Category Archives: Croatia

EU 2014: Austria to Finland

In the next few posts, this blog will be covering the detailed results of the May 22-25 European Parliament (EP) election in the 28 member-states of the EU. As was argued in my introductory overview, the reality of EP elections is that they are largely fought and decided over national issues and the dynamics of EP elections are similar to those of midterm elections in the US. The results of this year’s EP elections, despite the EU’s attempts to create the narrative of a pan-European contest with ‘presidential candidates’ for the presidency of the Commission, confirmed that this is still the case. Turnout remained flat across the EU, and while some pan-European trends are discernible – largely an anti-incumbent swing which is nothing new or unusual in EP elections, with a secondary swing to anti-establishment Eurosceptic parties in most but not all member-states – the fact of the matter is that the changes in the makeup and strength of the parliamentary groups in the new EP owe to individual domestic political dynamics in the 28 member-states.

These posts will likely come in alphabetical order. Some countries will be covered by guest posters who have generously accepted to help out in this big task, contributing some local expertise.

These posts do not include, generally, descriptions of each party’s ideology and nature. For more information on parties, please refer to older posts I may have written on these countries on this blog or some excellent pre-election guides by Chris Terry on DemSoc.

In this first post, the results in countries from Austria to Finland.

Austria

Turnout: 45.39% (-0.58%)

MEPs: 18 (-1)

Electoral system: Preferential list PR, 4% threshold (national constituency)

ÖVP (EPP) 26.98% (-3%) winning 5 seats (-1)

SPÖ (S&D) 24.09% (+0.35%) winning 5 seats (nc)

FPÖ (NI/EAF) 19.72% (+7.01%) winning 4 seats (+2)

Greens (G-EFA) 14.52% (+4.59%) winning 2 seats (+1)

NEOS (ALDE) 8.14% (+8.14%) winning 1 seat (+1)

EU-STOP 2.76% (+2.76%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Europa Anders (GUE-NGL) 2.14% (+2.14%) winning 0 seats (nc)

REKOS (NI/MELD) 1.18% (+1.18%) winning 0 seats (nc)

BZÖ (NI) 0.47% (-4.11%) winning 0 seats (-1)

Austria’s two traditional parties of government – the centre-right Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) and the centre-left Social Democrats (SPÖ) both performed relatively poorly, in line with the general long-term trend of Austrian politics since 2006 or the 1990s. The last national elections in September 2013 ultimately saw the reelection of Chancellor Werner Faymann’s SPÖ-ÖVP Grand Coalition, although both the SPÖ and ÖVP continued their downwards trend and suffered loses, hitting new all-time lows of 26.8% and 24% respectively. The SPÖ and ÖVP, having dominated and controlled Austrian politics for nearly the entire post-war period, have gradually seen their support diminish considerably from the days of the stable two-party system which existed until the late 1980s. The ‘Proporz’ power-sharing system – the division of posts in the public sector, parastatals and government between the two major parties in the context of a pillarized political system – eroded ideological differences and created a fairly corrupt and nepotistic system of patronage and political immobilism. Austria’s economy is doing fairly well and the country is a haven of stability, but there’s no great love for its government. The SPÖVP Grand Coalition, which has governed Austria since 2006, could perhaps best be described as ‘boring’ – a stable, consensual and moderate government which ‘stays the course’ with rather prudent economic policies (mixing austerity and Keynesian job-creation incentives) and a pro-European outlook. There have been controversies and scandals to weaken the governing parties’ support and make them vulnerable to anti-corruption politics, but no crippling scandals. In turn, that means that it can be described by critics as ineffective, stale and unresponsive to voters’ concerns.

Four parties benefited from the SPÖVP’s relative unpopularity in 2013. Two old ones: Heinz-Christian Strache’s far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ), a strongly Eurosceptic and anti-immigration populist party with a strong ‘social’ rhetoric advocating both interventionist and neoliberal economic policies (tax relief, rent reduction, higher minimum wage, millionaires’ tax, more generous pensions, tax breaks for SMEs, tax cuts for the poorest bracket, reducing bureaucracy); and the Greens, a left-wing party focused on environmental questions and government ethics. Two new ones: NEOS, a new pro-European right-leaning liberal party founded by a former ÖVP member in 2012, which has taken strongly pro-European (federalist) views combined with fairly right-wing liberal economic stances (tax cuts, a flatter tax system, pension reform, reducing bureaucracy, macroeconomic stability); and Team Stronach, a populist Eurosceptic (anti-Euro) right-wing (liberal to libertarian economic views) party founded by Austrian-Canadian businessman Frank Stronach. The FPÖ won 20.5%, the Greens won 12.4%, Stronach won 5.7% and NEOS surprised everybody by winning 5% (taking 9 seats). The FPÖ was decimated by its participation in the controversial black-blue government with the ÖVP between 1998 and 2005, and further weakened by the FPÖ’s famous leader Jörg Haider walking out of the party to create the BZÖ in 2005. But since 2006, it has gradually recovered lost strength, regaining its traditional anti-establishment, anti-EU and anti-immigration rhetoric and base of protest voters. In the 2013 election, the BZÖ lost all its seats, having been fatally wounded by Haider’s death in a car crash in 2008 (a short while after Haider’s BZÖ had won 11% at the polls in 2008) and infighting after his death. Since the 2013 election, Stronach’s party has, for all intents and purposes, died off: the party’s underwhelming showing at the polls in September 2013 led to internal dissent against the boss (Stronach) while Stronach lost interest in his pet project. Stronach has since gone back to Canada, leaving his party’s weak caucus to fend for itself without their boss and his money. The party barely polls 1% in the polls, and it decided not to run in the European elections or a state election in Vorarlberg later this year.

The SPÖ and ÖVP, under Chancellor Faymann and Vice Chancellor Michael Spindelegger, renewed their coalition for a third successive term with basically the same policy agenda and dropping the contentious points on their platforms which the other party disagreed with. This was greeted with disinterest or opposition by the public, and Strache’s FPÖ has continued climbing in polls. The far-right, ironically one might add, has seemingly cashed in on the Hypo Group Alpe Adria bank troubles. The bank, owned by Haider’s far-right Carinthian government until 2007, has been at the heart of a large scandal involving bad loans, kickbacks to politicians and a banking expansion gone terribly wrong. The bank was sold by the Carinthian government to a Bavarian bank in 2007, before the Austrian federal government nationalized it in 2009. The embattled lender has required the federal government to pump out large sums of bailout money (taxpayers’ money) to prop it up, and the situation has barely improved. In February 2014, the SPÖVP government decided to set up a bad bank, transferring €19 billion of troubled assets to wind it down fully. Austrians have already paid about €5 billion to help the bank, and the majority of voters want to bank to go bankrupt rather than footing the costs of winding it down (the government’s plan would increase, albeit temporarily, the debt and deficit). Although many agree that it was Carinthia’s FPÖ government which created the Hypo mess in the first place, the FPÖ’s support increased in the polls this spring when the bank was a top issue. The FPÖ is generally first or second in national opinion polls, polling up to 26-27% while the ÖVP and SPÖ are in the low 20s.

EP elections are, however, a different matter. In the last few elections, the ÖVP has generally done better than in national polls and the FPÖ hasn’t done as well. In 2004 and 2009, the FPÖ was weakened by competition from the Martin List – an ideologically undefined anti-corruption and soft Euro-critical movement led by ex-SPÖ MEP Hans-Peter Martin, who won 14% in 2004 and 17.7% in 2009 (electing 2 and 3 MEPs respectively). Since 2009, Martin lost his two other MEPs – one joined the ALDE and ran for reelection as the right-liberal BZÖ’s top-candidate while the other ran as the top candidate for the European Left-aligned Europa Anders alliance (made up of the Pirate Party and the Communist Party), and his personal transparency and probity has been called into question. Martin, polling only 3%, did not run for reelection. The FPÖ was drawn into a significant crisis when Andreas Mölzer, MEP and top candidate from the FPÖ’s traditionalist far-right and pan-German wing, commented at a round-table that the Nazi Third Reich was liberal and informal compared to the ‘EU dictatorship’ and called the EU a ‘negro/nigger conglomerate’ (negrokonglomerat). Mölzer apologized for the ‘nigger’ comments but did not back down on the Third Reich comparison, and Strache initially accepted his apology. But there was strong political pressure from other Austrian politicians and parts of the FPÖ for Mölzer to step down as FPÖ top candidate, which he did on April 8. Harald Vilimsky, an FPÖ MP close to Strache, replaced him. Ironically, on April 8, the BZÖ’s initial top candidate, Ulrike Haider – the daughter of the late Carinthian governor – stepped down as the party’s top candidate. The FPÖ’s support in polls declined from 20-23% to 18-20% following the mini-scandal, before climbing back up to 20-21%.

The ÖVP, led by incumbent MEP and EP vice-president Othmar Karas, topped the poll with 27% of the vote, a result down 3% on the ÖVP’s fairly strong showing in 2009 (30%) and costing the party one seat in the EP. The SPÖ, which had performed very poorly in 2009 with only 23.7% (a result down nearly 10 points from 2004), barely improved its totals, taking a paltry 24.1%. In all, both coalition parties performed poorly at the polls. For the ÖVP, however, it was a strong performance compared to what it’s been polling in national polls – it has gotten horrendous results, barely over 20% and down to 18% in some polls; its leader, Vice Chancellor and finance minister Michael Spindelegger, even manages the relatively rare feat of being more disliked than the far-right’s leader. The ÖVP has been bleeding support to NEOS, the new right-wing liberal party which is attractive to ÖVP voters in their leader’s home-state of Vorarlberg but also high-income, well-educated urban centre-right voters. From 5% in 2013, NEOS has been polling up to 13-14% – the same range as the Greens.

The ÖVP’s stronger performance in the EP elections likely owes mostly to turnout. The ÖVP’s increasingly elderly and fairly rural electorate is far more likely to turn out in the EP election than the FPÖ’s potentially large but also fickle electorate of anti-EU protest voters who have lower turnout in low-stakes elections such as EP elections (and there was not much to mobilize a protest electorate to vote in an EP election this year). The turnout map shows the heaviest turnout from the rural Catholic ÖVP strongholds in Lower Austria (the Waldviertel and Mostviertel regions of the state are some of the strongest ÖVP regions in Austria, with the conservative party taking about 40% there this year), although turnout was also high in the traditionally Socialist state of Burgenland and SPÖ-leaning areas in Lower Austria’s Industrieviertel. In Vienna, the conservative-leaning districts had higher turnout than the working-class SPÖ/FPÖ battleground boroughs (53.7% turnout in ÖVP-leaning Hietzing and 34.8% turnout in the working-class district of Simmering).

SORA’s exit poll/post-election analysis showed an electorate which was more pro-EU than non-voters: 35% of voters expressed ‘confidence’ in the EU while only 18% of non-voters did so; 28% of voters expressed ‘anger’ in the EU compared to 35% of non-voters while an additional 19% of non-voters were indifferent towards the EU. 15% of non-voters thought the country should leave the EU; only 9% of actual voters thought likewise. Consider, on top of that, that of voters opposed to the EU, a full 60% supported the FPÖ while only 4% of pro-EU voters backed the far-right party. The FPÖ’s electorate is quasi-exclusively anti-EU/Eurosceptical, but it is this electorate which had the lowest turnout on May 25. As such, it is hard to consider this EP election as being an accurate portrayal of where public opinion/voting intentions for the next election stands at the moment.

Nevertheless, the FPÖ won a strong result, although it falls below the party’s 2013 result and falls far short of the FPÖ’s records in the 1996 and 1999 EP elections (27.5% and 23.4% respectively). The FPÖ gained about 7% from the 2009 election. According to SORA’s voter flow analysis, the FPÖ gained 26% of the 2009 Martin vote (130,000 votes), a quarter of the 2009 BZÖ vote (33,000) and 3% of 2009 non-voters (a still hefty 99,000 votes). It held 64% of its own vote from 2009, losing about 16% of its voters from five years ago to abstention and about 15k each to the ÖVP, SPÖ, Greens, NEOS and other parties. Geographically, the FPÖ performed best in Styria, placing a close second with 24.2% against 25.3% for the ÖVP – the FPÖ had won the state, where the state SPÖVP government is unpopular, in the 2013 elections. Unlike in the 2013 election, the FPÖ did fairly poorly in Graz (17.9%) but retained strong support in other regions of the state – both the conservative and rural southern half and the industrial SPÖ bastions of Upper Styria. In Carinthia, the FPÖ won 20.2%, gaining 13.5% since 2009, but not fully capitalizing on the BZÖ’s collapse in the old Haider stronghold – the BZÖ vote in the state fell by 19.6%, to a mere 1.4%. The SPÖ made strong gains in Carinthia, continuing the trend from the 2013 state and federal elections, winning 32.8% (+7.4%). In Vienna, the FPÖ won 18.2%, compared to 20.6% in 2013. Its best district remained the ethnically diverse and working-class Simmering, where the far-right party won 28.7% against 35.8% for the SPÖ.

The Greens performed surprisingly well, taking 14.5%, slightly better than the 12-13% they had received in EP polling. Since the 2009 election, the Greens have gained votes from non-voters (65k, 2%), Martin’s list (54k, 11%), the ÖVP (40k, 5% and the SPÖ (36k, 5%). These gains compensated for some fairly significant loses to NEOS, which took 12% of the Greens’ 2009 electorate (a trend observed in 2013) and to abstention, with 7% of the Greens’ 2009 supporters not turning out this year. The Greens performed best in Vorarlberg (23.3%, topping the polls in the districts of Feldkirch and Dornbirn) and Vienna (20.9%, topping the poll in their traditional strongholds in the central ‘bobo’ districts but also extending into gentrifying districts such as Hernals), and they were the largest party in the cities of Graz and Innsbruck.

Once again, the Greens’ support decreases with age (26% with those under 29, the SPÖ and ÖVP placed third and fifth respectively), increases with higher levels of education (31% with those with a university degree) and was at its highest with young females (32% with women under 29). There is a massive gender gap between young males and females; the former being the FPÖ’s prime clientele (33%) while the latter are left-leaning and liberal (only 16% for the FPÖ). The SPÖ and ÖVP, the two old parties, have been polling horribly with young voters, who prefer the fresher alternatives of the FPÖ (especially unemployed or blue-collar young males in demographically stagnant or declining areas, with low levels of qualification) or the Greens/NEOS (young, well-educated women and men with high qualifications in cosmopolitan urban areas and college towns). The SPÖ and ÖVP electorates are disproportionately made up of pensioners/seniors – the two parties won 34% and 35% of pensioners’ votes respectively.

NEOS, on the other hand, had a rather underwhelming performance: with 8.1% of the vote, the new liberal party on an upswing since 2013, only managed to win one MEP rather than the two they might have won if they matched their early polling numbers (12-14%). In the last stretch of the campaign, however, NEOS’ support fell to 10-11%, likely feeling the results of an ÖVP and Green offensive against the ‘NEOS threat’ – the Greens trying to depict NEOS as a right-wing liberal party. The party’s stances in favour of water privatization, waste management privatization and European federalism, which are unpopular topics in Austria, may have hurt them. Weak turnout with young voters, NEOS’ strongest electorate, may also have hurt them. NEOS polled best in Vorarlberg, where the party’s leader is from (14.9%) and Vienna (9.1%); in general, NEOS has urban support, largely from the same places where the Greens or the ÖVP find support (well-educated, younger, and middle-class professional inner cities). Demographically, NEOS’ support decreased with age (15% with those under 29) and generally increased with higher levels of education.

The BZÖ saw its support evaporate entirely, even in its former Carinthian stronghold. The party suffered from major infighting following Haider’s death, and the remnants of the party shifted to a right-wing liberal/libertarian and Eurosceptic platform which was a major flop in the 2013 elections. The BZÖ’s sole MEP, Ewald Stadler, from the far-right Haiderite/traditionalist wing of the party, was expelled from the party in 2013 after criticizing the right-liberal shift and the party’s 2013 campaign. He ran for reelection for The Reform Conservatives (REKOS), which won 1.2%. The BZÖ’s initial top candidate, Ulrike Haider, withdrew, and was replaced by Angelika Werthmann, an ex-Martin and ex-ALDE MEP. At this point, the BZÖ is likely to fully die off and disband.

On the left, the Austrian Pirates and Communists, which won only 0.8% and 1% in 2013, united to form an electoral coalition allied to the European Left, Europa Anders, led by Martin Ehrenhauser, an ex-Martin MEP. They managed a fairly respectable 2.1% of the vote.

Martin’s 2009 vote flowed mostly to the FPÖ (26%) and abstention (25%), but the SPÖ, ÖVP and Greens each received 11% of Martin’s 2009 vote and NEOS got 9% of them.

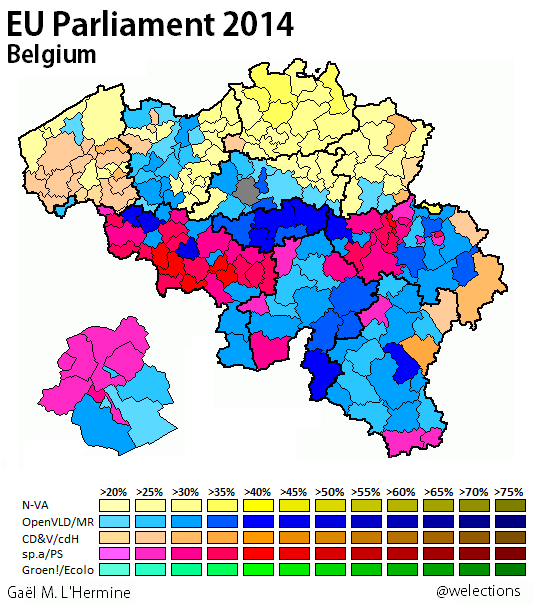

Belgium

Turnout: 90.39% (+0.75%) – mandatory voting enforced

MEPs: 21 (-1) – 12 Dutch-speaking college (Flanders), 8 French-speaking college (Wallonia) and 1 German-speaking college (German Community); voters in Brussels-Capital and six municipalities with language facilities may choose between the Dutch and French colleges

Electoral system: Preferential list PR (no threshold) in 2 colleges, FPTP in the German-speaking college

Dutch-speaking college

N-VA (G-EFA > ?) 26.67% (+16.79%) winning 4 seats (+3)

Open Vld (ALDE) 20.4% (-0.16%) winning 3 seats (nc)

CD&V (EPP) 19.96% (-3.3%) winning 2 seats (-1)

sp.a (PES) 13.18% (-0.03%) winning 1 seat (-1)

Groen (G-EFA) 10.62% (+2.72%) winning 1 seat (nc)

Vlaams Belang (NI/EAF) 6.76% (-9.11%) winning 1 seat (-1)

PvdA+ 2.4% (+1.42%) winning 0 seats (nc)

French-speaking college

PS (PES) 29.28% (+0.19%) winning 3 seats (nc)

MR (ALDE) 27.1% (+1.05%) winning 3 seats (+1)

Ecolo (G-EFA) 11.69% (-11.19%) winning 1 seat (-1)

cdH (EPP) 11.36% (-1.98%) winning 1 seat (nc)

PP 5.98% (+5.98%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PTB-GO! 5.48% (+4.32%) winning 0 seats (nc)

FDF 3.39% (+3.39%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Debout les Belges! 2.98% (+2.98%) winning 0 seats (nc)

La Droite 1.59% (+1.59%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Others 1.14% (-6.34%) winning 0 seats (nc)

German-speaking college

CSP (EPP) 30.36% (-1.89%) winning 1 seat (nc)

Ecolo (G-EFA) 16.66% (+1.08%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PFF (ALDE) 16.05% (-4.32%) winning 0 seats (nc)

SP (PES) 15.11% (+0.48%) winning 0 seats (nc)

ProDG (EFA) 13.22% (+3.15%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Vivant 8.61% (+2.36%) winning 0 seats (nc)

The Belgian EP, federal and regional elections will be covered in a dedicated guest post.

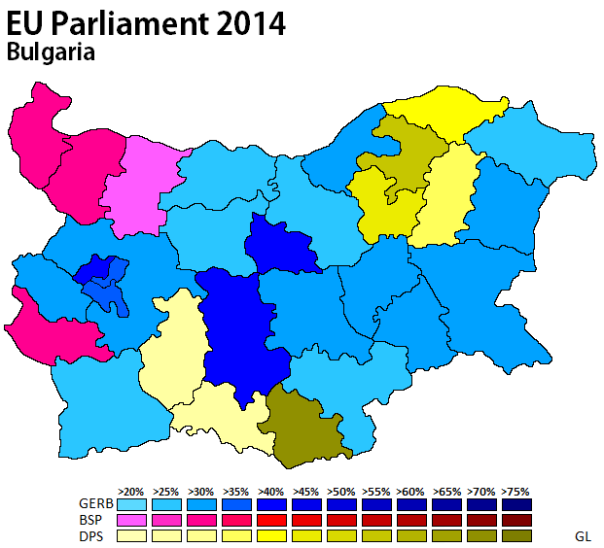

Bulgaria

Turnout: 36.15% (-1.34%)

MEPs: 17 (-1)

Electoral system: Semi-open list PR, Hare quota threshold approx 5.9% (national constituency)

GERB (EPP) 30.4% (+6.04%) winning 6 seats (+1)

Coalition for Bulgaria-BSP (PES) 18.93% (+0.43%) winning 4 seats (nc)

DPS (ALDE) 17.27% (+3.13%) winning 4 seats (+1)

Bulgaria Without Censorship 10.66% (+10.66%) winning 2 seats (+2)

Reformist Bloc (EPP) 6.45% (-1.5%) winning 1 seat (-1)

Alternative for Bulgarian Revival 4.02% (+4.02%) winning 0 seats (nc)

National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria 3.05% (+3.05%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Attack 2.96% (-9%) winning 0 seats (-2)

Others 6.26% winning 0 seats (-2)

In an election marked by low turnout – the norm for EP elections in the new member-states – the right-wing opposition party, former Prime Minister Boyko Borisov’s GERB (Citizens for the European Development of Bulgaria), ‘won’ the election and gained another two seats in the EP. The political climate in Bulgaria is incredibly bleak, and the elections in May 2013 have changed little except the colour of the head of an increasingly discredited, corrupt, incredibly disconnected and largely incompetent political elite. In 2009, only a month after the EP elections, the GERB, a new right-wing anti-corruption and ostensibly pro-European party founded by Boyko Borisov, a flamboyant and burly wrestler/bodyguard/police chief-turned-politician (he was mayor of Sofia from 2005 to 2009), won the legislative elections in a landslide, handing the governing Socialist Party (BSP) a thumping (like all Bulgarian governments up to that point, it was defeated after one term in office). Borisov quickly became unpopular, for implementing harsh austerity measures which drastically cut the budget deficit but aggravated poverty in the EU’s poorest countries (it has the lowest HDI and the lowest average wage at €333), and for proving once again that Bulgarian politicians are all hopelessly corrupt whose electoral stances are gimmicks. Borisov had previously been accused of being directly linked to organized crime and major mobsters in Bulgaria; in government, he was accused of money laundering for criminal groups by way of his wife, who owns a large bank. His interior minister wiretapped political rivals, businessmen and journalists; the top anti-crime official, who was Borisov’s former campaign manager, was suspected of having received a bribe in 1999 in return for alerting mobsters of police interventions and having turned a blind eye to drug trafficking channels in the country. Borisov’s government fell following huge and violent protests (a few protesters self-immolated) in early 2013, sparked by popular anger at exorbitant utility prices (it was said that households would soon spend 100% of their monthly income on basic necessities) charged by corrupt monopolistic private firms; but they symbolized a wider lack of trust in politicians and institutions, exasperation at political corruption, the control of politics by corrupt oligarchs and mismanagement in both the public and private sectors. Borisov engineered his own resignation in pure populist fashion and called for snap elections, in which the GERB lost 19 seats and 9% but retained a plurality of seats. However, given a polarized and dirty political climate, Borisov was unable to form government.

The opposition BSP, which increased its support by about 9%, formed a minority government in coalition with the Movement for Rights and Freedom (DPS), the party of the Turkish minority, and received conditional support from the far-right nationalist Attack party, notwithstanding the far-right’s traditional vicious anti-DPS and anti-Turkish rhetoric. Plamen Oresharski, a somewhat technocratic BSP figure (who had been a very right-wing finance minister under a past BSP government), became Prime Minister. But it was clear that the elections had changed little and that the new government was unfit to address the real challenges at hand: there remained a large discrepancy between the political elite and the citizenry, an ‘above’ vs. ‘below’ polarization rather than an ideological divide. The BSP is little different from the GERB; the left-wing rhetoric and orientation of the BSP is largely for show, because in power, from 2005 to 2009, the BSP government introduced a 10% flat tax (despite promising to amend it to make it progressive for some, the Oresharski government has keep it intact) and continued privatizations, while proving no less corrupt or incompetent than the right. Lo and behold, two weeks after Oresharski cobbled together his fragile government, major protests erupted in Sofia after the government nominated Delyan Peevski, a DPS MP and highly controversial and corrupt media mogul/oligarch, to head the secret service. Although officially owned by his mother, Peevski’s media group controls several high-circulation newspapers, TV channels and news websites which tend to be invariably pro-government while he is closely tied to Tsvetan Vassilev, the boss of a powerful bank which dispenses much of the investment for state-owned companies. Peevski is also a politician, having served as a deputy minister under a previous BSP government before he was fired and prosecuted (but later cleared) on extortion and corruption charges. The protests forced Oresharski to quickly revoke Peevski’s appointment, but the large protests, rallying tens of thousands of mostly young and/or middle-class protesters in Sofia organized through social media, continued in June and July. In late July, protesters laid siege to Parliament after MPs had approved a new debt emission without clarifying where 40% of the funds will go. Police brutally cracked down on protesters and bused the MPs out. The protests became a catch-all movement, calling for the resignation of the government, more transparency, less corruption, an end to the rule of oligarchs, cracking down on organized crime and more broadly rescuing Bulgaria from its dismal state. In late 2013, a report by the European Commission lamented the government’s inability to reform the slow and ineffective judiciary or fight corruption.

Protests have continued, but with lower turnout, marked by student sit-ins and campus occupations in October and January. Support for the protests apparently declined somewhat, with the BSP voicing concerns that the protests were partisan and that the GERB was seeking to seize control of the movement, although it does not appear that most protesters have been co-opted. Critics have attacked the middle-class background of the protesters, the strongly anti-communist and anti-leftist rhetoric of the protesters which has enabled the BSP to rally its supporters (in counter-protesters, allegedly paid) and perhaps some thinly-veiled anti-Turkish (DPS) sentiments. There has been some ‘protest fatigue’ setting in, with calls on the protesters to lay off and allow the government, although it may fall and be forced into snap elections at a moment’s notice, to prove itself. The government assures voters that it has a reformist platform, aimed at tackling corruption and improving living conditions and social benefits. However, at other times, the BSP has preferred to play political games, lashing out and pointing figures at the GERB, which retaliated with more politicking of its own.

A new party, Bulgaria Without Censorship (BBT), was founded in January 2014, led by former TV host Nikolay Barevok. BBT, which has allied with parties on the right and left, has a populist platform with promises to lock up corrupt politicians, work for ‘capitalism with a human face’ (Barekov has expressed nostalgia for the communist regime and criticized the effects of capitalism on the country) and an operation to audit the income and property of all Bulgarian politicians over the last 20 years. Barevok doesn’t come without baggage of his own – anti-corruption activists have asked questions about Barekov’s weight and there is the matter of his alleged connections to Peevski and Tsvetan Vassilev.

The GERB won the EP elections with a solid majority over the governing Coalition for Bulgaria, in which the BSP is the only relevant party. The party won 30.4%, very similar to its 2013 result, although its vote intake of 630.8k was far less than the 1.08 million votes the GERB won in 2013. The BSP coalition won 18.9%, a terrible showing similar to the 2009 EP election, when the BSP was also an unpopular governing party (then under Prime Minister Sergei Stanishev, who was soundly defeated a month later). From 942.5k votes in 2013, the BSP fell to only 424,000 votes this year.

The DPS, the party representing the Turkish minority, did very well with 17.3% of the vote, and the DPS’ vote intake was 97% of what it had won in 2013, the best hold of any major party. The DPS performs well in low-turnout elections, such as EP elections – in 2009, the DPS had won 14.1% and, most spectacularly, came close to topping the poll in the low-turnout 2007 EP by-election, winning 20.3% in an election with 29% turnout. Turnout tends to be higher in the Turkish areas of the country, where the DPS has a renowned ability to mobilize its Turkish electorate using various legal and extra-legal means (it is often accused of ‘electoral tourism’, which leads to Turkish voters voting at home in Bulgaria before turning up to vote ‘abroad’ at consulates in Turkey; plus the vote buying and intimidation techniques used by all parties); the division of the ethnic Bulgarian vote between different parties also helps the DPS top the poll even in Turkish-minority areas. For example, in this election, the division of the vote and turnout dynamics likely explain why the DPS polled the most votes in Smolyan and Pazardzhik province (which are 91% and 84% Bulgarian respectively, but the DPS has strong support with religious Muslim Pomaks – Bulgarian Muslims, who may identify as Turks – in the western Rhodope). In Kardzhali province, which is two-thirds Turkish, the DPS won 70.2% of the vote; it also topped the poll in four provinces with a significant Turkish minority (or majority, in Razgrad province) in northern Bulgaria. Peevski was the DPS’ top candidate, but he has declined to take his seat as a MEP.

The new BBT won 10.7% of the vote. It may have benefited from the collapse of the far-right Attack (Ataka), which had received about 12% in 2009 (and 7.3% in 2013), but won only 3% of the vote this year. The far-right has likely been hurt by its support for the government – the association with the DPS doesn’t seem to bother them too much, and Attack’s leader Volen Siderov spilled lots of vitriol on the protesters. The far-right’s support had previously collapsed between 2009 and 2013, when Attack had unofficially supported Borisov’s government, before it used the anti-Borisov protests to save its parliamentary seats in 2013. The Reformist Bloc, a right-wing coalition made up of the old Union of Democratic Forces (SDS, Bulgaria’s governing party between 1991 and 1992 and 1997 to 2001), former SDS Prime Minister Ivan Kostov’s fan club (the Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria) and former EU Commissioner Meglena Kuneva’s centre-right personal vehicle (Bulgaria for Citizens Movement, which failed to get into Parliament in 2013), held one of their seats with 6.5% of the vote. Kuneva was the alliance’s top candidate.

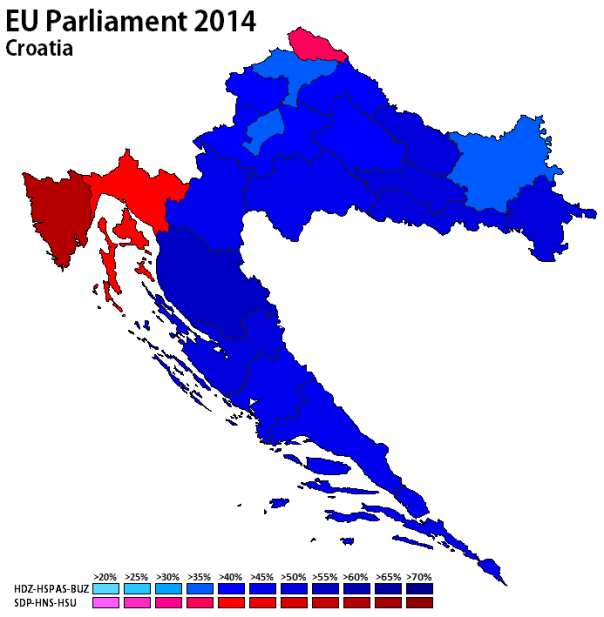

Croatia

Turnout: 25.24% (+4.5%)

MEPs: 11 (-1)

Electoral system: Semi-open list PR, 5% threshold (national constituency)

HDZ-HSS-HSP AS-BUZ (EPP/ECR) 41.42% (+8.56%) winning 6 seats (nc) [4 HDZ-EPP, 1 HSS-EPP, 1 HSP AS-ECR]

Kukuriku coalition (S&D/ALDE) 29.93% (-5.98%) winning 4 seats (-1) [3 SDP-S&D, 1 HNS LD-ALDE]

ORaH (G-EFA) 9.42% (+9.42%) winning 1 seat (+1)

Alliance for Croatia/HDSSB-HSP 6.88% (-0.07%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Labourists (GUE-NGL) 3.4% (-2.37%) winning 0 seats (-1)

Croatian Center/NF-HSLS-PGS 2.4% winning 0 seats

Others 6.55% winning 0 seats

Croatia is the EU’s newest member-state, having joined the Union on July 1 of last year – after two-thirds of voters had voted in favour of EU membership in January 2012 and three months after a by-election to elect Croatia’s 12 new MEPs (in which turnout was only 20%). Although there is no significant party which is openly anti-EU, there was little enthusiasm for joining the EU – certainly, joining the midst of the Eurozone crisis, there was none of that pomp which accompanied the EU’s Eastern enlargement in 2004. The Croatian economy has been performing poorly for nearly five years now – in fact, Croatia has been in recession for five years in a row, since the GDP plunged by nearly 7% in 2009. GDP growth is projected to remain negative in 2014, at -0.6%, although Croatia is expected to finally grow out of recession next year. Unemployment has soared from 9% when the recession began to about 17-20% today, with little relief expected in the next few years. The country’s public debt has increased from 36% to nearly 65% of the GDP. Croatia was initially hurt by the collapse of its exports to the rest of the EU with the global recession in 2009-2010, and many argue that the crisis has been so painful in Croatia because of the government’s reluctance to adopt structural reforms to reduce the country’s high tax rates, boost consumption, reducing tax revenues, downsize a large and costly public sector and restrictive monetary policies. Nevertheless, since 2009, two successive Croatian governments – from the right and left of the spectrum – have adopted similar austerity measures which have been deeply unpopular with voters and unconvincing for investors.

Between 2003 and 2011, Croatia was ruled by a centre-right coalition led by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), Franjo Tuđman’s old authoritarian-nationalist party which had transformed into a pro-European conservative party under Prime Minister Ivo Sanader (2003-2009). The HDZ government became deeply unpopular because of the economic crisis, austerity policies and corruption scandals which have landed Sanader in jail. Hit by the recession, the HDZ government under well-meaning but largely ineffective Prime Minister Jadranska Kosor introduced a new income ‘crisis’ tax and increased the VAT by 1%. More importantly, the HDZ soon became embroiled in a series of particularly egregious corruption cases involving Sanader himself. In December 2010, as the Parliament was about to strip him of his parliamentary immunity, Sanader tried to flee to Austria but was arrested on an Interpol warrant and later extradited to Croatia to face trial. In this context, an opposition coalition, Kukuriku, led by Zoran Milanović’s Social Democrats (SDP) in alliance with the left-liberal Croatian People’s Party-Liberal Democrats (HNS-LD) and the Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS), won the December 2011 elections in a landslide with 40.7% against only 23.9% for the HDZ coalition.

In office, Milanović’s government has continued with similar austerity policies, which the centre-left government claims are tough measures necessary to make Croatia competitive in the EU and which any government would be forced to take. He has cut public spending, begun a wave of privatizations, reformed pensions, liberalized foreign investment and has talked of cutting 15,000 jobs from the public sector. Some of his controversial economic policies have been opposed by trade unions and employees, while the likes of The Economist dislike the government’s reluctance to cut taxes and public sector wages. The SDP-led government is widely viewed as being uninspiring, and some of Milanović’s decisions have baffled supporters – for example, Milanović barred (until January 2014) the extradition to Germany of former Yugoslav-era secret police chief Josip Perković, who is wanted for the murder of a Croatian defector in Germany in 1983. The opposition HDZ is hardly in better shape. Tomislav Karamarko, the HDZ leader since 2012, has not really improved the HDZ’s standing in opinion polls. In late 2012, the opposition leader was accused of creating a fake scandal to discredit the government (a right-wing paper had alleged that the interior minister had been tapping phones of intelligence operatives, before a left-wing paper countered by claiming that the intelligence operatives had suspected ties with the mafia). In December 2012, Ivo Sanader was found guilty in a first corruption trial and sentenced to 10 years in jail, for having accepted bribes from Austria’s Hypo Bank and an Hungarian oil company. In March 2014, Sanader received another 9 year prison sentence when he – and the HDZ – were found guilty of corruption, accusing Sanader of being behind a scheme to siphon off funds from state-run institutions for personal and partisan financial gain. There has, however, been a mobilization of socially conservative and nationalist opinion, buoyed by the successful initiative referendum last year which amended the constitution to ban gay marriage. The ban on same-sex marriage was approved by 65.9% of voters, despite the opposition of the Prime Minister.

The opposition coalition, made of the HDZ, the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS), the national-conservative Croatian Party of Rights dr. Ante Starčević (HSP-AS) and a pensioners party, won a strong victory – but with only a quarter of the electorate actually turning up. With 41% of the vote, the HDZ’s result is about 8.6 points better than what it had won in the by-election last year, when the right had defeated the SDP coalition by a small margin. The right-wing coalition won 381,844 votes, which is less than what the right received in the 2011 parliamentary elections (554,765), when it had won only 23.4%. Given the low turnout, it is likely a matter of differential mobilization – with opposition voters being more motivated to turn out than supporters of an unpopular and uninspiring government. Polls for the next general elections have showed the right to be tied with or leading the government, but more because the government’s numbers have collapsed to a low level than any major increase in the right’s support (which stands at 24-27%, with the gains from the HDZ’s result in 2011 coming from the addition of the party’s new allies, the HSS and HSP-AS). Turnout was slightly higher in some of the HDZ’s traditional strongholds in Dalmatia, but correlation between turnout and the right’s support was not apparent at the county level. As in 2013, the top vote-winning candidate on preferential votes was Ruža Tomašić, the MEP from the nationalist HSP-AS, who sits with the British Tories in the ECR group (the HDZ, and now the HSS, which won one of the coalition’s six MEPs, sits with the EPP). She won 107,206 votes, or 28.1% of votes cast for the list.

The SDP-led coalition expanded compared to the 2013 EP election, taking in the Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS), which had won 3.8% of the vote (and topped the poll in Istria, a traditional left-wing bastion), but despite this expansion, the Kukuriku list won 6% less than the SDP-IDS’ combined total from the 2013 by-election and the 275.9k votes it won represents a huge collapse from the 958,000 votes the left had won in 2011. Tonino Picula, an incumbent SDP MEP, received the most preferential votes (48.1%), while the Kukuriku coalition’s top candidate on the list, EU Commissioner Neven Mimica won only 8.1% of preferential votes cast for the list.

To a large extent, the other major winners of the election were smaller parties, although only one of them won seats. ORaH – Croatian Sustainable Development (although orah means nut or walnut in Croatian)- is a new green party founded by former SDP environment minister Mirela Holy, who resigned from cabinet in 2012 citing disagreements with the government’s policy. ORaH describes itself as a socially liberal, progressive green party of the centre-left, and is seeking association with the European Greens. The party’s support has soared in polls since its creation in October 2013, now averaging about 9-11% nationally. Likely pulling votes from the left – ORaH performed best in traditionally left-leaning counties such as the city and county of Zagreb, Istria and Primorje-Gorski Kotar – the party won 9.4% or 86.8 thousand votes, electing Mirela Holy to the EP.

On the right of the spectrum, the Alliance for Croatia, a new right-wing coalition made of the regionalist/conservative Croatian Democratic Alliance of Slavonia and Baranja (HDSSB), the far-right Croatian Party of Rights (HSP) and the new far-right Hrast movement, won 6.9% of the vote, but failed to win a seat. To a large extent, the alliance’s support remained concentrated in the HDSSB’s traditional stronghold in Osijek-Baranja county, where it won 16.4%, but it did win some significant support outside the poor conservative region of Slavonia, notably in Zagreb (7%) and Split-Dalmatia county (10.9%).

The Labourists, a left-wing anti-austerity party founded by HNS dissident Dragutin Lesar, which won 5% in 2011 and 5.8% in 2013, lost its only MEP. The party, which polled up to 10% in 2012, has seen its support declined to 7-8%. The Partnership of the Croatian Centre, a new centre-right alliance including ophthalmologist Nikica Gabrić’ National Forum, the centre-right Social Liberals (HSLS) and two small local parties, won 2.4% of the vote. Former Prime Minister Jadranka Kosor, expelled from the HDZ in March 2013, was the alliance’s top preferential vote-winner, with 29.7% of the votes cast for the alliance in her name against 24.2% for Gabrić.

This EP election should probably not be taken as an accurate depiction of voters’ view, because turnout was just so low. Polls suggest that the next election, due by 2016, will result in an exploded political scene, with both the SDP and HDZ-led blocs polling below 30% with third parties such as ORaH, the Labourists, the HDSSB and the centrist alliance being all potential kingmakers in what may be a very divided Sabor.

Cyprus

Turnout: 43.97% (-15.43%) – mandatory voting unenforced

MEPs: 6 (nc)

Electoral system: Preferential list PR, 1.8% threshold (national constituency)

DISY (EPP) 37.75% (+1.76%) winning 2 seats (nc)

AKEL (GUE-NGL) 26.98% (-8.37%) winning 2 seats (nc)

DIKO (S&D) 10.83% (-1.48%) winning 1 seat (nc)

EDEK-Green (S&D) 7.68% (-3.76%) winning 1 seat (nc)

Citizen’s Alliance 6.78% winning 0 seats (nc)

Message of Hope 3.83% winning 0 seats (nc)

ELAM 2.69% (+2.48%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Others 2.42% winning 0 seats (nc)

Cyprus has been especially hard hit by the financial crisis. Cyprus’ huge offshore banking sector speculated on the Greek debt, and came under pressure beginning in 2008-2009 as bad debt ratios rose and they incurred major loses when Greece restructured its debt. The country’s economy collapsed after 2011: in 2013, the worst year of the crisis, the Cypriot GDP shrank by 6% and is projected to remain in recession in 2014 (-4.8%); the public debt has increased from 58.5% in 2009 to 121.5% in 2014, one of the highest public debts in the EU; unemployment has jumped from 5% in 2009 to 19% in 2014, the third highest in the EU. The Cypriot crisis was particularly complicated for EU policymakers and the IMF because the issue was the island’s gigantic and overextended banking sector – in 2011, its banking sector was said to be eight time as big as its GDP. To complicate matters further, a lot of banking deposits were held by wealthy Russians and Russians make up an important share of the local population.

Cyprus had been in trouble for quite some time before 2013, but the government of President Dimitris Christofias, from the communist Progressive Party of the Working People (AKEL), in office since 2008, initially resisted pressure to seek a bailout from the troika, downplayed the severity of the crisis and opposed implementing austerity and structural reforms. Christofias and the troika didn’t like one another; the latter didn’t trust him to implement structural reforms such as reductions in social spending and public sector wages (which is said to be overstaffed and generously paid compared to the private sector). As the crisis worsened and Cyprus’ credit rating was downgraded, the island was forced to ask for a European bailout in June 2012. Cyprus needed a €17 billion loan spread out over four years, a substantial sum of money representing one year’s worth of the Cypriot GDP; over half of that was needed to recapitalize its banks. In 2011, Cyprus also received a €2.5 billion loan from Russia, which is influential in Cyprus. President Christofias, however, balked at the terms of such deals: he opposed privatization of state assets and was a vocal critic of austerity policies. That being said, his government started introducing austerity policies in 2012 and early 2013: cuts in social spending, a VAT hike and the introduction of retirement contributions for civil servants. With a poor economic record, Christofias did not run for reelection to the presidency in February 2013, and the election was won in a landslide by Nicos Anastasiades, the leader of the conservative pro-EU, pro-bailout and pro-reunification Democratic Rally (DISY). With a more friendly and credible partner, the troika began negotiations for a bailout.

The first bailout agreement in March 2013 represented a major new step in the Eurozone crisis: it imposed a one-time levy on insured and uninsured bank deposits, at a 6.7% rate for deposits up to €100,000 and 9.9% on deposits above that rate. Designed to prevent the island’s banking sector from completely collapsing (but also because Germany didn’t want to loan the full €17 billion and only agreed to €10 billion), the ‘haircut’ on deposits was extremely unpopular and provoked a firestorm in Cyprus and across the EU. A few days later, with pressure from Russia (which was severely irked by the bailout terms) and local protesters, the Parliament rejected the deal. There were worries that Cyprus might be forced to pull out of the eurozone following a tense standoff with the ECB, but a second deal was reached: the Laiki Bank, the second largest bank, would be restructured in a bad bank, spared all insured deposits of €100,000 and less but levied uninsured deposits at the Laiki Bank and 40% of uninsured deposits in the Bank of Cyprus. In the final agreement, no bank levy was imposed, as the Laiki Bank would be directly closed, although uninsured deposits over €100,000 at the Laiki Bank would be lost and those over the same amount at the Bank of Cyprus would be frozen for a haircut if necessary. The Cypriot government also accepted implementation of an anti-money laundering framework, reducing the deficit, structural reforms and privatization. Cyprus also imposed capital controls. However, the first botched bailout was not forgotten in collective memories across Europe, with many fearing that there was now a precedent for ‘bail-ins’ and haircuts in the EU. It also soured Cypriots’ opinion of the EU, fueled by the view that they were the victims of the crisis and were unfairly blamed and punished for it.

With its business model destroyed, the country fell into a deep and painful recession, although the intensity of the recession did not turn out as bad as was predicted last spring and tourism didn’t perform nearly as bad as expected due to Russian tourists. In February 2014, the anti-reunification Democratic Rally (DIKO)’s cabinet ministers resigned and the Parliament did not pass a privatization program, which controversially privatized electricity, telecommunications and ports. A few days later, however, Parliament adopted a revised privatization program, which aims to raise €1.4 billion to pay back the next €156 million aid tranche. International creditors had threatened to withhold payments. The other part of the story behind DIKO’s resignation was its opposition to the reopening of talks with the Turkish Cypriot-controlled north (the TRNC); the issue has been at an impasse since Greek Cypriots in the south rejected the 2004 Annan Plan to reunify the island in a referendum right before it joined the EU, but Anastasiades and DISY were the only leading southern politicians to call for a yes vote in 2004 (Christofias and AKEL are pro-reunification, but Christofias had crucially failed to endorse the yes at the last moment).

The EP election saw extremely low turnout, by Cypriot standards. In 2004, turnout was 72.5%, but it fell to a low of 59.4% in 2009. For comparison, in the 2013 presidential election, over 80% of the electorate had turned out. This year, turnout collapsed below 50%, to 44% – an all-time low. The cause of the low turnout is likely political dissatisfaction and growing apathy – Cyprus hasn’t seen major social movements or protests against the austerity policies imposed, unlike Greece or Spain. As predicted by local pollsters, in a low turnout election, most voters were party loyalists who voted along the traditional party lines. The governing DISY won the election; Anastasiades has managed to shrug off the humiliation of March 2013. However, despite a strong victory, its actual number of voters – because of the low turnout – falls far short of what DISY won in 2009 or 2013. The major loser was the communist AKEL, the former ruling party, which suffered from the demobilization of its electorate, traditionally loyal, after the disastrous record of AKEL’s last term in government. AKEL’s anti-credibility also lacks in credibility. Cyprus stands out from the rest of Europe – and the world – for the strength of the communist movement on the island, which has been active since the 1920s and present in Parliament since independence. AKEL generally tended to support Archbishop Makarios’ government and oppose the enosist (union with Greece) far-right before 1974. DISY was founded as the most pro-Western and pro-NATO centre-right party in 1976 after the invasion, by Glafkos Clerides.

The two smaller parties, the anti-reunification DIKO and the social democratic EDEK (founded by Makarios’ physician and Greek nationalist Vassos Lyssarides in 1969; it ran in alliance with the Greens, KOP) lost votes. Smaller parties benefited from the political climate, but failed to win seats. The Citizen’s Alliance, an anti-corruption, Eurosceptic and anti-Turkish party, won 6.8% of the vote. Somewhat notable was the small success of ELAM (National Popular Front), a far-right/neo-Nazi party tied to Greece’s Golden Dawn (XA). It won 2.7%, a ‘major’ gain from 2009. With over 6,900 votes, ELAM actually won more votes than it did in 2013.

DISY won all districts. It won its biggest victory in the small Greek Cypriot portion of Ammochostos/Famagusta district, with 47.9%, but only 14,000 or so votes were cast. AKEL was defeated in Larnaca district, the traditional communist bastion on the island, with 33.7% to DISY’s 39.2%. In Pafos district, EDEK suffered major loses, losing 8% of the vote.

Czech Republic

Turnout: 18.20% (-15.43%)

MEPs: 21 (-1)

Electoral system: Semi-open list PR, 5% threshold (national constituency)

ANO 2011 (ALDE) 16.13% (+16.13%) winning 4 seats (+4)

TOP 09-STAN (EPP) 15.95% (+15.95%) winning 4 seats (+4)

ČSSD (S&D) 14.17% (-8.21%) winning 4 seats (-3)

KSČM (GUE-NGL) 10.98% (-3.2%) winning 3 seats (-1)

KDU-ČSL (EPP) 9.95% (+2.31%) winning 3 seats (+1)

ODS (ECR) 7.67% (-23.78%) winning 2 seats (-7)

Svobodní (EFD) 5.24% (+3.98%) winning 1 seat (+1)

Pirate Party 4.78% (+4.78%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Green Party (G-EFA) 3.77% (+1.71%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Úsvit 3.12% (+3.12%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Others 8.24% (-12.79%) winning 0 seats (nc)

In the past five years, there have been huge changes in Czech politics, which may portend a realignment of the country’s partisan and political system, which is more unstable and exploded than ever before. For years, Czech politics were dominated by the centre-right and Eurosceptic Civic Democrats (ODS), close allies of the British Tories; and the centre-left Social Democrats (ČSSD); ideological differences became muted after the two rivals signed an ‘opposition agreement’ in 1998 in which the ODS agreed to tolerate a ČSSD minority government in return for government jobs and keeping access to the spoils. The 1998 agreement was immediately unpopular, and briefly boosted the prospects of the largely unreformed Communist Party (KSČM) and the centrists, led by the Christian Democrats (KDU-ČSL). It is cited to this day as the moment at which the ODS and ČSSD agreed to share the spoils, betray the voters and allowed politics to become corrupted by a murky group of lobbyists and businessmen. Yet, the system did not collapsed: after both parties did poorly in 2002, they both gained votes after a very polarized and acrimonious closely-fought election in 2006. The ODS formed an unstable government reliant on the KDU-ČSL and the Greens, which fell in early 2009. The 2010 elections were the first sign of major cracks in the system: both the ODS and ČSSD, while still placing on top, won only 20% and 22% respectively, a major fall from 2006. Two new centre-right parties, the pro-European conservative TOP 09 and the ‘anti-corruption’ scam Public Affairs (VV), did very well, and entered government with the ODS, led by Petr Nečas.

Petr Nečas’ government agenda included fiscal responsibility, the fight against corruption and rule of law. It basically failed on all three counts, especially the last two. Rigid austerity policies – one-point increases in the VAT rates, a new higher tax on high incomes breaking the flat tax (introduced by a previous ODS cabinet), and allowed pensions savings to be diverted into a private fund – were unpopular, and some faced hostility from the right (President Václav Klaus, a controversial and brash Eurosceptic, opposed the VAT hike and disliked the pension reform). The Czech Republic suffered a double-dip recession, and is projected to start growing again – but slowly – only this year. The government turned out to be awash with corrupt politicians – it was revealed that VV was actually part of a business plan for a security company owned by the party’s unofficial leader and cabinet minister Vit Bárta, who also bribed VV MPs in return for their loyalty. VV split and rapidly collapsed. In June 2013, Nečas’ chief of staff and mistress (the two have since married), was arrested along with military intelligence officials and ODS MPs; she was accused of asking military intelligence to spy on three civilians, including Prime Minister Petr Nečas’ then-wife; and brokering a bribery deal to convince three rebel ODS MPs to resign to save the government on the VAT hike vote in 2012. Nečas, who had been known as ‘Mr. Clean’, was forced to resign and the ODS’ support, which had already collapsed to only 12% in the 2012 regional elections, fell in the single digits. President Miloš Zeman, a brash and sharp-elbowed former ČSSD Prime Minister (who later left the party), who won the first direct presidential election in early 2013, controversially appointed a cabinet of friends and allies which did not receive the confidence of the Chamber and forced snap elections in October 2013.

The October 2013 elections saw major political changes. The ČSSD, torn apart by a feud between the anti-Zeman leadership (Bohuslav Sobotka) and a pro-Zeman rebel group (Michal Hašek) and weakened by corruption of its own, once again sabotaged its own campaign and won an all-time low of 20.5% – although they still placed first. The ODS, worn down by corruption and the economy, collapsed to fifth place with 7.7%. TOP 09, a pro-European party which otherwise shares much of the ODS’ low-tax, small government and pro-business agenda, surpassed the ODS, taking 12%, although it lost 4.7% of its vote from the 2010 election. TOP 09’s unofficial leader and popular mascot is Karel Schwarzenberg, the colourful and popular prince and former foreign minister; the party’s actual boss is the far less glamorous Miroslav Kalousek, a somewhat slimy politico who came from the KDU-ČSL. The KSČM placed third with 14.9%, a strong result but not the party’s best; the KSČM has a strong and loyal core of support and it has always done well when the ČSSD is unpopular or discredited (in 2002 and 2004, for example, or in 2012), but the party, despite some evolution, remains a controversial pariah which has not officially supported or participated in a national government (but governs regionally with the ČSSD). The sensation, however, came from ANO 2011 – a new populist party founded and led by Andrej Babiš, a billionaire businessman (owner of Agrofert, a large agricultural, agrifood and chemical company in the country) of Slovak origin. Babiš campaigned on an attractive anti-system, anti-corruption, anti-politician and pro-business centre-right platform which denounced professional politicians, corruption, government interference in the economy and promised low taxes. But Babiš is a controversial man – during the campaign, Slovak documents alleged that he was a collaborator and agent of the communist regime’s secret police; Babiš has been compared to Silvio Berlusconi, and raised eyebrows when he bought the country’s largest media group before the elections. ANO 2011 placed second with 18.7%. Úsvit (Dawn of Direct Democracy), another new right-wing populist party founded by eccentric and idiosyncratic Czech-Japanese businessman and senator Tomio Okamura, won 6.9%. Described by opponents as ‘proto-fascist’, Úsvit, which called for direct democracy and a right-wing economic/fiscal agenda (low taxes, attacking people ‘a layer of people who do not like to work’), controversially called on ‘gypsies’ to be sent back to India. Úsvit’s anti-corruption outrage rings hollow, because one of its candidates (who lost) was Vit Bárta.

Government formation was complicated by tensions between the ČSSD and ANO, which had not had kind words for one another; and tensions within the ČSSD, where Hašek’s supporters, likely with Zeman’s underhanded support, unwisely and unsuccessfully tried to topple Sobotka. Despite Zeman’s obvious misgivings about Sobotka and his desire to continue influencing the government, in January 2014, he agreed to appoint Sobotka as Prime Minister at the helm of a coalition government with the ČSSD, ANO and KDU-ČSL. Notwithstanding some very real policy differences and partisan tensions between the two main partners, the coalition has agreed to a moderate platform, which aims to keep the budget deficit below the EU’s 3% limit, eliminate healthcare user fees, raise pension payments and the minimum wage, lowering the VAT on some products, rolling back the ODS’ pension reforms, tax breaks for families with children and may lower compensation payments to churches (the ODS government controversially signed a deal to return real estate valued at 75 billion CZK to churches and offer financial compensation of 59 billion CZK). It will also take a more pro-EU direction than the ODS, having pledged to ratify the European Fiscal Compact. ANO sends mixed messages on Europe, trying to be both pro-EU and sufficiently Eurosceptic at the same time. Babiš is finance minister in the new government, and his continued ownership of Agrofert has led to accusations of conflict of interest.

The EP election saw extremely low turnout, down from 28.3% in 2004 and 28.2% in 2009 (which was already low, even for low-stakes elections in the country), reaching only 18.2% of the vote. With a fairly popular government still in honeymoon with little controversies yet, there was likely even less motivation to vote this year. As in the last two EP elections, it appears that the electorate which turns out is to the right of the average voter: compared to national polling, the ČSSD and KSČM did slightly worse (they’re currently polling 19-21% and 14-17% respectively) while TOP 09, polling 8-11%, did quite well. ANO, which is polling very well nationally (20-28%), did not do as well; while it pulls mostly from voters who had backed the right in 2010, it is a more rural and regional base lacking the Czech right’s traditional well-off urban component. Turnout figures regionally confirm pro-right differential turnout, with the highest turnout being recorded in Prague, the right’s (TOP 09) stronghold, at 25.8%, while turnout was below 20% in every other region and very low (15%) in Moravia-Silesia, the Social Democrats’ strongest region (and 13% in Karviná district, a coal mining area where the party had won 32% in 2013). In Prague, TOP 09 received 27% against 14.5% for ANO.

ANO topped the poll with 16.1%, just ahead of TOP 09, which won 16%. The left – ČSSD and KSČM – did poorly because of low leftist turnout, winning only 14.2% and 11% respectively, in both cases this represents a substantial loss from the last EP election in 2009 (where the ČSSD had done poorly as well). The KDU-ČSL did well, winning nearly 10% of the vote and topped the poll in Vysočina, South Moravia and Zlín regions, dominating their traditional rural clerical Moravian strongholds. A small anti-EU party, Svobodní (Party of Free Citizens) won 5.2% and one seat; the party, which is close to UKIP and whose new MEP (and leader) is a former adviser to Klaus, supports a small government, low taxes and abolishing subsidies and income taxes. The party is anti-EU, wishing to transform it into a voluntary free trade association or to leave the EU to join the EFTA; it opposed Lisbon and the euro, and now opposes the European Fiscal Compact. Having won less votes than in 2013 (when it won 2.5%), the party likely owes its entrance into the EP to the higher turnout in Prague, where it won over 7% of the vote.

The map on the left shows the results by municipality. TOP 09 clearly dominated Prague, Brno and Plzeň; ANO was strongest, like in 2013, in right-leaning areas of Bohemia, outside the urban centres in towns and rural areas (and in places where Agrofert is a major employer); the ČSSD managed to top the poll in industrial Silesia but few other places; the KSČM was strongest in North Bohemia and other former Sudeten German territory (which was re-settled by Czechs post-1945); the KDU-ČSL dominated rural Moravia.

Ihned’s ever-useful data blog has a tool (in Czech, but Google Translate does fine) allowing you to see average results in towns based on certain sociodemographic filters. It confirms the link between turnout and stronger support for TOP 09: where turnout was above the national average, TOP 09’s vote share was 6.9% above its national average; the ODS, Svobodní, the Pirates and the Greens also performed better where turnout was higher, while ČSSD and KSČM clearly did poorer where turnout was higher. ANO did slightly better in areas with lower turnout. The other demographic filters give a good portrait of the voter base of each party. Unsurprisingly, the strongest correlation is between KDU-ČSL and religiosity in this very atheist country – in areas where the share of the faithful is above the national average (which appears to be 14%), the Christian Democrats placed first with 18.1%. The party’s support rise exponentially as the share of the faithful increase in any given area, taking 30% where it is above 28%, 36% where it is over 40% and 43.2% in the few municipalities where more than half of the population are religious. TOP 09’s traditional supporter was very urban, young, not married, very well educated (post-secondary), employed, living in a house and probably an entrepreneur or self-employed. The ČSSD and KSČM had a slightly older, less urban, less educated (especially the Communists) electorate which was also more likely to be unemployed (especially for the KSČM) and far more likely to be an employee. ANO’s support was fairly composite; with no clear core voter base: the party’s average voter is slightly more likely to be an entrepreneur or self-employed, a bit less likely to be unemployed but otherwise its support is less clear-cut than that of TOP 09, ODS and even Svobodní (the right-wing parties). Like in 2013, ANO likely attracted a very demographically and ideologically varied electorate.

Denmark

Turnout: 56.32% (-1.38%)

MEPs: 13 (nc)

Electoral system: Preferential list PR (national constituency), seats distributed to alliances (separate lists with votes being pooled together) and then to independent lists (de jure 2% threshold)

O (DF) – Danish People’s Party (EFD > ECR) 26.61% (+11.33%) winning 4 seats (+2)

A (SD) – Social Democrats (S&D) 19.12% (-2.37%) winning 3 seats (-1)

V – Venstre (ALDE) 16.68% (-3.56%) winning 2 seats (-1)

F (SF) – Socialist People’s Party (G-EFA) 10.95% (-4.92%) winning 1 seat (-1)

C – Conservative People’s Party (EPP) 9.15% (-3.54%) winning 1 seat (nc)

N – People’s Movement against the EU (GUE-NGL) 8.07% (+0.87%) winning 1 seat (nc)

B (RV) – Social Liberals (ALDE) 6.54% (+2.27%) winning 1 seat (+1)

I – Liberal Alliance 2.88% (+2.29%) winning 0 seats (nc)

The right-wing populist/far-right Danish People’s Party (DF, or by its ballot paper abbreviation, O) won a remarkable victory – its biggest electoral success, both in terms of percentage and number of votes – in the party’s history, confirming that the party, on the upswing since the 2011 legislative election, is stronger than ever before and is now in a position to compete with the traditional parties of the left (Social Democrats, A) and right (Venstre/Liberals, V) for power.

The left bloc – led by the Social Democrats and made of the green/left-wing Socialist People’s Party (SF), the left-liberal Social Liberals (RV) with external support from the far-left Red-Green Alliance (Enhedslisten, Ø) – very narrowly won the 2011 elections, ending ten years of right bloc rule – by the centre-right Liberals (V) and Conservatives (C) with external support from the DF. It was already a somewhat Pyrrhic victory, because the SDs, led by Helle Thorning-Schmidt, saw their support decline even further (to an historic low of 24.8%) while only RV – which gained 8 seats, to take 17 seats and Ø – which won an historic 6.7% ans 12 seats made gains (SF, which won an historic 13% in 2007, fell to 9%). The left’s victory owed mostly to the gains made its most right-wing and left-wing components, and general fatigue with a tired right-wing government. Helle Thorning-Schmidt (‘Gucci Helle’), the notoriously aloof and ‘snobby’ SD leader, was already fairly unpopular in 2011. Since then, the government, and the SDs in particular, has become badly unpopular.

The government, initially made up of ministers from the SDs, SF and RV, adopted a rather right-wing economic and fiscal policy which dismayed many of the left’s voters and led to major tensions with the Red-Greens, who provided outside support to the government. Soon after taking office, the new government was compelled to accept sharp cuts in the efterløn, a scheme which lets workers retire early on a reduced pension – the policy is popular with manual works in physically demanding jobs, but unpopular with white-collar workers and academics. The outgoing right-wing government, with the backing of the Social Liberals (whose economic and fiscal policy is fairly right-leaning and supportive of lower taxes and a slightly less generous welfare state), had passed a reduction in the efterløn and an increase in the retirement age; after coming into office, the SDs and SF accepted the new policy – after the SDs had vigorously campaigned against changes to the efterløn in the 2011 election. In June 2012, the government agreed to a tax reforms with the Liberals and Conservatives, which increased the top tax threshold (thus reducing taxes on the wealthy) and employment allowance (reducing the taxes on wages) and reduced state benefits (unemployment insurance, early retirement, child benefits); with the aim of increasing labour output, enticing Danes to work more and increasing the the economic benefit of working relative to receiving welfare. The government argued that it was taking difficult but necessary long-term measures to address demographic challenges to Denmark’s aging workforce, but the very neoliberal flavour of the tax reform infuriated the Red-Greens and threw SF, already criticized for having moved to the right to increase the party’s ‘respectability’, in a difficult position. Relations between the government and the Red-Greens were severely damaged; while an increasingly large number of SF voters (and some SD voters) defected to Ø, a process which actually begun in the 2011 election, when SF had lost a share of its most left-wing 2007 voters to Ø. At the same time, the right bloc took a decisive lead in polls; the SDs lost a number of working-class supporters to the DF and V, likely the result of voters disgruntled by the government’s shift on efterløn, a slight liberalization of tough immigration policies (under DF pressure, the previous VC government had adopted some of the EU’s strictest immigration laws, including the 24-year-rule, which imposes strict conditions on family reunification and spouses’ immigration; the left has largely kept these popular rules in place, while liberalizing the more contentious aspects, such as the heavily reduced social benefits for immigrants and detention centres for asylum seekers being processed), the mediocre economic situation, government scandals and mishaps and broken promises.

In September 2012, SF leader Villy Søvndal, who had led the party’s shift towards the centre and ‘respectability’ between 2007 and 2011 and supported close collaboration with the SDs in government, stepped down. In a high-stakes leadership race, Annette Vilhelmsen, a SF MP positioned on the party’s left, defeated health minister Astrid Krag, the candidate of the party’s ‘right’. Although Vilhelmsen dumped Thor Möger Pedersen, the young and unpopular (with the SF’s left) taxation minister and shifted rhetoric to the left, her election did not signal a major shift in the SF’s behaviour in government – it still played second-fiddle to the stronger SDs – nor did it turn around the SF’s sinking polling numbers (in 2013, SF’s numbers sank further, in the 3-5% range, while Ø polled up to 10-14%). The government – especially SD and SF – continued to be badly unpopular in 2013, with the right retaining a decisive lead (about 55-45 for the right bloc in total). A social assistance reform (which reduced benefits for young people and added more stringent eligibility rules; it was approved in August 2013 with the support of all four right-wing parties and the opposition of Ø) and the continued mediocrity of the economy (weak growth in 2013, unemployment at 7%) meant that the Social Democrats saw their support collapse even further, falling to 15-18% in early 2013 before edging back over 20% later in the year. V, which was still polling over 30%, DF and Ø all took their shares of SD voters. SF voters from 2011 divided between loyalty, moving to the left (Ø) or doing like some party members and parliamentarians did (move to the SDs).

In November 2013, the government passed its budget with support from V and C, after failing to bridge differences with Ø. The budget included millions in concessions to businesses and for higher job allowances. Although unpopular on the left, its effect was mitigated by V’s troubles, after the party’s leader and former Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen was accused of spending over a million kroner on luxury flights and hotels in his capacity as chairman of the Global Green Growth Initiative – which is publicly funded by the Danish government. However, development minister Christian Friis Bach (RV) was forced to resign as well, after it turned out that he had lied about the government not approving the expensive travel rules).

In late January 2014, the government ran into yet another crisis with a deal to sell 19% of DONG Energy – Denmark’s largest energy company (of which the government owned 81%) – to the American investment bank Goldman Sachs. The deal attracted criticism from the left and DF because of Goldman Sachs’ role in the financial crisis and their plan to buy the shares via tax havens to pay less taxes in Denmark. The issue reopened the question of SF’s participation in government, and led to internal chaos in the party: the SF executive narrowly voted to accept the sale, some opponents of the deal in SF resigned, Ø pushed a parliamentary motion to postpone the sell to force SF MPs to take a stance and finally it culminated with SF leader Vilhelmsen announcing her resignation and that SF was leaving the government (but would continue to support it). Thorning-Schmidt shuffled her cabinet, creating a new government with the SDs and RV. SF voted in favour of the sale in committee, honouring the executive committee’s decision. Supporters of the government within SF ranks – largely supporters of former SF leader Villy Søvndal from the pro-SD ‘workerite’ right of SF – defected to the SDs, including defeated leadership contender Astrid Krag (who nevertheless lost her health portfolio) and former Communist stalwart Ole Sohn. Pia Olsen Dyhr, a member of SF’s ‘green right-wing’, was acclaimed as SF’s new leader.

A month after this crisis, the government ran into another hot potato which stoked Eurosceptic sentiments ahead of the EP election. The old right-wing government tried to limit EU nationals’ ability to receive child benefits by requiring that they have lived or worked in Denmark for two of the last ten years. In 2013, the EU Commission notified Copenhagen that this was not in accordance with EU law (as it discriminated against other EU nationals), and the Danish government began administering according to EU law, which takes precedence, and in February 2014 it proposed a law to amend Danish legislation to make it consistent with EU law. The opposition (V, C, DF, Liberal Alliance) and Ø (which denounced ‘bowing down’ to the EU and called on the government to follow Danish law) supported a motion reaffirming the Danish law. To mitigate the boost which DF received, at the expense of both V (which had some reticence about taking such a tough anti-EU stance) and the SDs, the government proposed tougher controls of EU citizens’ access to welfare benefits. In early May, the government was voted down on the motion on child benefits – with the opposition parties, including the Liberals, and the Red-Greens voting in favour of the motion and the government and SF voting against. In practice, the government will keep administering the law according to EU directives.

In this context, DF won a crushing victory. The party received 26.6% of the vote, by far the party’s highest vote share ever (the previous record, set five years ago, was 15.3%); but it also received the highest raw vote in its history – 605,889 votes, easily surpassing the previous record, which was 479.5k votes in the 2007 legislative election. DF benefited from national dynamics in its favour, but also a personality factor. Nationally, DF has been on an upswing since it lost votes and seats for the first time in its history in the 2011 election. Cashing in on the feeling of betrayal by the left of working-class voters, DF has made inroads with workers and SD voters: according to a study in February, 12% of SD voters from the last election would now vote for DF, along with an estimated 9% of SF and V voters from 2011. In the last weeks drawing up to the EP election, DF additionally benefited from two events: firstly, the political debate on child benefits for EU nationals and the application of EU law over the Danish law and secondly, a new scandal about V leader Lars Løkke Rasmussen using his party’s purse to pay for his clothes and a family vacation down south. In both cases, these events reflected badly on the Liberals, whose support in national polling has declined significantly as a result. In the first case, the child benefits debate increased latent Eurosceptic feelings and allowed DF to attract V supporters for the EP elections. In the second case, V was the target of attacks from the media and the right-wing partners (C, DF, Liberal Alliance). Secondly, DF had the strongest top candidate of all parties in this open-list election. Incumbent DF MEP Morten Messerschmidt is quite popular and he’s the most well-known MEP: already in 2009 he had broken the Danish record for most personal preferential votes in an EP election (set by former SD PM Poul Nyrup Rasmussen in 2004). This year, he broke his own record for most preferential votes in an EP election in Denmark, winning 465,758 preferential votes or 20.5% of all votes cast. His closest competitor, SD MEP-elect Jeppe Kofod won only 170,739 preferential votes (7.5%).