark conflict of interest, party financing and human rights legislation. The 1991 budget froze public sector wages and cut 300 jobs in the governments, and in 1992 he privatized Nova Scotia Power. His efforts to rebuild were hurt by the revelations of Buchanan’s finances, and by a 1992 mine disaster which killed 26.

John Savage’s Liberals won a landslide in the 1993 elections, taking 40 seats out of 52 and reducing the PCs to only 9 MLAs. Savage was confronted with a terrible economic situation, which forced the Liberals to introduce a string of unpopular austerity budgets. Savage raised the sales tax, imposed a surtax on high incomes, curbed public sector wages, cuts jobs in the public sector and made major spending cuts in education and healthcare. Influenced by New Public Management tenets including ‘efficiency’, ‘privatization’ and ‘downsizing’, Savage at first cut back on patronage appointments and reformed the public sector, but Liberal pressure forced him to loosen his stance on patronage appointments. Savage was compelled to resign in 1997, and was replaced by Russell MacLellan.

The 1998 election was a turning point in NS history. Although the Liberals won the most votes and 19 seats, the NDP made major gains and formed the Official Opposition, with 19 seats (up from 3), leaving the PCs with 14 seats. A year earlier, in the federal election, the NDP had won 6 seats in the province while the federal Liberals were shut out entirely due to Prime Minister Chrétien’s unpopular cuts to unemployment insurance and other programs. MacLellan remained in office for a bit over a year, forming a minority government with PC support. In July 1999, John Hamm’s PCs won a majority government with 30 seats against 11 apiece for the NDP and Liberals.

Under Hamm’s first term, Cape Breton Island’s remaining steel mills and coal mines shut down entirely (in 2001). The PC government sold off Sydney Still Corporation, the provincially-owned operator of the Sydney steel mill. The federal Crown corporation in charge of the coal mines, DEVCO, sold all surface assets in December 2001. Otherwise, the PC government balanced public finances and cut taxes. Hamm’s PC government was reduced to a minority in the 2003 election, winning 25 seats to the NDP’s 15 and the Liberals’ 12.

Hamm stepped down in late 2005 and was replaced by Rodney MacDonald, who sought a mandate of his own in June 2006. The PCs gained 3% in the popular vote, but suffered a net loss of 2 seats, being reduced to 23 seats against 20 for the NDP and a pitiful 9 for the Liberals, who, with only 23% of the vote, won their worst result ever.

MacDonald’s government, worn down by some scandals, lost a confidence vote and was defeated by Darrell Dexter’s NDP in the June 2009 election. The NDP made major gains in both the popular vote and seat count, winning 45% of the vote and a majority government with 31 seats. The Liberals made smaller gains, winning 27% of the vote and 11 seats, but this was enough to place them in second. The governing PCs fell to third place with only 24.5% of the vote and 10 seats.

Campaign and issues

Dexter, forming the first NDP government anywhere in the Atlantic provinces, governed in a very moderate fashion, going out of his way to appear as a centrist and ‘reasonable’ leader; something which has worked well for the NDP in Manitoba or Saskatchewan but didn’t prove successful for Dexter in NS. His government’s record was mixed, hardly a disaster but failing to live up to the high expectations voters had set in the NDP in 2009.

Dexter’s backers point to his government’s fairly solid economic record. The province is projected to post a $18.3 million surplus (0.04% of GDP) in FY 2013-14 – one of only four provinces to do (BC, SK, QC, NS) and real GDP growth for 2013 is expected to be 1.7%. It had balanced the budget in 2010-11 but posted a small deficit since then. Credit rating agencies gave the province high ratings.

His critics on the left, however, accuse him of doing so by embracing austerity (while the right criticized him for raising taxes). Dexter’s government made substantial funding cuts to education, health care and post-secondary education over a four-year period estimated at $772 million. It lifted the freeze on tuition fee increases, and undergrad tuition fees in the province have increased to an average of $5,934/student in 2012-13, one of the highest in the country. With unions, Dexter’s government proved only marginally more friendly than his predecessors’ governments, making some fairly limited changes to trade union legislation, although critics claimed that his changes were still too friendly to unions. The NDP was called out by left-leaning think-tanks such as the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) for doing little to improve labour standards. The left also criticized Dexter for abandoning rent control, a measure which was welcomed by landlords and business.

Above all, perhaps, Dexter got lots of flack from the left for ‘corporate welfare’, ostensibly to create jobs. The government gave millions of dollars in loans or tax breaks to business including shipyards, an aquaculture firm and Imperial Oil. Were these wise investments which will create jobs in the long-term? Time will tell, but the NDP’s left-wing base didn’t like the optics of it much.

By his first year in office, Dexter was hit by the MLAs expenses scandal, in which the Auditor General reported that many MLAs – from all parties, and incidents predating the 2009 election – had filled excessive or inappropriate expense claims. The scandal, again, hit all three parties – two Liberal, one PC and one ex-NDP MLAs were all forced to resign – and Dexter himself had questionable expense claims of his own. Dexter’s government did a poor job of handling the scandal, in the process voters – who a few months earlier had seen the NDP as something new and a breath of fresh air – got angry at the government and disillusion set in.

A major factor which has been cited to explain the NDP government’s unpopularity was that the party quickly lost touch with rural Nova Scotia, where the NDP had done tremendously well in 2009. The province’s economy has not been too shabby, but Halifax is one of the few regions which has actually prospered since the NDP came to power, while rural NS declined. To add to this perception of rural/urban disparities in growth, the NDP fumbled a number of rural issues, the most noteworthy of which was the December 2009 cancellation of the Yarmouth Ferry, which connected the southern municipality of Yarmouth with Maine; to make matters worse, the government announced and handled this decision in a aloof, disconnected manner which gave a strong impression that the NDP just “didn’t get” rural NS.

The government, as aforementioned, was far from being a total disaster. On healthcare, the NDP was able to find a strong middle ground between closing rural ERs and keeping them open, in the form of Collaborative Emergency Care Centres (miniature ERs in small communities with paramedics and nurses). Although the cuts to education were criticized by some, others welcomed Dexter’s trimming of the education budget, arguing that the government was challenging school boards to identify savings and tackle the decline in elementary and secondary school enrollment. On environmental issues, the NDP government took a fairly strong stance on climate change and especially wilderness protection. The government’s energy policy hasn’t been well received by voters (disliking an increase in power rates), the opposition) and some industries (natural gas and wind power), but Dexter’s ‘Maritime Link’ scheme to to receive electricity from Muskrat Falls in Labrador has generated some positive responses. The project would diversify NS’s energy sources and reduce its historical dependence on fossil fuels.

The NDP platform’s main planks included continuing to deliver balanced budgets (and decrying the ‘financial recklessness’ of the Liberals and PCs), reducing the harmonized sales tax (HST) by 1% a year in 2014 and 2015 to reduce it to 13%, taking the HST off ‘family essentials’ (strollers, children’s car seats) and keeping it off home energy, capping elementary school class sizes at 25 students, defending the Maritime Link project, adding five new Collaborative Emergency Centres and open clinics staffed by nurse practitioners.

The Liberal platform did not delve deep into specifics and was filled with flowery language and pablum. The main planks emphasized by the Liberals included “standing up to Nova Scotia Power” by breaking Nova Scotia Power’s private monopoly and creating a regulated, competitive energy market; job creation (focusing on small businesses); balanced budgets (and criticism of the NDP’s corporate ‘handouts’); reinvesting in education after NDP cuts; healthcare and seniors. Deregulation of the energy market is a fairly right-wing plank, and the Liberal platform used populist rhetoric on the matter (‘enough is enough’, ‘standing up to Nova Scotia Power’ etc). The Liberals pledged to reduce the HST, but only when the province reaches a sufficient budget surplus. On healthcare, the Liberals proposed to cut provincial health boards from 10 to 2 and use savings to pay for more family doctors and reduce hip/knee replacement time. On education, the Liberals platform called for capping KG-Grade 2 classes to 20 students and Grades 3-6 classes to 25 students. On issues such as education, the Yarmouth Ferry or community services it does seem like the Liberals took populistic stances challenging the NDP on issues where its performance was criticized.

In one of the ironies of Atlantic Canadian politics, the PCs might have been to the left of the Liberals in this campaign (although it’s a rather pointless point to argue), especially as the Liberals came to be defined with their ‘standing up to Nova Scotia Power’ stuff. On the issue of energy, for example, the PCs proposed to freeze electricity rates for five years (magically?) and lower renewable energy targets. Other PC platform planks included cutting the HST to 13%, creating 20k jobs (again critical of the NDP’s corporate welfare), reducing school boards from 10 to 4, cutting the number of district health authorities from 10 to 3 and a derided goal to increase the provincial population to 1 million by 2025.

The Greens, who ran a full slate in 2009, only nominated 16 (/51) candidates this year. Their platform, for what it’s worth, included funding public rail transit across the province, mandating Nova Scotia Power to use 100% renewable energy by 2020, introduce a guaranteed annual income and removing parental income as a factor in student loan system.

Results

Turnout was 59.08%, virtually unchanged from last time (58%). This is, by recent historical standards, very low. Changes compared to the 2009 election.

Liberal 45.71% (+18.51%) winning 33 seats (+22)

PC 26.31% (+1.77%) winning 10 seats (+1)

NDP 26.84% (-18.4%) winning 7 seats (-24)

Greens 0.85% (-1.49%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Independents 0.3% (-0.38%) winning 0 seats (nc)

For once, the pollsters were right. Canadian pollsters have had a tough time, for some reason, calling provincial elections; the most recent and memorable case being that of the BC provincial election in May; the BC NDP was widely expected to defeat the incumbent BC Liberal government, but the Liberals were reelected with a substantial margin of victory over the NDP. Some believed that the same thing could happen in Nova Scotia, although the NS Liberals’ lead in polls in the final stretch was far larger than any lead the BC NDP (or Alberta Wildrose in 2012) held in the final stretch; the NS Liberals led the NDP by about 20 points in all the final polls.

The pollsters generally correctly predicted the Liberals and NDP’s share of the vote, perhaps slightly overestimating the Liberals (but by 1-2% at most) and NDP (again by 1-2% at most). In turn, they underestimated the PCs by about 1-3%.

What was most surprising about the results was how poorly the NDP ended up doing: not only did they get trounced for reelection (unsurprisingly) but they placed third in the seat count, meaning that Jamie Baillie’s PCs will form the Official Opposition to the Liberal government; the first time the NDP has failed to place first or second since 1993 (which predates the emergence of the NDP as a potent force in NS politics) and the worst NDP result (in seat and % terms) since that same date. The NDP did place second ahead of the PCs on the popular vote by a few decimal points, but they won 3 seats less than the PCs did; mostly, I think, because the NDP got screwed over in Halifax, which was also rather surprising. Premier Darrell Dexter lost his own seat by 31 votes to the Liberals – one of those surprising Liberal gains in the HRM.

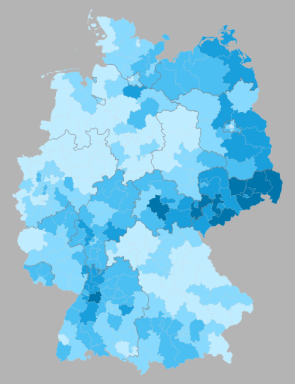

I haven’t analyzed the NDP’s vote distribution at all, but I have a hunch that its vote was more evenly distributed than the PC vote and, hence, ended up losing a number of tight races to the Liberals/PCs. What is also remarkable, by glancing at my map’s shading above, is how tight almost all of the NDP seats ended up being. The NDP did not win any seat with a margin over 10%; in fact their biggest victory was a 5.8% margin in Truro-Bible Hill-Millbrook-Salmon River and a 5.6% margin in Sydney-Whitney Pier (a 573 vote majority). About 2,100 less votes for the NDP would have wiped them out and 2,100 votes extra would allow them to have 15 seats.

In any case, Stephen McNeil’s Liberals won a large majority government, basically as impressive as Dexter’s NDP majority government in 2009. Unlike Dexter, McNeil was not able to thoroughly sweep rural areas – but he won his majority government by nearly sweeping the HRM (Halifax metro) and performing fairly well in rural parts of the province outside the old Grit stronghold in the Annapolis Valley and the Acadian counties.

I explained some of the reasons for the NDP’s unpopularity above. A large part of the explanation can be summarized as being that the NDP failed to live up to the unreasonably high expectations that voters had placed in them in 2009, failed to create the “new politics” which everybody promises but which no politician actually delivers (of course) and forgot about its core electorate in going out of its way to appear as a centrist, fiscally responsible governing party. When you had these explanations to Nova Scotia’s contemporary political culture: low polarization, a very fickle electorate and three parties which run around in a circle ideologically; and the NDP’s defeat makes sense.