The far-right: Le Pen

< previous chapter: Parties, Candidates, Issues and Campaigns – The radical left (FI), J.-L. Mélenchon

The French far-right is one of the strongest – and oldest – in western Europe. The National Front (Front national, FN) has won at least 10% of the vote in nearly every national-level election since the 1984 European elections, the FN’s first electoral breakthrough. Most famously, its candidate qualified for the second round in the 2002 presidential election, with a second place finish in the first round ahead of PS candidate – and incumbent prime minister – Lionel Jospin. The French far-right is also a family enterprise. The party was led between 1972 and 2011 by Jean-Marie Le Pen, who was the FN’s candidate in five presidential elections (1974, 1988-2007); he was succeeded in 2011 by his daughter, Marine Le Pen.

The story of the French far-right and the FN

Nationalist populism has a long history in France, between boulangisme in 1889 or poujadisme in 1956, and the contemporary discourse and ideologies of the far-right are in part inspired by these past movements, particularly poujadisme. Prior to the FN, however, past right-wing populist or nationalist movements had been ephemeral flash in the pans or ‘fevers’, rarely lasting for more than one election and often falling prey to infighting and atomization. Jean-Marie Le Pen, therefore, managed to do something remarkable: seize control of a far-right party, impose himself as its uncontested leader and attract lasting popular support.

The roots and the rise (1970s-1997)

The FN was founded in 1972 as the political front of Ordre nouveau (ON), a neo-fascist and violently anti-communist far-right movement. To present a respectable public face, they invited Jean-Marie Le Pen to be the new party’s president. Le Pen had been a poujadiste and later CNIP deputy (1956-1962), first elected at the age of 27, and was far-right candidate Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour’s campaign manager in the 1965 presidential election. Le Pen, with no strong personal ties to any of the post-war far-right/neo-fascist movements and groups, came from a different ideological tradition: Poujadist, ‘Algérie française‘ , nationalist, reactionary/conservative, staunchly anti-communist and anti-intellectual; closer to Charles Maurras’ Action française (minus the monarchism) than to fascism. Le Pen’s intellectual and ideological references were vaguer, and he had little interest in neo-fascists’ racist/ethnocentric visions of a united white European civilization (even less in the neo-paganism) – although he was later inspired by Third Position or the Nouvelle Droite‘s ethno-differentialism.

ON’s goal in creating the FN was to mimic the successful neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI) – imitated down to the emblematic tricolour flame logo – by integrating both ‘nationalist-revolutionaries‘ (nationalistes-révolutionnaires) and traditional conservatives (‘nationals’ or nationaux) like Le Pen into a single party. Le Pen, however, quickly marginalized the ON ‘nationalist-revolutionary’ elements and imposed himself as the líder máximo. Having lost control of the party, many ex-ON members (Alain Robert, François Brigneau) left the party within a year and eventually created the Parti des forces nouvelles (PFN), the FN’s competitor for control of the far-right until the early 1980s. Nevertheless, some ‘nationalist-revolutionaries’ and assorted neo-fascists remained in the FN – Victor Barthélemy (wartime collaborator and member of Jacques Doriot’s PPF), François Duprat (Holocaust denier, killed in 1978), Pierre Bousquet (Waffen SS Charlemagne division corporal, quit in 1983) and, most importantly, Jean-Pierre Stirbois, leader of the ‘Solidarist’ faction of ‘nationalist-revolutionaries’ and the FN’s ‘number two’ until his death in 1988. Nevertheless, except for Stirbois, most of the old neo-fascists or ‘nationalist-revolutionaries’ lost influence in the FN once it became a major party. Given Le Pen’s political background and his acrimonious relations with the nationalist-revolutionaries, the FN cannot be considered a fascist party – even if the party has included some neo-fascist members and has had troubling ties to neo-fascist groupings.

Hobbled by the PFN’s competition, the FN remained only a minor micro-party until 1983/1984 – in his first presidential candidacy, in 1974, Le Pen won only 0.75%. The FN had limited local successes in 1982 and 1983, most famously in a fall 1983 municipal by-election in Dreux (Eure-et-Loir) in which it won 17% of the vote, but its national electoral breakthrough came in the 1984 EP elections, in which the party – almost out of the blue – won 10.95% and elected 10 MEPs. Between 1984 and 1998, the FN’s electoral growth was gradual but consistent: Le Pen won 14.4% in the 1988 presidential election, then 15% in 1995. The FN’s growth in legislative and local elections, where its local candidates lacked Le Pen’s notoriety or draw, was slower but eventually caught up with the FN’s presidential results – 14.9% in the 1997 legislative elections, qualifying for 124 runoffs (76 three-way triangulaires); 15% in the 1998 regional elections.

Why and how the FN grew

The FN emerged during a period of significant socioeconomic and political change in France. Three decades of rapid economic growth and rising standards of living (the Trente Glorieuses, average annual GDP growth of 5.6% between 1950 and 1974) came to an end with the oil crises of 1973 and 1979, and economic growth since then has been slower and more volatile (annual average of 2.3% between 1975 and 2006). A full employment economy has become an economy with one of the persistently highest unemployment rates in the EU. Public finances have been in the red since the 1970s. Globalization and European integration have deepened socioeconomic inequalities, creating ‘winners’ and ‘losers’, with the ‘losers’ being found on the ‘margins’ of society – unemployed, immigrants, unqualified workers, precarious employees, small farmers or struggling small businesses. Like elsewhere in the world, the structure of the economy has been profoundly modified over the past 30-40 years, with the dominance of the tertiary sector (services and commerce) and the decline of primary and secondary industries.

Politically, Mitterrand’s election in 1981 brought the left to power for the first time under the Fifth Republic (the fabled alternance) but quickly brought disillusion, disappointment and disenchantment on the left, which got a rude awakening. The PS abandoned utopian dreams of changer la vie (change life) and became a ‘party of government’, adapted and conditioned to the harsh realities and constraints of governing. The left and right became more similar, almost indistinguishable – “the same lot” – in the eyes of many voters, particularly those who voted for Le Pen. Quickly, particularly after the first cohabitation (Mitterrand/Chirac 1986-1988) or the right’s return to the Élysée (1995), both the mainstream left and right were held equally responsible for the country’s problems. Many grew disillusioned with both left and right and their voting habits significantly more volatile and unpredictable than in the past – the ‘floating voters’ or ‘protest voters’.

In 1984, the FN attracted a fairly well-off right-wing electorate radicalized by the mainstream right’s defeat in 1981, the participation of Communist ministers in the government (until 1984) and a growing (permanent) immigrant population in large urban areas (Mitterrand had also legalized all illegal immigrants and his 1981 platform had promised local voting rights for foreigners). A good number of the FN’s 1984 voters (a third) – predominantly the right-wing bourgeoisie who had wanted to send a message in the unimportant second-order EP elections – did not repeat their vote in 1986, but they were replaced by new voters. Beginning in 1986, without ever losing a strong ‘dogmatic’ ideologically far-right base, the FN’s electorate gradually ‘proletarianized’ – attracting a more working-class, blue-collar electorate as well as many ‘floating/protest voters’ (the two go together). In the 1970s, around 70% of manual workers (ouvriers) supported the left (PS and PCF), a number which declined to about 60% in the first round of the 1988 presidential election and 45% in 1995 (including the far-left). but the class cleavage was always weaker in France than in Scandinavia or Britain (because of the religious cleavage), leaving a non-negligible 30% of ‘right-wing (Catholic) ouvriers‘. Le Pen began by gaining these ‘right-wing ouvriers‘ in the 1980s.

The right enjoys blaming François Mitterrand for “encouraging” the rise of the FN in the 1980s. In 1982, Mitterrand intervened to give a larger media presence to Le Pen, who had complained to the president about the lack of media coverage for the FN. Beginning in 1982, Le Pen began appearing in the media (radio and television interviews and appearances) and, by late 1983/early 1984, he was a regular guest on the nightly news or high-audience radio and television programs. His February 1984 appearance on L’heure de vérité on Antenne 2 is remembered as his media ‘breakthrough’. Le Pen became a media star and quickly understood how to use and exploit the media to suit his political needs – seeking the attention and controversy while simultaneously attacking the media and complaining of its bias against him.

Combined with the switch to proportional representation for the 1986 legislative elections, the sly and masterful Mitterrand tried to use Le Pen to take votes away from the right while discrediting it by pushing it to associate with Le Pen’s controversial opinions. However, the monster he had created soon escaped him…

The FN has, since the 1980s, always presented the mainstream right with a bothersome moral dilemma or political nightmare: what attitude, and political strategy, should the right adopt towards the far-right? Should the FN be shunned as a beyond-the-pale far-right which does not conform to basic ‘republican values’, or should the FN be accepted – at some distance – as a party like any other and potential partner?

In the 1983 municipal by-election in Dreux, one of the key ‘steps’ in the FN’s emergence, the RPR-UDF list merged with Stirbois’ FN list (which won 17%) and the right-FN alliance won in the runoff – with the FN associated to the right in the city’s government until 1989. At the time, most of the right’s national leaders – including Jacques Chirac, Alain Juppé and Jean-Claude Gaudin – supported and justified the alliance, often on the basis of the socialo-communiste threat. In the 1986 regional elections, the right tactically allied with the FN to win the presidencies of 6 regions and the far-right was even represented by vice-presidents in four regional executives (including two vice-presidents in PACA, presided by Jean-Claude Gaudin, now mayor of Marseille).

Chirac is alleged to have met with Le Pen in between the two rounds of the 1988 election (they had already crossed paths while on vacation in 1987), said to have been arranged through Charles Pasqua. Nevertheless, Chirac proved intransigent and inflexible and both men hate one another since then. In the 1988 legislative election, the FN and the right agreed to reciprocal withdrawals in the Bouches-du-Rhône and Var – with the right withdrawing from the runoffs where the FN had surpassed the right in the first round. Only one FN deputy was elected as a result of the right’s withdrawal: Yann Piat, who was excluded from the party in October 1988 and assassinated in 1994. 1988 marked the end of formal or de facto electoral alliances between the right and the FN, which were officially condemned by the national leaderships of the right-wing parties in 1991.

Nevertheless, given that the electoral system used for regional elections until 2004 (single-round list PR with no majority bonus) did not produce stable absolute majorities, the right accepted FN regional councillors’ votes to win the regional presidencies in 3 regions in 1992 (UDF dissident Jean-Pierre Soisson, a cabinet minister during Mitterrand’s second term, was elected in Burgundy with a left-Greens-FN alliance which lasted a year). In 1998, with the FN stronger and the left and right more evenly matched, many regions appeared ungovernable. Three UDF presidents were elected after accepting FN votes (a fourth, Charles Millon in Rhône-Alpes, had his election invalidated), all were excluded from the UDF and led to the split of the UDF’s liberal party, Démocratie libérale (DL) led by Alain Madelin. In six regions, however, the RPR-UDF refused alliances with the FN and let the left take control. After 1998, alliances of any sort became even rarer, and the right accepted – in large part – the ‘republican front’ (front républicain) against the far-right.

The discourse(s)

Jean-Marie Le Pen’s FN was a populist protest party, opportunistically changing or adapting its discourse with the times. The early FN, up until the mid-1980s, was an explicitly right-wing nationalist-conservative party: viscerally anti-communist and economically liberal. It attacked the ‘plethoric state’, the welfare state, excessive bureaucracy and the heavy tax burden while offering simple answers: less bureaucracy, a state focused on its core responsibilities and lower taxes (abolition of income taxes). In 1974, Le Pen claimed to be the only right-wing candidate, while in the 1980s he professed his admiration for Ronald Reagan – and positioned the FN as the most pro-American (Atlanticist) party in France. The FN’s neoliberal populism made it similar to the early Progress parties in Denmark and Norway. In the 1980s, the FN primarily attracted a right-wing petit bourgeois electorate of self-employed shopkeepers, small businessmen and some manual workers and white-collar professionals.

In the 1980s, immigration and security, hitherto secondary to anti-communism, became the FN’s core issues. Immigration had increased rapidly in the post-war era, but the proportion of foreigners and immigrants in France has remained relatively stable since the 1970s. What changed, however, was the type and origins of immigrants. Until the 1970s, immigration was intended to fill labour shortages and immigrants were mostly working-age males who came from other European countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, eastern Europe) and to a lesser extent from France’s North African colonies. With the oil crises of the 1970s and growing unemployment, the government restricted labour migration, but facilitated family reunification. Since the 1970s, immigrants are younger women and men who come primarily from North African, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Whereas in 1962, 79% of immigrants were of European origin (primarily Italian and Spanish), by 1990, only half of immigrants were of European origin. In 2014, 36% of immigrants were born in Europe compared to 44% in Africa and 14.5% in Asia. The changing face of immigration coincided with the onset of prolonged periods of economic stagnation or difficulties, rising unemployment (644,000 unemployed in 1975, 2.1 million in 1988), deindustrialization and new social problems (crime, drugs).

The FN quickly tied immigration to unemployment and crime, with slogans like “3 million unemployed is 3 million immigrants too many”. “National preference” (préférence nationale) – reserving access to or giving priority for jobs, benefits and housing to French nationals – became the cornerstone of the FN’s platform beginning in the mid-1980s and provided the party’s answer to all major socioeconomic problems (unemployment, social benefits, housing, social security). The FN’s other two simplistic populist ‘solutions’ were expelling all ‘third world’ immigrants/stopping immigration and reestablishing the death penalty (through a ‘popular initiative referendum’). Immigration and insecurity/crime were by far the major issues for Le Pen/FN voters in successive elections, and personal attitudes towards immigration or ethnocentrism became, by far, the strongest determinants of support for the far-right. This has remained true to this day.

Moreover, Le Pen gained ‘control’ of the immigration issue, with polls since the 1980s indicating that about 30% of voters shared Le Pen’s views on immigration (and thematically related issues like security). In addition, agreement with ‘FN-like statements’ including “there are too many immigrants in France” (69% in 1988, 75% in 1995, 55% in 2002, 48% in 2007) or reestablishment of the death penalty (36% in 2007) far surpassed support for the far-right. By making immigration his niche, Le Pen began effectively setting the agenda on the topic and made it a major issue in the political debate. Few politicians on either the mainstream left or right assertively challenged him on immigration, but many tried to imitate him. The spread of Le Pen’s views, the lepénisation des esprits, instead led the left and especially the right to adopt increasingly hardline policies on immigration or at least ‘talk tough’, sometimes in FN-lite terms, about the topic. One of the most famous examples was Jacques Chirac’s 1991 comment about the “noise and the smell” (le bruit et l’odeur) of immigrants.

Jean-Marie Le Pen likely never truly aspired to win power: he relished his role as the perennial opponent and provocateur, stacking up protest votes. Le Pen enjoyed provoking his opponents – and getting media attention – with incendiary racist, anti-Semitic, homophobic or otherwise crassly inappropriate statements and outbursts, because even if they only made him more repugnant to a majority of voters, all publicity is good publicity and his base came to enjoy (or at least tolerate) his rebellious diatribes against the ‘elites’ and ‘the system’. The list of Le Pen’s most famous provocations is very long: Nazi gas chambers as a “point of detail” of World War II (1987, reiterated in 1997, 2008 and 2009), the bad pun Durafour-crématoire (1988, play on words with Michel Durafour, a centrist minister and ‘crematory oven’), the German occupation of France not being particularly inhumane (2005) or the ‘obvious’ inequality of races (1996). After each firestorm and the quasi-unanimous indignation, Le Pen could claim that he was the only one telling the ‘troubling truths’ or that he was ‘muzzled’ for telling the truth.

From the neoliberal populist and ‘openly’ right-wing FN of the early years, the party somewhat downplayed ideological references to the right and doubled down on its catch-all protest character – without ever, of course, dropping the focus on its recognized ‘niche issues’ like immigration or even its anti-tax attitudes. In the 1990s, the FN began attacking ‘globalism’ (globalization and free trade) while it moved towards protectionism, interventionism and protection of the welfare state (from ‘globalism’ and foreigners/immigrants). Inspired by his son-in-law (and party cadre) Samuel Maréchal, Le Pen dropped the FN’s references to the right and positioned himself as ‘neither right nor left’ (ni droite ni gauche) – anti-establishment. He virulently denounced the bande des quatre (gang of four) – the PCF, PS, UDF and RPR – as the four parties complicit in the ‘decadence’ and ‘decline’ of France (in the 1980s, he had already denounced the RPR and UDF, but as ‘centre-left’ parties defrauding right-wing voters). His discourse in the 1990s became tailored towards the FN’s growing working-class electorate, which often lacked ideological references to the right and felt abandoned by all parties.

In the 1995 presidential election, Le Pen won about 25% of the vote among manual workers and made strong gains in the industrialized northeastern quadrant of the country, strongly correlating with the PS’ losses. Political scientist Pascal Perrineau coined the term “gaucho-lepénisme” after Le Pen’s ‘breakthrough’ with the formerly left-wing working-class in 1995, referring to three types of voters: formerly left-wing voters switching to the FN, voters still identifying with the left but voting FN or ‘transient’ FN protest voters who still support the left in a runoff. Gaucho-lepénisme has been the subject of academic debate since the 1990s, but the term became very popular with the media, always looking for a deceptively simple way to describe complicated things.

The 1998-1999 split

The FN’s inexorable rise appeared to have been suddenly halted by a major internal split – or ‘putsch’, as Le Pen calls it – in December 1998, when Bruno Mégret and his followers left the party and founded what became the Mouvement national républicain (National Republican Movement, MNR). In the 1999 EP elections, the divided far-right was reduced to 5.7% for the FN and 3.3% for Mégret’s MNR; in the 2001 municipal elections, both far-right parties did poorly.

Bruno Mégret was a graduate of the highly prestigious École polytechnique and a senior technocrat who had been a member of the RPR and the right-wing reflection group Club de l’horloge. The Club de l’horloge was a national-liberal (nationalist and economically liberal) group wishing to bridge the right and the FN and ‘unite the right’ against the socialist-communist threat. Its leading members were, like Mégret, mostly upper-class technocrats and graduates of elite schools (ENA, Polytechnique). Mégret quit the RPR in 1982 and created his own movement, the ‘republican action committees’, which would serve as his platform to ally with and later join the FN. He was one of the 35 deputies elected with the FN in the 1986 legislative elections, and was elected to the European Parliament – the traditional refuge for FN politicians – in 1989 and 1994.

A talented organizer, strategist and ideologist, Mégret pushed his way up the ranks, becoming general delegate in 1988 – effectively the party’s ‘number two’ after his rival Jean-Pierre Stirbois’ death – and the FN leader in the Bouches-du-Rhône and the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (PACA) region. Mégret’s ambitions annoyed and worried Le Pen, who never tolerated any real challenge to his leadership. But the two also differed on the party’s direction and electoral strategy. As explained above, Le Pen relished his role as the provocateur and eternal opponent and seemingly never really aspired to actually win power. Mégret, beginning at the FN’s 1990 congress, wanted to make the FN a respectable and credible alternative and potential governing party, in alliance with the mainstream right (but with the FN in command), which implied moderating or euphemizing the party’s discourse. Having come from the right and having joined the FN in good part because he found the RPR insufficiently anti-socialist, Mégret was more ideological than Le Pen, closer to the right-wing neoliberal populism of the early years than Samuel Maréchal’s ni-ni.

By the late 1990s, Mégret realized that Le Pen had no interest in making the FN more respectable or controlling his intentional slip-ups – instead, Le Pen continuously outdid himself with controversial ‘politically incorrect’ statements. Le Pen, meanwhile, saw Mégret as an ambitious rival who threatened his control of the family enterprise, particularly after the FN’s 1997 congress, in which the mégretistes performed well in elections for the party’s central committee. The detonator was a dispute over the top candidacy for the 1999 EP elections, which Mégret felt was legitimately his, but he was passed over in the summer of 1998 in favour of Le Pen’s wife Jany.

Mégret and his allies quit the party in December 1998, with the splinter party eventually taking the name MNR after failing to take the FN brand for itself. Mégret took a majority of regional councillors and departmental secretaries and a substantial minority of Politburo and central committee members with him. The mégretiste dissidents included Mégret’s wife Catherine, elected mayor of Vitrolles (Bouches-du-Rhône) in 1997, and some of Mégret’s old colleagues from the Club de l’horloge, like Jean-Yves Le Gallou, a former member of the GRECE close to the ‘identitarian’ (white supremacist) and ethno-differentialist (neo-racist) movements. By his ideology and political strategy, Mégret was closer to the ideologues of the Nouvelle Droite or the ‘nationalist-revolutionary’ movements. Most ‘nationalist-revolutionary’ groups like the GUD or Unité Radicale sympathized with the MNR, and the party’s ranks initially included people like Le Gallou and Pierre Vial (leader of the white supremacist, neo-pagan and neo-fascist Terre et peuple movement). Despite the MNR’s association with the far-right fringe (broken and denounced by 2002), it aspired to be the ‘credible’ right-wing nationalist alternative and a potential alliance partner for the mainstream right. In the 2002 presidential election, Mégret – like Le Pen in 1974 – claimed to be the only right-wing candidate.

The MNR, however, proved to be a massive failure: it only managed to briefly weaken the far-right between 1999 and 2001, and it never surpassed the FN in any national election – nor did it, for that matter, ever win over 3.5% in a national election (3.3% in 1999). In 2002, Jean-Marie Le Pen won 16.9% of the vote in the first round of the presidential election, placing second and qualifying for the runoff ahead of incumbent prime minister and PS candidate Lionel Jospin. Mégret, with an ‘anti-Islamization’ campaign bordering on blatant racism, finished twelfth out of sixteen candidates with only 2.3% of the vote. The MNR fizzled out soon thereafter, and Mégret finally quit politics in 2008.

Mégret may have taken many of the cadres and elected officials, but Le Pen had the name and the FN brand for him. As he liked to repeat, voters preferred “the original over the copy” – crucially, the protest voters – a large chunk of the far-right’s electorate in 2002 – preferred Le Pen. Mégret’s confusing posturing was incomprehensible and unappealing to the bulk of them: seeking to be a ‘credible’ explicitly right-wing nationalist choice, but with a fairly crude and caricatural ‘anti-Islamization’ rhetoric and palling around with repulsive far-right fringe elements. On top of that, he obviously lacked Le Pen’s notoriety and media standing.

However, in arguing that Jean-Marie Le Pen was too extremist in form and discourse and the party by consequence too disreputable to win power, Mégret was in part a precursor of Marine Le Pen’s post-2011 dédiabolisation strategy.

The final years of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s FN

![Presidential 2002 - Le Pen [R1]](https://welections.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/presidential-2002-le-pen-r1.png?w=420&h=325)

% vote for Le Pen, 2002 (first round) (own map)

April 21, 2002 marked the cenit of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s FN. With 16.86% and 4.8 million votes, Jean-Marie Le Pen won his best personal result in a presidential election and – most importantly – placed second, ahead of the PS. The result was entirely unexpected: he was in third place in all polls, no higher than 14%, and the election seemed to inevitably heading towards an unexciting (and somewhat dreaded) Chirac/Jospin runoff. The enormous surprise and shock of the result made headlines around the world at the time and remains an historic moment of French political history – and a traumatic moment for the left.

Le Pen gained over 233,000 votes and 1.9% on his 1995 result – notable, though not massive, gains. He expanded his electorate, particularly in regions where he had traditionally been weaker and with typically right-wing demographics like farmers or retirees. Le Pen’s qualification, however, owed far more to widespread vote splitting, which reached near-absurd levels on the left: Jospin (16.2%) was penalized by the strong performance of the far-left (10% between 3 candidates) and his former coalition partners (Chevènement 5.3%; Mamère for the Greens 5.3%; Hue for the PCF 3.4%; Taubira for the PRG 2.3%). If, for example, only Taubira had not run and all her voters had supported Jospin, he would have qualified with 18.5%. The ‘plural left’ split five ways won 32.5% together. The election was boring and insipid, and first round turnout was lower than ever (71.6%), particularly low in the Parisian region where the election coincided with school vacations.

Jacques Chirac, the fairly unpopular incumbent dogged by corruption scandals and pesky judges, chose to make the election about crime and ‘insecurity’, an issue which, by the way it is usually framed, is difficult for the left. However, Le Pen had some credibility and sway on the topic, one which was already one of the major issues for the far-right electorate. Three-quarters of voters said that insecurity was one the three issues which most influenced their vote.

As much as the first round had been a success for Le Pen, the second round showed the limits to the party’s momentum. The second round quickly became a referendum on Le Pen – and given that over 70% of voters, left and right, disliked him, that was bad news for the far-right. Over a million protesters flooded the streets of France’s major cities, rejecting the racism and extremism embodied by the FN candidate – although many of the protesters, young and left-leaning, were not susceptible of ever voting FN anyway. Jacques Chirac, who had personally hated Le Pen since the 1980s, played the role of the unifier and last bulwark against ‘fascism’. Le Pen’s raw populist appeals to ‘the common people’ (vous les petits, les sans-grade, les exclus) or ‘the miners, metalworkers and workers of all industries ruined by the Euro-globalism of Maastricht’ fell flat. Everybody who hated Le Pen – the vast majority of France in 2002 – voted Chirac without hesitation, though often without enthusiasm. Chirac won a landslide of historic proportions: 82.2% of the vote with 79.7% turnout, with 25.5 million votes against only 5.5 for Jean-Marie Le Pen (17.8%). Le Pen’s raw vote result was barely above that of the sum of his and Mégret’s first round votes; his percentage was below that of the far-right on April 21 (19.2%).

The FN’s momentum broken by the runoff, the party managed only 11.1% in the June 2002 legislative elections, a sizable loss compared to 1997. The party won no seats. In the 2004 European, cantonal and regional elections, the FN’s results were middling: 12.1% in the cantonal elections, 14.7% in the regional elections and 9.8% in the EP elections. The FN remained a sizable force in French politics, but appeared to be a distant third behind the right and left with no real chance at winning. The FN naturally supported the victorious ‘No’ option in the 2005 referendum, with heavily nationalist arguments (against immigration, Turkish membership etc.), but that success was obviously ‘shared’ with other Eurosceptic/anti-EU right-wing forces (Philippe de Villiers, Charles Pasqua) and the left.

% change in Le Pen vote, 2002-2007 (source: F. Salmon)

For his 2007 campaign, Le Pen, pushed and guided by his daughter Marine Le Pen, sought to adopt a more ‘consensual’ and ‘modern’ image. But you can’t change old habits in a septuagenarian (at the time). Le Pen faced strong competition from the UMP’s candidate, Nicolas Sarkozy, who went after Le Pen’s 2002 voters with tough rhetoric on ‘controlling immigration’ and ‘law and order’. Whereas Chirac, after the early 1990s, had more or less given up on winning back FN voters – his 1995 campaign was more ‘left-wing’ with la fracture sociale – Sarkozy’s strategy was to win by expanding on his right (while neglecting the centre a bit). His strategy was very successful: in the first round, Le Pen won only 10.4% – this time, polls had overestimated him (14%) and Sarkozy won 31.2% (a very strong first round result: Chirac won only 19.9% in 2002). Between a fifth and a third of Le Pen’s 2002 electorate voted for Sarkozy in the first round.

Sarkozy, as interior minister (2002-2004, 2005-2007), constructed an image and reputation as being firm and a ‘doer’ focused on criminality (particularly youth delinquency) and on limiting immigration. While Chirac and his prime ministers (Jean-Pierre Raffarin and Dominique de Villepin) became very unpopular in part because of a widespread perception that they ‘did nothing’ and/or lacked the courage to ‘do what needed to be done’, Sarkozy’s active presence on the ground as interior minister and his ability to translate (some) words into deeds was appreciated by a majority of voters, including FN supporters. Sarkozy did not mince words: during the 2005 banlieue riots, he famously vowed to ‘clean the cités with Kärcher’ or referring to rioters as voyous and racaille (thugs, scum) – criticized by the left as stigmatizing or lepéniste rhetoric, his words only contributed to his reputation as a no-nonsense doer and reinforced his popularity on the right. To Le Pen voters who switched to Sarkozy in April 2007, Sarkozy offered many of the same ideas on immigration or crime as Le Pen – but with the added advantage of credibility, respectability and a more measured and moderate outlook (he was also younger and more dynamic). And he had a realistic chance of winning power and actually doing what he proposed – unlike Le Pen, who never had a chance of winning.

Relatively few of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s supporters voted for him because they shared all of his political views or because they felt that he would make the best president: in 2002, only 18% of Le Pen’s voters said that they voted for him because they trusted him and only 9% said that they supported him because he had ‘the stature of a president’. In 1997, 84% of those who had voted FN at least once in the past said they had done so out of rejection of the other parties rather than because of identification with the FN. This Ifop analysis from 2007 includes interviews with Le Pen 2002-Sarkozy 2007 switchers which underline several overarching themes: Sarkozy was credible (including on other issues), respectable, younger, more moderate, less dangerous, more serious, had a chance of winning and they liked his record.

The Le Pen 2002 voters who switched to Sarkozy in April 2007 were primarily from the less anti-establishment and more middle-class segment of the heterogeneous FN coalition, while those who stuck with Le Pen in 2007 were both solid core FN sympathizers (ideologically loyal to the far-right) and hardline anti-establishment, more working-class voters. Therefore, Le Pen’s 2007 electorate was significantly more blue-collar and ‘proletarian’ than his 2002 or even 1995 electorate – a trend which would be reinforced under his daughter, in 2012 and later.

After the poor result in the presidential election, the FN did even worse in the low-turnout legislative election which ensued – it won only 4.3% of the vote nationally, a loss of over 7% from 2002. It did no better in the 2008 municipal and cantonal elections, in which the party struggled to run lists or candidates in many places and won poor results where it did (4.9% in the cantonal elections). In the 2009 EP elections, the FN did slightly better – 6.3% – which was just enough for the party to save three seats for its three most prominent figures: Jean-Marie and Marine Le Pen and Bruno Gollnisch. The party faced financial difficulties and was forced to sell its headquarters (le Paquebot) in the chic Parisian suburb of Saint-Cloud and move to a cheaper HQ in less glamorous Nanterre.

The party turned the corner at the 2010 regional elections, in which it did unexpectedly (relatively) well, with 11.4% nationally in the first round and qualified for the runoff in 12 regions. The FN even improved its showing in the triangulaire runoffs, which is unusual: Jean-Marie Le Pen won 23% in PACA and Marine Le Pen won 22% in Nord-Pas-de-Calais. One of the reasons for the FN’s resurgence beginning in 2010 was Le Pen’s daughter and heir apparent, Marine Le Pen.

Marine Le Pen

In April 2010, Jean-Marie Le Pen announced he would leave the party’s leadership at the next congress (January 2011) and that he would not run in 2012. His youngest daughter, Marine Le Pen, was the heir apparent.

From unlikely to anointed successor

Marine Le Pen, born in 1968, is the youngest of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s three daughters with his first wife, Pierrette Lalanne (m. 1960-d. 1987). She spent the latter years of her childhood in the family mansion of Montretout in upscale Saint-Cloud, which her father inherited in 1976 from wealthy far-right businessman Hubert Lambert. She moved out of the family property in 2014, after one of her Bengal cats was killed by one of her father’s doberman.

Marine went to law school (Paris II) and became a lawyer with the Paris bar in 1992. Her professional career was very brief: her only ‘big’ case was the contaminated blood scandal, and she resigned from the bar in January 1998 to join the FN’s legal services. Her father lived for politics, so she was somewhat naturally brought to the family business out of family solidarity – in part from the stigmatization she experienced in university from her family name. She became close friends with members of the GUD (Groupe union défense), a violent far-right student organization, like Frédéric Chatillon and Philippe Péninque.

Her rise in the FN was, at first, slow and behind the scenes: she ran, more as a paper candidate than anything, in a Parisian constituency in the 1993 legislative elections and won 11%, and she was elected regional councillor in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais in 1998. Aligned with the anti-Mégret faction of the party and prodded by her brother-in-law Samuel Maréchal, Marine Le Pen unsuccessfully ran for the party’s central committee at the 1997 congress, but she was nevertheless later appointed to it by her father.

It is likely that Marine Le Pen was not her father’s initial ‘preferred successor’, although the family has shoo-shooed such claims. Le Pen’s oldest daughter, Marie-Caroline Le Pen (b. 1960), politically active at her father’s side since 1975, originally appeared to be the preferred daughter – but she joined Mégret’s MNR with her husband, Philippe Olivier, at the 1998 split and moved out of the family residence in Saint-Cloud (and didn’t speak to her father again). Marine Le Pen’s own rise to power began after the Mégret ‘putsch’.

Her public political breakthrough began with the 2002 campaign, where she served on the ‘ideas-image’ team, working to ‘polish’ Le Pen’s image and present him as an experienced rather than angry old man. Her first TV appearance on the night of the runoff got her noticed by the media and the public, and she would become a regular fixture in the media in the coming years. In the 2002 legislative elections in the Pas-de-Calais’ 13th constituency (Lens), she won a good result (24% in the first round, 32% in the runoff against the PS).

Between 2002 and 2007, she became one of the major figures in the party and the main rival of Bruno Gollnisch, the other likely successor. Marine Le Pen already signalled her intentions to modernize and revamp the party’s image, with more moderate and relaxed attitudes on issues like abortion and a substantially more polished and respectable public appearance. Her ideas and rapid ascent bothered many of the FN’s old cadres. She failed to win reelection to the central committee at the 2003 congress, but she was again saved by saved by daddy, who named her one of the party vice presidents. In 2005, she took a leave from party duties and temporarily moved out of the house after her father’s controversial comments on the German occupation (‘not particularly inhumane’).

In 2004, Marine Le Pen tried to build an electoral base in Île-de-France – running as the party’s top regional candidate in the regional and EP elections that year. In the March 2004 regional elections, her list won 12.3% in the first round and 10.1% in the runoff, a result judged disappointing by commentators at the time. In the EP elections, her list won 8.6% and a single seat (hers). Given the poor results obtained, her attempt at carving out her electoral base in the Paris region was a failure.

She took her ideas on modernizing and improving the party’ to her father’s 2007 presidential campaign (she was strategic director). Among other things, she was behind an unusual ad campaign which included (among others) a young North African woman giving a thumbs down to illustrate the ‘failure’ of left and right on several issues (nationality, assimilation, social mobility, secularism). After Le Pen’s poor result in 2007 (10.4%), Marine’s internal opponents accused her of having distanced the party from its roots and following a futile strategy. Nevertheless, running the Pas-de-Calais’ 14th constituency (Hénin-Beaumont), Marine Le Pen was the party’s only bright spot in an otherwise disastrous election in June 2007. She won 24.5% in the first round and 41.7% in the runoff against PS incumbent Albert Facon – she was the only FN candidate in the country to qualify for the second round in 2007.

Beginning in 2007, Marine Le Pen made Hénin-Beaumont, a former coal mining town in the Pas-de-Calais mining basin, her new political base. The city (pop. 26,400) was more electorally lucrative than Île-de-France and had all the ingredients to make it a frontiste stronghold. As a former coal mining town, it has high unemployment, low incomes, lower levels of education and a weak economic base. It also had specific local political circumstances which made it ripe for picking by the FN. A Socialist stronghold since 1953, recent local administrations (under then-mayor Gérard Dalongeville) had left behind a ballooning debt, rising taxes, corruption and mismanagement – conditions which fit perfectly with the FN’s “a pox on both your houses” rhetoric. She also benefited from over a decade of local grassroots work by the FN’s local boss, Steeve Briois (a former mégretiste pardoned for his sins) – a municipal councillor since 1995. Marine Le Pen had no personal or business ties to the region, but ‘electoral tourism’ – seeking election in favourable regions – is a common and necessary practice in the FN since the 1980s. In 2009, Marine Le Pen was reelected to the European Parliament from the Nord-Ouest Euroconstituency, which includes the Nord-Pas-de-Calais.

In the 2008 municipal elections, with Marine second on Briois’ list, the FN won 28.5% in the first round (second) and 28.8% in a triangulaire runoff, a disappointing showing for the party which finished only a distant second behind incumbent PS mayor Gérard Dalongeville. The FN, however, got a second chance after Dalongeville was arrested and removed from office for embezzlement, sparking a local by-election in 2009. In the first round, the FN – with Marine second on the list – placed first against a divided left with 39.3%. The risk of a FN victory in the second round prompted a front républicain behind left-wing independent Daniel Duquenne – who received endorsements from the rest of the left (PS, PCF, Greens), the right (UMP-NC) and civil society (actor Dany Boon) to defeat the FN. The FN was narrowly defeated in the second round, but won 47.6% of the vote and was within 550 votes of victory. In 2010, Marine Le Pen was the FN’s candidate in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais in the regional elections and won the party’s second best result in the runoff (22.2%), behind her father in PACA.

By 2010-2011, Marine Le Pen was the runaway favourite to succeed her father at the helm of the party, with daddy’s blessing. Her rapid rise to power and her ideas to ‘change’ the party unsettled and annoyed the ‘old guard’ of the party – the old-timers and Jean-Marie Le Pen loyalists. Considering that she was unstoppable, many of her internal rivals left the FN before she even became leader. The first to leave was Carl Lang, a three-term MEP (1994-2009) and former party secretary general (1999-2005), whose place as FN leader in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais (where he was regional councillor since 1998) was ‘usurped’ by Marine Le Pen in 2009. He created a dissident party of his own, the Parti de la France (PDF), which was joined by a significant number of other prominent (and somewhat famous) old guard figures from the FN: Christian and Myriam Baeckeroot, Martine Lehideux (widow of André Dufraisse, a Nazi collaborator who fought on the Eastern Front with the LVF), Fernand Le Rachinel (a printer and one of the FN’s major creditors/financiers who later sued the party to get his money back), and, briefly, Bernard Antony (from the traditionalist Catholic faction of the FN). The PDF, despite attracting a fair number of historic figures of the far-right, had very minimal electoral support and quickly declined into utter irrelevancy. In the 2009 EP elections, the PDF and allies (dissident MEP Jean-Claude Martinez) won 0.5% (1.4% where they ran); in the 2010 regional elections, the non-FN far-right (mostly PDF) won 0.9% while in the 2012 legislative elections, the PDF and assorted anti-FN far-right parties (MNR, Ligue du Sud…) only ran 65 candidates and won 0.5% nationally.

The far-right niche media – Minute, Rivarol and Présent – also opposed Marine Le Pen, considered too soft and insufficiently dogmatic.

Marine Le Pen’s rival for the party leadership at the January 2011 Tours congress was Bruno Gollnisch. Gollnisch, a loyal Le Pen ally since the 1980s (deputy 1986-88, MEP since 1989), was the candidate of the more radical and ‘traditionalist’ old guard which didn’t see much warranting change in the party’s strategy and rhetoric. Despite perhaps a greater ideological proximity to the outgoing patriarch, Gollnisch did not stand a chance: besides the fact that most of Marine’s opponents had already left the party, he had a massive notoriety and image deficit compared to Marine Le Pen. Marine was a well-known figure, charismatic, telegenic and media savvy. She struck the ‘right balance’ between pleasing the base (in 2010, she compared street prayers to a military occupation) and reassuring the general public that she would ‘clean up’ the party (opposing the presence of “radical, caricatural and anachronistic groups” in the FN – ‘fundamentalist Catholics, pétainistes and those obsessed with the Holocaust’ – and warned that the FN wouldn’t serve “as a sounding board for their obsessions”). Gollnisch, in contrast, was not as well known, seldom appearing in the media and – to those who did know him – seen as dogmatic and radical, with public ties to unsavoury far-right radical groups in France and abroad (like Jobbik in Hungary or the white supremacist American Renaissance magazine) and a history of controversial statements about the Holocaust (questioning the number of deaths and the existence of gas chambers). Gollnisch did retain strong support among FN cadres and members – in 2007, he had placed first, ahead of Marine Le Pen, in the elections to the central committee.

Marine Le Pen was elected FN president at the Tours congress with 67.65% of the vote against 32.35% for Bruno Gollnisch, with about 17,000 members out of 22,400 dues-paying members participating. A number of Gollnisch’s remaining supporters within the party would either leave out of their own volition (Roger Holeindre, an old guard Jean-Marie Le Pen loyalist) or be excluded (Yvan Benedetti and Alexandre Gabriac, members of the extremist pétainiste Œuvre française).

Dédiabolisation: Reality or smokescreen?

Since taking over the party, Marine Le Pen’s core strategy has been the dédiabolisation (‘undemonization’) of the FN. Her goal, in short, has been to make the FN palatable to a wider range of voters by adopting a smoothed, more nuanced and euphemized discourse rid of her father’s provocations or outrageous statements.

One of the main aspects of dédiabolisation is drawing a contrast between past (J-M Le Pen) and present (Marine) to bring out the differences. She has played heavily on her gender (nice, calm and smiling vs. the bitter and angry old man) and relative youth (no connection to World War II or the old circles of the post-war far-right) to reinforce the modernized and ‘humanized’ new face of the party. Marine Le Pen is a ‘modern woman’ – twice divorced with three kids (who she raised on her own), currently unmarried and described as having been a ‘partier’ in university – and has a more appealing image than her father – war veteran, blind in one eye (with a distinctive pirate eye patch in the 1970s) and with a long record of disturbing comments.

The priority of dédiabolisation was anti-Semitism – indeed, as Louis Aliot (Marine’s partner and party vice president ) said, dédiabolisation was limited to anti-Semitism. Annual studies by France’s consultative commission on human rights (CNCDH) have shown that Jews are the least stigmatized religious minority in France, although some stereotypes and prejudices remain fairly widespread (mostly those related to money), so the perception of the FN as anti-Semitic was one of the most problematic aspects of the party’s image. Marine Le Pen has repeatedly repudiated her father’s most controversial statements on the Holocaust – in February 2011, shortly after being elected, she told Le Point that concentration camps were the “epitome of barbarism”, quickly settling the debate about her personal views and distancing ‘her party’ from that of her father.

Dédiabolisation has implied changes or recasts of certain aspects of the party’s platform. On economic issues, Marine Le Pen dropped almost all remaining hints of the FN’s early neoliberal populism in favour of protectionism and interventionism, with the core ideas being withdrawal from the Eurozone, defence of public services, opposition to free trade and globalization (globalism) and increased spending in certain fields (including welfare benefits). The FN had been moving in that direction since the 1990s, but Marine Le Pen accentuated it and put more emphasis on le social (socioeconomic issues).

The early FN was a very socially conservative party (anti-abortion) and Jean-Marie Le Pen was rather homophobic, but Marine Le Pen has claimed that she is pro-choice and has tried to make the party appear more socially liberal or at least more ‘modern’ on social/moral issues, in a country where the appetite for social conservatism is small. Nevertheless, social issues divide the party – which retains a strong and influential conservative pro-life and anti-gay marriage Catholic base – and the FN has wanted, incoherently, to conciliate both its old socially conservative factions and appeal to a wider public. For example, Marine Le Pen opposed the legalization of same-sex marriage and adoption in 2013, but she never participated in the demonstrations against the bill (Manif pour tous), although several high-ranking members of the party did (alongside Nick Griffin…).

On immigration, the essence hasn’t changed, but the form in which it is presented has. Notably, analysts have pointed out that Marine Le Pen, compared to her father, has somewhat de-emphasized immigration in favour of ‘Islamization’ or other unrelated issues (economics, trade, sovereignty). The discourse around immigration and Islam is slicker and smoother – more euphemisms, less blatancy. Marine has been careful not to conflate Islam and Islamism/Islamic fundamentalism, claiming that Islam by itself is compatible with France, democracy and the republic; in reality, the supporters don’t differentiate between the two. When catering to the base, however, Marine Le Pen drops the act and insinuates that Muslim immigrants can’t be assimilated. Islamization is presented under the angle of defending laïcité (secularism), a cherished republican value which the far-right had historically opposed. In so doing, Marine Le Pen has linked the issue to a core republican value and shielded herself (somewhat) from being attacked as ‘anti-republican’ (which the FN has typically been seen as being, especially by the left).

Marine Le Pen’s purported ideological references are eclectic, ranging from left to right. Upon her election to the party leadership in 2011, she famously cited French socialist icon Jean Jaurès. In her 2012 book, Pour que vive la France, she paid tribute to the historical left and the programme of the National Council of the Resistance (1944) and cited a wide range of political figures including Pierre Mendès France, Karl Marx, George Orwell, Marie-France Garaud, Thomas Piketty and FDR. For the general public, therefore, she has no apparent connection to the old generations of far-right and nationalist intellectuals (Charles Maurras, Maurice Barrès) or the old circles of the post-war far-right (Occident, Ordre nouveau, GRECE, OAS sympathizers etc.).

Marine Le Pen has also made real efforts to clean up the party and rid it of embarrassing radical elements – neo-fascists, racists, anti-Semites, Nazi apologists and other assorted cranks. She was helped by the fact that most of those milieus didn’t like her to begin with and had either left the party and/or were explicitly in opposition to her. One of the earliest acts of dédiabolisation was the expulsion of regional councillor Alexandre Gabriac in 2011, an obese skinhead, after Le Nouvel Observateur published pictures of him doing the Nazi salute. Jean-Marie Le Pen, in an early sign of his disapproval of his daughter’s strategy, disapproved of Gabriac’s exclusion from the party. A number of other whackos, those most intent on airing their nonsense in public, have also been kicked out the party or suspended (in 2013, a FN candidate compared justice minister Christiane Taubira – who is black – to a monkey, in 2014, a FN candidate had a Nazi flag in her house).

The FN doesn’t want embarrassing members and candidates polluting the party’s sanitized appearance. However, behind closed doors, many FN members and sympathizers have problematic views (at best) or are openly racist, homophobic, Islamophobic, sexist or anti-Semitic. Journalists who ‘infiltrated’ local FN sections (like Claire Checcaglini) or former members who left the party have shown how many FN members and local cadres hold rather appalling views (on race, immigration, religion etc.) – which they are instructed to keep under wraps for the sake of appearances. Election after election, scrutiny of FN candidates’ social media accounts or public statements brings up a lot of candidates – mostly the no-name paper candidates, with no chance at victory (but they may be regional or municipal councillors) – with appalling views and opinions. For example, BuzzFeed’s very thorough scrutiny of the social media accounts of the FN’s 573 candidates in this year’s legislative elections found a whole range of whackjobs: racists, anti-Semites, Islamophoes, conspiracy theorists (chemtrails, ‘great replacement’, paedophile conspiracies), white supremacists, fans of racist cartoons/jokes or ‘likes’ for neo-Nazi or neo-fascist groups. The FN, when confronted with such stories, has more often than not stood behind its candidates (or symbolically punished a handful) and accused the journalists behind the investigations.

Marine Le Pen’s FN has grown close to the identitarian movement, a white supremacist outgrowth of the Nouvelle Droite which opposes ethnic mixing and supports mass deportations. Philippe Vardon and Benoît Loeuillet, the two most prominent members of the identitarian Nissa Rebela party in Nice (Alpes-Maritimes), were elected regional councillors in PACA in 2015. Philippe Vardon is a former skinhead who, among other things, supports Renaud Camus’ great replacement (grand remplacement) theory – the conspiratorial ‘Muslim colonization/takeover of white Christian France’. Benoît Loeuillet was suspended in 2017 for Holocaust denial (‘I don’t think there were that many deaths’).

According to the CNCDH’s annual report on racism, antisemitism and xenophobia: 23% of FN sympathizers (in 2016) agreed that some races were superior to others, 84% admitted some degree of racism (45% of respondents were ‘rather’, ‘a bit’ or ‘not very’ racist), over 90% agree that many immigrants only want to take advantage of social benefits, 81% think that the Roma don’t want to integrate in society and 85% said that Islam was a threat to national identity. Of all parties, FN sympathizers also have the highest percentage of antisemitic opinions and the least positive opinions of words like laïcité, liberty, gender equality, tolerance and diversity. In 2012 as in past elections, the strongest predictor of FN support was the degree of ‘ethnocentrism’ (as measured, on the basis of respondents’ opinions on a number of generic questions, by an ‘ethnocentrism scale’). In 2016, over 85% of FN sympathizers had high scores on the ethnocentrism scale.

Marine Le Pen may have said that she rejects conspiracy theories, but ‘globalism’ – the new villain of the FN – is depicted as a conspiracy: an anonymous monster or idolatrous cult responsible for every problem (Europe, immigration, technocratic arrogance, weakening of the state, elimination of borders). While secularizing and modernizing the contours, has kept the classic markers of the far-right discourse – the Manichean distinction between ‘us’ (good; the patriots) and ‘them’ (evil; globalists, stateless elites, cosmopolitans, transnational capitalism, big money) and messianism (only the heroic Le Pen can save us), all with heavy hyperbole (catastrophic, disastrous, urgency etc.).

Dédiabolisation isn’t anything new – in fact, the FN was founded and Le Pen invited to lead it as an attempt at dédiabolisation by ON! Many of Marine Le Pen’s strategies – respectability of the party to ‘conquer power’, euphemization of the discourse, attracting outside supporters, creating think tanks and forums to increase its intellectual credibility, emphasis on socioeconomic issues, focus on Islamism rather than immigration etc. – had already been proposed by Bruno Mégret and his supporters in the early 1990s. In that sense, it is amusing how Marine Le Pen – despite having entered party politics to oppose Mégret’s faction – is, in part, doing what Mégret wanted to do in 1990. One of the major differences, however, is that Marine Le Pen has followed Samuel Maréchal’s ni droite-ni gauche rather than Mégret’s ‘union of the rights’ – with the high levels of political distrust and the unpopularity of the major governing parties of the left and right, there is a much larger base for the anti-establishment ni droite-ni gauche appeal. Marine Le Pen, at least until 2015, popularized the ‘UMPS’ neologism (merging ‘UMP’ and ‘PS’) and used it as her preferred line of attack against le système.

Dédiabolisation has also entailed new international alliances, again with the objective of making the FN appear more credible and respectable. In 2009, Le Pen father and Gollnisch had organized their foreign allies in the ‘Alliance of European National Movements‘ (AENM) – which included the FN, Jobbik, the BNP, the neo-fascist Italian Fiamma Tricolore, the ‘Strasserite’ Spanish MSR and the Portuguese PNR. In 2011, Marine Le Pen cut ties with the obscure cranky parties of the AENM and allied with more credible right-wing populist parties in Europe – Heinz-Christian Strache’s FPÖ (Austria), Matteo Salvini’s Lega Nord (Italy), Geert Wilders’ PVV (Netherlands) and the Vlaams Belang. All four of these parties are anti-EU/Eurosceptic, anti-Islamist and anti-immigration; all four of these parties remain controversial in their own right, but have substantial popular support in their countries and have, to varying extents, all ‘cleaned up’ a bit. The unpalatable extremist elements of the European far-right galaxy were excluded: Greece’s Golden Dawn, the German NPD, the BNP and Jobbik. In 2015, anchored by the 20 FN MEPs, a far-right group – Europe of Nations and Freedom – was formed in the EP, with the FPÖ, Vlaams Belang, Lega Nord, PVV, Poland’s KNP (rid of the unpalatable Janusz Korwin-Mikke), a UKIP dissident, a lone dissident Romanian and one of the AfD MEPs.

Marine Le Pen has surrounded herself with a new generation of allies and cadres, some drawn from within the FN (like her partner Louis Aliot) and others recruited from the outside (like Florian Philippot). Several members of her inner circle are former mégretistes (MNR) – like Nicolas Bay (FN secretary general) or her Hénin-Beaumont team (Steeve Briois, Bruno Bilde) – which annoys the remaining ‘old guard’ and her father, who haven’t forgiven the ‘traitors’. Since 2014, the FN now has a growing network of local elected officials including Stéphane Ravier (senator, mayor of Marseille’s 7th sector), David Rachline (senator, mayor of Fréjus), Steeve Briois (Hénin-Beaumont), Fabien Engelmann (Hayange) and Julien Sanchez (Beaucaire).

One of the most emblematic figures of dédiabolisation and the ‘new FN’ is Florian Philippot, the party’s current vice president for strategy and communication and seen – until recently – as the party’s ‘number two’. Philippot is a graduate of HEC Paris and the ENA and a former senior civil servant (inspector general of administration) – a professional profile not unlike that of Bruno Mégret. Philippot considers himself to be a Gaullist and is a former chevènementiste who began advising Marine Le Pen using a pseudonym before formally joining the FN in 2011 – seduced by Marine Le Pen’s ni droite ni gauche party line and statist platform. Philippot was, until recently, considered as Marine’s éminence grise and is the FN’s poster child for dédiabolisation – articulate, telegenic, young (35) and an outsider with an unusual bio. Philippot is considered the main figure of the FN’s new ‘national-republican’ faction – which is statist (anti-liberal), adamantly anti-EU and anti-Euro and inspired by ideological traditions foreign to the traditional far-right (Jacobin republicanism, Gaullism, chevènementisme). Unsurprisingly, Philippot is disliked by the more traditional far-right faction(s) of the FN – who are more economically liberal, socially conservative (close to traditionalist Catholic groups) and aren’t opposed to a ‘union of the rights’.

Behind closed doors, Marine Le Pen has a circle of more enigmatic and obscure advisers and supporters – her old friends Frédéric Chatillon, Philippe Péninque and Axel Loustau. All three were members of the GUD, a violent far-right (and anti-Semitic) student organization when they were in university and have made a fortune in the private sector – often in close collaboration with other ex-GUD friends. Chatillon is a businessman who owns a communications agency, Riwal, which provided services to the FN. In 2012, Riwal printed the FN’s leaflets for the presidential campaign, produced the ‘campaign kits’ sold to FN candidates in the legislative elections (for €16,650) and lent €450,000 to the FN’s campaign at the rate of 7%. Chatillon has had close business and financial ties to the Assad regime in Syria since the 1990s and remains one of the main supporters of President Bashar al-Assad in France. Péninque is a tax lawyer (who notably opened former PS budget minister Jérôme Cahuzac’s secret Swiss bank account in the 1990s) who has been a discreet but influential adviser to both Jean-Marie and Marine Le Pen for a decade. Axel Loustau, whose father was a close friend of Jean-Marie Le Pen, is a Riwal shareholder and has a private security company which has complemented the FN’s official private security service in rallies. Loustau is more public: he has been a FN candidate in several elections since the 1990s and was elected regional councillor in Île-de-France in 2015. All three of the ex-gudards have not changed their political views much from the 1990s, when they were fans of Léon Degrelle. Chatillon and Péninque are close to Dieudonné and Alain Soral’s Égalité et Réconciliation (E&R), an ‘anti-Zionist’ movement which has a complicated relationship with the FN. Loustau is pictured doing the Nazi salute or drawing a swastika with grains of rice. None of the three are very presentable and they the contradict the public strategy of dédiabolisation, but they’ve made a hefty sum of money thanks to Marine’s FN and she has repeatedly defended all three when challenged.

In sum, dédiabolisation is about changing appearances without changing much of the reality. There have, to be sure, been changes – the most important one is a changing of the guard and the injection of new blood, which has brought about changes to the party platform and a new strategy more clearly aimed at winning power than remaining a perennial opposition. However, the supposedly ‘new and respectable’ rhetoric hides a party which, for the most part, hasn’t changed all that much and very much remains a ‘different’ party.

A series of electoral successes – and limitations

Regardless of what dédiabolisation is or is not, the public strategy of the ‘new’ FN has been a success. The appearances of a more respectable and credible party, with a newfound focus on socioeconomic issues or Islamism and a strongly anti-establishment rhetoric, have changed voters’ opinions on the party and made it more acceptable to a wider range of voters – while still being rejected by over half of the population.

Positive (blue) and negative (red) opinions of the FN since 2002 (source: Kantar)

Kantar (formerly TNS-Sofres) has an annual barometer on the FN, which shows what has changed and what hasn’t changed in the public’s opinion of the party. In 2017, 33% of respondents said that they agreed with the party’s ideas, a number which has remained remarkably stable since 2011 but which is higher than where it was for most of her father’s leadership (18% in 2010, but 28% in 2002). A similar percentage (36%) thinks that the FN does not represent a danger for democracy in France, a high percentage in historical perspective (33% in 2000, 29% in 2006) but lower than in 2013 (47%). A majority (54%, down from 62% in 2011) still perceives the FN only as an opposition party. Around 60-65% of voters say that they have never voted FN and do not plan on doing so, which nevertheless leaves a very substantial 40-35% of potential voters and a ‘hard’ floor of about 20%. Now as in the past, some of the FN’s ideas have wider appeal (toughness of justice, loss of citizenship for dual national Jihadists, defending traditional values, more powers to police) while others (withdrawal from the Eurozone) are widely rejected. Although LR (right-wing) sympathizers agree with the FN on issues like immigration, Islam, authority and tradition – the breaking point remains that a majority still see the FN as a dangerous and/or xenophobic party.

In the first electoral test of the Marine era, the FN won 15.1% in the 2011 cantonal elections and qualified for the runoff in 399 cantons (out of 1,440 candidates). It won, however, only 2 cantons. Marine Le Pen surged in polls for the 2012 election – polling about 18-20% for most of 2011 before falling off as the campaign began in earnest.

% vote for M. Le Pen by canton, 2012 (source: F. Salmon)

In the 2012 presidential election, Marine Le Pen won 17.9% of the vote, or 6.42 million voters, a record high for the party – higher than her father’s 2002 result (16.9%/17.8%). Le Pen expanded the traditional FN base both geographically (gaining in weak regions, more rural/exurban and less urban) and demographically (about 30% with workers and employees) and brought the far-right back to the heart of the French political system, after a short-lived ‘absence’ from 2007 to 2010. The election also confirmed the success and appeal of the anti-establishment ni droite ni gauche.

In the subsequent legislative elections in the summer of 2012, the FN’s results dropped off (like in 2002) to 13.6%, in part because the new dynamics of legislative elections since the ‘inversion of the electoral calendar’ (held right after presidential elections) mean that they ‘confirm’ the winner and depress turnout on the losing sides. For the 2012 legislative elections, the FN created the Rassemblement bleu Marine (RBM) as a FN-led ‘coalition’ to welcome independent candidates and assorted friendly minor parties (mostly souverainistes). The RBM served a dual purpose: to provide a banner for sympathizers still a bit queasy about the FN name (Gilbert Collard, an outspoken star lawyer), but also to hide some more offensive names (Renaud Camus, the ‘theoretician’ of the great replacement conspiracy theory). The FN qualified for the runoff in 61 constituencies and it won two seats, both in triangulaires, in the second round: Gilbert Collard in the Var and Marion Maréchal-Le Pen in the Vaucluse. Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, who was 22 at the time of her victory, became the youngest deputy in French history. The daughter of Yann Le Pen (her adoptive father is Samuel Maréchal), she is Marine’s niece and Jean-Marie’s granddaughter.

Marion Maréchal-Le Pen is presented by the media as Florian Philippot’s main rival in the party and a close ally of her grandfather. She adheres to a more traditional far-right line: more liberal on economic issues (less state interventionism, smaller government and against dependency), very socially conservative, focused on the old niche issues (immigration) rather than the new socioeconomic themes and close to the identitarian movement and the old and new political thought dear to the far-right (Charles Maurras, Maurice Barrès but also Renaud Camus’ great replacement or the ‘clash of civilizations’). It is Marion, as the ‘leader’ of the FN in the south, who brought the Nissa Rebela identitarians Philippe Vardon and Benoît Loeuillet to the FN in 2015. Very conservative on moral issues, she is a traditionalist Catholic who participated in the 2013 Manif pour tous and is favourable to laïcité only insofar as it can be a useful tool against “the propagation… of certain Muslims’ demands” – but opposes the traditional left-wing republican vision of it as ‘religious neutrality’ or ‘secular public sphere’. She does not care much about withdrawing from the Euro (or does not see it as a priority) and is clearly liberal on several economic issues, in contrast with Philippot or her aunt. Marion, who is ‘openly’ right-wing (rather than ni-ni), is favourable to a ‘union of the rights’ or an alliance of all the nationalist right. Marion Maréchal-Le Pen is very popular among the FN membership – she topped the list of candidates for the central committee at the 2014 congress, while Florian Philippot only finished fourth.

The media has presented her as the leader of the ‘southern Front’, as opposed to Philippot and Marine’s ‘northern Front’ – referring to the FN’s base in southern France – slightly more economically liberal, less working-class and ideologically right-wing than its (newer) northern bases. It is a somewhat simplistic view (at too macro a level) which caters to journalists’ need to dumb things down, but it nevertheless has some degree of truth to it. “Marion’s FN base” in the south, demographically, is a more poujadiste electorate of shopkeepers, small businessmen, artisans, retirees and lower professionals.

In the 2014 municipal elections, the FN ran 596 lists, including 422 lists in communes/arrondissements with over 9,000 inhabitants – the highest coverage of FN lists since 1995, although the FN remained absent from about half of all cities with over 10,000 inhabitants. The elections were the best municipal elections in the FN’s history – winning nine communes and one municipal sector (7th sector of Marseille) and supporting the victorious candidacy of Robert Ménard, the former boss of Reporters Without Borders, in Béziers. The FN, with Steeve Briois, defeated the Socialist incumbent by the first round in Hénin-Beaumont, ‘Marine-land’. Across France, the FN won about 1,500 seats in municipal councils. Despite the FN’s good results, anti-FN fronts républicains/strategic voting were successful in several high-profile runoffs – in Forbach (Philippot), Perpignan (Aliot) and Saint-Gilles (Collard).

In the June 2014 European Parliament elections, the FN became ‘the first party in France’ (well, behind 57% abstention) with 24.9% of the vote and 24 of France’s 74 seats. In percentage terms, it was the FN’s best result in any national election in its history. The FN confirmed that it was ‘the first party in France’ in the 2015 departmental elections, in which the far-right – with a remarkable coverage of 93% of cantons (1,897 candidates) – won 25.7% of the vote in the first round, a result quasi-identical to that of the European elections a year before. The FN’s success in the departmental elections showed just how much Marine Le Pen’s party had completely reconfigured the dynamics of France’s political system: the FN was present in the runoff in 60% of cantons (the previous high-water mark in a cantonal election for the FN was 2011, when the FN qualified in 27% of cantons, and before that in 1998, when it made it to the runoff in 21% of cases), while the percentage of ‘classic’ left-right runoffs fell to just 36% (57% in 2011, 66% in 2004). Sign of the left’s collapse, it was eliminated from nearly 30% of runoffs.

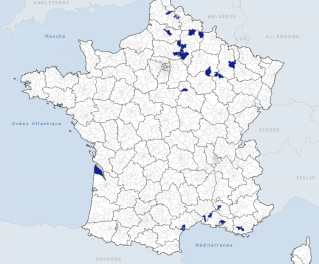

Cantons won by the FN in the 2015 departmental elections (source: Geoclip)

In the second round, the FN was qualified for the runoff in 1,105 cantons but won in just 31 – winning 62 seats (with the new electoral system). The FN had hoped to capture the departmental presidencies in some of its strongholds (Aisne, Vaucluse), but it both cases it fell flat: in the Aisne the FN won 8 seats against 18 for the right and 16 for the left; in the Vaucluse, the far-right (the FN and Orange mayor Jacques Bompard’s Ligue du Sud) won 10 seats (6 FN, 4 LDS) against 12 each for the left and right (the right won the departmental presidency as the tie was broken in favour of the oldest candidate).

The 2015 regional elections would show the FN’s major difficulties at breaking its ‘glass ceiling’ in the second round to win. The first round of the December 2015 regional elections was a major success for the FN, which won 27.7% nationally and a new historic record in terms of raw votes (6 million). It peaked at 40% in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie (with Marine Le Pen) and PACA (with Marion Maréchal-Le Pen), and won 36% in Alsace-Lorraine-Champagne-Ardenne (with Florian Philippot). It placed first in 6 regions, and was in a strong position to carry at least one if not two or three. However, the PS, pushed by Hollande and Valls withdrew in both NPDCP and PACA (where it was third) in favour of the LR candidates (Xavier Bertrand and Christian Estrosi respectively) to form a front républicain to block the FN (which would have carried both in a triangulaire). The PS candidate in ACAL, Jean-Pierre Masseret, disobeyed national orders and refused to withdraw, but he was stripped of his PS endorsement. The second round, like in 2002, thus became defined as being about the FN, or ‘blocking’ the FN.

In the second round, although the FN won a new record in terms of votes (6.8 million), it was defeated in every region. The de-facto fronts républicains in NPDCP and PACA worked almost to perfection, despite those two regions being the FN’s strongholds: Marine Le Pen lost 57.8% to 42.3%; Marion Maréchal-Le Pen lost 54.8% to 45.2%. In ACAL, even if Masseret did not withdraw, there was widespread anti-FN strategic voting for LR candidate (Philippe Richert) and Philippot lost 36.1% to 48.4%, gaining less than 150,000 votes between the two rounds while the right gained 600,000. Nationally, a significant increase in turnout – from 49.9% to 58.4% – between the two rounds hurt the FN, as new voters broke heavily against them in all regions. Increased turnout is calculated to have cost the FN about 1.5% on average.

The FN’s difficulty at breaking the ‘glass ceiling’ in second rounds in 2015 was analyzed at length in this Fondapol publication. In the 2015 departmental elections, the FN won 4 cantons in the first round and 27 in the runoff. Of those 27, 20 were won in two-way runoffs against the left, where the FN gained on average 9.5% between both rounds. It won 4 in triangulaires (three-ways) and 3 in runoffs against the right. It lost in 538 runoffs against the right, 250 triangulaires (including 29 of the 33 triangulaires in which it had finished first in the first round) and 274 runoffs against the left. In runoffs against the right, the FN gained on average 5.3% between both rounds, significantly less than what they gained in runoffs against the left. A chunk of first round mainstream right voters voted for the FN against the left in left-FN runoffs, but less so than in the past (because the FN started off from a much higher first round level in 2015 and had less to gain); very few (no more than 10%) of first round left-wing voters voted for the FN in right-FN runoffs, where the FN’s gains between both rounds were also smaller in 2015 than in past cantonal elections. In triangulaires, the FN on average lost 2.2% between both rounds; this was again the case in the 2015 regional elections (with some exceptions). The FN has always tended to lose votes in three-way runoffs, because some of their first round voters either just wanted to express dissatisfaction or lodge a protest vote in the first round while others vote strategically. For example, in the 2015 regional elections in Île-de-France, the FN – which was third in the first round and therefore had no chance at winning – lost 4.4% between both rounds (from 18.4% to 14%) because about a quarter of first round FN voters voted strategically to defeat the PS in the runoff.

Fondapol calculated, on the basis of the 2015 departmental elections, that in two-way runoffs the FN needed to have won at least 40% in the first round to have a chance at winning against the left, or 45% to have a chance against the right.

Between 2012 and 2017, the FN reconfigured the dynamics of French politics – what had traditionally been a two-bloc system with the far-right as a strong third force became a more unpredictable three-bloc system around the left, right and far-right. The FN further expanded its potential electorate, with particularly strong support among workers, employees, shopkeepers/tradesmen and less educated voters. The FN’s successes made it clear that it would not only be a major force to be reckoned with in 2017, but that Marine Le Pen was very likely to qualify for the second round – like her father had in 2002, except with a result in the vicinity of 25% rather than just 17%. Nevertheless, the ‘second-order elections’ in 2014-5 made clear that the FN still struggled to overcome the final, but most important, obstacle: actually winning (in the runoff).

Controversies and scandals