Category Archives: Alberta

Prince Edward Island and Alberta (Canada) 2015

Provincial elections were held in the Canadian provinces of Prince Edward Island (PEI) and Alberta on May 4 and 5, 2015 respectively.

Prince Edward Island

All 27 members of the Legislative Assembly of Prince Edward Island, the unicameral provincial legislature of the province, were up for reelection. The smallest province by population, PEI also has the smallest provincial legislature in Canada. As in every other province, members – styled MLAs – are elected by FPTP in single-member constituencies (which are called districts in PEI). However, PEI was the last Canadian jurisdiction to transition to only single-member constituencies – until the 1996 election, PEI’s MLAs were elected in two-member districts, with each of the island’s three counties electing 10 members in 5 two-member districts (until 1966, when 5th Queens was divided to create a 6th Queens district covering part of Charlottetown, the provincial capital). Since PEI did not abolish its old upper house but instead merged it with its lower house in 1893, the two-member districts returned one assemblyman and one councillor. Until 1963, while all voters could vote for assemblymen, only property owners could elect the councillor. Although the property qualification was dropped in 1963, the nominal titles continued to be used until the creation of the single-member districts.

The two-member districts map, which had remained unchanged save for one exception for a hundred years, and contained very large differences in population across districts, was struck down in Mackinnon v. Prince Edward Island in 1993. The successor map was challenged on the grounds that it over-represented rural areas and did not follow municipal boundaries, but it was upheld by the Prince Edward Island Supreme Court in 1996.

Background

Prince Edward Island, located in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence and connected to mainland Canada (New Brunswick) by the Confederation Bridge, is Canada’s smallest constituent unit (province or territory) in land area and smallest province by population (the three territories have a smaller population than PEI). According to the 2011 Census, PEI’s population was only 140,204 – basically a medium-sized regional town (the Sherbrooke urban area in Quebec has a similar population), which also means that PEI’s electoral districts, with an average population of only 5,000 in each, are very small units comparable to municipal wards in most countries. The provincial capital, Charlottetown, has a population of only 34,562 (although the census agglomeration has 64,487 people. Summerside, the Island’s second-largest city, has a population of 14,751 and is the only other community on the Island with a population of over 10,000.

PEI is a fairly linguistically homogeneous province: 92% of residents in 2011 reported English as their mother tongue, with only 3.7% (or 5,190 people) saying French was their mother tongue and 3.5% with a non-official language as their mother tongue. 87% of Islanders are unilingual Anglophone and 95% speak English most often at home. The Francophone (Acadian) minority in PEI is largely concentrated in Prince County (the western third of the island), in the provincial district of Évangéline-Miscouche (where they may make up a majority of the population) and more specifically in three census subdivisions (Lot 15, Abrams Village and Wellington). In racial terms, PEI is also – unsurprisingly – quasi-homogeneously white, with visible minorities making up only 3.1% (4,260) of the population, with Chinese being the single largest minority group (with 1,830 people), and an additional 1.6% (2,230) claiming Aboriginal identity. The Mi’kmaq are, like in the other Maritime provinces, the main Aboriginal group in PEI, which has two First Nations reserves (both Mi’kmaq).

Islanders are largely of British Isles ancestries – Scottish, English or Irish. According to the 2011 NHS, 66.8% of residents claimed British Isles ancestry – more specifically, 39.3% claimed Scottish ancestry, 31.1% claimed English ancestry and 30.4% claimed Irish ancestry. PEI has the highest percentage of persons claiming Scottish or Irish ancestries of any province in Canada. Additionally, 36.8% claimed ‘Canadian’ ancestry and 21.1% claimed French ancestry. One of the more salient divides on the island has traditionally been religion (like in the other Atlantic provinces): PEI was 84% Christian as of 2011, with only 14.4% non-religious. Christians are fairly evenly divided between Catholics (42.9%) and the various Protestant denominations (41.1%, including 9.6% of ‘Other Christians’), and the United Church of Canada is the single largest Protestant denomination. Catholics and Protestants are fairly evenly spread throughout the island, although the eastern and western ends of the island (Kings and Prince counties) tend to be more Catholic while central Queen’s County is slightly more Protestant or non-religious (in Charlottetown, which is 20.8% non-religious).

PEI has the smallest economy of any province, contributing only 0.3% of GDP. The island, like most of the Atlantic provinces, has a weak economy which has been struggling for decades (in fact, the Maritimes’ best economic days, in general terms, were probably before Confederation). PEI has the lowest GDP per capita of any province ($39,780), and its median household income in 2011 ($55,311) was significantly lower than the national median HH income ($61,072). 59% of Islanders, in 2011, fell in the bottom half of the Canadian population (by income decile) and 15.8% were classified as low income (after-tax), compared to 14.9% of all Canadians. Only 82.2% of income came from ‘market income’, the second lowest in Canada (after Newfoundland), while 17.8% of Islanders’ income came from government transfer payments – including a full 5.8% from Employment Insurance (EI), compared to 1.8% across Canada. In April 2015, finally, PEI’s unemployment rate – 10.5% – was the third highest in Canada (after Newfoundland and Nunavut) and significantly higher than the national average (6.8%).

After Confederation, federal economic policies such as the National Policy primarily benefited the industrial powerhouses of central Canada and hurt the Maritimes, as did changing patterns of trade. Furthermore, PEI, an agricultural province lacking in natural resources and transportation links essential to industrial development, was unprepared for industrialization. The province, like the other Atlantic provinces of Canada, have benefited from post-1945 federal economic policies, social programs and transfer payments. In recent years, the provincial government has tried to break the province’s dependence on federal transfers by developing industries such as tourism. However, like the other Maritime provinces of Canada, PEI’s traditional dependence on federal funding and programs has meant that its provincial government has typically not been assertive or one to rock the boat in federal-provincial relations.

PEI was historically a predominantly agricultural province, thanks to its rich soil, ample supply of arable land and temperate climate. PEI is widely known across Canada for its potato production: in 2012, potatoes were the single most profitable crop, earning $246 million out of a total farm cash receipts of $467 million. The province is the nation’s largest supplier of potatoes. Fishing is also a major activity for the coastal communities. However, since the 1950s, the number of farms on the island has declined considerably and existing farms are large enterprises. In 2014, 8.4% of the labour force was directly employed in agriculture or fishing, which made it the fourth largest industry behind public administration (9.5%), retail trade (13.5%) and health care/social assistance (14.2%). Comparatively, across the country, only 3.8% of the labour force was employed in agriculture, forestry or fishing in 2014. Additionally, fisherman was the second most common specific occupation in 2011 (3.2% of the employed labour force), whereas across Canada it was ranked 219th and employed only 0.1%. Nowadays, public sector employment – public administration, education, healthcare and federal services – has replaced agriculture as the major employer on the island, alongside tourism (Anne of Green Gables, PEI’s red cliffs, beaches and unspoiled landscape), construction and light manufacturing (often primary resource-related).

The most common occupations (NOC) in 2011 were sales and services (22.4%), trades transport and equipment operators (15.3%), business finance and administrative occupations (14.9%) and occupations in education, law and social, community and government services (11.3%).

Political history

Prince Edward Island hosted the Charlottetown Conference in 1864, the first in a series of interprovincial conferences which would culminate in Canadian Confederation in 1867. However, the island declined to join Confederation immediately. By 1873, however, construction debts from the provincial railway threatened to bankrupt the colony, and the Liberal government of Premier Robert Haythorne sent a delegation to Ottawa to seek terms for admission to Confederation in return for the federal government assuming the colony’s extensive railway debts.

The other major issue in 19th century PEI was the land question. In 1767, Britain had divided the island into 67 lots owned by ‘proprietors’ (mostly absentee landlords in England) who collected rent from tenant farmers. The issue had been a hot button issue since the 1790s, but London blocked several attempts at land reform by colonial leaders prior to the advent of responsible government (1851). Afterwards, despite significant activism from tenant farmers, the cash-strapped and rather weak colonial government struggled to find a solution to the land question – which dragged on for over two decades after the introduction of responsible government. In 1873, one of the terms of joining Confederation was that the federal government would provide $800,000 towards the purchase of absentee landholdings on the island. In 1875, the province passed the Land Purchase Act, which made compulsory the sale of estates on PEI larger than 500 acres. To this day, non-residents are not permitted to purchase land on the island in excess of 2 hectares without approval from the cabinet.

The issue of separate schools – establishing a parallel system of separate Catholic schools – continued to divide the Liberals and Conservatives in island politics for a few years following Confederation, until 1876, when a coalition of Protestant Liberals and Conservative won power and created a non-sectarian, secular public school system.

With the three major political debates of the 19th century being settled within a few years, PEI politics moved towards the traditional political culture of the other Maritime provinces, characterized by parochialism, tradition, conservatism, pragmatism and a dose of cynicism and caution. Ideology has played a relatively minor role in PEI politics, and most observers have pointed out that few if any meaningful issues or ideologies divide the Liberals and the Conservatives. The parties reached their positions more on grounds of political expediency rather than principles, and they have always operated as patronage machines alternating in power rather than ideological parties. If the two parties were to be ideologically classified, both would end up in the centre, with the Liberals usually a bit more to the left and the Conservatives a bit more to the right.

Like in Nova Scotia, no great ethnic, religious, class or ideological antagonisms have had a strong, lasting influence on Island election. Religion has sometimes been identified as the main cleavage between Liberals and Conservatives, with the former being favoured by Catholics and the latter by Protestants, but PEI politics have never been sectarian and the parties have always had voters, members and leaders from both religious groups. Regionally, the Conservatives have usually been stronger in eastern Kings County and the Liberals in western Prince County, but this has hardly been a set rule: for example, in the 2008 federal election, the federal Conservatives (Gail Shea, a former provincial politician) was elected to the House for the western riding of Egmont while the Liberals retained the three other seats.

PEI is the Canadian province which has remained the most loyal to the old two-party (Liberals and Conservatives) system from Confederation. With the exception of independents elected in the first two provincial elections, no third party won a seat in the provincial legislature until the New Democrats (NDP) won a single seat in 1996, which they lost in 2000. No third party ever won over 10% of the popular vote, with the provincial NDP peaking at about 8% in the 1996 and 2000 elections.

Despite the little ideological differences between the traditional parties and the low stakes of most provincial elections, partisan identification and voter turnout have remained unusually high (turnout has almost always been over 80%, only falling to an historic low of 76.5% in 2011).

Since Confederation, Island politics have been dull to outside observers. The Liberals and Conservatives have alternated in power, and, with the exception of a series of one-term governments in the 1920s and early 1930s, all governments have been reelected at least once. However, neither party has managed to build a monopoly on power – no government has won more than three terms in office since 1978, when Premier Alex Campbell’s Liberals won a fourth (but final) term in office. After three terms in office, voter fatigue tends to set in and the governing party loses to the opposition, which campaigns on the vague promise of ‘change’ and open-ended criticism of some unpopular government decisions. The last change of government on the Island happened in 2007, when Premier Pat Binns’ Progressive Conservatives (PC) sought a fourth term but were soundly defeated by Robert Ghiz’s Liberals, who won 23 seats to the PCs’ 4 and won the popular vote 53% to 41%.

The relative social and political homogeneity of the Island has meant that elections, in terms of seat count, tend to be very lopsided, even if the popular vote has always remained quite close. Governing parties win huge majorities with the opposition being kept to a tiny caucus. The last time the seat count was close was in 1978 (the election split 17-15 between the Liberals and PCs).

Most PEI premiers since Confederation have been unremarkable, with few making a lasting mark by staying in power for a very long period of time or by attaching their names to landmark policies (which have been few in Island politics). Historically, many PEI premiers used the office as a stepping stone in their careers, leaving the job for a judicial appointment or an upgrade to federal politics. In the recent past, the most important PEI premiers have been Liberals Alex Campbell (1966-1978) and Joe Ghiz (1986-1993) and Tory Pat Binns (1996-2007). Alex Campbell supported government intervention in the economy to help diversify PEI’s mainly agricultural economy, and modernized some aspects of Island politics and institutions. Joe Ghiz gained some national notoriety by opposing free trade and supporting the two failed attempts at constitutional reform (Meech and Charlottetown). Pat Binns presided during fairly good economic times.

The provincial Liberals, led by Robert Ghiz – the son of former Premier Joe Ghiz – defeated the PCs in 2007. Remaining fairly popular throughout their first terms, the Liberals were widely expected to win a landslide in the 2011 election. However, the Liberals unexpectedly hit a bump, with a scandal involving the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP). The program allows provinces to nominate foreign nationals for entry to Canada, where they can fill local labour market needs. The PEI PNP program was set up in 2001 but shut down by Ottawa in 2008, after the federal government cracked down on years of irregularities in the province’s administration of the PNP. However, just as the program was about to be shut down, the province rushed through a large number of applications in order to maximize benefit from the embattled program. Immigrants invested their money into PEI businesses in return for immigrant status (for critics, ‘buying their way’ into Canada), but the program spun out of hand and a lot of the investment was pocketed by intermediaries and businesses who had no real relations with the immigrant-investors, while few immigrants actually moved to PEI. Relatives of the Premier, along with cabinet ministers, deputy ministers and several MLAs, benefited financially from the PNP. During the election campaign, the federal government called the RCMP and CBSA to investigate allegations of fraud and bribery in the PEI immigration program. Citizenship and Immigration Canada had received information from three former provincial public servants who claimed that would-be immigrant investors gave senior PEI bureaucrats cash-stuffed envelopes during a meeting in Hong Kong in 2008. Ghiz’s Liberals called the allegations politically motivated, but the opposition PCs went on the offensive in the hopes of shaking the government’s support. The RCMP investigation continued for three years but closed in January 2015 without any charges laid.

The PCs gained 5 points in polls in a month with the scandal, and probably spoiled Ghiz’s hopes of a clean-sweep of all 27 seats. In the end, the Liberals, however, were reelected with a barely reduced majority – 22 seats and 51.4% against 5 seats and 40.2% for the PCs. Once again, the provincial New Democrats or Greens failed to make any breakthroughs, winning 3.2% and 4.4% of the vote respectively.

In its second term, the Liberals have also been mixed up in another major scandal; a complicated e-gaming scheme. A number of islanders, including Ghiz’s close confidantes and the PEI conflict of interest commissioner, invested about $700,000 in a US-based tech firm which wanted to set up global banking platform on the island. The province had been trying to get into the online gambling business for some years, in the hopes of generating millions a year, but faced several thorny legal questions. Although the provincial government axed the e-gaming side of the deal due to legal and technical problems, it remained interested in turning the Island into a financial services hub. In 2012, it signed a MOU with a company which ended up embroiled in a securities investigation some months later. Questions have been raised about the conduct of current and former elected officials and staff.

The Liberals have also been criticized for the government’s poor record on the deficit. Since 2011, the Liberals have announced three successive deficit elimination plans, none of which have seen a successful conclusion. Before the 2011 election, the government announced that it would eliminate the deficit by 2013-14, but after they were reelected, the Liberals announced that the deficit was bigger than expected. In 2012, the government came out with another plan, aiming for a small deficit in 2014-15, instead of balance in 2013-14. The finance minister said increased costs of public pension were having a big impact on the budget. The Liberals’ 2012 plan announced 0% increases in all departmental budgets, with the exception of health (which would get a 3% annual increase), until the budget was balanced. In 2012, the Liberals broke a 2011 campaign promise by introducing the Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) to PEI, an introduction which would not be revenue neutral. Despite the introduction of the HST, the government’s budget presentation in 2013 announced a much larger budget deficit (missing the target by $25 million). The Liberals now aimed for balance in 2015-16. To raise revenues, the Liberals increased taxes on gas (by 9 cents) and adult clothing, previously exempt from the provincial sales tax. The limits on government spending also meant important cuts in post-secondary education.

2015 election: Campaign and issues

Premier Robert Ghiz somewhat unexpectedly announced his pending resignation as Premier in November 2014, the day after his government opened a new session of the legislature with a Speech from the Throne. In February 2015, the PEI Liberals acclaimed Wade MacLauchlan, the 60/61-year old former president of the University of Prince Edward Island (1996-2011), who is also openly gay (somewhat notable, perhaps, for a traditionalist and conservative province like PEI). None of the senior cabinet ministers in Ghiz’s cabinet stepped up, but instead they all lined up behind MacLauchlan, who ended up as the sole candidate in the race. MacLauchlan was a successful president at UPEI, but is a political rookie. Upon his selection as Premier, MacLauchlan introduced new conflict of interest regulations for politicians and signalled that he’d like the Auditor General to look into the e-gaming scandal. As an outs

PEI last voted in October 2011, and PEI’s fixed election dates law mandates that the next election should have been held on the first Monday of October. However, the newly-elected Premier was eager to seek a mandate from Islanders – and take on the opposition parties, especially the PCs, before they were quite ready – so he dropped the writ for an election on May 4.

Indeed, the PEI PCs went through a deeply chaotic period in 2013. Olive Crane, the PCs’ leader in the 2011 election, stayed on after the election defeat, but her party performed poorly in polls, which showed very high levels of support for the PEI NDP, up to 22% in December 2012 (just 6 points behind the PCs). In December 2012, she survived a leadership review but got a very poor result, which led to her resignation as Leader of the Opposition and PC leader in January 2013. The 5-member PC caucus elected Hal Perry, the MLA for Tignish-Palmer Road, as Leader of the Opposition. However, the PC party – the caucus and the executive – decided to elect Steven Myers, MLA for Georgetown-St. Peters as interim PC leader. Perry initially announced that he would stay on as opposition leader, but the situation became chaotic and ridiculous: the 5-member PC caucus had one MLA as party leader and another MLA as opposition leader. The Liberal Speaker recognized Perry as opposition leader, which added to the ridiculousness of the situation – the Liberals picking the PC leader for them. However, Perry was soon forced to resign his untenable position and Myers got both jobs, although with limited caucus support. The March 2013 CRA opinion poll showed the PCs, after their leadership troubles, down to disastrous third place with only 16% support against 51% for the Liberals and 26% for the NDP (which won, you’ll recall, all of 3.2% in 2011). The PCs climbed back up to second place with 22% in May 2013, but by August 2013, they had fallen back to third again with 23% against the NDP’s historic 32% and the Liberals’ 42%.

In October, the chaos in PC ranks started anew when the PCs lost two-fifths of their caucus within 48 hours. On October 3, Hal Perry crossed the floor to join the Liberals, officially citing the PCs’ reluctance to criticize the federal Conservatives’ changes to Employment Insurance. On October 4, Myers expelled Olive Crane from the PC caucus for rather long-winded reasons: basically, Crane spoke to the media about Perry’s departure when she wasn’t supposed to according to official PC directives. Crane continued to sit as an independent. The PCs, therefore, were down to 3 MLAs. In November 2013 and February 2014, the CRA polls again showed the PCs languishing in a horrible third with only 17% support while the NDP continued riding high at 26% and 22% support respectively.

The PCs brought forward their leadership convention after the Liberals elected their new leader (on February 21), holding theirs on February 28. In a contested race, the PCs elected outsider Rob Lantz, a Charlottetown city councillor, who defeated James Aylward, the MLA for Stratford-Kinlock who had the backing of interim PC leader Steven Myers and the other sitting PC MLA (Colin LaVie). Polls in 2014 had shown the PCs struggling with poor polling numbers, but pushing their way back into second as the NDP’s remarkable (but unrealistic) momentum wore off. In February of this year, CRA showed the Liberals enjoying very strong support (58%) after MacLauchlan’s coronation with the PCs a poor second (26%) and the NDP in a strong but weaker third (12%).

As usual, the Liberals and the PCs did not differ much on the major issues – healthcare, jobs, economy, education and the like – and mostly had the same positions phrased differently. The PCs mostly focused on change, running on the slogan ‘A New Direction’, and sometimes hitting the Liberals quite hard on ethics issues and promising “major governance reforms to increase accountability, transparency and open government.” The PCs also promise to rebate the 9% provincial portion of the HST on residential electricity and a 20% reduction in copay for seniors’ drugs. Both parties steered clear of the abortion debate – PEI is the only province in Canada where a woman still cannot get a surgical abortion (as there are no abortion providers on the island), instead she must go to Halifax (Nova Scotia). Neither the Liberals or the PCs are interested in opening up abortion services on the Island (although the NDP and the Greens are). Even federal Liberal leader Justin Trudeau, who has famously demanded that his MPs and candidate be prepared to cast pro-choice votes, sidestepped the issue of on-Island abortions when campaigning with MacLauchlan.

The PEI NDP and Greens both made a much stronger run than in any other election in the past. The PEI NDP, the weakest of all provincial New Democrats in the country, peaked at 8.4% of the vote in the 2000 election and won a seat in the Legislative Assembly only once – in 1996 – when then-NDP leader Herb Dickieson was elected in West Point-Bloomfield, a victory owed mostly to local issues at the time. In 2011, the NDP ran only 14 candidates and won 3.2% of the vote; as in 2007, it placed fourth, behind the Greens, who ran 22 candidates and obtained 4.4% of the vote. Both parties went into this election led by new, ambitious leaders. The NDP was led by Michael Redmond, who ran in Montague-Kilmuir against a Liberal incumbent. The Greens were led by Scottish-born dentist and perennial Green candidate Peter Bevan-Baker. The NDP put up a full slate of 27 candidates, while the Greens had 24 candidates. Unlike the NDP, the Greens followed the new federal and provincial Green parties strategy of putting the most resources in the leader’s riding (in this case, Kellys Cross-Cumberland), a strategy which notably saw the New Brunswick Greens elect their leader in a Fredericton riding in last year’s provincial election.

Results and Analysis

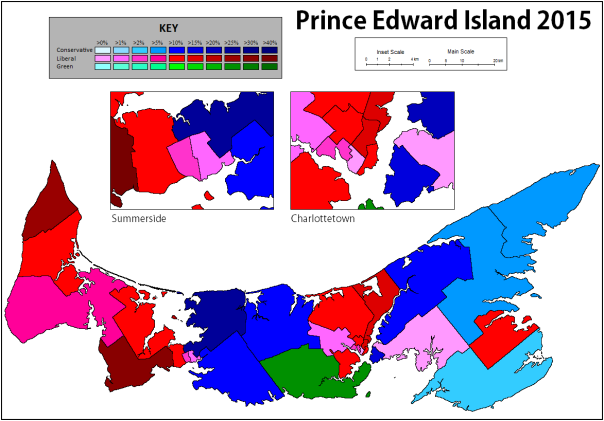

Turnout was 85.9%, up 10.5% from the last election, when turnout hit an Island low of 76.2%. Compared to 2011, this election was closer, more disputed, more open-ended (with the NDP and the Greens both making a much stronger run than in any other election).

Liberal 40.83% (-10.55%) winning 18 seats (-4)

PC 37.39% (-2.77%) winning 8 seats (+3)

Green 10.81% (+6.45%) winning 1 seat (+1)

NDP 10.97% (+7.81%) winning 0 seats (nc)

In one of the most exciting provincial elections in recent PEI political history, the Liberals were – as expected – reelected to a third term majority government, but they suffered significant loses and won a narrow majority with 18 seats out of 27 seats, a loss of 4 seats compared to the 2011 election. While in terms of seats the main beneficiaries of the Liberals’ loses were the opposition Tories, who gained 3 seats and now form a much stronger official opposition caucus of 8 (up from 5 in 2011 and 3 at dissolution), in terms of vote share the PCs did rather poorly as well, losing about 3% of their vote from the 2011 election. That being said, given how terrible the PCs did in opposition and how they managed to climb out of chaos only a few short months ago and elect a permanent leader only two months before the election (after 2 years with an interim leader), they should be pleased with their performance. In fact, the main winners of this election were the third parties – the NDP and the Greens. The Liberals’ 40.8% was the lowest vote share for a winning party in Island history, the Tory vote is the lowest it’s ever been since 1989 and above all the combined Liberal and Tory vote share – 78.22% – is the lowest in Island history.

The NDP and the Greens, together, won an amazing 21.78% of the vote, a remarkable feat in PEI. Naturally, both the NDP and the Greens won their best popular vote results in their (short, especially for the Greens) history, both winning nearly 11% of the vote. The NDP and the Greens’ results show that Islanders were displeased with both Liberals and Tories – one an unpopular governing party with a few ethics problems, the other an uninspiring and bland opposition party – and that some of them, for the first time, looked for an alternative to the two traditional parties in the NDP or the Greens.

However, of the two third parties, the Greens had the better election – even if they placed fourth in vote share, they won a seat, with an astonishing landslide for Green leader Peter Bevan-Baker in his riding of Kellys Cross-Cumberland (23% of all Green votes on the Island were cast for Bevan-Baker!). On the other hand, the NDP won more votes than the Greens and were generally stronger than the Greens in ridings where both parties competed against each other, but the NDP once again fell short of actually winning a seat. NDP leader Michael Redmond had a decent result in Montague-Kilmuir (23%), but he still ended up in third place in that rural Kings County seat which isn’t natural Dipper country; the NDP came within 109 votes in Charlottetown-Lewis Point.

This is very reminiscent of what happened last year in New Brunswick: the NDP stronger than the Greens in terms of votes, but the Greens coming out as the stronger of the two because they managed to elect their leader to the legislature while the NDP remained shut-out. The Greens, as in the federal election (2011), BC (2013) and NB (2014), used the successfully tried-and-tested strategy of dumping their scarce resources on the leader’s seat (or, if not, a limited number of seats, as in BC 2013) and going all-out there. In Canada’s FPTP system which really hurts a party like the Greens, this strategy has proven to be very successful for the Greens. The NDP, in provinces like PEI and NB where it is very weak and has the same FPTP issues as the Greens there, hasn’t really gone for the same strategy as the Greens and they’ve paid the price.

The PCs did best in Kings County/eastern PEI, holding the four seats they were defending there (including retiring ex-PC MLA Olive Crane’s riding) and gaining the marginal riding of Belfast-Murray River from the Liberals. Belfast-Murray River was former PC Premier Pat Binns’ seat, which the Liberals gained in a 2007 by-election (after Binns stepped down after his defeat) during their long honeymoon and held by only 8 votes in the 2011 election. This year’s race, a rematch of the 2011 contest between Liberal MLA Charlie McGeoghegan and PC challenger Darlene Compton, went in the Tories’ favour, who won the seat with a more comfortable margin of 108 votes. The Liberals held Vernon River-Stratford by a tiny margin of only 2 votes for Liberal incumbent Alan McIsaac on election night. After a recount, the result there actually ended up as a perfect tie, and the Liberals only won the seat by coin toss. The Liberals had an easier time in Montague-Kilmuir, winning 41.8% against 31% for the PCs and 23.1% for NDP leader Michael Redmond. Compared to the NDP’s results in surrounding districts (7-9%), this was a strong performance for the NDP, but they still fell short by a good distance.

The PCs also had good results in rural central PEI (Queen’s County), a key swing region where elections are won. The Tories gained Borden-Kinkora, Kensington-Malpeque and Rustico-Emerald from the Liberals (incumbents standing down) – with fairly consequential margins in all three. Liberal leader and Premier Wade MacLauchlan was elected in his riding of York-Oyster Bed, with a 600 vote victory over the Tories (47.7% to 32.9%) while the Liberals also held the Charlottetown suburban districts of Cornwall-Meadowbank (46.3% to 33.8%) and Tracadie-Hillsborough Park (45.7% to 27.8%). However, the Liberals held the other suburban district, West Royalty-Springvale, by only 59 votes against the PCs. In Kellys Cross-Cumberland, a predominantly rural/small town riding on the south-central coast of PEI, Green leader Peter Bevan-Baker saw his hard work pay off, winning in a shocking landslide – a margin of 1,031 votes, taking 54.8% of the vote against only 27.6% for the Liberal incumbent. In fact, Bevan-Baker’s margin of victory (in terms of votes, not percentages), was the largest of any winning candidate on the island!

Of decisive importance to the Liberal victory was Charlottetown – where they won every seat, despite tough challenges in a number of them and loses in most. In Charlottetown-Brighton, one of the key races of the election, Liberal candidate Jordan Brown defeated PC leader Rob Lantz by a 24-vote margin (39% to 38.1%). In Charlottetown-Lewis Point (many students from UPEI live in this district), the Liberals held on despite a tough challenge from the NDP – the NDP lead for a good part of the night, but the advance polls won it for the Liberals, by a thin 109 vote margin (34.3% to 30.7% for the NDP, with 27% for the PCs). The Liberals didn’t sweat as much in Charlottetown-Victoria Park, Charlottetown-Parkdale and Charlottetown-Sherwood. However, the Greens did win some very good results in Charlottetown-Victoria Park (18.8%) and Charlottetown-Parkdale (19.2%), winning a number of polls in both (in the downtown core areas and surrounding areas, with a young population, and gentrified low-income areas)

The Liberals swept western PEI, and won tight but decisive victories in the two districts of Summerside, PEI’s second-largest city. In Summerside-St. Eleanors, the Liberals won by 148 votes against the PCs, while in neighbouring Summerside-Wilmot, Liberal MLA Janice Sherry was reelected with a lead of only 30 votes against the Tories. The Liberals had an easier time in Tyne Valley-Linklater (337 vote victory) and O’Leary-Inverness (247 vote victory), while their incumbents won by big margins in Évangéline-Miscouche (62.6% for Liberal MLA Sonny Gallant in PEI’s Acadian riding), Alberton-Roseville and Tignish-Palmer Road. In the latter, floor crosser incumbent Hal Perry – elected as a Conservative in 2011 but running for reelection as a Liberal this year – was handily reelected, with a 668 vote lead and some 58.2% of the vote.

The Liberals won four districts by less than 100 votes (including one by only 2 votes) – if the PCs had won them, they would have held 12 seats to the Liberals’ 14, a wafer-thin majority for the Liberals. If the Liberals also lost the two other ridings which they won by less than 200 votes, we’d be looking at a Tory minority government and a Legislative Assembly with 13 Tories, 12 Liberals, 1 Dipper and 1 Green.

PEI political history dictates that the Liberals will be defeated as they try to win a fourth term in 2019. In the meantime, however, the PCs – who, in spite of everything, remain the only alternative governing party on the Island – will need to manage their time in opposition far better than they have since 2011. Rob Lantz turned out to be a strong and competent leader on the campaign trail, who managed the PCs well after the chaos of 2013, but unfortunately for them he was narrowly defeated in his own bid to enter the Legislative Assembly, although he will remain (for now) as the PC leader from the outside. The PCs will also need to deal with this potentially tricky situation. As for the third parties, the NDP comes out with a strong showing but also a frustrating and disappointing end result, while the Greens come out with a foothold in the legislature for their amiable and popular leader, and will thus have a stronger voice than the NDP. However, neither the NDP or the Greens can be seen as realistic alternative governing parties for the Island (although this is Canada we’re talking about, and considering I’m about to talk about Alberta’s election…).

Alberta

All 87 members of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta, the unicameral provincial legislature of the province, were up for reelection. Members – styled MLAs – are elected by FPTP in single-member constituencies (or ridings).

Background

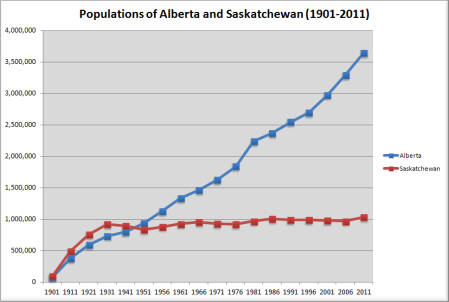

Alberta, located in Western Canada and bordered by British Columbia (to the west, across the Rocky Mountains), Saskatchewan (to the east), the United States (to the south) and the territories (to the north), is Canada’s fourth-most populous province – after Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia. According to the 2011 Census, Alberta had a population of 3,645,257 while the latest population estimates for the first quarter of 2015 pegged Alberta’s population at 4,160,044 – or 11.7% of the total Canadian population. Between 2006 and 2011 and again between 2011 and 2014, Alberta had the second highest population growth rate of any jurisdiction in Canada – +10.8% from 2006 to 2011 (only Yukon had higher growth) and +13.7% from 2011 to 2014 (only Nunavut had higher growth). In the past 100 and 50 years, mainly because of its burgeoning economy, Alberta’s population has grown dramatically – in 1911, Alberta’s population was a mere 374,295 and in 1966, Alberta’s population was 1,463,203.

The Albertan population is one of the most mobile in the country: in 2011, 44.9% of Albertans lived at a different address than they did 5 years ago, compared to 38.6% of Canadians. 6.5% of Albertans in 2011 were interprovincial migrants (lived in a different province 5 years before), compared to only 2.8% of the Canadian population in 2011. Alberta’s strong economy and employment opportunities have famously attracted Canadians from other provinces, most notably the Atlantic provinces. Only 53.6% of the population in 2011 was actually born in Alberta, compared to two-thirds of Canadians who were born in the same province that they resided in.

Alberta has two major cities, Calgary and Edmonton. In 2011, the Calgary CMA had a population of 1,214,839 while the Edmonton CMA had a population of 1,159,869 – taken together, 65% of Alberta’s population in 2011 lived in these two metropolitan areas, which have also seen rapid population growth throughout the 20th century and particularly in the last 10-15 years. The relatively equal weight of the two cities has produced a lasting political, economic and sports rivalry between them, with began when Edmonton was selected as the provincial capital over Calgary in 1905. Other large cities in Alberta include Red Deer (90,564) in the Calgary-Edmonton corridor, Lethbridge (83,517) in southern Alberta, St. Albert (61,466) in the Edmonton CMA, the oil boom town of Fort McMurray (61,374) in northeastern Alberta, Medicine Hat (60,005) in southeastern Alberta and Grande Prairie (55,032) in northwestern Alberta.

Compared to the rest of the country, while Alberta is aging it has of the youngest populations in Canada – in 2011, the lowest median age (36.5) and the lowest percentage of the population aged 65+ (11.1%).

Alberta is Canada’s third largest economy, contributing 17.9% of the national GDP. The province’s economy is famously driven by oil – Canada is now the world’s fifth largest producer of oil, and Alberta is the largest producer of conventional crude oil, synthetic crude and natural gas in the country. More importantly, Alberta has the largest reserves of unconventional oil in the world – in the form of the oil sands (or tar sands), found mostly in the Athabasca region in northeastern Alberta. Oil sands now account for the vast majority of Canada’s rapidly increasing oil production: of the 173 billion barrels of oil that can be recovered with today’s technology, 168 billion of those are found in the oil sands (giving Canada the third largest proven crude oil reserves in the world). Conventional oil production in Alberta began in earnest in 1947, a date which marks the beginning of the oil era in Alberta’s economy. Because of the high cost of developing the oil sands and the difficulty of extraction (today, most oil sands extraction in Canada require advanced in situ technologies in most cases), commercial production has only become viable when the price of oil is high. Commercial production of oil from the Athabasca oil sands only began in 1967, but only took off with rising oil prices since the late 1990s and early 2000s. Since the 1960s, Alberta’s economy has followed the oil cycle, doing well when oil prices have been high but struggling when oil prices fall. Therefore, Alberta’s economy was doing very well between the late 1990s until 2008.

Alberta has the highest GDP per capita of any province ($84,390) – only the Northwest Territories, with a far smaller population and due to its booming diamond mining industry, has a higher GDP per capita in Canada. Moreover, its median household income in 2011 ($78,632) was the highest of any province, significantly higher than the national median HH income ($61,072). Calgary and Edmonton are two of the most affluent metro areas in the country, along with Ottawa-Gatineau.

60% of Albertans, in 2011, fell in the higher half of the Canadian population (by income decile), with 17% in the highest decile. 10.7% were classified as low income (after-tax), compared to 14.9% of all Canadians. 92.7% of incomes in 2010 came from market income, the highest of any jurisdiction in Canada, and only 7.3% came from government transfer payments. In April 2015, Alberta’s unemployment rate – 5.5% – was below the national average (6.8%), tied with Manitoba for the second lowest unemployment rate behind Saskatchewan. Although low compared to other provinces, Alberta’s unemployment rate has been increasing in the last few months and is quite a bit higher than what it used to be during pre-recession boom days – in 2006, for example, unemployment was as low as 3% in the province. In March 2015, 38,750 people received regular Employment Insurance (EI) benefits in Alberta, up 24.7% on the previous year (by comparison, the number of beneficiaries rose by 0.5% in Canada over the same period).

Alberta has always been an export-oriented economy, but the economy has changed substantially as different export commodities have risen or fallen in importance. Over the province’s history, the most important products have been fur, wheat and beef and oil and gas. With the expansion of the railway to Western Canada in the late 19th century, commercial farming – mostly wheat farming – became viable and replaced fur trading as Alberta’s main industry. Agriculture dominated the Albertan economy from around the time it joined Confederation in 1905 until the expansion of the oil and gas industry in the 1950s. Naturally, the changing nature of the Albertan economy has had major impacts on Albertan society, culture and politics. Various authors, for example, have explained Alberta’s unique political culture partly in terms of believed shared interest in a single dominant commodity (Gurston Duck’s ‘Alberta consensus’ theory) or supposed class homogeneity (C.B. Macpherson’s Democracy in Alberta).

In 2014, mining, quarrying and oil and gas extraction contributed the largest share – 27.4% – of Alberta’s GDP, followed at some distance by construction (10.7%) and real estate (9.5%). The top industries in terms of employment in 2011 were elementary and secondary schools (4.1%), hospitals (3.5%) – like across Canada – but 3.3% were directly employed in oil and gas extraction and another 2.9% in support activities for oil and gas extraction, making them the third and fourth most important industries in Alberta, whereas they only rank 55th and 49th nationally. An above average percentage, compared to Canada as a whole, were also employed in architectural, engineering and related services (2.8%) and farms (2.7%). Using NAICS industries, the largest general industries in 2014 were construction (11.3%), health care and social assistance (10.6% of the labour force), retail trade (10.3% of the labour force) and professional, scientific and technical services (8.1%). Compared to Canada as a whole, a large percentage, unsurprisingly, were employed in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction (7.7%; 1.7% in Canada); vice versa, manufacturing and public administration were less significant employers than in the wider country.

In 2011, the most common occupations (NOC) were sales and services (20.7%), trades transport and equipment operators (17.4%), business finance and administrative occupations (16.4%) and management occupations (11.7%).

As with all of Western Canada outside of Manitoba, in terms of official languages, Alberta is overwhelmingly Anglophone: in 2011. 77% reported English as their sole mother tongue and only 1.9% reported French as their sole mother tongue; 92% spoke only English and 85.7% spoke English most often at home. The town of St. Paul, first settled by French missionary activity, has the largest French-speaking population Alberta, making up 15% of that town’s population. While Alberta’s Francophone population is very small, it has a growing immigrant population who speak a non-official language as their mother tongue (19.4%) and at home (10.5%).

18.4% of the population in 2011 were visible minorities, only slightly less than the national average; the largest visible minority groups in Alberta were South Asians (4.4%; mostly Punjabi), Chinese (3.7%), blacks (2.1%) and Filipinos (3% – significantly above the Canadian average). Nearly 11% of all immigrants in Alberta were born in the Philippines and Tagalog had become the third biggest non-English mother tongue in the province after German and French, a sharp increase on 2001 and 2006. Visible minorities make up 22% of the population in Edmonton and 28% in Calgary.

Alberta’s white population is also very diverse in terms of ancestry. The most common ethnic origin in 2011 was English (24.9%), a percentage significantly higher than the Canadian average, followed by ‘Canadian’ (21.8% – over 10% below national average), German (19.2% – nearly 10% above the Canadian average), Scottish (18.8% – also above average), Irish (15.8%), French (11.1%), Ukrainian (9.7%) and Dutch (5.1%). Alberta, like other Western provinces, sticks out by its large proportion of Ukrainians (who make up only 3.8% of the Canadian population), Dutch and Scandinavians. The federal Liberal government under the direction of Minister of the Interior Clifford Sifton (1896-1905) allowed for non-British white European immigration to settle Western Canada, the ‘Last Best West’ in the 1890s following the closing of the American frontier. Ukrainians and others mostly settled in ‘ethnic block settlements’, many of them in northern Alberta.

The closing of the American frontier also led to significant American immigration from the United States – English-stock Americans, Canadians who had moved to the US but returned north, European-stock immigrants to the US. In 1916, Americans accounted for 36% of all foreign-born residents of Alberta (and 30% of those in Saskatchewan, but only 8% of those in Manitoba – far more influenced by English Ontarian settlement). Americans mostly settled in rural southern Alberta, while the cities – Calgary and Edmonton – were mostly settled by British immigrants; American immigrants tended to be farmers looking for land in Canada, while British immigrants tended to be workers and/or urban-dwellers. Nelson Wiseman (2011) showed how American immigrants to Alberta have had a significant impact on the province’s political culture, especially in its infancy years.

Alberta is contradictory in religious terms. Evangelical Christianity is important and has played a significant role in its politics, but Alberta is the second-most non-religious province in Canada after BC, with 31.6% of Albertans in 2011 not reporting a religious affiliation compared to 24% of Canadians. 60.3% are Christians, divided between 24% of Catholics, 7.5% of UCC adherents, 3.9% of Anglicans, 3.3% of Lutherans and a large percentage identified as ‘other Christian’ (15.2%). Alberta has Canada’s only significant Mormon population, around Cardston in southern Alberta, who are mostly descended from pioneers who emigrated from Utah. There are also significant numbers of Mennonites, Hutterites, Seventh-day Adventists and evangelical Protestant denominations. The ‘other Christian’ grouping likely includes non-negligible numbers of Eastern Rite Churches – Ukrainian Catholics, Ukrainian Orthodox etc.

There is also a significant Aboriginal population in Alberta – in 2011, 6.2% of residents claimed Aboriginal ancestry, which is higher than the national average (4.3%); most of them being First Nation (3.3%, Cree being the most important tribal group) and Métis (2.7%).

Political history

Alberta has a unique and distinctive political culture and history which sets it apart from the rest of Canada and has generated loads of academic debate. The province is most notable for its dynastic politics – up until this election, four parties have ruled Alberta, each for fairly long period of times: the Liberal Party (1905-1921), the United Farmers (1921-1935), Social Credit (1935-1971) and the Progressive Conservatives (since 1971). There have been no one-term governments (in fact, no government has served less than 3 terms) or minority governments in Alberta. No party which has lost power has ever regained power – in fact, of the three former governing parties, two of them (the UFA and SoCred) basically died out only a few years after their defeat. It can be said that Alberta has had a dominant-party system since entering Confederation in 1905.

C.B. Macpherson (1953)’s Democracy in Alberta described Alberta as having a unique ‘quasi-party system’ – incorporating elements of an ordinary party system, a nonparty system and a one-party system while having significant differences with all of them. In his Marxist analysis, Alberta’s party system was the result of its purported ‘relatively homogeneous class composition’ as an agrarian petit bourgeois society and its quasi-colonial relationship with central Canada. However, Alberta’s party system has never been so unique: large legislative majorities for governing parties are the products of FPTP, there has never been political unanimity in Alberta, political longevity in Canadian politics is by no means limited to Alberta and the dramatic rise of the UFA and SoCred is not particularly unusual in Canada’s political system prone to large swings. Furthermore, Alberta could never have been described as a ‘relatively homogeneous’ agrarian petit bourgeois society – not even in the 1930s, and certainly not by the 1950s. The argument about the West’s ‘quasi-colonial’ relationship with central Canada is more valid, and ‘Western alienation’ has been a major theme in Alberta politics – past, present and future. However, while Albertan governments since 1921 have made use of Western alienation, it was never SoCreds or the PCs’ raison d’être.

More recently, Nelson Wiseman (2011) described Alberta as having a distinctive ‘liberal-individualist populist’ ideological orientation, which he argues is the result of American immigration to Alberta. While Alberta has undeniably been influenced by the general political culture of English Canada, and in general Albertans do not differ as much in their political views as is often imagined, some characteristics of America’s classical liberal ideology – rugged individualism, free market capitalism, egalitarianism and hostility towards centralized federalism – have been important in Alberta’s political culture. At the same time, Alberta has been less influenced by the central Canadian/British traditions of Toryism and later socialism, especially in comparison to Manitoba – a province built firstly by Ontarian settlers, unlike Alberta, a province built by the quasi-simultaneous immigration of a large array of ethnic groups. Nelson Wiseman argues that American immigrants to Alberta (who were mostly of English, rather than European, descent, and thus of higher social status) at the turn of the last century shaped early Alberta’s political culture – particularly its liberal, individualist and populist streak. The American influence was particularly strong in the 1920s agrarian movement in Alberta, the UFA. Henry Wise Wood, the president of the UFA from 1916 to 1931 (and the éminence grise behind the UFA in government), was born in Missouri and active in the US Populist movement in the late 19th century before moving to Canada at age 45. The Non-Partisan League from North Dakota expanded into Canada, but was only somewhat successful in Alberta, and was absorbed by the UFA in 1919. The UFA’s ideas were influenced by the American populist and progressive movements – direct democracy, proportional representation, monetary reform – which were anathema to central Canadian (and Manitoban) Tories and Grits alike. The difference could be seen within the Canadian progressive movement – Thomas Crerar’s Manitoba Progressives were former Liberals who wanted to ‘moralize’ the federal Liberals and supported the Westminster parliamentary system, the Albertans were more radical populists who rejected the party system and the parliamentary system. Geographically, the UFA and later SoCred performed best in rural southern Alberta, the region most heavily settled by Americans, while Edmonton and especially Calgary – mostly settled by the British – resisted these two movements, preferring the traditional parties and later the socialist movement (mostly built by Scottish and English immigrants in the British Fabian tradition).

The SoCred movement was also heavily influenced by evangelical Christianity (and not the Canadian social gospel of the CCF/NDP), and Mormons were important in the party – Solon Low, the SoCred federal leader from 1944 to 1961, was a Mormon. Although both the UFA and SoCred were populist movements hostile to big business and finance, and the UFA had collectivist ideas, both were – on the whole – liberal and individualist movements. Certainly SoCred, under Ernest Manning, became a socially conservative party hostile to big government and socialism. In more recent years, Wiseman pointed to the Reform Party/Canadian Alliance as influenced by modern American conservatism and the Republican Party. In the 1990s, the so-called ‘Calgary School’ group of conservative academics – including American-born Tom Flanagan and Ted Morton, among others (including Stephen Harper, active in the late 1990s in conservative academia) – expressed a low-tax, small government, anti-centralized government, free-market libertarian/conservative ideology quite similar to American conservatism.

Certainly, Alberta’s ‘liberal-individualist populism’ – if you accept that label to be an accurate descriptor of Alberta’s political culture – sets it apart from eastern and central English Canada, but also neighbouring Saskatchewan – the cradle of agrarian socialism, the first socialist government in North America in 1944 and what Wiseman described as a more collectivist populism.

Liberal era (1905-1921)

Alberta was created as a province, alongside Saskatchewan, out of the Northwest Territories in 1905. Under the terms of the Act which brought Alberta into Confederation, the federal government would retain ownership over natural resources and imposed requirements for separate schools, two terms which were already highly controversial in 1905 and became even more contentious in later years. The federal Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier, as expected, selected a Liberal as Alberta’s first lieutenant-governor, who in turn appointed a Liberal as the first Premier of the province – Alexander Rutherford. The dominant figure of Northwest Territories politics and leading lobbyist for provincial status (although one instead of two provinces), Frederick W.A.G. Haultain, was ‘snubbed’ because he was a Conservative. Although elected from Alberta, Haultain opted to lead the opposition to the Liberals in Saskatchewan rather than Alberta. Therefore, in Alberta, Rutherford’s Liberals, with the benefits of incumbency (patronage) and attacking R.B. Bennett’s Conservatives for their ties to the widely disliked Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), were returned in a landslide with 22 seats to the Conservatives’ 3.

Rutherford set up the main provincial institutions and, despite the Liberals’ usual aversion to government interventionism, made some large-scale forays into telecommunications by investing in a public telephone system and offering loan guarantees to several companies in exchange for commitments to build railway lines. Although disinterested by labour issues, the government intervened to moderate a major labour dispute in the coal mines in 1907, by setting up a commission and legislating a eight-hour day and workers’ compensation. Early in the government, Rutherford alienated Calgary by selecting Edmonton as the provincial capital and added to injury by later ensuring that the new University of Alberta would be in Edmonton (Strathcona). The popularity of the Liberals’ public telephone system carried them to an increased majority in 1909.

However, Rutherford began facing inconvenient questioning from a Liberal backbencher over very generous loan guarantees given to a railway company it knew little about and which had fulfilled virtually none of its promises regarding construction of the railway. The Conservative opposition accused the government of culpable negligence in failing to properly oversee the company’s activities. Bennett claimed that due to the discrepancy in the sale price of the bonds and what the government had received for them meant that the company had made a profit of $200,000-300,000 at the government’s expense. The scandal divided the government – the public works minister resigned as the scandal broke because of his disagreements with Rutherford – and the Liberal caucus. A number of Liberal MLAs voted in favour of a motion of no-confidence. Rutherford failed to quell the controversy with the appointment of a royal commission; the federal Liberal government and the lieutenant-governor intervene to force Rutherford to resign, which he reluctantly did in May 1910. He was replaced by Arthur Sifton, the former provincial chief justice, who had a veneer of impartiality and probity. Sifton repudiated Rutherford’s railway policy, in part, by passing legislation to confiscate the proceeds of the sale of government-guaranteed bonds sold to finance the controversial railway’s construction.

Sifton tried to restore party unity, but Rutherford stayed on as a backbencher critical of his successor. In the 1913 election, although renominated as a Liberal in his Edmonton riding, Rutherford effectively rejected the party label at his nomination meeting and even offered to campaign for the Conservatives (who rejected his offer, ran a candidate against him who ultimately defeated him). Sifton’s Liberals were reelected in 1913 but with a significantly reduced majority, while the Conservatives formed a strong opposition force with 17 MLAs against 38 for the Liberals.

Sifton’s tenure as Premier corresponded to the rise of the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA), which was still a farmers’ lobby group, although one with a very large membership and thus a force to be reckoned with. Sifton’s policies were increasingly driven by the UFA. Responding to UFA demands, he built agricultural colleges, allowed municipalities to levy property taxes (and required that rural municipalities tax only land), scrapped plans to privatize hail insurance and incorporated the Alberta Farmers’ Co-operative Elevator Company – a farmer-owned grain elevator company. The UFA also supported political reform – direct democracy, recall, women’s suffrage, so they influenced the Liberal government to pass a ‘direct democracy act’ (1913) which allowed for voters to call a referendum directly by submitting a petition including the names of eligible voters representing 10% of votes cast in the previous general election (and at least 8% in each of the provincial ridings), so a very high number of signatures. The law did not allow for recalls, as the UFA supported. One of the issues which did gather enough signatures for a citizen-initiated referendum was prohibition, which was voted on in 1915 and passed by a wide margin (61% yes) leading to the introduction of prohibition legislation in 1916. Sifton dragged his feet on women’s suffrage and made ridiculously sexist comments on the topic, but feeling pressure from women’s groups and the UFA, he committed to a debate on the issue and women gained the right to vote in 1916.

The Liberals were reelected in 1917, in the midst of World War I and the conscription debate in Canada. The election was fairly low-key – under an amendment to the election law, incumbent members who had signed up for war service were automatically reelected by acclamation (7 Liberals and 5 Tories were reelected this year). Overall, the Liberals won a reduced majority, with 34 seats against 19 for the Conservatives. The election saw competition from the Non-Partisan League (NPL), which originated in North Dakota and called for a ‘business administration’ and the election of a ‘truly people’s party’ rather than a traditional ‘party administration’ – a characteristically non/anti-partisan, grassroots populist discourse later adopted by the Canadian/Albertan agrarian progressive movement. Two NPL candidates were elected, while a Labor candidate was also elected from Calgary. The Albertan labour movement was led by Scottish-born William Irvine, a follower of the social gospel and later an advocate of UFA political participation. Sifton, however, resigned shortly after his reelection to serve as a cabinet minister in Prime Minister Robert Borden’s wartime pro-conscription Unionist government.

The conscription crisis divided Canada and the Alberta Liberals. While most Alberta Liberals backed Borden’s Tories in his pro-conscription coalition government, a significant number of them remained loyal to Laurier’s anti-conscription Liberals. Sifton was replaced as Premier by Charles Stewart, who also supported conscription.

Stewart continued to deal with the UFA, on issues like irrigation and a stillborn committee to look into proportional representation, but relations soured as the UFA had less success in driving the Liberal agenda during World War I.

United Farmers era (1921-1935)

Across Canada, farmers movements like the UFA hotly debated whether or not they should participate in politics and contest elections themselves. Western farmers had several reasons to be unhappy with the Canadian political system and the two major political parties. The National Policy, which imposed high tariffs on the import of manufacturing goods to protect central Canadian industries, was forcing Western farmers to sell their agricultural products at lower prices, and buy farm equipment and manufactures from central Canada at higher prices. At the federal level, low tariffs or free trade were the farmers’ main demand. Other complaints included the CPR high rates and the behaviour of private grain traders. Farmers grew to resent both the Liberals and Conservatives as corrupt central Canadian parties, which did not represent them or their interests – something which became especially true when the Liberals lost their enthusiasm for free trade after the defeat of reciprocity in 1911. In Alberta, UFA leader Henry Wise Wood believed that the UFA should exist only as a farmers’ interests organization om the principle of ‘group government’ – where government would function through the representation of major groups in society with direct democracy. The UFA distrusted traditional parties in part because they aggregate interests, dominated by elite powers who had no interest in extending democracy. The pressure from the NPL in the 1917 election and after the NPL merged with the UFA in 1919, led the UFA to reluctantly allow candidates to run in elections although ultimately leaving that decision in the hands of local branches. The UFA had a vast network of branches throughout the province, a sort of proto-constituency associations. In 1919, the UFA won a by-election in Cochrane from the Liberals, an event which marked the end of the fuzzy UFA-Liberal détente and the beginning of the UFA’s rapid ascent to power. The former leader of the Conservative Party, hitherto the main opposition to the Liberals, crossed the floor to join the UFA in 1920 and created a major split in Tory ranks which would cripple them for years to come. Ironically, Stewart was a member of the UFA and broadly sympathized with the UFA’s aims (and Stewart was fairly well regarded by the UFA leadership), but he opposed the UFA’s political vision and its political participation.

Provincial elections were held in July 1921. Just before the election, the Liberals were hit by a scandal, in which it was learned that the government spent money to have telephone poles crated and shipped in big stacks to remote communities in which they had no intention of installing phone lines in an effort to win support. The 1921 campaign was rather peculiar by any standards. The UFA ran candidates in only 45 of the 61 ridings – most notably, they ran no candidates in Calgary (which now elected five members using block voting) and only one candidate in Edmonton (which now elected five members using block voting), they had no leader (Henry Wise Wood did not run in the election, and neither did the man who would eventually become Premier) and had little in the way of a proper platform (besides opposing ‘partyism’, caucus secrecy and cabinet domination favouring instead direct democracy). Nevertheless, the United Farmers swept the province, winning 38 seats to the Liberals’ 15. The Tories were crushed, holding on to just one seat, while 3 independent and 4 Dominion Labor candidates were returned. In the popular vote, the Liberals won more votes than the UFA, 34.1% to 28.9%, but because the three main cities (Calgary, Edmonton, Medicine Hat) elected members by block voting in multi-member ridings, voters there had up to 5 votes (in Calgary and Edmonton) while rural voters had only one vote in FPTP single-member districts. The UFA also ran less candidates than the Liberals – overall, all but 7 of the 45 UFA candidates won, while 46 of the Liberals’ 61 candidates lost. A few months later, the Progressives/UFA won 10 of the 12 federal seats in Alberta in the 1921 federal election. Both the Tories and the Grits were shut out.

Henry Wise Wood, the president of the UFA, declined becoming Premier, preferring to operate the UFA machinery and the movement. The UFA settled on Herbert Greenfield, the UFA vice-president and an English-born farmer who reluctantly agreed to take the job. Greenfield was not a politician and had troubles controlling his caucus, which included a large number of radical backbenchers who opposed the parliamentary system. In early caucus meetings, Greenfield was challenged to include several Liberals in his cabinet, lest the UFA was to become like other political parties and in a naive hope of encourage sufficient cooperation to kill off notions of an ‘official opposition’. In handling the restless UFA backbenchers, Greenfield turned to his Attorney General, John E. Brownlee, an Ontarian-born lawyer and the UFA’s former solicitor. Brownlee would quickly rise to prominence because of his legal acumen and become the de facto leader of the government. Brownlee provided Greenfield with invaluable support and counsel, and the government relied on him in the legislature, where the Liberals formed a strong opposition. Brownlee led the UFA’s conservative faction – that is to say, the more traditionalist moderates who urged the UFA to reconcile with parliamentary government and tempered the more radical ideas of the backbenchers (like passing a motion which declared that only motions explicitly declaring a lack of confidence in the government should be treated as confidence votes, or the creation of a provincial bank). Brownlee also pushed for fiscal conservatism, advocating for deep spending cuts to reduce the large budget deficit.

Brownlee played a leading role in most of the first UFA government’s main initiatives. On agricultural issues, Brownlee pushed passage of legislation which created a drought relief commission to help indebted and drought-stricken southern Alberta farmers manage their debts with lenders. He played a central role in the creation of the Alberta Wheat Pool in 1923. For years, Western farmers had protested the private grain trade, as they suspected grain traders of being middle men who profited by leeching off the efforts of farmers and believed that they were artificially holding down prices. Wheat pools, farmer-owned cooperatives, purchased the grain and then sold the grain, and all farmers received the same price. Brownlee was also Alberta’s chief negotiator in talks with Ottawa to win control of natural resources from the federal government; for most of the decade, these talks with the federal Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King drew out with no resolution, perhaps due to the pressure from the provincial Liberals, who didn’t want to let the UFA walk away with such a major political victory. As Attorney General, Brownlee was also in charge of enforcing prohibition, which became increasingly unpopular in 1922/1923 after the murder of three policemen by bootleggers. Although the UFA supported prohibition, it was forced to admit that it was unenforceable due to rising public opposition, and a plebiscite was held on the issue in 1923. Voters rejected prohibition in favour of the government sale of all liquors.

By 1925, Greenfield was widely seen as weak and indecisive, while UFA MLAs found his reliance on Brownlee to be embarrassing. Many assumed that, led by Greenfield, the UFA would lose the next election; the provincial Liberals had confidently predicted that they would win back power in the next election. In 1924, Brownlee had rejected an offer from rebel MLAs to replace Greenfield as premier, but in November 1925, Brownlee was persuaded by Henry Wise Wood to accept the office if Greenfield was to relinquish it voluntarily. Greenfield had never wanted to be premier, so he gladly stepped aside for Brownlee. An election was held in June 1926, and the UFA was reelected with an increased majority over a poor Liberal and Tory opposition. Of the UFA’s 46 candidates in the province, only three did not win their seats, giving 43 out of 60 seats to the UFA against 7 for the Liberals, 6 for labour candidates and 4 Tories. The UFA won a seat in Edmonton. The election was the first Albertan election fought using a different electoral system – STV in multi-member Calgary and Edmonton, and IRV (optional counting) in the rest of the province.

Brownlee’s first term government was largely successful. The government had tried to divest itself of money-losing railways under Greenfield’s premiership, but attempts to sell them to the Canadian Pacific (CPR) and Canadian National (CN) failed at the time and the railways continued draining the provincial budget. In 1928, after they began showing a profit, Alberta was able to sell the remaining lines to the CPR. The budget situation was also solid: Alberta recorded a surplus in 1925 and 1926. Brownlee’s rigid fiscal conservatism irked radicals in the party, and he was not keen on increased spending on new social programs or on social programs altogether. His ‘scrooge’ reputation would come to hurt his popularity later on.

However, his government also passed the Sexual Sterilization Act of Alberta in 1928, which created the Alberta Eugenics Board, whose role was to review and mandate the sterilization of any mentally disabled psychiatric patient (if there was unanimity among board members and permission of the patient/nearest relative). The law remained in place under Social Credit (which even facilitated its application), and was only repealed by the Conservatives in 1972. Between 1929 and 1972, 4,785 cases were presented to the Alberta Eugenics Board, and 99% of these cases were approved, resulting in the sterilization of 2,832 children and adults in the province. At the time, however, eugenics were supported by progressive moral reformers like early feminist Nellie McClung, socialist leader J.S. Woodsworth and the UFA’s women’s league.

Negotiations with Ottawa over provincial control of natural resources continued; the two sides came close to an agreement in 1926, but Alberta disagreed with Ottawa’s inclusion of an amendment which required the province to continue supporting separate schools, and the issue remained a point of contention which blocked any final agreement until 1929. That year, both King and Brownlee came to an agreement in December 1929. Alberta would receive an annual subsidy in perpetuity, the amount of which would increase as the province’s population grew. The federal-provincial agreement was a major victory for Brownlee, who had succeeded where all his predecessors had failed, and he was hailed as hero in Alberta.

In 1930, despite the onset of the Great Depression, the government was still surfing on the popularity of the resource transfer agreement and the UFA was easily reelected to another majority government – although with a slightly reduced majority, with 39 seats out of 63 (and 47 candidates) against 11 for the Liberals, 6 for the Conservatives and 4 for Dominion Labor.

Brownlee’s second term was characterized by the collapse of the government, the UFA and the rise of a new populist political movement which would replace the UFA as Alberta’s next political dynasty in 1935.

The Great Depression saw wheat prices tumble from $1.78 per bushel in 1929 to $0.45 per bushel by the end of 1930, causing severe economic hardships for most farmers. Banks denied credit to farmers, while Brownlee was unwilling to provide loan guarantees, concerned that such guarantees would encourage lenders to offer loans at high interest rates knowing that the province would repay them if the farmers did not. The government’s cautious measures had some minor successes, but the lack of decisive legislation alienated many farmers. The collapse in prices also bankrupted the Alberta Wheat Pool, which in 1930 was selling wheat at a price well below the $1 per bushel it guaranteed to its farmers. The Alberta Wheat Pool became reliant on provincial support. In the cities, unemployment reached record levels, a situation only exacerbated by farmers’ sons moving to the cities in desperate need of work. Provincial finances deteriorated, and Brownlee adopted severe austerity measures to cut spending – closing all but two of the agricultural colleges, disbanding the provincial police force, shrinking the civil service, cutting government spending and pay cuts for most government employees. The government also increased taxes, and was reluctant to provide relief to unemployed men.

Labour militancy and political radicalism increased during the Depression years, which worried the conservative Brownlee. The socialist Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the forerunner to the modern NDP, was founded in Calgary in 1932. Many UFA members joined the CCF, but Brownlee saw the CCF as dangerously socialist. The UFA base drifted further away from the government: in 1931, Brownlee’s key ally Henry Wise Wood was replaced as UFA president by MP Robert Gardiner, who moved the UFA sharply to the left and was critical of Brownlee. Gardiner advocated for nationalizations, the cancellation of interest payments and concluded that the monetary system had failed.

As if it was not enough, Brownlee was brought down by a sex scandal in 1934. Brownlee was accused of seducing Vivian MacMillan, a family friend and a secretary for Brownlee’s attorney general in 1930 (when the girl was 18) and continuing the affair for 3 years. MacMillan claimed that Brownlee had seduced her and told her that she must have sex with him for his sake and that of his invalid wife, and that she had relented after physical and emotional pressure. Brownlee denied the charges and claimed that he was the victim of a conspiracy by MacMillan, her new would-be fiancé and the provincial Liberals. MacMillan and her father sued the Premier for seduction. In July 1934, despite discrepancies in MacMillan’s story, the jury found that Brownlee had seduced her in 1930 and that both she and her father had suffered damages in the amounts claimed. The presiding judge, however, disagreed and overturned the jury’s verdict. In February 1935, the Alberta Supreme Court appeals division upheld the court’s ruling. However, on appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada, the provincial court’s decision was overturned in March 1937 and the SCC ordered Brownlee to pay $10,000 in damages to MacMillan, plus trial costs. Although Brownlee settled with MacMillan, he sought to clear his name and obtained leave from the federal government to appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, at the time Canada’s highest court of appeal. In March 1940, the committee denied Brownlee’s appeal and endorsed the SCC’s decision.

However, as soon as the jury found that Brownlee had seduced Vivian MacMillan, he recognized that his political career was over and resigned as Premier. He was succeeded on July 10, 1934 by Richard Gavin Reid, the conservative provincial treasurer. Although Reid did take some policy initiatives, the government was very weak. It found itself at odds with the UFA’s membership, and was forced to deal with a serious and dangerous threat: social credit.

Social Credit era (1935-1971)

William “Bible Bill” Aberhart was born in Ontario in 1878 and moved to Calgary in 1910, where he worked as a school principal, a job he held until 1935. He was an able, competent, intelligent and generally respected principal, although he was inflexible and fairly authoritarian. Aberhart was intensely religious, an evangelical Christian who believed in the literal meaning of the Bible. In Calgary, he began preaching at a Baptist church but by 1918 he had established an inter-denominational Bible study group which grew in size. In 1924, Aberhart agreed to do weekly religious radio broadcasts, which carried his voice across the Canadian Prairies and even into the United States. He was a charismatic man, a great story-teller who captivated his listeners. He took little interests in politics until 1932, when he stumbled across the writings of Major C.H. Douglas, a British engineer who had written on the theory of social credit.