Monthly Archives: March 2014

France 2014 (R1)

The first round of municipal elections were held in France on March 23, 2014. The municipal councils of nearly all 36,681 communes in France – in metropolitan France, Corsica and all but four overseas collectivities. I covered the complex structure, workings, powers and responsibilities of French municipal government as well as the details on the electoral systems in a first preview post. In a second preview post, I listed the major races in the main towns.

To summarize, for those unwilling to read the full details, in communes with over 1,000 inhabitants (which means about 9,000 communes altogether, but making up the vast majority of the population), elections are held by closed party-list voting. In the first round, a list must obtain over 50% of the vote to win outright. If no list wins outright, all lists which won over 10% of the vote are qualified for the second round while lists which have won over 5% of the vote may ‘merge’ (fusion) with a qualified list, which means that the list with which they merge will be altered to include names of candidates who were originally on the list which was merged. Lists who have won over 10% of the vote may also choose to withdraw without merging, or withdraw and merge with another qualified list. In the second round, a relative majority suffices. The list which wins, either in the first or second round, is immediately allocated half the seats in the municipal council. The other half of seats are distributed proportionally to all lists, including the winning list, which have won over 5% of the vote. In Paris, Lyon and Marseille the electoral system is different. Although the above rules are in place, the election is not fought city-wide: instead, it is fought individually in arrondissements/sectors (20 in Paris, 9 in Lyon and 8 in Marseille).

The size of the municipal council varies based on the population of the commune, from 7 to 69 seats. Lyon has 73 seats, Marseille has 101 and Paris has 163.

As explained in detail in the first preview post, the election – the first since the 2012 presidential and legislative elections – comes as President François Hollande is extremely unpopular – with about 20% approval ratings, he is one of the most unpopular president of the Fifth Republic. It owes to the terrible economic situation (over 10% unemployment), the government’s perceived inability to deal with these economic problems, its general ineptness and internal dissonance and policies which have won the opposition of both the right and much of the left. Going into the municipal elections, the left hoped that the local dynamics which are often predominant in municipal elections would prevail; but it certainly feared the precedent of the 1977 and 1983 ‘wave’ municipal elections which saw huge one-sided waves against the governing coalition.

A note on terminology used in this post, in French, because hard to adequately translate in English: an adjoint au maire is a deputy mayor, responsible for a given portfolio, but the use of deputy mayor would cause confusion to Francophones since député-maire in France is commonly used to refer to one who serves concurrently both as deputy in the National Assembly (député, MP) and mayor. A premier adjoint is the ‘first deputy’ or top-ranking adjoint to the mayor. A triangulaire is a three-way runoff, a quadrangulaire is a four-way runoff.

Overview

Abstention was about 36.45% according to the Interior Ministry, down from a 39.5% prediction fro an Ipsos estimate at around 8pm on election night. This is a record low turnout for a municipal election since the War, down from the previous low, set in 2008 (33.5% abstention), and following a consistent trend of declining turnout since 1983 (21.6% abstention). There was much talk in the media from journalists and politicians about the ‘record low’ turnout and some grandiose declarations from politicians trying to put their spin on things, but it helps to put things in perspective. While following a trend of declining turnout in local elections, turnout was higher than in the 2012 legislative elections (57.2% in the first round) and far better than the last two subnational elections (2010 regionals: 46.3% turnout in the first round; 2011 cantonals: 44.3% turnout in the first round). It is obvious that part of the explanation stems from greater dissatisfaction with politics and the political system in general, a widespread feeling that no party adequately represents their feelings and/or a view that politicians are all ‘the same’ and not worth our time. However, researchers have argued that the trend has been been the result of a decline in ‘regular voting’ and the rise of ‘sporadic participation’ (participation intermittente) – voters turn out based on the stakes of the specific election, rather than turning out ‘by duty’ in every type of election as in the past (when turnout at all types of elections was generally similar across the board). This is evidenced by the very high turnout in the last two, high-stakes, presidential elections in 2007 and 2012 (83.8%, 79.5%); this disproves the idea that there is a general civic crisis. The rise of sporadic participation is a result, partly, of generational changes: older voters (except those over 75-80) feel a ‘duty’ to vote in all elections, while younger voters are more likely to be sporadic voters (and the 20% or so who never vote are also over-represented in younger age groups).

As in the past, turnout was highest in rural communes with a small population (where voters often personally know the candidates and the municipal election has a very local, close-to-home dimension) while it was lowest in the largest urban areas (56.3% in Paris, 53.5% in Marseille, 56.1% in Lyon). Abstention was particularly high, again, in low-income and historically working-class towns hit hard by unemployment and social crises: 62% in Vaulx-en-Velin, Roubaix, 61% in Évry, Stains, 59% in Bobigny, 58% in Saint-Denis and Aubervilliers. Sporadic voting and systematic abstention is positively correlated to lower levels of education and incomes; the feeling of political dissatisfaction and disconnect with the political system is particularly acute in those places. This excellent number-crunching post from Libération also lists the major towns (pop. over 10,000) with the lowest abstention: Corsica (21% in Bastia) and La Réunion feature prominently on the list, along with some smaller towns in metro France (generally in the western half). Corsica is an interesting case, because it has particularly low turnout in presidential elections (74.3% in 2012) but very strong turnout in more localized elections because there’s a much closer connection to local politics (which are very clan/family-based) on the island. La Réunion appears to be a similar case.

Ipsos’ ‘exit poll’ of sorts confirmed the positive correlation between age and higher turnout and job status and higher turnout (49% of manual workers voted, 65% of managers and higher professionals did so). In past elections where the governing party is particularly unpopular (2010 regionals, for example), turnout from government supporters was lower. Something similar seems to have happened, but it seems as if the issue was mostly that right-wing voters were far more mobilized than left-wing voters staying at home: 68% of PS sympathizers voted, compared to 75% of UMP/UDI sympathizers. Greens (56%) and FN (60%) sympathizers and those without partisan sympathies (50%) had lower turnout. When asking non-voters why they didn’t vote, 44% said that the elections would have no impact on their daily lives, 39% said to show opposition towards politicians in general and 22% said to show opposition to the government. 34% of voters said that they would use their vote to show opposition to the government and Hollande, but 55% said they would neither oppose or support the government through their vote. And only 23% said that their vote would be determined by the national political situation (rather than local).

The overall result of the first round can be summarized thus: a major victory for the far-right FN, a bad thumping for the governing PS and the makings of a good overall election for the UMP. What retained attention in the French and foreign press was the FN’s success; in those cities where the FN stood, the FN won 16.5% of the vote, up from 9.2% in 2008. In places where the FN has a strong local footing in place, the results were rather tremendous, improving significantly on Marine Le Pen’s local performance there in 2012 and on the FN’s results in the 2012 legislative elections. In Hénin-Beaumont (Pas-de-Calais), a poor town in the old coal mining basin of northern France which Marine Le Pen has turned into her solid electoral base since 2007, the FN’s candidate, Steeve Briois (Le Pen’s local lieutenant and ally) was elected mayor by the first round with 50.3% of the vote, defeating a sitting PS mayor. The FN placed first in four major cities in southern France: Perpignan (Pyrénées-Orientales), Béziers (Hérault), Avignon (Vaucluse) and Fréjus (Var). It also placed first in smaller towns such as Saint-Gilles (Gard), Beaucaire (Gard), Tarascon (Bouches-du-Rhône), Brignoles (Var), Digne-les-Bains (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence) and Forbach (Moselle). It obtained very strong results in many other cities, most significantly Marseille, where the FN placed second overall, ahead of the PS. It also did well (over 25%) in Carpentras (Vaucluse), Sorgues (Vaucluse), Cavaillon (Vaucluse), La Seyne-sur-Mer (Var), Noyon (Oise), Hayange (Moselle), Elbeuf (Seine-Maritime), Le Petit-Quevilly (Seine-Maritime) and several towns in the Pas-de-Calais mining basin.

As Libé’s analysis of the results in the communes with over 10,000 inhabitants pointed out, in the 409 of those communes with FN lists, the FN won 14.4%, which is down from Le Pen’s 15.7% in 2012. However, in the FN’s top 10 communes on March 23, where they took 39.9% on average, Le Pen had taken ‘only’ 29% in 2012, so there was a clear improvement on the FN’s presidential result in towns where the FN lists were headed by well-known national (or local) figures. So there remains an heavy element of local notoriety and implantation, even in the FN’s result. All that notwithstanding, it was very much a great night for the FN. Municipal elections, as Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, are traditionally a rather difficult election for the FN (reasons explained more thoroughly in the intro to my second preview post): difficulty to run lists in many places, lack of local infrastructure (no incumbents in most cases, lack of office holders, weak local party) and the focus on local issues and local dynamics; although the FN did comparably well in 1995. Therefore, that the FN has been able to draw a significant number of voters to vote for their lists (in many cases, led by nobodies or obscure party bosses and officeholders) in a locally-focused election is a clear success for the FN. It is also good news for them that they came close to matching Le Pen’s 2012 result (and in many cases exceeded it too); Marine Le Pen’s result in April 2012 was a high point for the FN and she likely drew protest voters to her name who would usually not vote for the FN in other types of elections.

The results also showed that the FN’s influence has ‘nationalized’ further, with the party winning impressive results in towns where the FN has usually been weak: most notably in Brittany – with over 10% in Saint-Brieuc, Lorient and Fougères but also 15% in Le Mans and 17% in Limoges.

Overall, Libé calculated that in all communes with a population of over 10,000; the result was 46% for the right (+3.5 since 2008), 42.3% for the left (-7.9), 8.9% for the far-right (+7.4) and 2.7% for others (-3.1). On the left, the main loser were the governing leftist parties (from 44.6% in 2008 to 36.4% in 2014) and specifically the PS (from 36.3% to 25.7%) while EELV and other centre-left parties/candidates (DVG) gained ground. As some cities show (most notably Grenoble) there was a strong vote for left-wing candidates outside the PS; in other places, it is also clear that the PS label hurt candidates, with Montreuil being the best example.

The national mood hurt the PS far more than pollsters had expected it, with Marseille as the most catastrophic example of a place where the PS had high hopes going into March 23 and are now wondering what the f- just happened. In several cities, especially Marseille, the pollsters were wrong – often underestimating the FN, but also overestimating the PS in a lot of cases. What happened? The FN’s underestimation is nothing new and can be expected; some people apparently don’t want to admit a FN vote to pollsters (or there was a strong last minute swing to the FN in the booth). The PS’ overestimation is more surprising (if anything, in some cases, an unpopular governing party can be slightly underestimated) and pollsters should have some answering to do (especially in Marseille). Was it their turnout models? The turnout was not a surprise to anyone who had been following things, and pollsters knew that and their turnout estimates were generally correct. Was it the difficulty of polling a fairly micro level?

As it stands, the PS will lose several mid-sized towns to the UMP/UDI in the second round: Amiens, Valence, Pau, Laval, Chambéry, Roanne, Charleville-Mézières, Salon-de-Provence, Saint-Chamond, Aulnay-sous-Bois, Montbéliard and Brive-la-Gaillarde are lost and can’t be salvaged; the PS is clearly in trouble in Caen, Angers, Evreux, Angoulême, Saint-Étienne, Ajaccio, Belfort and Quimper and the runoff will be close in Strasbourg, Reims, Tours, Tourcoing, Clichy, Pessac and other towns. With the threat that vote transfers from EELV or Left Front (FG) candidates eliminated or withdrawn will be bad, the second round could be a real rout for the PS with very few chances at compensatory gains (Avignon, Bourges, Calais, Douai and Corbeil-Essonnes are the only major ones in which the PS retains a fighting chance at gaining the seat from the UMP/UDI). It could end up like 1983, although the second round in 1983 there had been a small rally-round-the-flag effect on the left which allowed the PS to unexpectedly save a few things (Lille).

Several major towns (population over 30,000) and many smaller towns (population over 10,000) have already switched from left to right. By the first round, the largest city to switch sides is Niort (pop 57,813, Deux-Sèvres), where incumbent PS mayor Geneviève Gaillard, elected in 2008, was defeated by Jérôme Baloge (UDI) in a landslide – 54.3% against only 20.4%. Niort, whose economy is famously based around insurance mutuals and the ‘social economy’, is a left-wing stronghold, having voted 64% for Hollande in 2012 and being governed by Socialist mayors since 1957. Gaillard, who has been deputy for the area since 1997, gained the city hall in 2008, running as the official PS candidate against the incumbent mayor, Alain Baudin, who was not selected by the PS and ran as a dissident. The episode created much bad blood on the left, and Gaillard was accused by members of the PS majority of authoritarianism. Her 2008 opponent, Alain Baudin, was third on Baloge’s list. Gaillard charges that Ségolène Royal, the PS regional council president, may have had a role to play in her defeat, after a communiqué from Royal said that Niort hadn’t switched to the right but rather been won by a list of a ‘large coalition’ against a ‘list of divisions and cumul des mandat‘.

Also lost by the first round is Clamart (pop 52,731, Hauts-de-Seine), where incumbent PS mayor Philippe Kaltenbach was forced to retire after being indicted in a corruption case in 2013. The UMP-UDI list led by local opposition leader Jean-Didier Berger, an ally of Philippe Pemezec, the UMP mayor of Le Plessis-Robinson (and longtime rival of Kaltenbach), won 53.8% against 32.9% for the PS-EELV-PCF list. In the Yvelines department, Poissy (pop 37,662), a right-leaning town gained by the PS in 2008, switched back to the right with no less than 62.4% for the UMP against 24.8% for the PS incumbent. The PS’ victory in 2008 owed much to Jacques Masdeu-Arus, the UMP mayor in office since 1983 who at the time had been sentenced in a corruption case but since he was appealing he was able to run for reelection. In the Val-de-Marne, the UMP defeated the PS incumbent in L’Haÿ-les-Roses (pop. 30,574) by the first round, 54.1% against 46%. The town had been ruled by Socialists since 1965 and Hollande won 59.8% in this middle-class suburban community in May 2012. The incumbent who was defeated had taken office in 2012, after his predecessor was indicted in a corruption case in 2011.

Another gain for the right was Chalon-sur-Saône (pop. 44,847, Saône-et-Loire), historically a small industrial centre gained by PS in 2008 after 25 years of right-wing rule, where incumbent PS député maire Christophe Sirugue was defeated 32.6% to 52.4%. Other gains in smaller towns include Châteauneuf-les-Martigues (a defeat for incumbent PS député maire Vincent Burroni), the Toulouse suburb of Balma, Dole (a victory for UMP deputy Jean-Marie Sermier), Ablon-sur-Seine, L’Aigle, Sainte-Luce-sur-Loire and the emblematic troubled post-industrial town of Florange.

Comparable gains for the left are far fewer: only one town with over 10,000 people seem to have switched – Vire (Calvados), where the UMP incumbent since 1989 was retiring and a PRG general councillor replaces him.

The government’s clear defeat in the first round and a second round which will probably largely confirm the first has taken the government by surprise and there is increasing talk of an early cabinet shuffle, originally expected for the aftermath of the European elections in May (where the PS knows it will perform horribly). Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault, who is as unpopular as Hollande and very much of a low-key non-entity with weak authority over his cabinet, may be replaced and other cabinet ministers will likely go too. Cabinet shuffles are commonplace in France after a government takes a thumping in a midterm election, and it rarely improves matters for the government in the long run.

Detailed results analysis: 12 largest cities

Paris

| Arr. | UMP-UDI-MD | PS-PCF-PRG^ | EELV | FN | PG | Paris libéré | DVD | DVG | LO | NPA | OTH |

| 1 | 51.72 | 27.36 | 10.84 | 5.03 | 2.53 | 0.49 | 2.02 | ||||

| 2 | 24.25 | 22.82 | 32.96 | 3.97 | 2.8 | 1.88 | 11.01 | 0.31 | |||

| 3 | 29.09 | 47.29 | 10.78 | 4.99 | 3.99 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.95 | |||

| 4 | 37.82 | 37.4 | 9.3 | 5.2 | 3.82 | 5.86 | 0.61 | ||||

| 5 | 28.49 | 33.94 | 8.92 | 3.62 | 4.39 | 19.43 | 0.64 | 0.57 | |||

| 6 | 52.62 | 26.12 | 6.65 | 4.8 | 2.36 | 3.36 | 3.64 | 0.45 | |||

| 7 | 41.01 | 16.92 | 3.04 | 5.95 | 1.1 | 2.98 | 17.81 7.52 3.63 |

||||

| 8 | 46.61 | 15.4 | 3.5 | 4.76 | 1.41 | 19.26 | 5.16 | 3.86 | |||

| 9 | 39.42 | 39.15 | 8.01 | 4.86 | 3.72 | 4.24 | 0.57 | ||||

| 10 | 21.48 | 44.36 | 11.49 | 5.41 | 6.41 | 4.85 | 3.35 | 0.61 | 0.95 | ||

| 11 | 26.82 | 44.75 | 11.55 | 5.47 | 6.27 | 3.14 | 0.63 | 1.32 | |||

| 12 | 33.34 | 37.39 | 10.06 | 6.76 | 5.38 | 0.55 | 0.86 | 5.62 | |||

| 13 | 24.98 | 44.46 | 9.82 | 7.46 | 5.87 | 1.74 | 1.06 | 0.78 | 1.33 | 2.5 | |

| 14 | 33.1 | 37.89 | 8.77 | 5.74 | 5.24 | 5.74 | 0.66 | 2.83 | |||

| 15 | 48.56 | 29.1 | 4.46 | 6.3 | 2.68 | 4.64 | 2.72 1.5 |

||||

| 16 | 63.04 | 12.98 | 2.31 | 6 | 1.04 | 9.31 | 5.3 | ||||

| 17 | 53.53 | 25.38 | 6.58 | 6.45 | 3.08 | 4.43 | 0.52 | ||||

| 18 | 25.23 | 39.85 | 12.65 | 6.78 | 7.18 | 3.62 | 1.15 | 1.85 1.65 |

|||

| 19 | 25.76 | 42.18 | 12.86 | 7.94 | 7.11 | 1.36 | 1.04 | 1.72 | |||

| 20 | 17.5 | 37.29 | 10.89 | 7.48 | 10.35 | 2.21 | 3.35 | 7.91 0.82 |

0.79 | 1.36 | |

| Paris | 35.91 | 34.40 | 8.86 | 6.26 | 4.94 | 3.36 | 2.84 | 1.01 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 1.31 |

In Paris, the UMP-UDI-MoDem lists led by Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet (NKM) came out with a narrow lead in the city-wide popular vote, raising optimism and confidence on the right while warning Anne Hidalgo, the Socialist candidate and favourite to succeed retiring PS mayor Bertrand Delanoë, that the contest might not be the walk in the park many on the left thought it would be. Of course, a city-wide lead in popular vote is meaningless: the election in Paris, as noted in the intro, is not decided based on the share of the votes across the city but rather by the victor in each of Paris’ 20 arrondissements. It is very much like the electoral college in the United States, and like in the US winning the city-wide popular vote doesn’t necessarily mean you won the election.

In this case, the actual race in the arrondissements indicates that Hidalgo, the PS candidate, remains the narrow favourite to win in the second round. The UMP pulled ahead of the PS in two arrondissements currently held by the PS – the 4th and 9th arrondissements, where the UMP has a tiny lead (less than 1 point) over the PS and trails the combined total of the left. Even if the UMP were to win both these arrondissements on March 30, it would not be enough because they have 2 and 4 conseillers de Paris respectively. As a handy simulator on Slate.fr shows, if the 4th and 9th go right and nothing else moves, the left would win with a comfortable majority on council (about 89 seats, with 82 required for a majority).

Instead, the key ‘swing states’ in Paris are the 12th and 14th arrondissements: two historically right-leaning sectors which were held by the right until the PS’ victory in 2001 and have swung to the left in national elections, with Hollande winning 58.9% and 60.3% in those two arrondissements in 2012. NKM is the UMP’s top candidate in the 14th arrondissement, while the young sitting municipal councillor Valérie Montandon is the UMP’s top candidate in the 12th. The 12th is, like Paris, predominantly middle-class with a mix of young, highly-educated professionals (leaning left) and an older, more established bourgeoisie on the right; although there’s also a significant number of residents in low-rent housing (HLM). The 14th is rather similar, although with a slightly larger share of the population lives in HLM.

On March 23, the PS lists placed ahead of the UMP lists in both these key arrondissements, with 37.4% to 33.3% in the 12th and 37.9% to 33.1% in the 14th. With the merger of the EELV lists (10.1% and 8.8% respectively) into the PS lists, the left solidifies its lead – and has smaller and probably less certain reserves with those who voted for the PG lists (5.4% and 5.2% respectively) in the first round, even if there is no merger agreement between the PS and PG in Paris.

Yet, if NKM is to become mayor, the UMP lists must absolutely win both arrondissements, and that would give them a very narrow 82-81 majority in the Council of Paris. Victories in the 4th and/or 9th arrondissements are not absolutely necessary, but they would share up a more comfortable majority.

This also assumes that the UMP holds all arrondissements it currently has, whereas the 5th arrondissement is very tight. In the first round, the PS list won 33.9% against 28.5% for the UMP list, with a dissident list led by Dominique Tiberi, the son of the incumbent mayor (and former RPR mayor of Paris from 1995 and 2001, indicted for corruption and sentenced for voter fraud in 2013) Jean Tiberi, won 19.4%. NKM dodged a fatal bullet by reaching a merger agreement with Tiberi’s list, likely in exchange for juicy concessions to Tiberi (who had a very strong bargaining position). The 5th is an old right-wing stronghold – it was where Jacques Chirac got elected when he was mayor from 1977 to 1995 – but it has shifted to the left in the past few years, with Hollande winning 56.2% of the vote there in May 2012. The runoff there will be close, but assuming good transfers from Tiberi to the UMP, the right has a narrow advantage. But defeat in the 5th would be fatal to the UMP’s chances of winning Paris.

Therefore, given the numbers and where the race is fought, Hidalgo and the left remain the favourites. Nevertheless, the first round results and the UMP’s strong performance means that they cannot be overconfident. The UMP had a much better performance than in 2008, when it won only 27.9% of the vote; meanwhile, the PS lists took a sharp hit from Delanoë’s landslide result in 2008, when the PS lists had won 41.6% in the first round. The national climate played a major role, but the contest was also ‘fairer’ than in 2008: Hidalgo is less charismatic and not as strong a candidate and Delanoë (and she also lacks the advantages of incumbency), while NKM is clearly a much stronger UMP candidate than Françoise de Panafieu, a boring old politician. NKM was mocked for her somewhat aloof and bourgeois/snob airs (most notably her gaffe on the Paris subway being extraordinary and filled with charming characters), and her campaign was wracked by the highly-publicized string of dissident candidacies on the right (as well as squabbles between the UMP, UDI and MoDem for the lists); but her moderate platform (focused on the ‘middle-classes’ and a promise not to raise taxes) was a fairly good fit for a right-wing candidate in contemporary Paris.

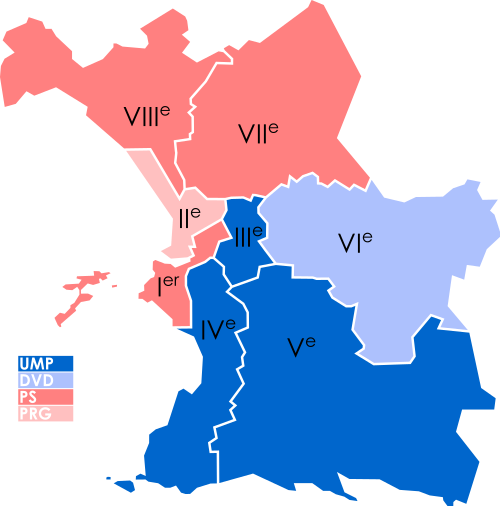

The UMP won four arrondissements by the first round. In the 1st, a small high-end bourgeois district in central Paris, incumbent mayor Jean-François Legaret (UMP) was reelected with 51.7% while the PS list lost 10 points from its 2008 result. In the 6th, another bourgeois district, UMP incumbent Jean-Pierre Lecoq won 52.6%. In the 16th, the wealthiest and most right-wing arrondissement in Paris, incumbent mayor and deputy Claude Goasguen was reelected handily with 63% against 13% for the PS and 9.3% for David Alphand, a sitting DVD arrondissement councillor backed by Charles Beigbeder’s Paris libéré lists. in the 17th, incumbent UMP mayor Brigitte Kuster won 53.5% against 25.3% for Annick Lepetit, a PS deputy (the PS’ result is down 11 points from 2008 here). Although the southwestern half of the arrondissement is very bourgeois and right-wing, the Épinettes (and parts of the Batignolles) in the northeast are quite strongly left-wing (the Épinettes is a former working-class neighborhood which is largely gentrified by young professionals, although it remains significantly poorer than the rest of the arrondissement; there are also significantly poorer peripheral areas with HLM towers lining the périph).

In the 7th and 8th, two other solidly right-wing very affluent arrondissements, the UMP will have to wait for March 30 to win, because of strong dissident candidates on the right. In the 7th, UMP mayor Rachida Dati, who has her share of enemies on the right (she is criticized locally for not caring much about her gig as mayor of the 7th), did poorly with 41% of the vote. Christian Le Roux, a former maire adjoint of the arrondissement, placed second with 17.8% while Michel Dumont, who was mayor of the arrondissement until being pushed aside for Dati in 2008, won 7.5%. In the 8th, the UMP list won 46.6%, while Charles Beigbeder, the ringleader of the Paris libéré alliance of right-wing dissidents, won 19.3%. Overall, the performances of Beigbeder’s otherwise little-known candidates was mediocre; except in the 16th where the candidate was a sitting councillor and in the 14th (NKM’s arrondissement) where his candidate was Marie-Claire Carrère-Gée, the traditional local UMP candidate in the past who was sidelined to make way for NKM.

In the 2nd arrondissement, dissident candidate Hélène Delsol won 11% of the vote (and fourth place); she was the original UMP candidate until NKM removed her in early March because her list did not respect the UMP’s deal with the UDI (Delsol was also a close supporter of the anti-gay marriage Manif pour tous; NKM was one of the few UMP deputies not to vote against the bill when it passed – she abstained). It was also in the 2nd arrondissement, on the left since 2001 and likely to remain so on March 30, that EELV did best: Jacques Boutault, who has been the Green mayor of the arrondissement (thanks to an agreement with the PS) since 2001, topped the poll with 33%, up from 29.9% in 2008 (when he had placed second behind the PS list in the first round).

Unlike in 2008, when the PS won several of its strongholds by the first round, no PS list won outright on March 23. Its best performance came from the cosmopolitan and ‘bobo’ 3rd, where incumbent mayor Pierre Aidenbaum won 47.3%.

Again, the results reflected the old east-west polarization in Paris; the UMP’s best performances came from the beaux quartiers – old conservative strongholds which have been on the right for over 100 years while the PS did best in the east – which used to be heavily working-class and revolutionary neighborhoods known for their revolutionary ferment (the east was where the barricades went up in 1848 and where the 1871 commune took longest to crush) and socialist history. However, Paris is now a middle-class city which were few workers; the contrast is now between an older, established and very affluent bourgeoisie and ‘new middle-classes’ – younger, mobile, highly educated, less affluent (but not poor) professionals with high cultural capital (often working as cadres, many as journalists, academics, artists etc) living in the gentrified neighborhoods of eastern Paris. There are, however, deep social inequalities, and the high housing prices (a major issue in this election) have pushed out the lower middle-classes and working poor. Paris still has a significant poor population (many immigrants or foreigners), with heavy concentrations in a string of HLM towers in the periphery of the city.

The PS’ other best results came from the eastern arrondissements of the 10th, 11th, 13th (all over 44%), the 18th (nearly 40%) and the 19th (42%). The 10th is known as a ‘boboland’ (the Canal Saint-Martin is known as a ‘bobo’ hotspot) although it includes some poorer immigrant-heavy areas (Porte Saint-Denis, Bas Belleville). The 13th remains one of Paris’ poorest areas, with a lot of social housing but also some gentrified middle-class areas. The 18th includes Montmartre, a famously hip bobo area, but also La Goutte d’Or, a working poor neighborhood with a very large immigrant population. The 19th, historically working-class, is similar: there is a contrast between deprived peripheral areas (La Villette) and some more recently gentrified areas (Buttes-Chaumont). The 20th is the most left-wing arrondissement in Paris, with 71.8% for Hollande. The PS did not do as well (37.3%) because of competition from EELV but also the PG (Danielle Simonnet, the PG’s mayoral candidate ran here) which won its best Parisian result (10.4%) and from former PS mayor Michel Charzat (7.9%, he was mayor until 2008, when he ran as a dissident and won 30.5% in an all-leftist runoff against the PS-Green list). The 20th includes most of Belleville, an old working-class neighborhood which has a huge symbolic place in French socialist mythology (being identified in collective memory as the socialist, revolutionary working-class stronghold); the 20th and 19th remain two of the city’s poorest areas, and there are still many pockets of deprivation in Belleville and the periphery, but there has been recent gentrification here as well.

In the 15th, a bourgeois (but not always so: until the 1950s, it was more blue-collar and the PCF polled quite well) arrondissement where Hidalgo has run in the past, her own list did poorly with only 29.1% against 48.6% for the UMP list led by incumbent mayor Philippe Goujon.

EELV won 8.9%, a good result for the party, improving on the Greens’ 6.8% in 2008 but still below their 2001 results. It quickly found an agreement with the PS, and EELV’s lists will merge with those of the PS in every arrondissement.

EELV’s support is also very eastern, with low support in the conservative west (‘green-minded’ voters there find the Greens far too left-wing). This year, EELV, outside the 2nd, did well in the downtown core (1, 3), the inner east (10, 11, 12) and outer east (18, 19, 20) – over 12% in the 18th and 19th. In the 18th, EELV polled over 15% in Montmartre and Clignancourt, but it also did quite well (over 10%) in La Goutte d’Or; in the 19th, it did best the Buttes-Chaumont area, with peaks over 20%. There has been gentrification in all these areas and there is a large potential EELV-type electorate, but these very good results may also indicate that EELV was a ‘replacement vote’ on the left for those who didn’t want to vote PS in the first round.

The PG, on the other hand, did poorly – its 4.9% result is a disappointment for them, although the silver lining is that Simonnet qualified for the second round in the 20th, with a bit over 10% of the vote. The PG and PS found no agreement and Simonnet maintains her list in the runoff; the PS seemed to have very little interest in reaching an agreement with the PG, with the PG decrying the conditions in which they were received by the PS (in some backroom which looked more like a storage shack). The lack of agreement between the PG and PS further deepens the rift between Mélenchon’s PG and the PCF, which supported the PS by the first round. In the second round, the PG will therefore be on opposite sides from the PCF. In the 20th, PG supporters will be hoping that Simonnet’s list wins at least 12.5% to obtain one seat for the PG on the municipal council.

The FN won 6.3%, doubling its 2008 result (a terrible 3.2%) but effectively just matching Le Pen’s 2012 result in Paris (6.2%). Although Paris was once a FN stronghold – in 1984, for example – the city, with the aforementioned social and cultural changes, has become a dead zone for the far-right whose results have gotten progressively worse since the late 1980s. There was no clear east-west divide in the FN’s vote in 2014, like in 2012; instead, the FN polled best in poorer peripheral areas on the outskirts of the city.

The second round may prove closer than expected, but the dynamics and structure of the election indicate that Hidalgo, despite a mediocre first round showing, remains the favourite, especially in the two key arrondissements where the election will be played out.

Marseille

| Sector | UMP-UDI-MD* | FN | PS-EELV | FG | Diouf | PRG | DVD | DVG | EXG | OTH |

| 1 | 38.6 | 15.02 | 26.96 | 8.98 | 6.96 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 2.53 | ||

| 2 | 24.18 | 16.54 | 17.46 | 7.11 | 5.41 | 23.81 | 1.1 | 4.38 | ||

| 3 | 41.76 | 18.15 | 24.66 | 7.71 | 5.15 | 0.91 | 0.31 | 1.35 | ||

| 4 | 50.08 | 17.31 | 19.08 | 7.02 | 6.52 | |||||

| 5 | 45.78 | 25.56 | 15.28 | 6.07 | 4.39 | 1.73 | 1.19 | |||

| 6 | 35.17 | 25.85 | 16.63 | 5.53 | 3.43 | 13.4 | ||||

| 7 | 27.83 | 32.88 | 21.66 | 6.43 | 8.1 | 2.17 | 0.92 | |||

| 8 | 21 | 27.59 | 31.71 | 10.8 | 5.47 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 1.7 |

After the first round, Marseille came to symbolize the rout of the PS. The city, which was the stronghold of Socialist strongman Gaston Defferre between 1953 and 1986, has been governed by the UMP’s Jean-Claude Gaudin since 1995 and the PS has been eager to regain Marseille ever since it lost it. It came very close in 2008, and despite the unfavourable national climate, it had some reason to be optimistic this year. The polls all confirmed a very tight race between Gaudin and PS-EELV candidate Patrick Mennucci; in the 3rd sector, the key ‘swing’ sector in Marseille, all polls showed a nail-bitingly close contest between UMP mayor Bruno Gilles and the PS’ star candidate, junior minister Marie-Arlette Carlotti. When the results came in, the PS was left reeling – in awe, wondering what just happened. The pollsters were all wrong: the UMP lists placed far ahead of the pack, with 37.6%, against 23.2% for the FN and 20.8% for the PS-EELV. All the hopes of gaining Marseille were crushed in one second, and the PS’ strategy of drawing attention to the ‘winnable’ contest in Marseille to obscure the likely defeats in other cities blew up in their faces. The PS has no chance of winning Marseille on March 30; the focus is now on saving what can be saved, which is a fairly important task in its own right because what is saved on March 30 will be crucial for senatorial elections in the fall.

The FG, which won a very mediocre 7.1% in a city which was at one time one of the main strongholds of the PCF (and the north, the current 8th sector in particular, one of the safest PCF areas outside the Red Belt), will merge its lists with that of the PS. In the 8th sector, FG mayoral candidate Jean-Marc Coppola, a PCF regional councillor, won 10.8%, the FG’s best result.

Independent left-leaning and anti-establishment lists led by Pape Diouf, the former president of the Olympique de Marseille (OM) football club from 2005 to 2009, won 5.6% (6.4% for Diouf himself in the 7th). Pape Diouf’s lists included members of civil society, civic associations and EELV dissidents who opposed EELV’s alliance with the PS. Pape Diouf’s lists, although left-leaning, attacked the clientelism of both PS and UMP and presented itself as a civic, apolitical opposition to the political establishment. However, many of Diouf’s candidates, including Sébastien Barles (EELV) in the 1st sector, were hoping that they would reach a merger agreement with the PS lists after the first round. Instead, Diouf announced that there would be no merger and refused to endorse anybody. His decision, apparently taken autocratically, irked many of his supporters.

In the 3rd sector, where we had been told to expect a close battle between the PS and UMP, the PS list led by junior minister Marie-Arlette Carlotti is 17 points behind the UMP list of incumbent mayor Bruno Gilles. In the 1st sector, which is Patrick Mennucci’s sector and was a PS gain in 2008, Mennucci himself find himself trailing UMP deputy Dominique Tian by more than 11 points and must save his own seat. The PS only leads in the 8th sector in Marseille’s northern suburbs, where the PS list led by incumbent mayor and senator Samia Ghali (Mennucci’s main rival in the 2013 primary) topped the poll – but only narrowly, with 31.7% against 27.6% for the FN. In the 7th sector, the other northern sector, the PS list led by incumbent mayor Garo Hovsepian is trailing in third place, with 21.7% against 32.9% for the FN list led by FN mayoral candidate Stéphane Ravier and 27.8% for the UMP. In the 6th sector, another sector presented as a ‘swing’ sector and potentially winnable for the PS, the PS list led by general councillor Christophe Masse is in even worse shape: in third, with a mere 16.6% against 35.2% for the UMP’s Roland Blum-Valérie Boyer tandem and 25.9% for the FN. Robert Assante, the incumbent ex-UDI/ex-UMP mayor of the 6th sector, won 13.4% running a dissident list. Assante had left the UMP after he was pushed aside in favour of his enemy, Valérie Boyer, for a seat in the National Assembly. His list has merged with that of the UMP; according to this deal, Assante will retain his mayoral position, something which in turns alienates Boyer, who had been promised that job.

The most shocking result is from the 2nd sector, a very poor left-wing stronghold. The left was divided between the PS-EELV list led by Eugène Caselli, the PS president of the urban community (Marseille Métropole Provence, MPM) and a PRG list led by incumbent mayor Lisette Narducci, a close ally (many would say tool) of the controversial and highly corrupt PS president of the general council, Jean-Noël Guérini (who retains significant weight in Marseille politics, as some kind of Godfather; he’s especially strong in the 2nd sector, since he is the general councillor for the canton of Marseille-Les Grands-Carmes, the family seat since 1951). The UMP list placed first with 24.2%, but the Narducci list placed second, with 23.8%, against only 17.5% for Caselli’s official PS list.

Guérini, who was the PS mayoral candidate back in 2008, is angry at the way the PS has disowned and denounced him after he was hit by several corruption and nepotism scandals. He is especially at odds with Patrick Mennucci (and Carlotti), two erstwhile allies from 2008 who have since turned into the strongest opponents of the ‘Guérini system’ and focused the PS campaign on ethics and fighting corruption. In the PS primary, Guérini was widely suspected of using a bit of his machine to favour Samia Ghali, who disingenuously ran as the local ‘anti-system’ candidate – in the second round against Mennucci, Ghali saw her biggest gains in the 2nd and 3rd arrondissements (the 2nd sector) – Guérini’s stomping grounds. Since then, Guérini was said to be covertly backing Gaudin to take his revenge on Mennucci.

After the first round, Guérini’s marriage of convenience with the UMP and Gaudin was made official. On March 25, Gaudin announced that he had reached an agreement with the PRG (=Guérini’s tools) and Narducci in the 2nd sector, merging the UMP and PRG lists with Narducci taking first place on the new list (with the promise of retaining her mayoral position in case of victory). Narducci claimed that she merged her list to ‘fight the FN’ and said that the PS had refused her proposal for negotiations. However, as Caselli argued, the argument doesn’t hold: the 2nd sector is in no danger of falling to the FN; the PS is furious, denouncing a rogue and unnatural alliance with the UMP. For the UMP, the alliance is perhaps not the best from a PR standpoint but it doesn’t care – it’s great Machiavellian politics. Gaudin allies with Guérini to perpetuate his clientelist system in alliance with the other political boss of the department; in Marseille, a likely UMP-PRG victory in the second sector does a lot to guarantee an absolute majority in the municipal council for Gaudin and it throws more wrenches in the PS’ desperate post-first round strategies. The PS campaign is trying to seize on the UMP-Guérini alliance, now focusing its campaign on an appeal to vote against the ‘Gaudin-Guérini system’ and corruption on March 30. The alliance of an old and increasingly tired mayor with a very mixed record (Marseille is an increasingly socially divided and highly stratified city with huge violence, drugs and crime problems in the poor north; unemployment is high) with a corrupt politician may also play into the FN’s hands, and help push some dismayed right-wingers to vote for the FN in the second round.

To explain the PS’ surprise disaster in the first round, one good explanation might be turnout: it was only 53.5% in the city as a whole, with turnout below 50% in the 2nd, 7th and 8th sectors (the most left-wing sectors). According to a post-election Ifop poll, there may have been a strong partisan difference in turnout: it reports that only 40% of Hollande’s first round voters from 2012 voted compared to 65% of Sarkozy’s voters and 78% of Le Pen’s voters. Comparing raw votes in 2012 to 2014, Mennucci’s lists won only 53k against 104,818 for Hollande in April 2012. Ravier and Gaudin also lost votes compared to Le Pen and Sarkozy, although Gaudin remarkably only lost 4,000 or so from Sarkozy’s April 2012 total. Therefore, one explanation for the PS’ result might be major demobilization of the PS base since 2012, combined with the superior mobilization of the UMP and FN electorate.

An Ifop study at the precinct level confirmed the poll findings: there was a positive correlation between support for Hollande in April 2012 and abstention, with 41% abstention in polls where Hollande was the weakest and 63% abstention where he was the strongest. Abstention also increased (since 2012) most where Mennucci’s losses on Hollande’s 2012 showing were the heaviest. Some other Hollande voters who did turn out voted for Pape Diouf’s lists, which won 13% on average in polls where Hollande had won over 50% in April 2012, compared to only 3.7% in polls where Hollande had won less than 20% in April 2012. Again, Diouf’s support was strongest where the PS’ loses from 2012 were the most pronounced. In contrast, the study found no correlation between decline for the PS and increase for either the UMP or FN (since 2012).

Libé also mentions a potential casting error in the 7th sector: pushed by the area’s (corrupt) deputy, Sylvie Andrieux (ex-PS), the sitting PS mayor Garo Hovsepian (Andrieux’s suppléant) was pushed to run for reelection while Christophe Masse, a powerful PS general councillor whose electoral base is in the 7th sector, was pushed to run in the 6th sector, where his base is much weaker. Andrieux was allegedly unwilling to see Masse, a potential rival for her seat, establish a rival foothold. In the 3rd sector, we may also be led to believe that Carlotti suffered from her direct association with the unpopular government (although she’s a low-profile junior minister).

There is a major north-south social divide in Marseille, a poorer city with much more visible and dramatic social divides than either Paris or Lyon. According to a 2014 study, the poverty rate ranges from 9% (8th arrdt) to 55% (3rd arrdt) in Marseille, whereas it ranges from 9% to 21% in Lyon and 7% to 25% in Paris. Marseille’s northern suburbs (quartiers nord) are predominantly poor, with very high unemployment rates, high immigrant population, major social problems, severe challenges with violence and crime and the concentration of the population in densely populated cités which sprung up under Defferre’s administration as the city struggle to accommodate a growing population from the post-1962 exodus of pieds noirs from Algeria and later North African immigration. The southern suburbs, particularly hilly neighborhoods lining the Mediterranean (in the 7th and 8th arrdt), are far more affluent and privileged. Jean-Claude Gaudin’s solid personal electoral base is in the 4th sector where he was reelected, as in 2008, by the first round with 50.1% for his UMP list. The 4th sector includes the 6th arrondissement, the old central bourgeois arrondissement which does have a left-leaning bobo element (the Cours Julien area in Notre-Dame-du-Mont) and the 8th arrondissement, a seafront arrondissement whose northern half (Le Périer, La Plage, Saint-Giniez) is the most affluent part of the city and also the UMP’s strongest area.

The 1st sector presents an interesting contrast between its two components, the 1st and 7th arrondissements. The 7th includes Le Roucas-Blanc, a very affluent seaside neighborhood which is solidly UMP; the 1st is a poor (43% poverty) multicultural rundown inner-city area with unemployment at about 30% and about 30% of the population without any diploma; although it does include some gentrified areas. The 1st is Mennucci’s electoral base, while the 7th is in Dominique Tian’s constituency.

The FN won its best results in the 5, 6, 7 and 8 sectors – taken as a whole, they cover the whole outer eastern half of the city – the northern suburbs but also the east of the city (Vallée de l’Huveaune). The areas where the FN tends to do best in Marseille are lower middle-class areas which are rather low-income, have low levels of education, blue-collar employment but don’t necessarily have record-level unemployment and poverty; they have a substantial foreign/immigrant minority, but not a majority. These are, especially the 7th sector, ‘settled’ area with relatively little mobility (very few recent settlers) and a population which has lived in the area for 10 years or more. More often than not, these areas aren’t cités (many of them in a ZUS) with HLM towers, but rather neighboring residential suburban neighborhoods – banlieues pavillonnaires (residential suburbs with individual houses). In fact, in a lot of cases, the precincts covering the largest cités (which have the largest immigrant population) tend to be solidly left-wing with very low FN support. According to these maps, the FN vote reached record levels in some of these northern residential suburbs – over 35-40% in places such as Château Gombert (13th) and Verduron (15th) – lower middle-class areas, comparatively affluent compared to other neighborhoods in the north. These are neighborhoods were a lot of individual houses are now gated, as noted in this article.

In the northern suburbs, the left (PS in particular) is hegemonic in most of the large cités (ZUS) – places with extremely high unemployment (sometimes over 40%), very low education levels (less than 5% with a BAC+3), the highest levels of poverty (over 55% in the 3rd arrdt, 44% in the 2nd and 15th, 43% in the 1st and 42% in the 14th) and a very large immigrant population. In some cases, a strong PS vote may be accompanied by a strong FN vote, but in general, the strongest precincts for the left are generally very weak for the FN – in the aforecited link with maps, the FN apparently polled less than 10% in the HLM cités of Verduron (15th). The 8th sector, the only one where the PS came out ahead on March 23, includes the core of the quartiers nord – in the two arrondissements of this sector, 65% and 56% respectively live in a ZUS. These areas, including former villages such as Saint-André and Saint-Henri (16th arrdt), used to be working-class (tileries, Marseille’s harbour etc) areas, and consequently were PCF strongholds until not so long ago. Samia Ghali, the incumbent PS mayor of the sector, has a very strong political machine in those neighborhoods. In the 2nd sector, which includes Marseille’s two poorest arrondissements, the PS, as noted above, faced crippling competition from the PRG (Guérini stooge) incumbent, who likely received the full support of Guérini’s networks – Guérini is the general councillor for the canton of Marseille-Les Grands-Carmes since 1982 (replacing his father, who won the seat in 1951), which covers the bulk of the 2nd arrondissement.

In the 3rd sector, the PS had been counting on the illusory bobo vote which would swing the sector to the left. The 3rd sector, the key swing sector, is mix of downtown affluent and bobo middle-class area (Le Camas in the 5th, Cinq Avenues in the 4th) with more suburban right-leaning areas (with a significant FN base). The 5th arrondissement has seen a large influx of out-of-town residents, making it a highly mobile area. Indeed, the area has seen gentrification with a highly mobile young population settling in these accessible downtown areas; but there’s also a large older population, and Marseille’s (small) bobosphere is spread out of the 1st, 6th, 5th, 4th and even 7th arrondissements. The Cours Julien, often cited as Marseille’s main bobo drag, is in the 6th arrondissement (although it’s drowned by the UMP bourgeois areas, the particular bobo part of the 6th is solidly on the left and Mennucci likely did well there). The phenomenon may also have been overstated: Marseille remains a city famous for its social problems and high poverty, and the influx of a few out-of-towners doesn’t change the social reality… but the media would never let reality ruin a good story.

The UMP will hold Marseille on March 30. At first, there was a chance that Gaudin might have fallen short of an absolute majority, but that would require a PS victory in both the 1st and 2nd sectors, which now seems rather unlikely given the UMP-PRG alliance in the 2nd. The focus in Marseille will now focus on individual races: in the 1st sector, will Mennucci be able to save his own seat? In the 2nd sector, will Narducci’s voters follow her into the alliance with the UMP? In the 7th sector, finally, will Stéphane Ravier, ahead in the first round, win the triangulaire? There was heavy pressure on Hovsepian (PS) to withdraw because he placed third and the ‘danger’ of the FN victory in the sector – most pressure came from hypocrites in the UMP although some in the PS (agriculture minister Stéphane Le Foll) also called on the PS list to withdraw. If the transfers from the FG are good, and Diouf’s voters split in favour of the left, the PS still has a chance at holding the sector. The FN, as always, has little reserves and faces the historical tendency for the FN’s vote to decline somewhat in triangulaires. Will this time be different?

Lyon

| Arr. | PS-PRG* | UMP-UDI | FN | FG | EELV | Centre | DVD | DVG | LO | OTH |

| 1 | 25.94 | 19.12 | 6.18 | 33.45 | 11.27 | 3.1 | 0.91 | |||

| 2 | 27.22 | 47.12 | 11.52 | 4.84 | 6.05 | 3.23 | ||||

| 3 | 38.63 | 28.01 | 12.36 | 5.41 | 9.79 | 4.64 | 1.12 | |||

| 4 | 34.26 | 26.46 | 8.56 | 10.02 | 11.87 | 2.84 | 1.93 | 0.83 | 3.1 | |

| 5 | 36.29 | 35.65 | 11.31 | 4.58 | 8.16 | 3.03 | 0.93 | |||

| 6 | 26.79 | 50.06 | 10.41 | 3.13 | 6.19 | 3.4 | ||||

| 7 | 38.81 | 23.84 | 13.04 | 7.75 | 10.87 | 3.62 | 0.89 | 1.14 | ||

| 8 | 40.30 | 23.2 | 18.44 | 5.43 | 7.73 | 3.16 | 1.7 | |||

| 9 | 45.67 | 22.10 | 13.78 | 5.61 | 7.53 | 3.66 | 1.62 |

In Lyon, the incumbent PS mayor Gérard Collomb is seeking reelection for a third term. After a massive landslide in 2008 which saw him effectively win by the first round, his results in 2014 are not as remarkable but his third term remains a lock. Collomb, in keeping with Lyon’s noted propensity for centrist and moderate mayors and politics, is a good fit for the city – he’s on the right of the PS, and has criticized the government on some issues. He has good relations with right-wing mayors in the Grand Lyon, and his landmark project to transform the Grand Lyon urban community into a de facto department will be going ahead in 2015. Although the city likes moderate politicians, the MoDem has been weak and was divided this year – Eric Lafond, a former member of the MoDem excluded from his party, ran centrist lists in every arrondissement but won only about 3%.

In the first round, Collomb’s PS lists topped the poll in all but three arrondissement, two of which (the 2nd and the 6th) are very affluent strongholds of the right. Indeed, in the 6th arrondissement, the most bourgeois arrondissement, the UMP list led by Dominique Nachury won outright with 50.1% against 26.8% for the PS (a major drop from the PS’ 43.3% in the 2008 landslide). In the 2nd, a central arrondissement on the Presqu’île, the UDI-led list won 47.1% against 27.2% for the PS.

The PS’ best results came from the 8th and 9th arrondissements, with 40.3% in the 8th and 45.7% for Collomb’s own list in the 9th. The 9th is an old industrial zone on the outskirts of the city; it includes La Duchère, a large low-income and ethnically diverse cité on the limits of the city (unemployment is over 30%, about 30% are immigrants and the area is classified as a ‘zone urbaine sensible’ or ZUS). The 8th, at the other end of the city, is also an old working-class area, with two large ZUS/cités (États-Unis and Mermoz) and other poorer peripheral neighborhoods.

It is also the FN’s strongest arrondissement, especially the poorer areas which are outside but close to the ZUS (which have significant immigrant populations); with 18.4%, the FN list led by the mayoral candidate and FN regional councillor Christophe Boudot is qualified for the runoff. The FN outperformed Marine Le Pen in every arrondissement; in 2010, she had only broken 10% in the 8th and 9th, peaking at 14% in the 9th.

The closest battle will be in the 5th, where the PS (36.3%) lead over the UMP (35.7%, list led by its mayoral candidate, Michel Havard). On the west of the city, the 5th includes the Vieux-Lyon (the city’s historic core), the Fourvière hill and church but also residential suburbs – both middle-class and lower-income HLMs. It voted for Sarkozy in 2012, with a distinctive split between the suburban outskirts (for Sarkozy, minus the lower-income HLMs for Hollande) and the urban area (for Hollande). With the PS and EELV (8.2%) lists merging, the PS should retain this key arrondissement. In the 3rd arrondissement, which was gained by the PS in 2008, the PS has a ten point lead in the first round over the UMP.

On the Presqu’île of Lyon, the left-wing stronghold of the 1st arrondissement showed interesting results. The 1st is centered on the Pentes de la Croix-Rousse (les Pentes), a formerly poor working-class area (famous particularly for its silk workers) which has since been extensively gentrified and is now a bustling cosmopolitan, young, professional (many journalists, artists, academics, young cadres etc) and highly-educated ‘bobo’ area. The incumbent ex-PS mayor Nathalie Perrin-Gilbert, who left the PS in 2013, ran for reelection in alliance with the FG. She placed first, with 33.5% against 25.9% for the PS. Like in Paris, the PS and FG found no agreement in Lyon, so the FG list in the 1st and 4th arrondissements (the 4th includes the similarly bobo Croix Rousse, but the right is stronger because it includes some wealthier and older areas in the west) are maintaining themselves in the runoff; in the 1st, the PS list is now led by the first round EELV candidate. If there is one interesting contest to follow in Lyon on March 30, it would be the battle of the lefts in Lyon-1.

Toulouse

Jean-Luc Moudenc (UMP-UDI-MoDem) 38.19%

Pierre Cohen (PS-PCF-PRG-MRC)* 32.26%

Serge Laroze (FN) 8.15%

Antoine Maurice (EELV) 6.98%

Jean-Christophe Sellin (PG-FG) 5.1%

Christine de Veyrac (UDI diss) 2.45%

Élisabeth Belaubre (Cap21) 2.42%

Jean-Pierre Plancade (DVG) 2.12%

Ahmad Chouki (EXG) 1.67%

Sandra Torremocha (LO) 0.63%

The race in Toulouse, a left-leaning city which was governed by the right between 1971 and 2008, is a rematch of the 2008 election between then-mayor Jean-Luc Moudenc, now a UMP deputy for a constituency covering part of the city (and a few of its affluent UMP-voting suburbs) and Pierre Cohen, the PS candidate who narrowly won (with 50.4%). Cohen now has the advantage of incumbency and the city’s strong bias for the left (62.5% for Hollande in May 2012), which means that in such a climate against such a strong candidate, he has a fighting chance. But the results of the first round put him in a weaker position than was expected prior to the first round. Firstly, he trails the UMP by nearly 6 points. The merger with Antoine Maurice’s EELV list (7%) and the assumption that EELV’s votes will transfer well to him (a reasonable assumption, in my mind, but nothing precludes a surprisingly bad transfer to the PS) helps him out and tightens the contest. Transfers from the PG list, which won 5.1%, might not be as good because there was no merger between the PS and PG lists. On the right, Moudenc can count on a solid chunk of the first round FN vote (but not all of it) as well as nearly all of UDI MEP Christine de Veyrac’s tiny 2.5%.

Two polls have come out after the runoff, and they confirm one thing: the runoff is very tight and up in the air. CSA had Cohen ahead of Moudenc with 50.5%, while Ifop had Moudenc ahead with 50.5%. A repeat of the 2008 photo-finish appears to be the horizon.

Nice

Christian Estrosi (UMP-UDI)* 44.98%

Marie-Christine Arnautu (FN) 15.6%

Patrick Allemand (PS-EELV-MRC) 15.25%

Olivier Bettati (DVD) 10.13%

Robert Injey (FG) 5.38%

Philippe Vardon (Nissa Rebela) 4.44%

Jacques Peyrat (DVD) 3.69%

Michel Cotta (EXD) 0.63%

Very little suspense in Nice, where the popular incumbent Christian Estrosi (UMP), first elected in 2008, will be handily reelected – although it will be in the second round rather than by the first round. Nice nowadays is a right-wing stronghold, with 60.3% for Sarkozy in May 2012 (little indicating that the PCF was once a major force in Nice); the city’s population is significantly older than most other major cities (especially compared to young cities like Toulouse) and largely middle-class (employees, shopkeepers, intermediate grade professionals). The FN also has a long history in the city, which has been a base for the far-right since 1960s and the influx of pied noirs refugees from North Africa to the region. In the recent years, however, the FN’s support has been less impressive, with a portion of the FN’s old right-wing petit bourgeois electorate staying with Sarkozy’s UMP after 2007. In 2012, Marine Le Pen nevertheless won 23% (but that was down from her father’s 26.8% in 2002). In this election, the FN, which won a paltry 4% in 2008, was interested in a strong candidate but it had trouble finding one (it settled on Marie-Christine Arnautu, who had Jean-Marie Le Pen’s blessing) and the campaign faltered in the face of Estrosi’s popularity and his focus on criminality and security issues (Estrosi has a strong national profile on those issues, and finds himself on the right of the UMP as far as crime/immigration is concerned) which likely drew some FN voters. Arnautu nevertheless placed second, albeit with a mediocre result, while Estrosi’s result was over 10 points better than Sarkozy’s first round result in 2012. The left did very poorly, with only 15.3% for a PS-EELV list (and 5.4% for the FG, whose list hasn’t merged with that of the PS), down from 22% for Hollande in April 2012 and for Allemand’s list in 2008 (which also faced a dissident list, which had won 6.5%). On the right, Olivier Bettati, the dissident UMP general councillor for Nice-8, did rather well. Bettati is a former adjoint au maire, but his relations with Estrosi have always been quite cool and they’re now frigid (he is maintaining his list in the runoff). Another right-wing, however, had less success: Jacques Peyrat, a former FN deputy and the former mayor of Nice (1995-2008) who was defeated by Estrosi in 2008, won only 3.7% – he had taken 23.1% in 2008. Peyrat, who had allied with his former colleagues in the FN in 2011 and 2012, now was left all alone without any partisan support. On the far-right, Philippe Vardon, the leader of the local extremist Nissa Rebela party, a regionalist and far-right (neo-fascist, skinhead type) party, won 4.4%.

Estrosi will glide to victory in the second round, with a huge majority.

Nantes

Johanna Rolland (PS-PCF-PRG-UDB)^ 34.51%

Laurence Garnier (UMP-UDI-PCD) 24.16%

Pascale Chiron (EELV) 14.55%

Christian Bouchet (FN) 8.14%

Sophie Van Goethem (DVD) 5.59%

Guy Croupy (PG-Alternatifs-GA-NPA) 5.04%

Pierre Gobet (DVD) 4.3%

Xavier Bruckert (MoDem-UDI diss) 2.1%

Hélène Defrance (LO) 1.16%

Arnaud Kongolo (Ind) 0.46%

Nantes has been governed by the PS since 1989, and current (soon to be former?) Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault was mayor between 1989 and 2012. The PS had already gained Nantes in 1977, ending 30 years of right-wing rule (but CNIP mayor André Morice, from 1965 to 1977, governed with an anti-Gaullist and anti-communist alliance including centre-right and Socialists); the shift followed the general shift of Brittany and the inner west from Christian democratic centre-right to moderate centre-left – a movement which was spearheaded by urban areas, and followed only later by more suburban and rural areas (except those rural areas already on the left prior to the 1970s). Nantes has since become a left-wing stronghold, with 61.5% for Hollande in May 2012, although the UMP retains a resilient base in bourgeois areas to the west of the historic centre. In the first round, Johanna Rolland, a young (34-year old) première adjointe and protege of Ayrault, placed first with 34.5% against 24.2% for Laurence Garnier, a UMP municipal councillor who is also 34. In 2008, Ayrault had won reelection by the first round, with 55.7% against 29.9% for the UMP, but at the time, the Greens were on his list by the first round (as they had since 1995). EELV and the PS in Nantes have been quite at odds for the past few years, because of a disagreement of national proportions on the construction of a new international airport for Nantes (and Rennes) in Notre-Dame-des-Landes: the PS, spearheaded by Ayrault and most of the PS leadership nationally (except its left-wing), has strongly supported the project, while EELV has strongly opposed the project. The crisis has had repercussions on national politics, notably as it concerned the behaviour of EELV’s cabinet minister serving in a government which supports the airport. Running independently, EELV performed very strongly, with 14.6%. As these maps show, EELV did best in downtown central Nantes, a young and well-educated area with a high proportion of cadres (professionals). Its results, predictably, were far less impressive in the low-income cités located on the outskirts of the city.

The disagreements on Notre-Dame-des-Landes did not prevent EELV and PS from reaching a merger agreement quickly. The runoff will oppose the PS-EELV and the UMP, and the PS will win without much trouble.

Strasbourg

Fabienne Keller (UMP-MoDem) 32.92%

Roland Ries (PS)* 31.24%

Jean-Luc Schaffhauser (FN) 10.94%

Alain Jund (EELV) 8.52%

François Loos (UDI) 7.55%

Jean-Claude Val (FG) 3.96%

Tuncer Saglamer (Ind) 2.63%

Armand Tenesso (DVD) 1.08%

Pierrette Morinaud (LO) 0.73%

Élisabeth Del Grande (POI) 0.4%

Strasbourg, the Alsatian capital, is one of the UMP’s top targets and it has high hopes that Fabienne Keller, the UMP mayor of the city between 2001 and 2008, will take her revenge on PS mayor Roland Ries, who had defeated her in a landslide six years ago. Although Alsace is one of France’s most conservative regions, Strasbourg is often a pink ‘spot’ on the map – in 2007, Sarkozy won the city by a hair and Hollande won it with 54.7%. The city had traditionally been governed by centrists in the post-war era (from 1959 to 1989), but the PS held it between 1989 and 2001 and in the interwar years, when Alsatian politics were heavily influenced by a pro-German autonomist movement, Strasbourg had a Communist (autonomist) mayor between 1929 and 1935! In 2008, with the unfavourable national climate and public divisions within the UMP administration, Keller was steamrolled, trailing by ten points in the first round and losing 58 to 42 in the second round. This year, although Ries has the advantage of incumbency, and unlike the PS in 2001 and the UMP in 2008, no apparent divisions in his ranks, the cards have changed with the unpopularity of the PS government. In the first round, Keller came out narrowly ahead, with 32.9%, against 31.2% for the incumbent. Both are down from their 2008 results (although Keller improves on Sarkozy’s 27.5% in April 2012), but Ries especially so – down nearly 13 points. The runoff will be very tight. Keller has merged with the UDI list led by former cabinet minister and deputy François Loos, which won 7.6%, while Ries has merged with the EELV list, which won 8.5% (improving on the Greens’ 6.4% in 2008).

The bad news for the UMP in this extremely tight runoff is that it will be a triangulaire. The FN is usually weak in Strasbourg (11.9% in 2012), but with 10.9% this year, it narrowly surpassed the crucial 10% threshold. Although in such circumstances it is likely that the FN’s vote will drop somewhat in the second round (to 9% or so), with the defectors likely voting UMP (or PS, for a smaller share), the UMP’s dreams of reconquering Strasbourg might very well be thwarted by the FN’s qualification for the runoff. A poll by Ifop showed Ries leading Keller by 1 point, 46 to 45, with 9% for the FN. Ries wins 79% of Jund’s voters, Keller wins 82% of Loos’ voters and also 23% of the first round FN vote.

Rue89 Strasbourg has published excellent interactive maps by precinct. Fabienne Keller (UMP) won her best results in the north of the city, specifically the affluent central neighborhoods of L’Orangerie and Contades and the comfortable middle-class suburban neighborhood of Robertsau; in these areas, the UMP candidate won over 40% of the vote, in some cases 45-50%, in most precincts. The left has made gains in downtown Strasbourg, the result of ‘boboisation’ and gentrification – Ries won most polls in the Gare, downtown, Esplanade and Krutenau – these are predominantly young areas with large student populations (Esplanade, downtown), a large proportion of professionals, high levels of education but they also remained socially mixed areas, evidenced by the large proportion of social housing Esplanade and some poorer areas in the Gare area, a formerly working-class area close to the railway depot. Alain Jund won double digit results in the downtown, Gare and Krutenau; the FN is generally weak (predictably), but there remains substantial FN support in the more downtrodden precincts (Esplanade, Vauban) where social housing is dominant.

Both the UMP and PS split roughly equal in the Neudorf, a populous residential area south of downtown, traditionally lower middle-class or working-class but which has seen gentrification, bringing a younger and more educated population. The FN has substantial support in the poorer parts of the Neudorf. Further south, Ries won strong numbers in the cités of the Neuhof and Meinau, low-income working-class neighborhoods; but the UMP and FN were strong in the suburban residential areas surrounding these cités – the FN is particularly strong in the Neuhof, where its candidate won over 20% in numerous polls outside the cités – lower middle-class suburban areas with comparatively low unemployment but a low-income population with low levels of education and CSP- jobs (employees, workers). These are also in proximity to the cités, which have a large Muslim immigrant population (the halo effect of FN support).

Ries was also very strong in the cités on the western periphery of Strasbourg – with over 40% support in Hautepierrre, a large neighborhood of 1960s-era HLMs and social housing tracts for the working-class. Turnout in these areas is very low – below 40%, even 30%, in most cases. Ries also won most polls in the similarly low-income and working-class neighborhoods of Cronenburg Ouest, Koenigshoffen and Elsau; but, once again, he was defeated by the UMP and FN in the similarly low-income (marginally better off) but residential and white(r) suburban precincts. The FN won between 15 and 20% in parts of Elsau and Montagne Verte. In these kinds of neighborhoods, the left at all levels has lost support (while gaining in places such as the Neudorf and downtown).

It is also worth pointing out some very strong results in Hautepierre, Cronenburg and Elsau for Tuncer Saglamer, a ‘citizen’ candidate of Turkish descent (according to Rue89, he is known for ties to an organization which is supportive of the governing Turkish AKP). He won over 20% in Cronenburg, about 15% in Elsau and 10% in Hautepierre. Certainly, the candidate’s Muslim faith, shared with many inhabitants of these cités attracted many voters, dissatisfied with politics in general. Similar lists – listes citoyennes (citizens’ lists) – drawn from civil society in the banlieues have won some substantial support in other cities (especially in the 93), drawing on locals’ dissatisfaction with both left and right (and they won’t vote FN, for obvious reasons) and the sentiment that politicians in the PS take them for granted and use them as pawns in their electoral machines or for clientelist purposes (a very fair assessment).

Montpellier

Jean-Pierre Moure (PS-EELV-PRG-MRC)^ 25.27%

Philippe Saurel (DVG-PS diss) 22.94%

Jacques Domergue (UMP-UDI-MoDem) 22.72%

France Jamet (FN) 13.81%

Muriel Ressiguier (FG) 7.56%

Joseph Francis (UDI diss) 4.52%

Thomas Balenghien (NPA-FASE-PG diss) 2.05%

Maurice Chaynes (LO) 0.89%

Annie Salsé (POI) 0.24%

Montpellier, a young, professional and university city, is a left-wing stronghold – Hollande won 62.4% here in May 2012, and the PS has governed the city since 1977. However, this year, there is a highly contentious battle on the left for the mayor’s seat. Incumbent PS mayor Hélène Mandroux, described as a weak politician with little weight in metropolitan and regional politics and internal PS politicking, was forced to ‘retire’ despite her initial intentions to run again. Intervention from Paris ensured that she didn’t cause trouble. The official PS candidate is Jean-Pierre Moure, the current president of the agglomeration community who, in that position, gradually asserted his power over the local PS organization and rallied to his side most of the frêchiste Socialists – supporters of former mayor and regional president Georges Frêche, excluded from the PS in 2010 for anti-Semitic statements but who was reelected to the regional presidency in a landslide in 2010 (crushing an official PS list led by Mandroux in the first round) and who retained much weight and power in the PS in the Montpellier region until his death in October 2010. Moure, who is allied with EELV, very strong in Montpellier (18.9% in the 2008 runoff), faced a strong dissident candidacy – Philippe Saurel, a member of the governing majority considered close to interior minister Manuel Valls who had refused to participate in the primaries. In the first round, Moure came out ahead, with 25.3%, but Saurel placed a strong second with nearly 23%. Jacques Domergue, a former UMP deputy, placed third with a paltry 22.7% (which is, however, the right’s usual first round base in Montpellier). The FN is weak in Montpellier, with 13.7% for Le Pen in 2012, but 13.8% was enough for France Jamet, a FN regional councillor to qualify for the runoff.

The rivalry and bad blood on the left was enough to preclude any miraculous coming-together of the two PS lists. Despite calls from Ayrault, Valls, PS leader Harlem Désir and most of the PS leadership, Saurel has decided to maintain his list in the second round. The media, always looking for a scoop, is saying that this four-way runoff opens the door to a UMP gain on the back of the left’s divisions. While that cannot be ruled out, it looks fairly unlikely: with no FN reserves to fall back on because the FN is qualified as well, the UMP has little reserves except that of a UDI dissident who won 4.5%. The runoff will be tight, and again the UMP has an outside chance at sneaking up the middle to win, but it is hard to predict which of Moure, Saurel and Domergue will emerge as the winner.

An Ifop poll confirmed that the runoff is very close: it showed Saurel leading Moure by 1 point, 31 to 30, with the UMP in a threatening third at 26% and the FN stable at 13%.

Bordeaux

Alain Juppé (UMP-UDI-MoDem)* 60.94% winning 52 seats

Vincent Feltesse (PS-EELV) 22.58% winning 7 seats

Jacques Colombier (FN) 6.06% winning 2 seats

Vincent Maurin (FG) 4.59%

Yves Simone (Ind) 2.58%

Philippe Poutou (NPA) 2.5%

Fanny Quandalle (LO) 0.51%

Hollande won 57.2% in Bordeaux in May 2012, thanks to strong results in Saint-Michel (historically working-class, now increasingly hip and gentrifying young area, albeit with persistent poverty and high unemployment) and peripheral ZUS (La Bastide, northern Bordeaux Maritime etc), although the UMP retains, in national elections, a very strong base in Caudéran and Bordeaux’s western neighborhoods which are very affluent. But at the municipal level, it has been a Gaullist stronghold since 1947 – first under Jacques Chaban-Delmas, mayor from 1947 to 1995, and since 1995 with Alain Juppé. The PS has made big gains at the national level, most emblematically with Juppé’s defeat in a central Bordeaux constituency in the 2007 legislative elections to a little-known PS candidate, signaling a shift to the left in the well-educated and professional middle-class areas (downtown, Saint-Augustin, Saint-Genès). Nevertheless, the right has remained thoroughly dominant in municipal elections – since at least 1971, the election has always been decided in the first round. This year was no different. Juppé was reelected with 60.9%, which is the best result for the right since 1983, against only 22.6% for Vincent Feltesse, the PS president of the urban community (CUB). The PS’ result is down about 12 points from its performance in 2008, when it had won a respectable 34.1% against 56.6% for Juppé. The FN, weak in Bordeaux (8.2% in 2012), nevertheless was represented on city council between 1989 and 2008 thanks to first round victories for the UMP allowing it to win seats by winning over 5% of the vote. In 2008, it fell to only 2.6%. This year, with 6%, it regains a two-seat bench on the city council.

The UMP is also in a favourable position to regain control of the CUB, which has been presided by the PS since 2004 because of the PS’ control of most of Bordeaux’s largest suburbs (Mérignac, Pessac, Saint-Médard-en-Jalles, Cenon, Lormont etc). But, in addition to the big defeat in Bordeaux, the left lost a few small suburban communes to the right in the first round and it is in a difficult position against the UMP in the runoff in Pessac, the CUB’s third largest city with over 58,000 inhabitants. Alain Juppé, who already presided the CUB from 1995 to 2004, would likely be president of the CUB if the UMP wins control.

Juppé’s excellent result increases speculation about a potential presidential candidacy in 2017. Juppé is one of the most popular politicians in France, with a 52-35 favourable rating in the Ipsos March 2014 barometer, with 76% favourable opinions with UMP sympathizers (ranking second behind Sarkozy) and 47% favourable opinions with PS sympathizers (making him the most popular right-wing politician on the left). Juppé has a moderate, pragmatic and consensual image; he remained neutral in the UMP’s 2012 civil war and escaped unharmed and he has a positive record as mayor of Bordeaux. Juppé ranks a very distant second behind Sarkozy (but miles ahead of both Copé and Fillon) when UMP sympathizers are asked their favourite 2017 presidential candidates.

Lille

Martine Aubry (PS-PRG-MRC)* 34.86%

Jean-René Lecerf (UMP-UDI-MoDem) 22.73%

Éric Dillies (FN) 17.15%

Lise Daleux (EELV) 11.08%

Hugo Vandamme (FG) 6.17%

Alessandro Di Giuseppe (Church of the Most Holy Consumption) 3.55%

Jacques Mutez (DVG) 1.88%

Nicole Baudrin (LO) 1.47%

Jan Pauwels (NPA) 1.1%