Honduras 2017

Presidential, congressional and local elections were held in Honduras on November 26, 2017.

Electoral and political system

Honduras is a presidential republic, much like the other countries in Central or Latin America.

The President of Honduras is directly-elected to a four-year term by simple majority (FPTP), alongside three presidential designates (vice-presidents). Under the 1982 constitution, Honduras had an usually strict and rigid lifetime ban on presidential reelection: not only did article 239 ban anyone who had held the presidency from being president or a presidential designate, it also stated that “any person who violates this provision or advocates its amendment, as well as those that directly or indirectly support him, shall immediately cease to hold their respective offices, and shall be disqualified for ten years from holding any public office” – this ban on reelection was an ‘entrenched clause’ under article 374. In addition, article 42(5) provided for the loss of citizenship (political rights) for “inciting, promoting, or abetting the continuation in office or the reelection of the President of the Republic” and article 330 of the penal code made promoting or executing acts violating this constitutional ban a crime punishable by 6 to 10 years imprisonment.

In April 2015, the constitutional section of the Supreme Court, ruling on a challenge from former president Rafael Callejas and 15 deputies (most from the ruling party), unanimously declared constitutional articles 239 and 42(5) to be ‘inapplicable’ and article 330 of the penal code to be ‘unconstitutional’ for “restricting, diminishing and distorting fundamental rights and guarantees established in the constitution and human rights treaties” (including political rights, freedom of expression etc.). This is therefore the first election in years in which an incumbent president is seeking reelection.

Some readers will undoubtedly remember that a previous president’s alleged attempts to have the constitution amended to allow for presidential election was what led to the controversial 2009 coup removing President Manuel Zelaya from office. Zelaya had not changed the constitution, but merely attempted to hold a non-binding poll on holding a referendum to convene a constituent assembly, which may have considered reelection. Articles 239 and 374 were used as post-hoc justification for the coup by its supporters. Many of the same people who had supported Zelaya’s removal on these grounds in 2009 now support presidential reelection.

The April 2015 decision from the five-member constitutional section of the Supreme Court was very controversial, rejected by all major opposition parties. Regardless of the validity of its legal arguments, its own legality is dubious because one of the five magistrates rescinded his own signature a day later, breaking unanimity and requiring the full court to hear the case. However, the section’s secretary ignored him and Congress rushed to have the decision published in the official journal (which is unusual).

The decision was rendered by magistrates who had been hand-picked by incumbent President Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH) in December 2012, when he was president of Congress, after Congress (under his control) dismissed four of the five members of the constitutional section for having declared a ‘police purification’ law unconstitutional. Congress had no constitutional power to remove members of the Supreme Court, until it granted itself that right in 2013.

The unicameral Congress (Congreso Nacional) has 128 deputies elected for four-year terms by department. The distribution of seats between the 18 departments is, in theory, roughly proportional to their population, with each department electing at least one deputy – but the seat distribution between departments has remained unchanged since 1989. Cortés department (pop. 2.1 million) elects 20 deputies while Francisco Morazán department (pop. 1.5 million) elects 23. Since 2005, deputies are elected by open-list proportional representation with panachage, with each voter having as many votes as there are seats and allowed to split their votes between candidates of different parties. Votes for candidates from the same party are pooled, and seats are first allocated by party using the largest remainder method of proportional representation with a Hare quota. This website explains the electoral system and its history in greater detail.

The unicameral Congress (Congreso Nacional) has 128 deputies elected for four-year terms by department. The distribution of seats between the 18 departments is, in theory, roughly proportional to their population, with each department electing at least one deputy – but the seat distribution between departments has remained unchanged since 1989. Cortés department (pop. 2.1 million) elects 20 deputies while Francisco Morazán department (pop. 1.5 million) elects 23. Since 2005, deputies are elected by open-list proportional representation with panachage, with each voter having as many votes as there are seats and allowed to split their votes between candidates of different parties. Votes for candidates from the same party are pooled, and seats are first allocated by party using the largest remainder method of proportional representation with a Hare quota. This website explains the electoral system and its history in greater detail.

Honduras also renewed its 20 seats in the Central American Parliament (Parlamento Centroamericano, Parlacen). Voters do not vote separately for them, their distribution is based on the results of the presidential vote.

There are 298 mayors (and an equal number of vice-mayors) and 2,092 aldermen (regidores) in the country’s 298 municipalities. Mayors, on a ticket with a vice-mayor, are elected by simple majority (minus one electoral quotient). Aldermen are distributed based on the mayoral vote, using the largest remainder method with a Hare quota. Each municipality has either 4, 6, 8 or 10 aldermen based on their population (i.e. all municipalities with over 80,000 people and departmental capitals elect 10).

According to Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2017, Honduras is a partly free country – with a score of 46 (best = 100), the fourth lowest in all of the America after Cuba, Venezuela and Haiti. The report writes that “institutional weakness, corruption, violence, and impunity undermine its stability” and “journalists, human rights defenders, and political activists face significant threats, including harassment, surveillance, detention, and murder”. Honduras scores very poorly on ‘functioning of government’ and ‘rule of law’, reflecting widespread corruption, a weak, politicized judiciary and police/armed forces corruption and abuses. Many constitutionally guaranteed fundamental rights, including freedoms of assembly, association and the press are not respected and systematically violated by authorities. The press is not free and ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few powerful business elites. Investigative journalists working on corruption or organized crime face threats, intimidation, violence and arbitrary legal decisions.

Honduras’ Supreme Court (Corte Suprema de Justicia) has 15 magistrates elected by Congress (with a two-thirds majority) for seven-year terms, from a list of names chosen by a nominating committee which is supposedly independent and representative (members from the court, the bar, the human rights commissionner, private enterprise, academia, civil society and workers). The judiciary, however, has long been politicized and typically seen by the two traditional parties as something to be partitioned as ‘spoils’ – the usual formula having been to split it equally between the two parties with one extra seat to the governing party (8-7). The nominating committee has been roundly criticized for lacking independence, transparency and professionalism. In January-February 2016, Congress elected a new Supreme Court, with 8 members close to the ruling National Party and 7 members close to the opposition Liberal Party, but because of the greater multi-party dispersion of Congress since 2014, it took five rounds (and, according to some allegations, bribing a few opposition lawmakers). Of the 15 new magistrates, two failed the polygraph test, three are ‘mentally retarded’ (and only 3 have above average intelligence, however they measured that) and only 5 got a score over 50 on an evaluation scale.

Honduran elections are, to a certain extent, free and somewhat fair but often marred by a number of irregularities like vote buying, harassment of international observers by immigration officials, problems with the voter roll (the national registry of persons) and potential fraud in the transmission of local tally sheets. The Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) is often accused of bias towards the ruling party and general incompetence.

Until recently, Honduras had the highest homicide rate in the world (86.5 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011). Since 2011, the homicide rate has consistently fallen, reaching 59.1 in 2016 and projected to fall below 50 in 2017. Nevertheless, along with Venezuela and El Salvador, Honduras still has one of the highest homicide rates in the world.

Historical background: Entrenched elite corruption

Honduras was the original “banana republic” at the turn of the last century, leaving a lasting impact on elite structures and political practices.

In contrast with other Central American countries, Honduras lacked a strong land-owning oligarchy because most of its principal export industries (mining, bananas) were foreign-owned. ‘Traditional’ local landed elites were involved in cattle ranching, coffee, cacao, internal trade and – most importantly – politics. With the increase in cattle exports after World War II and growing pressure for agrarian reform, the traditional elites became more economically and politically active. They have historically controlled Honduras’ two traditional parties – the National Party (Partido Nacional) and Liberal Party (Partido Liberal) – rent-seeking clientelist organizations. Since the 1980s there have been few, if any, ideological differences between the two parties (with the potential exception of the ‘odd’ Manuel Zelaya). In the 1990s, both National and Liberal presidents implemented neoliberal economic reforms – sponsored by the IMF and the United States – including trade liberalization, privatization and reducing government expenditures. Politics have been about access to patronage and the other spoils of powers, with little regards for the formal constitutional rules (as repeatedly evidenced since 2009), and the state has always been seen as a source of legal and physical protection for the elites. With the decline in traditional exports since liberalization the 1990s, self-enrichment through public resources and contracts has become key to their power and wealth. The last three presidents have come from the ‘traditional elite’ – Manuel Zelaya (2005-2009) and Porfirio ‘Pepe’ Lobo (2010-2014) were cattle ranchers from Olancho department in eastern Honduras, while incumbent president Juan Orlando Hernández is from a coffee family in the interior western department of Lempira.

The traditional elite shares power with newer ‘transnational elites’ (term used by InsightCrime’s report on elites and organized crime in Honduras) – a small economic elite of European or Middle Eastern (Levantine) origin (locally known as los turcos or ‘the Turks’) – families like the Facussés, Rosenthals, Canahuatis, Nassers and the Kafies. They have established control over most of the modern private sector in the country (the prime beneficiaries of neoliberal economic reforms) – banking, media, telecommunications, agro-industry, retail, maquiladoras, food services and tourism. They also became active in politics. Liberal president Carlos Flores (1998-2002) was the nephew of the late business magnate Miguel Facussé. Yani Rosenthal, who recently pleaded guilty to money laundering charges in US federal court, was minister of the presidency under President Manuel Zelaya; his father, Jaime Rosenthal, was a prominent Liberal politician (vice president 1986-1989) and businessman.

Up until the mid-twentieth century, the military served as the instruments of caudillos in civil wars and coups (and, like elsewhere in Latin America, most leading political leaders were military men). During Tiburcio Carías Andino’s 16-year dictatorship (1933-1949), the military was professionalized and institutionalized – and began acting as such. A 1956 military coup was the first in a series of coups (1963, 1972, and ‘internal coups’ in 1975 and 1978) and the military ruled the country directly, with only a single interruption, between 1963 and 1982. During this period, the military became an independent elite in its own right, controlling key sectors of the state (customs, airports etc.) and building a vast business empire (airlines, telecommunications, cement, food retailing, banking etc.). In power, the military worked with the traditional political elites in the National Party (the Liberal Party, until 1980, was perceived as anti-militarist), giving rise to a new ‘hybrid elite‘ – politicians connected to the military, officers becoming business tycoons and financial partners, military children married with the children of the traditional elites. After 1980, the military oversaw a controlled transition to civilian rule, which culminated in the election of Roberto Suazo Córdova, a Liberal, to the presidency in 1982.

This democratic transition, however, coincided with the overthrow of the Somoza regime by the Sandinistas in Nicaragua (1979) and the beginning of the civil war in El Salvador. Honduras became a strategic platform for US interests in Central America in the 1980s. US military aid to Honduras increased from $3.3 million to $31.3 between 1980 and 1982 and totalled $333 million in the 1980s. Honduras became the base of operations for the Nicaraguan Contras, trained and supplied by the US military and the CIA. Even after the democratic transition, defence (and, by extension, foreign policy) remained under military control, commanded by Brigadier General Gustavo Álvarez Martínez between 1982 and his ouster by a clique of rival senior officers in March 1984. Álvarez Martínez, educated in Argentina and the School of the Americas, was a hardliner who supported US policy in Central America and declared the country to be in a “war to the death” against Nicaragua. Álvarez Martínez chaired the Asociación para el Progreso de Honduras (Aproh), a quasi-fascist organization which included prominent conservative businessmen and politicians (its vice president was Miguel Facussé). Álvarez Martínez was ousted as commander of the armed forces by rival officers in 1984, who opposed his moves to streamline the military hierarchy and his close ties to the US.

Since the days of the military regime in the 1970s, senior officers have been implicated in criminal activities (drug trafficking) and enjoyed close ties to leading criminals, most notably Juan Ramón Matta Ballesteros, a major Honduran drug trafficker arrested in 1988. Matta Ballesteros connected the Medellín cartel (Colombia) and Mexican drug cartels (Guadalajara cartels and others) and had close connections to senior officers in the Honduran army, including Colonel Leónidas Torres Arias, the former head of military intelligence (who connected him to Panama’s Manuel Noriega). During the 1980s, Matta Ballesteros’ fleet of planes carried American weapons and supplies south to the Contras and returned north with drug shipments for his Mexican partners – and the CIA and DEA turned a blind eye to Matta Ballesteros and the Honduran military’s activities as long as Honduras remained useful to US security objectives in Central America. He built a billion-dollar business empire, gained a large popular following and rubbed shoulders with the elite. His luck ran out and connections faltered in the late 1980s, accused by the US of the murder of a DEA agent, and he was abducted by Honduran and American authorities in Tegucigalpa in 1988 and sent to the US via the Dominican Republic. His arrest led to massive anti-American protests in Tegucigalpa, during which an annex of the US embassy was burned down.

The military’s overt power declined with the end of the Central American conflicts and US involvement. The military lost its businesses and state agencies, and a civilian police force was finally reestablished in the 1990s. Nevertheless, retired officers and their families have remained powerful as a bureaucratic elite and the military – reframed as Honduras’ premier crime-fighting force, has regained in power and political influence under the National Party administrations since 2010, particularly under incumbent president Juan Orlando Hernández.

Honduras is a major drug transit country between South America and Mexico/the United States. Drug shipments are handled by foreign (Mexican, Colombian) criminal groups or local ‘transporters’ – groups like the Cachiros, the Valle Valle and Handal Pérez families. Honduras is not only a major hub for drug trafficking, but also for arms trafficking and other, less lucrative, criminal activities – drug dealing, extortion, kidnapping, human smuggling. Economic changes, destruction caused by Hurricane Mitch, deportations from the US and realignments in drug trade dynamics led to a crime boom in Honduras beginning in the late 1990s, worsening in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Criminal organizations, particularly the foreign drug cartels and local drug traffickers/transporters, do not stand on their own in a separate sphere. They have strong ties to security forces and the political and economic elites. In exchange for safe passage of their merchandise and money laundering, they fund candidates and develop close ties to politicians.

Ties between criminals and elites are perhaps most obvious at the local level, but it extends to national politics. José Miguel ‘Chepe’ Handal Pérez, arrested in 2015 and accused of coordinating drug shipments for the Sinaloa Cartel and Los Zetas, was an aspiring Liberal politician and his brother, Esteban Handal, was defeated in the 2000 and 2010 Liberal presidential primaries. Even more explosively, former president Pepe Lobo’s son Fabio was arrested in 2015 and recently sentenced to 24 years in US prison for conspiring to import cocaine into the US. Lobo used his father’s position to connect drug traffickers to corrupt police and government officials. During Fabio Lobo’s trial, Devis Leonel Rivera Maradiaga – one of the leaders of the Cachiros – claimed that he had given up to $300,000 to Pepe Lobo’s 2009 presidential campaign in exchange for ‘protection’, public contracts and non-extradition. He also said that he had bribed Tony Hernández, the president’s brother, in return for settling debts owed to a Cachiros-owned company which had done roadwork for the government.

Recent background: Honduras since 2005

Manuel Zelaya and the 2009 coup

Liberal candidate Manuel Zelaya, a cattle rancher from Olancho department, narrowly defeated Pepe Lobo Sosa in the 2005 presidential elections. At the time, there appeared to be few ideological between the two candidates. However, Zelaya, in spite of his elite background, turned out to be ‘rogue element’. In a departure from the hardline anti-crime approach of his Nationalist predecessor, Zelaya supported the rehabilitation of violent offenders – although during his presidency, the homicide rate increased from 37 (2005) to 66.8 (2009). A populist who ‘shifted left’ and grew increasingly close to Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, Zelaya increased the minimum wage by over 60%, expanded social programs (aid to the poor, free schooling), opened investigations into land disputes between farmers and palm oil producers (including Miguel Facussé’s Dinant corporation) in the Bajo Aguán valley and overhauled fuel sourcing and distribution (seeking cheaper fuel from Venezuela). In 2008, Honduras joined ALBA, the alliance of leftist countries spearheaded by Venezuela and its allies (Nicaragua, Bolivia, Ecuador).

Liberal candidate Manuel Zelaya, a cattle rancher from Olancho department, narrowly defeated Pepe Lobo Sosa in the 2005 presidential elections. At the time, there appeared to be few ideological between the two candidates. However, Zelaya, in spite of his elite background, turned out to be ‘rogue element’. In a departure from the hardline anti-crime approach of his Nationalist predecessor, Zelaya supported the rehabilitation of violent offenders – although during his presidency, the homicide rate increased from 37 (2005) to 66.8 (2009). A populist who ‘shifted left’ and grew increasingly close to Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, Zelaya increased the minimum wage by over 60%, expanded social programs (aid to the poor, free schooling), opened investigations into land disputes between farmers and palm oil producers (including Miguel Facussé’s Dinant corporation) in the Bajo Aguán valley and overhauled fuel sourcing and distribution (seeking cheaper fuel from Venezuela). In 2008, Honduras joined ALBA, the alliance of leftist countries spearheaded by Venezuela and its allies (Nicaragua, Bolivia, Ecuador).

In a leaked US diplomatic cable from then-US ambassador Charles A. Ford, Zelaya is described as a “rebellious teenager, anxious to show his lack of respect for authority figures” whose “principal goal in office is to enrich himself and his family while leaving a public legacy as a martyr who tried to do good but was thwarted at every turn by powerful, unnamed interests”. His behaviour is described as ‘erratic’, deliberately stirring “street action in protest against his own government policy – only to resolve the issue at the last moment”. It is also claimed that Zelaya has “no real friends outside of his family, as he ridicules publicly those closest to him”. The cable also details corruption in Zelaya’s government, the most prominent case being his nephew Marcelo Chimirri, appointed head of Hondutel (the state-owned telecom company, plagued by corruption, debt and mismanagement). The cable reported that Chimirri is “widely believed to be a murderer, rapist and thief”; he was recently sentenced to 9 years in jail for illicit enrichment. The cable, without much substantiation, states that “Zelaya’s inability to name a Vice Minister for Security lends credibility to those who suggest that narco traffickers have pressured him to name one of their own to this position” and notes “his close association with persons believed to be involved with international organized crime”. Far more seriously, ambassador Ford said that he was “unable to brief Zelaya on sensitive law enforcement and counter-narcotics actions due my concern that this would put the lives of U.S. officials in jeopardy”.

Zelaya repeatedly clashed with the traditional media – which, in Honduras, is controlled by the ‘transnational elites’ (La Tribuna by former president Carlos Flores, Tiempo by Jaime Rosenthal, La Prensa and El Heraldo by the Canahuatis) – which he accused of bias, and responded chavista-style by imposing mandatory two-hour government broadcasts. He also clashed with his own party in Congress (and the president of Congress, Roberto Micheletti) and his first vice president, Elvin Santos, distanced himself from him before going on to win the Liberal Party’s 2008 presidential primary.

In March 2009, Zelaya announced his intention to hold a plebiscite on June 28 on whether to organize a referendum convening a constituent assembly alongside the November 2009 general elections – the so-called fourth urn (cuarta urna). This idea was opposed by Micheletti, and challenged in court by the attorney general. In late May, an administrative court ruled that Zelaya’s plebiscite was illegal, a decision upheld on appeal. Despite the ruling, Zelaya pressed forward, although at the last minute he reformulated his plebiscite as a non-binding ‘opinion poll’. The constitution does not provide for any way to call a constituent assembly (although that’s never stopped anyone), and it may only be amended with a two-thirds majority in two consecutive congressional sessions. The constitution does allow for the president to call referendums and plebiscites, subject to congressional approval (article 5).

In the final days before the scheduled June 28 poll, tensions between Zelaya and his opponents escalated amid growing anti-Zelaya protests in the streets. On June 24, Zelaya fired General Romeo Vásquez Velásquez, the commander of the armed forces, for refusing to provide logistical support for the poll. The defence minister and the chiefs of all three branches of the military resigned in solidarity. The next day, as ballots printed in Venezuela landed in Tegucigalpa (collected by Zelaya’s men before the attorney general could seize them), the Supreme Court ordered general Vásquez’s immediate reinstatement and the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) declared the poll illegal. Unable to reach any compromise with the presidency, Congress turned firmly against Zelaya, setting up a commission to look into illegal actions committed by the president (but failing to provide proof for its allegations). On June 26, the Supreme Court issued a sealed arrest warrant against Zelaya, accusing him – among others – of treason and abuse of power.

On the early morning of June 28, soldiers stormed the presidential palace, arrested Zelaya and jetted him off to Costa Rica (in violation of several constitutional rights). Congress ‘obtained’ a forged/fake resignation letter, removed Zelaya from office and declared Roberto Micheletti as president for the remainder of Zelaya’s term (which ended in January 2010). The Supreme Court supported Zelaya’s ouster, and two days later the Public Ministry formally filed 18 criminal charges against Zelaya, vowing to arrest him if he returned to Honduras (as he was conspiring to do from Costa Rica). Zelaya’s opponents claimed that his removal from office was justified because the June 28 poll would have automatically convened a constituent assembly (false) and/or Zelaya would have used an hypothetical constituent assembly to allow reelection (a supposition, although Zelaya on June 25 had publicly declared that “re-election is a topic of the next National Constitutional Assembly”). The famous article 239 (see above) was, however, used a justification for the coup only after the fact. Others claimed that Zelaya automatically ceased to be president as soon as he issued the illegal decrees, although nowhere does the constitution provide for that. In any case, even if a constituent assembly had been convened in a November 2009 vote, Zelaya would have been ineligible for immediate reelection because his term ended in January 2010. To claim that he would have done away with this and extended his term in office unconstitutionally is an assumption which can hardly be proven.

In a July 24, 2009 cable, the US ambassador (Hugo Llorens) summarized the events: “the military, Supreme Court and National Congress conspired on June 28 in what constituted an illegal and unconstitutional coup against the Executive Branch, while accepting that there may be a prima facie case that Zelaya may have committed illegalities and may have even violated the constitution”, considering Micheletti’s accession to the presidency to be illegitimate. The cable concluded that neither the military or Congress had the right to remove the president, something which at the time could only be done by the Supreme Court after indictment, trial and conviction. It also argued that the article 239 arguments against Zelaya were flawed on multiple grounds. Beyond the legality of the events, however, there was clearly near-unanimity among institutions and the elites for Zelaya’s ouster: the Congress, Supreme Court, TSE, attorney general, the Catholic cardinal, lower courts and both major political parties.

There were several pro and anti-Zelaya protests in Honduras after the coup. The new government imposed a curfew, temporarily suspended civil liberties, censored and restricted media coverage, arbitrarily arrested protesters and – according to several reports – harassed journalists (including foreign correspondents from Venezuela) and arbitrarily detained three foreign ambassadors (Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela). An Amnesty International report from August 2009 reported excessive use of force (police brutality), gender-based violence and attacks against human rights defenders and journalists.

The Honduran coup was quickly condemned by nearly the entire regional and international community, including the US which also considered it a coup. Honduras was suspended from the OAS and most Latin American countries and EU member-states recalled their ambassadors. Micheletti’s unrecognized regime became stubbornly isolationist, effectively telling the international community to mind their own business. The United States supported Zelaya’s reinstatement and suspended aid to Honduras in July, but Secretary of State Hillary Clinton soon became more interested in settling the crisis by supporting the scheduled November elections rather than pressing for Zelaya’s reinstatement (as most Latin American states did). Clinton’s murky role in the Honduran crisis came back to haunt her during the 2016 Democratic primaries. In a 2016 interview, she claimed that the Congress and judiciary had actually followed the law in removing Zelaya (which is false) and defended her decision not to call the coup a military coup (because it would have suspended aid).

In July, talks between Zelaya and Micheletti mediated by Costa Rican president Óscar Arias failed in large part because the two sides held mutually exclusive views on the key question: Zelaya wanted to be reinstated, Micheletti refused to go and let Zelaya return. In October, both sides, in principle, agreed on a US-brokered agreement which was to let Congress decide whether or not to reinstate Zelaya – Congress, unsurprisingly, voted against and Zelaya had already demurred from the deal. Elections were held, on schedule, in late November 2009. National Party candidate Porfirio ‘Pepe’ Lobo, a former president of Congress (2002-2006) and 2005 presidential candidate, was elected with 56% of the vote against 38% for Liberal candidate Elvin Santos (Zelaya’s former first vice president, who had distanced himself from the deposed president). Elvin Santos was badly hurt by the coup, trying to claim a seemingly non-existent middle ground with a non-committal stance. Boycotted by Zelaya, turnout was 50%, about 6% less than in 2005.

The elections did, in fact, ‘end’ the crisis (as far as the rest of the world was concerned) and Lobo’s inauguration in January 2010 made the Zelaya case moot. The US, despite earlier statements, quickly recognized the elections and resumed close relations with Tegucigalpa. Most Latin American countries, led by Costa Rica and right-wing Panama and Colombia, also began recognizing the results of the election. Brazil, which had strongly supported Zelaya and given him refuge at their embassy in Tegucigalpa after September 2009, told him to move out by January 2010 and recognized the new government. Zelaya, following an agreement with Lobo, was allowed to go to the Dominican Republic. Only the ALBA states (plus Paraguay and Uruguay) did not recognize the election. In 2011, an agreement between Zelaya and Lobo allowed Zelaya to return home.

National Party in power since 2010

Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH), a shrewd political operator and Nationalist congressman from Lempira department, became president of Congress under Lobo’s presidency. The presidency of the Honduran Congress is the most powerful legislative position (controlling debates, special commissions etc.) and is a stepping stone to the presidency of the Republic. As president of Congress, JOH was behind the adoption of several important laws and controversial decisions – one of which, the illegal December 2012 purge of the constitutional section of the Supreme Court, was discussed above. Several of the laws passed while JOH was president of Congress have favoured the activities of the country’s political and business elites.

JOH manoeuvred his way to the Nationalist nomination in 2012 against Tegucigalpa mayor Ricardo Álvarez (who became his first vice president). He campaigned on a demagogic, populist and hardline anti-crime platform – promising a ‘soldier on every street’ and a slew of populist promises (CCTs, 800,000 jobs, some gimmicky home renovation program marketed like Extreme Makeover Home Edition, and even a discount card with the party’s logo). He was elected president in November 2013, winning 36.9% of the vote against 28.8% for Xiomara Castro, the wife of former president Manuel Zelaya and the candidate of Zelaya’s new left-wing party, Libertad y Refundación (Libre). Mauricio Villeda, the right-wing candidate of the Liberal Party (from Carlos Flores’ faction), won 20.3%. A fourth candidate, melodramatic former TV presenter and sports commentator Salvador Nasralla of the new right-wing populist Anti-Corruption Party (PAC), won 13.4% of the vote – performing very well in San Pedro Sula, the country’s economic capital. The elections marked the collapse of the old two-party system and the new Congress reflected the new multi-party system: 48 Nationalists, 37 Libre, 27 Liberals, 13 PAC and 3 from the three old minor parties (left-wing UD, centre-right Christian Democrats, centre-left PINU).

Pepe Lobo and JOH’s administrations have their differences, particularly in terms of outcomes, but it makes sense to discuss them together. Much of the information below is drawn from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s excellent report, When Corruption is the Operating System. One passage stood out for me:

“‘I have to have someone to manage the state,’” a Latin American official working in Tegucigalpa represented the elite’s viewpoint. “‘You do it in my service. You’re there to guarantee our businesses. In return, you can steal as much as you want.’” Or, in the words of another highly placed interviewee, “The politicians are at the service of the economic elite. When the president tries to be a real president and doesn’t obey the ten families, you get a coup d’état.”

‘Open for business’ – or open for crony capitalism?

A public-private partnership law (2010) allows businessmen to carry out public contracts under flexible (non-transparent) arrangements, potentially allowing for embezzlement or diversion of public funds. Pepe Lobo and his foreign minister, Mario Canahuati (from a Levantine elite family and former president of COHEP, the private business council), advertised that Honduras was “open for business” and aggressively sought to attract foreign investment.

Coalianza, a commission to promote public-private partnerships, was created in 2010. It choose projects, coordinates any public bidding process (which are non-transparent) and enters into contracts. Coalianza projects are under a cloud of secrecy: they have not been audited and it is unclear if they fit under the national budget. It certainly doesn’t help that Honduras’ independent audit bodies, like the Superior Tribunal of Accounts or the banking regulatory commission, have been weakened or lost in their independence vis-a-vis the executive.

An even more famous and controversial piece of Pepe Lobo and JOH’s “open for business” agenda are the “model cities” (or charter cities), officially known as ZEDE. Trying to emulate Singapore or Hong Kong, these model cities go even further than traditional free trade zones – allowed to establish their own laws (under Honduran sovereignty and partial application of certain constitutional rights), tax systems and judiciaries. The original model cities law (RED), brainchild of American economist Paul Romer, was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in October 2012 amidst concerns of creating ‘states within the states’ and the loss of national sovereignty.

However, Congress reworked the law a bit and a new law creating the ’employment and economic development zones’ (ZEDE) in 2013. The new law makes clear that the ZEDE are part of Honduras and subject to the state for ‘sovereignty, application of justice, territory, national defence, foreign relations, elections and issuance of identity documents and passports’, although only 6 articles of the constitution’s 379 fully apply to the ZEDE. The ZEDE have, according to the official website, autonomy with their own political, administrative, economic and judicial system. They are overseen by a 21-member ‘committee for the application of best practices’, which appoints individual ZEDE on-site administrators and proposes names for the ZEDE’s judiciaries (appointed by the Honduran judicial system). The rest of the law is intentionally vague, only providing a framework for the creation of low-tax, free market zones where those in charge will have ample leeway to create their own political, economic, fiscal, judicial, security and even educational systems. ZEDEs may be as small or as big as their promoters want them to be; they need to be approved by Congress, although only ZEDE in high-density areas require popular consent through a referendum. There are significant concerns about the imposition of ZEDEs in low-density regions, especially areas with large indigenous or Garifuna populations.

An August 2017 article in The Economist discusses these model cities, which have excited North American libertarians and conservatives. They are still slow to get off the ground, but enjoy political support in Honduras (and foreign libertarians and private businesses are still interested). The ‘committee for the application of best practices’ originally included the likes of Grover Norquist, Mark Klugmann (former speechwriter for Reagan and Bush 41), Richard Rahn (then at the Cato Institute) and Michael Reagan. The Economist said it met just once in 2015, and that it has been reduced down to 12 members (including Rahn and Austrian economist Barbara Kolm, a former FPÖ politician).

State-owned enterprises like Hondutel and the National Electrical Energy Enterprise (ENEE) have been wracked by corruption, mismanagement and debts. ENEE’s financial situation has improved since 2014, although largely due to PPPs, falling oil prices and layoffs. Since the 1990s, ENEE has given sweetheart contracts to private sector electricity generators – including, since 2007, renewable energy generators (given locked-in tax breaks and exemptions, a 10% premium over market rates, annual increases on these higher prices; the state is mandated by law to buy all renewable energy they produce etc.). The beneficiaries of these fossil fuel and renewable energy contracts have been the ‘transnational elite’ families – Facussés, Kafies, Nassers. Following IMF recommendations, Honduras is trying to slowly privatize ENEE.

The Honduran government, with international funding, has pushed forward on highly controversial hydroelectric dams which threaten local environments and their communities. One of these is Patuca III (in Olancho department), already well underway since 2015 in association with Sinohydro (a Chinese state-owned company) and financed with a loan from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. The government has pressed forward with this project, riding roughshod over local and foreign opposition, in spite of an Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) letter very critical of Honduras’ weak environmental assessment and the lack of proper consultation with local communities. The dam will have a significant impact on ecosystems and communities downstream, where residents fear that the river will get lower, affecting navigation and their livelihoods. Beyond the effect on the river’s ecosystems and endangered species, work on the dam has already caused deforestation. Any ‘consent’ was obtained by deceit. ENEE advertises Patuca III as a ‘clean energy’ project, hoping to get carbon credit and generate income by exporting power through the integrated Central American electricity market (SIEPAC).

The most infamous of these hydroelectric projects is the now-halted Agua Zarca dam on the Gualcarque river in Intibucá department. The project was launched by DESA, an Honduran company created solely for the Agua Zarca in 2008 and with ties to both public and private sector elites. The project has been strongly opposed by local Lenca communities, organized by the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH). DESA’s local consultations were superficial at best and obtained approval from the local mayor by bribing him. With an engineering contract with Sinohydro and financing from Finnfund (Finland’s development finance company) and FMO (the Netherlands), work began in 2011. Agua Zarca faced massive organized local resistance in 2013. In July 2013, the military – protecting the site – opened fire on unarmed peaceful protesters, killing one indigenous leaders and wounding several others. Mounting local opposition prompted Sinohydro to terminate its involvement, but other outside investors stayed put and DESA moved construction to the opposite side of the river without informing anyone.

Berta Cáceres, a Lenca community leader and environmental activist in Intibucá who co-founded COPINH in the 1990s, was one of the most prominent opponents of Agua Zarca and an internationally-recognized community leaders (awarded several prizes for her work). Cáceres and other opponents of the projects had faced intimidation, physical violence, criminal charges and death threats from the beginning. In March 2016, Cáceres was assassinated at her home. Cáceres’ murder drew international attention and immediate condemnation/indignation from abroad. Yet, the initial official response to her death was shockingly poor: the first arrest made in relation to the case was of a COPINH member, while the sole witness (a Mexican friend of Cáceres) was kept for interminable questioning. Authorities, it seemed, didn’t care about investigating the repeated death threats she had faced. Finally, in May 2016, the government arrested four men including DESA’s manager for social and environmental affairs, two military men and a former security employee. The military is deeply implicated in Cáceres’ murder: in 2016, a former soldier later admitted that Cáceres’ name was on a military hit-list; three of the eight suspects in custody are military or ex-military, two of them were trained at Fort Benning, GA (former School of the Americas) and one was also a trainer for the Honduran military police PMOP. Despite these arrests, the Honduran government has been criticized for being very slow to actually prosecute those responsible (including the intellectual authors). Given widespread international condemnation, Finnfund and FMO formalized their withdrawal from the project in 2017.

As detailed in the Carnegie Endowment’s report, hydroelectric dams are not the only economic development projects sparking local protests and resistance. Since the 1990s, there have been violent conflicts between cooperatives/campesinos and palm oil agro-industrialists (predominantly Miguel Facussé’s Dinant Corp.) in the Bajo Aguán valley (Colón department, in the northern Caribbean region). A 1992 agricultural modernization law allowed for previously inalienable land cooperatives (formed during an early agrarian reform in the 1960s) to be parcelled out into small plots which could be sold to private landowners – a law which has, in practice, greatly favoured the interests of powerful landowners, particularly the ‘transnational elites’ in the lucrative palm oil industry. As in Colombia, the expansion of African palm oil has been accompanied with major human rights violations and a certain proximity between agro-industrialists and organized crime.

Unsurprisingly in this context, the environment ministry has been deliberately debilitated, obediently rubber-stamping the government’s proposed development projects – often without conducting a thorough environmental impact assessment.

The government has vaunted its economic and fiscal achievements. With improved tax collection, reforms in the parastatals (ENEE, Hondutel), a 2013 tax reform and austerity measures, Honduras’ deficit fell from 7.9% of GDP in 2013 to 2.6% of GDP in 2016. In December 2014, Honduras obtained a $189 million loan over three years from the IMF, in exchange for ‘fiscal consolidation’ and ‘structural reforms’. As the government likes to boast, Honduras has gotten positive reviews from credit rating agencies – Moody’s upgraded the country’s rating from B1 to B2 (and before that from B2 to B3) while Standard and Poor’s has maintained it at B+ with a positive outlook. FDI inflows reached $1.4 billion in 2014, although it fell to $1 billion in 2016.

The government claims to have created 594,000 ‘jobs and opportunities’ in three years (2014-2016). Honduras has enjoyed strong economic growth in recent years: 4% in 2017, compared to 3.1% in 2014 and 2.8% in 2013. The government’s glossy 2014-2016 ‘achievements’ brochure boasts of its achievements in attracting FDI, restoring Honduras’ credibility on global markets, fiscal responsibility, security and job creation (among other areas) and ambitiously claims that Honduras will become the “logistical centre of the Americas” by 2020, with a new international airport, six development and tourism ‘corridors, three ports, ‘attractive tax regimes’ and free trade zones/ZEDEs.

Noticeably absent from the government’s self-congratulations is any mention of poverty. Honduras is one of the most unequal countries in Latin America (Gini coefficient 50.1) and has a persistently high poverty rate. In 2016, 65.7% of the population lived in poor households (42.5% in extreme poverty and 23.2% in relative poverty), nearly unchanged from 2010 (66.2%). Poverty increased between 2010 and 2012 (reaching 71%) and has fallen since 2015 (68% to 66%). Vida Mejor is the government’s flagship anti-poverty social development project – including a broad array of programs like the Bono Vida Mejor (cash transfers to poor families with children enrolled in school) and various social housing and education projects. According to the presidency’s data, over 515,000 people have benefited from the Bono Vida Mejor and thousands have benefited from other programs under the Vida Mejor label. Critics claim that the Bono Vida Mejor, de facto managed directly by the presidency (and marketed as a presidential project), is a clientelist scheme distributed to party supporters or that its funds are being used for partisan purposes. The program and the Secretariat of Development and Social Inclusion are relatively underfunded and have yet to make a significant (lasting) dent in the poverty rate.

Militarization and crime

To face the crime wave, Pepe Lobo and JOH’s administrations have militarized the police and deployed the armed forces to fight crime. The armed forces, in decline in the 1990s, have regained some of their previous strength under JOH. One rationale for the deployment of the military is that the National Police is deeply corrupt, with police at every level infiltrated by organized crime (including street gangs) and implicated in extra-judicial assassinations. In 2009, top drug czar Julián Arístides González Irías was killed, with police, politicians and drug traffickers implicated. The police, serving the interests of political and economic elites, has been repeatedly accused of harassing people opposed to government policies – including its economic agenda. At a more basic level, police demand bribes and, through involvement with gangs like MS-13, are said to be involved in extortion in the barrios. In response to police corruption, Pepe Lobo’s government passed a police depuration law – which was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2012 for violating officers’ rights to due process. JOH created a police reform commission in 2016, which has been controversial and the subject of some criticism, but may also have helped reduce homicide rates. Since 2016, it has dismissed over 4,400 officers – although most for restructuring, death, mandatory or voluntary retirement.

The military has seen its role and powers expand greatly since 2010, going far beyond ‘national defence’ to encompass maintenance of public order, fighting crime, patrolling indigenous communities, protection of land or development projects and suppressing protests against government economic development policies. Setting the clock back to the 1980s, a military police force (PMOP) was created in 2013 and charged with maintaining public order against organized crime and drug traffickers. According to critics, PMOP is at the personal service of the president and arbitrarily imposes its will through fear. In addition to PMOP, JOH as president of Congress oversaw the creation of other crime-fighting elite unites – TIGRES, ostensibly under the security rather than defence ministry, and FUSINA – an inter-agency task force mixing military, PMOP and TIGRES.

JOH has centralized national security decision-making into a single National Defence and Security Council, which mixes all three branches of government (president, president of Congress, president of the Supreme Court, defence and security ministers) and the attorney general. It has broad powers over security, defence and intelligence matters, and its activities are shielded from public scrutiny by a broadly-worded 2014 secrecy law. Hernández has also surrounded himself with top ‘securocrats’, including his brother, retired colonel Amílcar Hernández (now head of the national anti-extortion force). Retired General Julián Pacheco, the former head of military intelligence, was appointed security minister (police) in January 2015 while still in active service (he resigned his commission to take his cabinet post). Óscar Álvarez, a former US-trained special forces office, served as security minister in 2002 and 2010 and is now a prominent Nationalist congressman.

Despite all the criticism which the militarization of public safety and the state has elicited, even JOH’s critics admit that he has reduced drug trafficking and violence. As noted in the introduction, the homicide rate in Honduras has dropped from 79 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2013 (85.5 in 2012 and 86.5 in 2011) to 59.1 in 2016, projected to fall below 50 in 2017 – perhaps its lowest level since 2006 (46.2). InSight Crime offered seven explanations for the decline in murders: a new anti crime policy focus (anti-gang, extortions), dismantling large criminal structures (Cachiros, Valle Valle), the police reform and purge, prison reform and modernization (2 new max security prisons, and closing San Pedro Sula’s infamously criminally-run prison), increased spending on security and justice, better training and recent penal code amendments, and lastly joint work between the state and civil society. Others, however, claim that JOH has been pressured into going after organized crime and drug trafficking by the United States. Shortly after JOH took office, the Honduran government began extraditing top drug lords to the United States: Carlos ‘El Negro’ Lobo in May 2014, Juving Alexander Suazo Peralta in October 2014 and two of the Valle Valle brothers in December 2014. In 2012, the Congress had adopted a constitutional amendment allowing extradition for cases of drug trafficking, terrorism and organized crime.

The government’s glossy achievements brochure reports that, between 2014 and 2016, over 4,000 new police officers were recruited and 18 criminals extradited. FUSINA arrested over 35,600 people, destroyed 10 drug laboratories and 138 landing strips and decommissioned over 8,000 firearms. In 2016 alone, the government reports, the police and armed forces arrested 20,400 delinquents.

The Carnegie Endowment’s report offered a far more sinister and cynical explanation for JOH’s tough hand against the drug cartels:

Geography may play a role in the more intensive counternarcotics enforcement under Hernández for the simple reason that he grew up in the mountainous southwestern part of the country, which is not the most convenient transshipment zone. Conversely, many of the human rights violations that are sparking social conflicts under Hernández are taking place precisely in his native region.

Zelaya and Lobo, by contrast, hailed from contiguous departments in the east, Olancho primarily, as well as Colón, which anchor the eastern end of narcotics trafficking routes through Honduras. And both apparently became entwined with local cartels, seeming to affiliate primarily with the Sarmientos and Cachiros respectively.

It may be that Hernández’s willingness to crack down on this lucrative trade—despite his close political collaboration with Lobo over the years—derives in part from his lack of opportunity to become engaged in it himself. It was taking place too far from his home base. (p. 80-1)

The US has been the key external player in Honduran defence and security policies for decades. Its involvement has increased under Hernández, who is strongly pro-US and has closely supported all US policies related to Honduras. US funding for the Honduran military and police – mostly counter-narcotics – reached $22 million in 2015 and $17 million in 2017. Overall, according to USAID’s website, US foreign aid to Honduras in 2016 from all US government agencies totalled $127.5 million in 2016 (estimated to fall to $90 million in 2017), most of it (86%) classified as ‘economic’ aid and from the US Agency for International Development.

Corruption

As you can guess from the above, corruption is an entrenched part of politics and economics in Honduras. The country scores just 30 on Transparency International’s 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking 123rd in the world out of 176 (tied with Mexico) – although neighbouring Guatemala and Nicaragua rank even lower.

The most outrageous corruption scandal of JOH’s term involved the Honduran Social Security Institute (IHSS), the public healthcare provider and pensions administration. 7 billion lempiras ($296.8 million) in public money were embezzled – and part of that money (at least 3 million lempiras), by the president’s own admission, found its way to the Nationalist presidential campaign in 2013. To make matters worse, 3,000 people may have died from ingesting fake medicine or due to shortages. The first revelations of the IHSS scandal were publicized by the National Anti-Corruption Council and Public Ministry in 2014. Perhaps up to 60-70% of the IHSS’ operating budget was embezzled through shell companies using various stratagems (procurement fraud, fake contracts with no goods or services delivered, inflated and unjustified purchases, buying placebos). Several politicians and senior public officials including IHSS’ director general, chief of purchases and treasurer were implicated. A drug company founded by the vice president of Congress Lena Gutiérrez (National), her father and two of her brothers sold fake medicine and charged inflated prices for other supplies; she was arrested in 2015. Some members of the ‘transnational elite’ have also been embroiled, like Shukri Kafie.

According to the Carnegie Endowment’s report:

This case illustrates the rough division of labor or territory that characterizes the Honduran kleptocratic network, with most of the outright looting of government coffers perpetrated by public-sector members, often via private companies in the hands of relatives or immediate proxies. In general, companies that win public procurement contracts from government agencies like the IHSS tend not to belong to members of the self-contained, Levantine-descended business elite (p. 49)

The eruption of the IHSS scandal in 2015 led to major protests in Honduras (and among the Honduran emigrant population in the US) demanding JOH’s resignation and the creation of an Honduran version of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), whose remarkable work against corruption in Guatemala led to the resignation of the country’s president and vice president in 2015. Relenting, the government of Honduras allowed for the creation of a ‘support mission against corruption and impunity in Honduras’ (MACCIH) which, unlike CICIG, cannot bring corruption cases forward itself but may support Honduran authorities and help design institutional reforms.

The main thesis of the Carnegie Endowment’s report is that corruption in Honduras isn’t a series of isolated, unrelated stand-alone cases but rather part of an “integrated kleptocratic network”, “the operating system of sophisticated networks that link together public and private sectors and out-and-out criminals and whose main objective is maximizing returns for network members”.

Since 2013, the United States has been a key player behind several high-profile corruption and organized crime cases. In October 2015, Yankel Rosenthal, the nephew of wealthy business magnate and former Liberal vice president Jaime Rosenthal, was arrested by American authorities in Miami. Shortly after his arrest, the US District Court for the Southern District of New York unsealed an indictment against Yankel Rosenthal, Jaime Rosenthal, Jaime’s son Yani Rosenthal and a company laywer. The US Treasury added the Rosenthals and their businesses to the ‘Kingpins list’ (Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act) at the same time. Jaime Rosenthal, the patriarch of one of the most powerful elite families, owned Grupo Continental, a large business conglomerate with a diverse portfolio including a major bank (Banco Continental), media (Tiempo newspaper, TV channels), finance, insurance, real estate, meatpacking, cement and agro-industry. The Rosenthals, who are of Bessarabian Jewish ancestry, were also a major Liberal faction: Jaime was first vice president (1986-1989), congressman (2002-2006) and unsuccessful presidential candidate in the 2005 primaries; his son Yani Rosenthal was minister of the presidency under Mel Zelaya (2006-2007), a congressman (2010-2014) and runner-up in the 2012 Liberal primaries (with hopes for another presidential run in 2017); Yankel Rosenthal was JOH’s investment minister until June 2015. The Rosenthal family is accused of money laundering for the Cachiros drug cartel. The Cachiros (Rivera Maradiaga family), who owned one of the main cattle ranching businesses in the north, sold cattle to the Rosenthal’s meatpacking plant and opened accounts with Banco Continental. In 2006, the Rosenthal started lending money to the Rivera Maradiaga’s cattle and milk businesses – and later their African palm plantations. Banco Continental became a major investor in the Cachiros’ successful zoo and eco-park. Yankel and Yani Rosenthal have both pleaded guilty in the US, but Jaime Rosenthal remains a fugitive in Honduras despite an extradition order.

Candidates and Campaigns

There were 9 presidential candidates, three of them ‘important’.

Incumbent president Juan Orlando Hernández ran for reelection, a first in recent Honduran politics made possible by the Supreme Court’s controversial 2015 decision to allow presidential reelection. JOH was born in Gracias (Lempira) to a coffee-growing family. He attended a military academy and graduated with a bachelor’s from the Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH) and a master’s from SUNY-Albany. He is married to Ana García Carías, a direct descendant of former dictator Tiburcio Carías Andino (1933-1946).

Incumbent president Juan Orlando Hernández ran for reelection, a first in recent Honduran politics made possible by the Supreme Court’s controversial 2015 decision to allow presidential reelection. JOH was born in Gracias (Lempira) to a coffee-growing family. He attended a military academy and graduated with a bachelor’s from the Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH) and a master’s from SUNY-Albany. He is married to Ana García Carías, a direct descendant of former dictator Tiburcio Carías Andino (1933-1946).

He got his first job in politics as assistant to his brother, Marco Augusto, who was first secretary of Congress and connections to the National Party’s top echelons. JOH was elected to Congress as deputy from Lempira in 1997, and went on to serve four terms in the legislature. Rising through the ranks of the Nationalist leadership, he was leader of the Nationalist caucus (2005-2009) and later president of Congress (2010-2013). JOH became a key Nationalist power-broker, who supported Pepe Lobo’s 2005 and 2009 presidential campaigns and spearheaded the administration’s legislative agenda in Congress. Some of the laws adopted under JOH’s tenure as president of Congress were mentioned above – ‘security tax’, tax reform, ‘model cities’, military police (PMOP), first attempt at police depuration, national security and defence council, wiretap law and public-private partnerships. As president of Congress, JOH also stage-managed the controversial and almost certainly illegal ‘purge’ of four of the five members of the constitutional section of the Supreme Court in 2012. Having consolidated control of party structures and formed lucrative connections to other elite sectors, JOH manoeuvred his way to the presidential nomination in the 2012 primaries. His main rival was Tegucigalpa mayor Ricardo Álvarez. who was later brought under control as JOH’s first vice president – although JOH has still tried to screw him over, most notably by sneakily implying that he should take the blame for the IHSS scandal. JOH was elected president in 2013.

His record in government is thoroughly detailed in the previous section and hardly needs greater explanation. According to his critics, JOH is an autocrat who has concentrated most state powers – including those ostensibly held by independent institutions and control agencies – in the executive branch. As explained above, JOH has expanded the military’s power and influence, surrounding himself with powerful ‘securocrats’ of military extraction like his brother Amílcar and retired general Julían Pacheco (security minister). Like in the 1970s and 1980s, retired military personnel have also been appointed to head civilian agencies like civil aviation, ZEDEs, the housing authority, the port authority and the agricultural marketing institute. The judiciary, already weak and politicized, was further weakened and politicized by JOH. This weakened and politically favourable judiciary led to the 2015 decision declaring inapplicable the constitutional ban on reelection. The new Supreme Court elected by Congress in early 2016 (not without drama) is just as politicized (and of questionable competence) as previous courts.

JOH is well connected to the country’s elites – both traditional political elites, transnational economic elites and, to a certain degree, new illegal elites. According to InSight Crime’s report on elites and organized crime in Honduras, JOH “reportedly owns coffee farms, amongst other agricultural holdings, as well as hotels, and radio and television stations” and “has been linked to a mysterious lobbying group called Colibrí, which has reportedly engineered lucrative government contracts and kickback schemes for its members and supporters” (p. 47). Unlike his predecessor, JOH isn’t directly connected to local drug lords, although there are questions about some of his ‘securocrats’. He has also politically associated with and supported Nationalist politicians directly connected to organized crime. Hugo Ardón, who ran his 2013 campaign in western Honduras and then ran the highway authority until 2015, is the brother of Alexander Ardón, former mayor of El Paraíso (Copán), suspected of being part of the mysterious ‘AA Brothers’ drug trafficking network. As noted in the historical background section, Devis Leonel Rivera Maradiaga (Cachiros cartel) claimed in US federal court that he had bribed Tony Hernández, the president’s brother, in return for settling debts owed to a Cachiros-owned company which had done roadwork for the government. In 2016, a former national police chief who detailed how drug traffickers financed politicians, had said that Tony Hernández (“the brother of The Man”) was the National Party’s go-to man for drug money and connected to Alex Ardón’s drug trafficking network.

As achievements, JOH can claim the reduction in homicide rates, the general improvement in security (even if the means to achieve those ends are controversial) and a relatively strong economy with sounder financial indicators. For people on the right of the political spectrum, they will likely appreciate the government’s pro-business policies – although, as explained above, the façade of ‘open for business’ likely hides a system of corrupt crony capitalism beneficial to a small circle of connected elites. The United States sees in JOH a key regional ally – on drug trafficking, the ‘war on drugs’, business, trade regional political stability and balance and even on immigration. The government’s official communications presents a long list of achievements, successes, programs, international praise and ambitious future goals.

Cleared to run for an historic second consecutive term by the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision, JOH announced his reelection bid in November 2016. Supported by two Nationalist factions (Unidos and Juntos), JOH won his party’s primaries in March 2017 with 92.6% of the vote against the candidate of the Monarca faction of former president Rafael Callejas (1990-1994). Callejas was one of the petitioners in the legal challenge to the ban on reelection, and fully intended to run for president once the verdict dropped. However, Callejas, who was president of the Honduran football federation from 2011 to 2015, was extradited to the US in December 2015 facing bribery charges in the FIFA scandal. He pleaded guilty in US federal court to racketeering and corruption charges in March 2016.

JOH’s presidential campaign – in public – largely focused on continuing down the current path, ‘for more changes’. As is usual in Latin American presidential campaigns, JOH set out ambitious objectives for the next four years (pie in the sky?) like promising that, in 2022, Honduras will be admired and an example for both the region and the world. The seven pillars of his platform were vague aspirations and goals: productive innovation (i.e. attracting businesses), access to credit, Honduras as the ‘logistical centre’ of the region (see above), education (better schools! internet! bilingual system! massive bursaries!) and healthcare (universal access to healthcare and pensions), security (continuation of current policies, new prisons), economic stability (pro-business and investor confidence) and transparency.

The main opposition candidate was Salvador Nasralla, the candidate of the Opposition Alliance against the Dictatorship (Alianza de Oposición contra la Dictadura) or ‘Alianza’, an electoral coalition between former president Manuel Zelaya’s left-wing Libre party (Libertad y Refundación) and the old minor centre-left Innovation and Unity Party (Partido Innovación y Unidad, PINU). Nasralla is a former businessman, sports journalist, TV presenter and master of ceremonies who became a politician in 2013, running for president and placing a surprisingly strong fourth with 13.4%. Fitting with his past career, he has a loud, direct, exuberant and boisterous personality. His critics have described him as selfish, egocentric and narcissistic.

The main opposition candidate was Salvador Nasralla, the candidate of the Opposition Alliance against the Dictatorship (Alianza de Oposición contra la Dictadura) or ‘Alianza’, an electoral coalition between former president Manuel Zelaya’s left-wing Libre party (Libertad y Refundación) and the old minor centre-left Innovation and Unity Party (Partido Innovación y Unidad, PINU). Nasralla is a former businessman, sports journalist, TV presenter and master of ceremonies who became a politician in 2013, running for president and placing a surprisingly strong fourth with 13.4%. Fitting with his past career, he has a loud, direct, exuberant and boisterous personality. His critics have described him as selfish, egocentric and narcissistic.

15 years older than JOH, Nasralla was born in Tegucigalpa to Lebanese parents (although his mother was born in Chile). He began working dabbling in radio journalism as a teenager. Between 1970 and 1976, he studied industrial civil engineering at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile – a period overlapping with the 1973 Chilean coup and the first years of Pinochet’s regime. Thanks to his friendship with the dictator’s son, Marco Antonio Pinochet, he scored an interview with Augusto Pinochet some years later in 1984 on the occasion of the Viña del Mar festival. In a recent interview with the Chilean newspaper La Tercera, Nasralla said that he does not admire Pinochet but that he saw how Chile went from an impoverished country with queues for everything to a ‘Latin American power’ because of Pinochet and the Chicago Boys’ economic policies.

Back in Honduras, Nasralla was general manager of Pepsi-Cola Honduras for six years and an engineering and administration professor at UNAH for eight years, before quitting the university complaining about the low academic level of the students. Nasralla became famous as a sports commentator on TV in the 1980s, serving as press officer for the national football team during the 1982 FIFA World Cup. He was disliked by radio commentators and became know for heated arguments with referees, managers, owners, colleagues and even politicians (and fanatic commentating). In 1990, he started hosting a very popular game show program. Throughout his TV career, Nasralla also hosted various special events or programs, from the Viña del Mar festival in Chile to beauty pageants like Miss Honduras.

Nasralla was a bachelor until very recently, which fed rumours that he was gay. Nasralla rejected such rumours by assuring everyone that he is a macho and that many women can vouch for his sexuality. In a very creepy and disturbing 2016 interview, he said that he has had sex with ‘more than 700 women’, that he has never used viagra and that every woman who has had sex with him was satisfied (he also gives his ‘tactics’ to ‘conquer women’). Nasralla claimed that his busy life always prevented him from getting into serious relationships with women. In March 2016, he married former Miss Honduras 2015 Iroshka Elvir, who is 38 years younger than Nasralla (he is 64, she is 26). There are many pictures of their honeymoon on Google Images, and they are rather creepy. Their first child was born a few weeks after the election. In an interview which caused a bit of a stir in Israel, Iroshka Elvir said that Adolf Hitler was a great leader and that her personal political icons included John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Eva Perón, Margaret Thatcher and Angela Merkel. She later apologized for her ‘misquoted’ Hitler comment; according to The Times of Israel, in her apology she “attached a photo where she is portrayed holding an Israeli flag and closed the message with ‘Shalom’.” Iroshka Elvir was a PINU congressional candidate in Francisco Morazán department (Tegucigalpa).

With his fame as one of the country’s most famous TV personalities and his loud, direct and flamboyant personality (am I the only one seeing the parallels with Donald Trump?), Nasralla created his own political party – the Anti-Corruption Party (PAC) – and ran for president in 2013. As his party’s name suggests, Nasralla’s campaign focused on corruption – consisting mostly of endless rants against corrupt politicians, mostly targeting the National Party. Nasralla placed fourth with 13.43%, doing particularly well in San Pedro Sula (Cortés department). However, confident that he would win in a landslide, Nasralla refused to admit defeat and still claims that he is certain that he won the election and that over 636,000 votes were stolen from him.

In a rather absurd chain of events, Nasralla lost control of his own party (the PAC) earlier this year to rebellious factions led by PAC deputy Marlene Alvarenga. In April 2017, Nasralla’s faction organized internal elections (with a single candidate) which were not recognized by the TSE for violating electoral law. In May 2017, the rival Alvarenga-led factions of the PAC organized their own internal elections, which were recognized by the TSE and therefore left Nasralla’s party in the hands of dissidents. In parallel to that, however, Nasralla was proclaimed as the opposition alliance’s presidential candidate – an alliance formed by former president Manuel ‘Mel’ Zelaya’s left-wing Libre party, the old minor centre-left PINU and some minor dissident groups from both the Liberal and National parties. In 2013, Mel Zelaya’s wife, Xiomara Castro, placed second behind JOH (she too claims she won) with 28.9% and Libre became the main opposition party with 37 seats – an historic showing which broke the old duopoly. Given the Supreme Court’s decision on reelection, Manuel Zelaya also became eligible to run for president in 2017, and he publicly considered it before ruling it out – because he now opposes reelection (which the alliance says is illegal) and, officially, ‘sacrificing personal interests for national interests’.

Nasralla and his followers (6 congressmen) was ‘welcomed’ by the PINU after losing control of the PAC. Many of Nasralla’s allies – including his wife, Iroshka Elvir – appeared on PINU’s congressional lists (Libre and PINU ran separately in congressional and municipal elections). Mel Zelaya was the ‘coordinator’ of the Alliance. Nasralla’s three running mates were Xiomara Castro (Zelaya’s wife and Libre candidate in 2013), PINU leader Guillermo Valle (whose sister, Beatriz Valle, ambassador to Canada under Mel Zelaya, is a Libre congresswoman) and Belinda Martínez (Libre). The anti-Zelaya newspaper El Heraldo argued that Salvador Nasralla was ‘absorbed’ by Libre’s ideology, policy and leadership. Nasralla’s opponents (and the right, in Honduras and abroad) painted him as a ‘pawn’ of Mel Zelaya and Libre. Nasralla rejected claims that he was a left-winger, declaring himself to be a centrist.

Nasralla’s campaign focused primarily on attacking JOH and the Nationalists (mostly for being corrupt and authoritarian), in his trademark melodramatic and hyperbolic rhetorical style. Nasralla and the opposition alliance’s platform, however, did show the strong influence of Libre and Mel Zelaya’s ‘left-wing’ views – not only in the actual policy proposals, but also the language, replete with references to the 2009 coup. Structured around 14 axes, the first of which was the ‘refoundation’ of the country and fighting corruption – proposing a plebiscite to decide on the ‘mechanism’ to write a new constitution (very similar to Mel Zelaya’s cuarta urna in 2009) and asking the UN to create a Guatemalan-like international commission against impunity and corruption (‘CICIH’, a local equivalent of Guatemala’s CICIG). Mel Zelaya said that, if the opposition won, there would be a constituent assembly (which the hostile press quickly tied to Nicolás Maduro’s constituent assembly in Venezuela). He also said that Nasralla’s presidency would be a ‘transition government’, never bothering to explain what was meant by that. Given the recent antecedents of constituent processes in Honduras (and Maduro’s constituent assembly), this idea was particularly controversial and seized upon by the Nationalists to attack Nasralla as a ‘puppet’ of Mel Zelaya (and raise the ‘leftist threat’).

The Alliance proposed a rather left-wing ‘alternative economic model’ – eradicating poverty, reverting privatizations, regulation of tax exemptions for corporations, progressive taxation, reducing consumption taxes, auditing the public debt, reviewing commercial treaties, promoting different types of property (mixed, private, shared etc.), provision of liquidity through the public bank to reduce interest rates and finance employment-generating activities and provision of credit and technical assistance to ‘productive sectors’. Nasralla also promised to repeal ‘harmful’ economic laws like the ZEDEs, Coalianza and a ‘fiscal responsibility law’ (limiting deficits). The platform further promised an ambitious laundry list of infrastructure projects, all while striking a very ‘green’/environmentalist tone on environmental issues (green economy, fourth generation rights, revision of 300+ mining concessions). The Alliance’s platform also promised universal public education, guaranteed universal access to healthcare, a public healthcare system and social housing (500,000 new houses in 4 years).

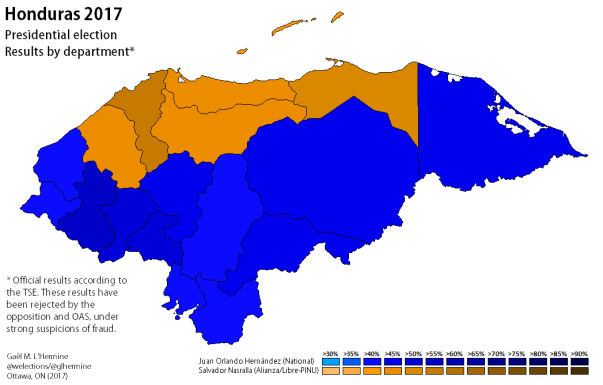

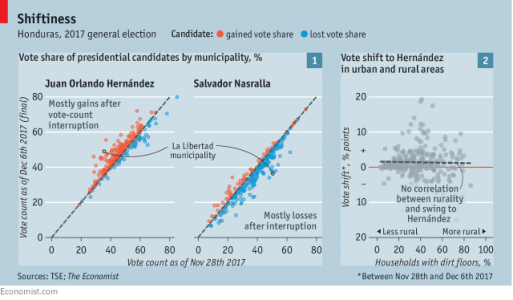

On security matters, Nasralla attacked JOH’s ‘militarization of society’ and claimed that violence is increasing considerably despite Nationalist denials. He said that he would continue with extraditions, but limit the armed forces to their constitutional role with the national police in charge of public security. The platform detailed a security strategy built around ‘prevention, dissuasion and control’. Some were worried by Nasralla’s announcement that he would review police depuration and the cases of police officials removed by the depuration commission, claiming that they were removed without due process and some may have been removed for investigation political corruption or criminal ties.