Category Archives: Switzerland

Swiss Referendums 2014

Referendums on three matters were held in Switzerland on February 9, 2014. One issue was a mandatory referendum, because it modified the Swiss Constitution and the other two were popular initiatives which were placed on the ballot after they gathered 100,000 signatures from voters.

Turnout on the three votes ranged from 55% to 55.8%, a rather high level in a country where turnout in both elections and referendums is usually below 50% (or barely above).

Popular initiative “against mass immigration”

The popular initiative “against mass immigration” was presented by the right-populist Swiss People’s Party (SVP), the largest party in the Swiss Parliament which is well known for its nationalist and anti-immigration positions.

Contrary to popular perceptions, Switzerland isn’t quite an exclusive cocoon made up of Swiss citizens. In 2012, foreigners made up 23.3% of the Swiss population (about 1.87 million people), the highest number and percentage in the country’s recent history. About 64% of foreigners are EU and EFTA citizens (especially from neighboring Germany, Italy and France or countries such as Portugal); there are significant Serbian (6% of all foreigners), African (4.1%) and Turkish (3.9%) communities in Switzerland. Overall, 85% of foreign residents are European. Additionally, 34.7% of Swiss residents have ‘immigration background’ – including naturalized Swiss citizens and first/second generation foreigners.

Switzerland signed an Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons with the EU (which also applies to EFTA member-states) in 1999, allowing for the free movement and employment of EU and EFTA citizens in the country. Immigration of non-EU/EFTA citizens is strictly limited, with the country largely admitting only qualified professionals and other skilled workers. Swiss companies must prove that they failed to find adequate Swiss or European workforce when employing non-EU/EFTA foreigners. Asylum seekers and refugees are not covered by these regulations.

Immigration has increased significantly since 2008, with the economic crisis. Since 2007, immigration has increased by about 80,000 per year. In 2002, when the agreements on freedom of movement came into force, the Federal Council estimated that there would be about 8,000 immigrants per year – the reality has been 10 times higher. The large number of new immigrants in Switzerland created real problems in terms of housing shortages, overstretched transportation infrastructure creating traffic jams or overcrowded trains and major pressure on jobs, wages and rents.

The situation is made even more problematic by Switzerland’s longstanding tradition of relative isolationism. On the right, there has been a significant emphasis on the protection of ‘Swiss identity’ or ‘Swiss jobs’. This isn’t the first popular initiative dealing with the issue of immigration or the feeling of ‘too many immigrants’. In 1970, an initiative by the far-right National Action which wanted to limit the foreign population to 10% by canton (25% in Geneva) was narrowly rejected, with 54% against. In 1974, a very similar text pushed by the same group, which proposed to limit the country’s foreign population at 500,000, was rejected by a wide margin (65.8% no). Two similar initiatives were rejected by huge majorities in 1977. These first anti-immigration initiatives took place following the first significant surge in the foreign population (in the 1960s and early 1970s). While unsuccessful, the environment created by these initiatives pushed the Federal Council to pass stricter immigration laws which led to a sharp dip in the foreign population after 1975 and until 1990.

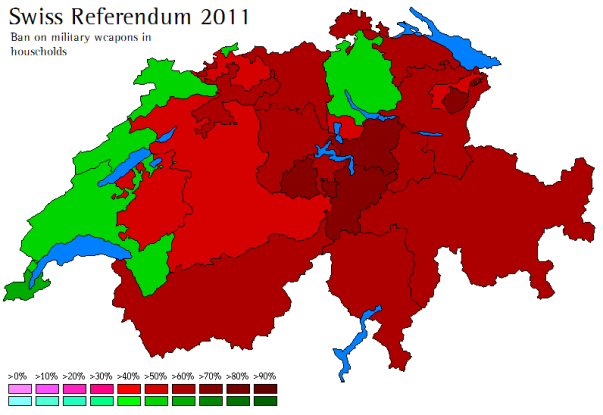

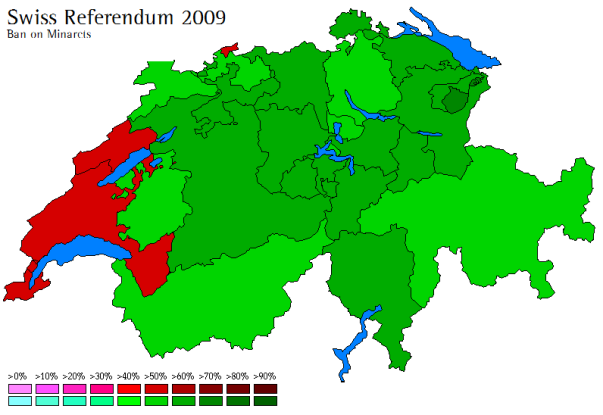

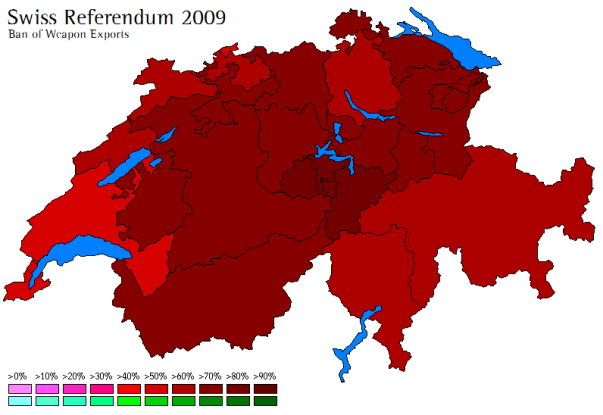

Beginning with another National Action proposal in 1988, the 1990s and 2000s saw another wave of anti-immigration initiatives – mostly proposed by the SVP, which at the same time saw its popular support expand significantly, becoming the single largest party in 2003. In 1996, a popular initiative “against illegal immigration” proposed by the SVP was rejected with 53.7% against. In 2000, a popular initiative proposing to limit the foreign population at 18% of the country’s population was rejected with 63.8%. In 2002, a SVP initiative seeking to strictly limit the conditions for the admission of asylum seekers was rejected by a very narrow margin – with 50.1% against. In 2009, a controversial initiative banning the construction of minarets was approved with 57.5% of the vote. In 2010, a SVP popular initiative “for the expulsion of foreign criminals”, which allows for the expulsion of foreigners convicted of serious crimes or having illegally received welfare benefits. The SVP’s initiative was approved by 52.9% of voters. The SVP unsuccessfully opposed the approval of Swiss membership in the Schengen Area (in 2005) and the extension of the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons to the new EU member states in 2005 and to Romania and Bulgaria in 2009.

This popular initiative “against mass immigration” asked that Switzerland manages autonomously immigration through annual quotas and ceilings (without specifying what the levels would be). This would apply to all categories of foreigners including foreign workers and their families, asylum seekers, refugees and trans-border workers. Employers would need to give preference to Swiss nationals, and the initiative bans the ratification of international treaties contravening these regulations. This would imply the renegotiation or even full denunciation of the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons with the EU; the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons is one of Switzerland’s Bilateral Agreements I with the EU and the termination of one of these agreements leads to the automatic cancellation within six months of the other agreements.

The initiative committee blamed the massive increase in immigration for higher unemployment (8% with foreigners), overcrowded trains, traffic jams, rent increases, the loss of arable land, pressure on salaries, ‘foreign criminality’, asylum abuse and a large number of foreigners on welfare. ‘Uncontrolled immigration’, according to the initiative’s backers, threatens Swiss freedom, security, full employment, natural beauty and Swiss prosperity. In presenting the initiative, they stressed that it did not want to ‘freeze’ immigration or terminate bilateral agreements with the EU.

The Federal Council and Parliament recommended the rejection of the initiative. In its official recommendation, the Federal Council argued that Switzerland is dependent on foreign labour and that immigrants contribute to the Swiss economy. Above all, however, they sought to point out that the approval of the initiative would necessarily mean a renegotiation of the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons (which, according to the government, the EU is unwilling to undertake). A failure to renegotiate the agreement would, as aforementioned, automatically terminate all parts of the Bilateral Agreements I. Given Switzerland’s close economic and trade ties with the EU, termination of the Bilateral Agreements I would have, according to the Federal Council, serious consequences on the economy. The government recognizes immigration’s impact on housing and infrastructure, but argue that they would exist even without immigration and therefore require internal policy reforms rather than ‘administrative obstacles’ and ‘unnecessary annoyances’ entailed by the initiative.

Every major party except the SVP recommended the rejection of the initiative. However, while the Swiss Green Party at the federal level recommended a no vote, the Ticino section of the Green Party supported the yes. The SVP, as in the past, played a lot on sensationalist (but misleading) statistics – for example, a newspaper ad claiming that by 2060, there would be more foreigners than Swiss citizens – based on an exponential growth in the foreign population and a slow growth in the Swiss population. But with the same ‘projections’ playing on stats, we can also ‘project’ that the SVP will be winning 69% in 2060! The SVP also knew how to frame its argument: in a fairly moderate way, claiming that Switzerland could reject mass immigration without endangering bilateral agreements with the EU; and by playing on simple bread-and-butter issues – the nefarious effect of immigration on housing, wages, infrastructure, ‘freedom’ and unemployment (although some studies show that immigration hasn’t had a negative effect on the job market). It also played on deep-seated Eurosceptic sentiments, by using the Federal Council’s arguments on EU reprisals to appeal to opposition to ‘EU diktats’, the ‘European elites’ and a desire to ‘stand up’ to ‘EU scaremongering’ and defending Swiss sovereignty.

Do you accept the popular initiative “against mass immigration”?

Yes 50.3%

No 49.7%

Early polling had the anti-immigration initiative going down to defeat, but the gap narrowed significantly in the yes’ favour in the final days. The initiative was narrowly approved with a 19,526 vote majority (0.6%). The initiative’s implications are interesting and significant. Like the minaret initiative, the Swiss vote hit a nerve in the EU and has placed the contentious issue of immigration (and limits on immigration) at the top of media attention and public opinion interest in many EU countries dealing with the same issue – France, Austria, Italy or the UK, for example. It has sparked widespread condemnation in the foreign media and many political leaders, with – in my mind – appropriate comments on xenophobic sentiments and the rise of anti-immigration opinion in Switzerland. Regardless of one’s opinion and appreciation on the Swiss vote, it would be best not to give lessons of morality. For example, I have little doubt that France could potentially approve a very similar initiative if such an issue came up in a referendum (a 2013 poll showed that about 70% of French voters felt that there were too many immigrants in France).

The initial official reaction by the EU has been negative: in a brief statement on February 9, the European Commission said that the initiative “goes against the principle of free movement of persons between the EU and Switzerland” and that it would “examine the implications of this initiative on EU-Swiss relations as a whole.” The French foreign minister and German finance minister both expressed concern; the issue is particularly important for France, Germany and Italy who have a large number of trans-border workers (frontaliers): citizens of those countries who either live and work in Switzerland or commute to work in Switzerland.

At the same time, the European far-right as a whole is rather giddy about the issue: Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders, Heinz-Christian Strache, Matteo Salvini but also Nigel Farage, the German AfD and Norway’s FrP all welcomed the result and would like similar votes in their own countries.

The Swiss Federal Council will respect the result and present legislation to implement the initiative by the end of the year, and immediately begin negotiations with the EU – the initiative gives them a three year period to renegotiate existing agreements with the EU. Many Swiss politicians and their constituents are confident that the EU will not choose confrontation and that some kind of agreement will be found between the two countries. Some feel that, in the long run, the initiative won’t change much: the cantons may gain considerable leeway in setting quotas, allowing diverse and immigrant-heavy cantons (Basel, Geneva, Zurich etc) to set large quotas; the implementing legislation may be challenged in a referendum; international law will still apply and Switzerland will need to abide by it (although the SVP fancies an initiative to make Swiss law supersede international law) and the very drawn out process for renegotiation will allow for adaptation or compromise. If the negotiations were to collapse, however, it would have major economic consequences for Switzerland and the EU: some sectors of the Swiss economy are compelled to turn to foreign labour for lack of domestic labour, many Swiss take advantage of bilateral programs with the EU (Erasmus, for example), Switzerland is closely connected to the EU economy and Swiss participation in EU projects may be jeopardized. Swiss businesses are worried, fearing an overload of administrative annoyances and starting in a disadvantageous position in EU negotiations (the EU will likely demand concessions from Switzerland in case of a compromise).

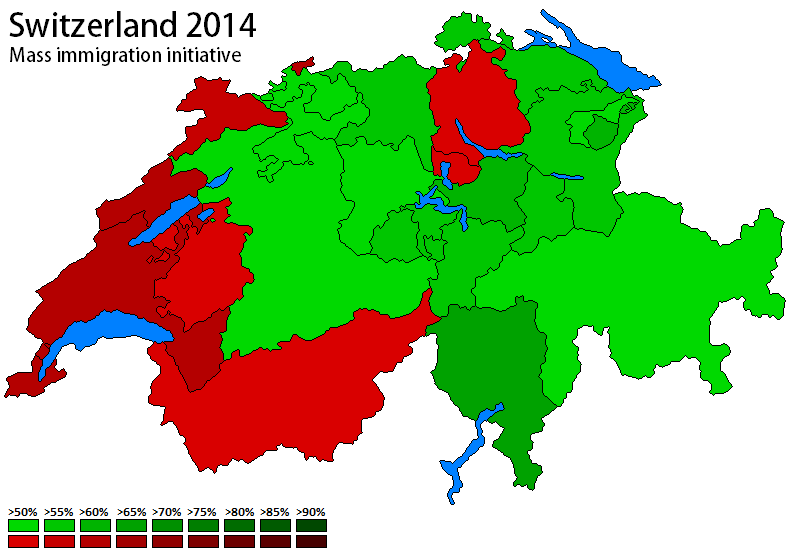

There has been significant attention paid to the geography of the vote, even in the foreign press which usually ignores electoral geography. The overall geography was not very different from past votes on foreigners/immigration-related votes in Switzerland: anti-immigration votes tended to come from German but also Italian Switzerland – and rural areas – while support for the pro-immigration position came from French Switzerland and urban areas in general. Once again, French Switzerland only gave 41.5% support to the initiative, compared with 52% in German Switzerland and 68% in Italian Switzerland. The strongest support for the initiative came from the Italian canton of Ticino, which voted yes with no less than 68.2%. Ticino, like Geneva (which voted no, with 61%), has the highest unemployment in the country (around 7%, in a country where unemployment is only 2-3%); but the main reason for the canton’s strong support for the initiative is because it has been impacted by significant labour immigration from neighboring Italy. Well-educated but unemployed Italians are willing to cross the border to accept jobs in Ticino – at higher salaries than in Italy, but at significantly lower salaries than Swiss workers. The canton of Ticino has voted against ‘free movement’ issues in the past: in 2009, 66% voted against the extension of freedom of movement to Romania and Bulgaria (38% in Switzerland as a whole); in 2005, 64% voted against the extension of freedom of movement to the 2004 EU entrants (40.6% in the country); in 2004, 62% voted against Schengen (45% in the country); and in 2000, 57% voted against the sectoral agreements with the EU which were approved by 67% of voters. This year, there was little rural-urban divide in Italian Switzerland: 66% approval in urban areas, 69.6% approval in rural towns.

Support for the initiative was also strong in German-speaking rural areas: in the rural communities, 60.7% voted in favour. The very conservative Catholic canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden approved the issue with 63.5%, the predominantly rural (and also Catholic) canton of Schwyz – which often records strong support for anti-immigration votes (it too voted against the Romania/Bulgaria extension, and was the only one to back a 2008 SVP initiative which would have subjected naturalization applications to popular votes in each town) – voted yes with 63.1%. The next highest results in support of the initiative were recorded in Glarus (59.4%), Obwalden (59.1%), Nidwalden (58.8%) and Uri (58.2%). With the exception of Glarus, which has been industrialized over 100 years ago, all the other cantons are peripheral, historically rural and and traditionally poor German Catholic cantons. The cantons of Schwyz, Uri and the half-cantons of the Unterwalden formed the original four cantons of the Swiss Confederation in 1291, were the central part of the anti-centralist and conservative Sonderbund in 1847 and have long been peripheral, isolated, patriarchal and strongly traditionalist/conservative. Glarus, which was historically Protestant and industrialized, proved more open to external influences but it has become conservative in the post-war era. These cantons have often recorded the strongest opposition on votes concerning European integration (EEC membership in 1992), UN membership (2002), immigration but also other issues (abortion, gun control).

The initiative also received strong support in rural and small town conservative areas throughout German areas, for example in the cantons of Aargau (55.2%), Thurgau (57.8%), Schaffhausen (58.1%) and Saint Gallen (55.9%). Far less rural and traditionalist than the original four cantons, these German cantons have nonetheless become – outside of their main urban centres – quite conservative. It passed by a narrow majority in Lucerne (53.3%), Solothurn (54.6%), Bern (51.1%), Grisons (50.6%) and Basel-Landschaft (50.6%). In the cantons of Bern and Lucerne, the initiative was carried exclusively by strong support in rural conservative areas: it received only 39.7% support in Lucerne and 27.7% in Bern. However, for example, in the rural districts of Entlebuch (LU) and Obersimmental-Saanen (BE), the yes won 67.4% and 66.7% respectively. The initiative was also defeated in the cities of Aarau, Baden, Winterthur and Saint Gallen.

In the canton of Grisons, a mountainous and fairly conservative canton, the rather high level of opposition to the initiative might have something to do with the importance of tourism in the canton, which is home to internationally famous high-end ski resorts and has created a fairly high demand for foreign labour (the foreign population reaches 30.6% in the Maloja district, which includes Saint-Moritz). In the Italian-speaking district of Moesa in Grisons, the yes won 71% of the vote – it also won 58% in the district of Bernina, an Italian-speaking valley. It failed in the canton’s main city (Chur) and most major resort towns, including Davos and Saint-Moritz.

The cantons of Basel-Stadt (39% yes), Zurich (47.3% yes) and Zug (49.9% yes) voted against. The first two cantons are anchored by large urban areas, which voted heavily against – in the city of Zurich itself, the yes won only 33.4%. In German Switzerland, there was a very strong rural-urban divide. In German urban areas, the yes vote received only 41% (keeping in mind that, in contrast, it took 61% in the most rural German communities); the yes vote was successful in medium-sized towns (52.9%) and isolated towns (53.9%). The cities, as in every other country, concentrate multicultural communities with more leftist views on issues such as immigration and highly-educated professionals – either wealthier suburbanites (District 7/8 in Zurich) or ‘new middle-classes’ in gentrified downtowns (Districts 4/5 in Zurich) with similar socially liberal views. In Zurich, the initiative was defeated by huge margins both in the very wealthy suburban districts (7+8, 27.7% yes) and the central gentrified areas (Districts 4/5, 21.1% yes); it carried only District 12, a lower-income/blue-collar peripheral district (52% yes). The initiative also lost by significant margins in Zurich’s very wealthy lakeside suburbs (43.9% yes in Meilen district, 46.6% in Horgen district). In Basel, a major economic centre closely connected to neighboring Germany and France (many German and French nationals commute cross-border), the initiative won only 38.7%; it was also defeated in its affluent, well-educated suburbs. The canton of Zug is the country’s wealthiest canton; as a low-tax zone, the city of Zug has become home to the headquarters of many multinational corporations. In the city of Zug itself, the initiative won 43.1% support.

French Switzerland (Suisse romande) was the only region to reject the initiative, with only 41.5% support. It won about 39% support in the cantons of Geneva, Vaud and Neuchâtel; it did slightly better in the Jura (44%) and failed only narrowly in the cantons of Fribourg (48.5%) and Valais (48.3%). In the case of the latter canton, there was a clear linguistic divide: the German-speaking eastern half of the Valais (Oberwallis) voted in favour, while all but one district in the French-speaking western half (Bas-Valais) voted against. In the canton of Fribourg, which has a substantial German minority, the German-majority district of Sense was more heavily in favour (56.7%) than French-speaking rural district, but in that canton the divide was more urban-rural: the initiative failed by a landslide in the city of Fribourg (34.3%) and its suburbs but was successful in rural areas. On the whole, French-speaking Switzerland has been the country’s most liberal region; voting in favour of European integration and choosing the more liberal option on matters such as immigration, identity, abortion or women’s rights.

It is worth noting, however, that there is a strong rural-urban divide in French Switzerland as well. In urban centres, the initiative received only 37.7% support. It won 40.6% in me

dium-sized towns, 42.2% in isolated towns and 47% in rural areas. The cities of Geneva (37.9% yes), Lausanne (32.5% yes), Neuchâtel (31.2% yes), La-Chaux-de-Fonds (39.8% yes), Delémont (32.3% yes), Porrentruy (38.7% yes), Nyon (36.2% yes), Montreux (40.7% yes) and Sion (40.4% yes) all voted heavily against. Opposition was very strong in the arc lémanique, a very affluent urban/suburban area around the Lac Léman from Geneva to Lausanne. The Geneva-Léman region is home to a large number of international organizations and attract a large number of cross-border workers from France; foreigners constitute about 40% of the population in the canton of Geneva and in Lausanne, and 34% in the district of Nyon (VD). In the affluent Geneva lakeside suburb of Collonge-Bellerive, the initiative won only 35%; support was below 40% in most affluent towns in the arc lémanique. On the other hand, support was higher in less affluent areas in the Ouest lausannois and in Geneva’s suburbs; 42.6% in the Ouest lausannois district and 49.1% in the town of Vernier, a poorer suburb outside of Geneva. That being said, plenty of historically working-class and poorer cities in French Switzerland voted heavily against: the industrial cities of La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Delémont and Le Locle all voted against by substantial margins; the French-speaking valleys of the Bas-Valais are no more or less affluent than the German-speaking Oberwallis yet the former voted against while the latter voted in favour by large margins. In French Switzerland, the initiative was only successful in rural areas: the eastern ends of the canton of Vaud, the Jura bernois (in the canton of Bern) and much of the canton of Fribourg outside urban areas.

While the initiative’s victory is a major political success for the SVP, it would not have been successful without the support of voters outside of the SVP’s traditional electoral base. The SVP’s electoral base is, at most, no more than 30%; the core hardline anti-European and anti-immigration electorate in referendums is often 30-35% as well. Like the minaret or ‘foreign criminals’ referendums, this result shows that the SVP’s rhetoric against immigration appeals to a much wider crowd than that which usually votes for the SVP in federal elections. In this referendum, success would not have been possible without significant cross-over support from other parties and independents – including left-wingers. The left-wing argument in favour of this initiative is that the current levels of population growth, in good part due to foreign immigration, are unsustainable in the long-term for economic, social and environmental reasons.

There have been a lot of comments in the media that the regions which voted in favour are those with a low percentage of foreigners while those which voted against are those with a higher percentage of immigrants. This is not entirely the case. This graph (by district) comparing the % of foreigners to % yes for the initiative does show some kind of correlation between a low number of foreigners and stronger support for the initiative – only two districts with a number of foreigners above the Swiss average voted in favour; at the same time, however, many districts with a fairly large percentage of foreigners voted in favour. Based on the data in that chart, I calculated a correlation coefficient of -0.34 (negative correlation between support for the initiative and high percentage of foreigners), but the R² value is only 0.11, so it’s a very weak correlation.

Popular initiative “Funding of abortion is a private matter ˗ relieving the burden on health insurance by removing the costs of termination of pregnancy from basic health insurance”

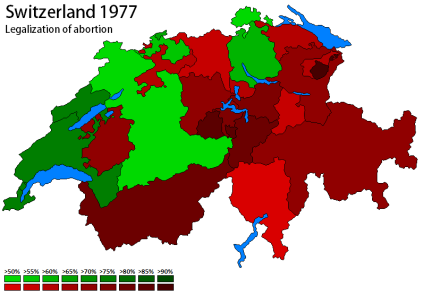

Abortion rights in Switzerland have evolved gradually. From 1942 to 2002, abortion was only permitted in the first twelve weeks of pregnancy in cases of maternal life and the mother’s health; the understanding of the term ‘health’ evolved from only physical health to cover mental health. In 1977, an initiative to legalize abortion on demand in the first twelve weeks was narrowly rejected by the electorate, with 51.7% against. In 1978, a federal law which continued to classify abortion as an offense but expanding exceptions allowing for abortions (medical and social reasons, rape, fetal defects) was struck down by a wide majority (by the looks of the vote, it displeased both the pro-life and pro-choice camps). Afterwards, the practice of abortion, albeit still legally an offense and strictly curtailed by legislation, was liberalized and the practice was only rarely prosecuted. In 2002, an amendment to the Swiss penal code legalized abortion on demand in the first twelve weeks. In a June 2002 referendum, 72% of voters approved the new law and simultaneously rejected a counter-initiative, which sought to re-criminalize abortion (81.8% against). The costs of abortions are covered, since 2002, by public health insurance.

This popular initiative proposed that abortions be no longer covered by health insurance, on the grounds of lessening the financial burden on health insurance. The text allowed for exceptions, but did not define them. The initiative was supported officially by the Evangelical People’s Party (EVP) and the SVP, although two SVP cantonal sections (Jura and Vaud) called to vote against and some other SVP sections gave no voting recommendations. Certain members of the Christian Democratic People’s Party (CVP) and the FDP.The Liberals backed the initiative. Besides lessening the financial burden on health insurance, the supporters of the text argued that, as a matter of conscience, nobody should be forced to finance abortions against their ethical and moral convictions. Other supporters argued that if abortions were to be self-financed or privately covered, there would be less abortions.

The Federal Council and Parliament recommended the rejection of the initiative. It argued in favour of the existing system, which it says has proved its worth: the number of abortions in Switzerland are low by international standards and have remained stable since 2002 (and decreased with young women under 20); strong support and counseling for women; strict guidelines to ensure quality and safety and the costs of abortions have decreased significantly (it says between 600 and 1000 CHF). The savings which would be incurred by not covering abortions would be minimal: 8 billion CHF in a system worth 26 billion CHF, so only about 0.03% of the total costs of health insurance. The Federal Council also raised concerns about the undefined ‘exceptions’ in the text of the initiative, which, they argued, would lead to patchy case-by-case financing of certain abortions.

Do you accept the popular initiative “Funding of abortion is a private matter ˗ relieving the burden on health insurance by removing the costs of termination of pregnancy from basic health insurance”

No 69.8%

Yes 30.2%

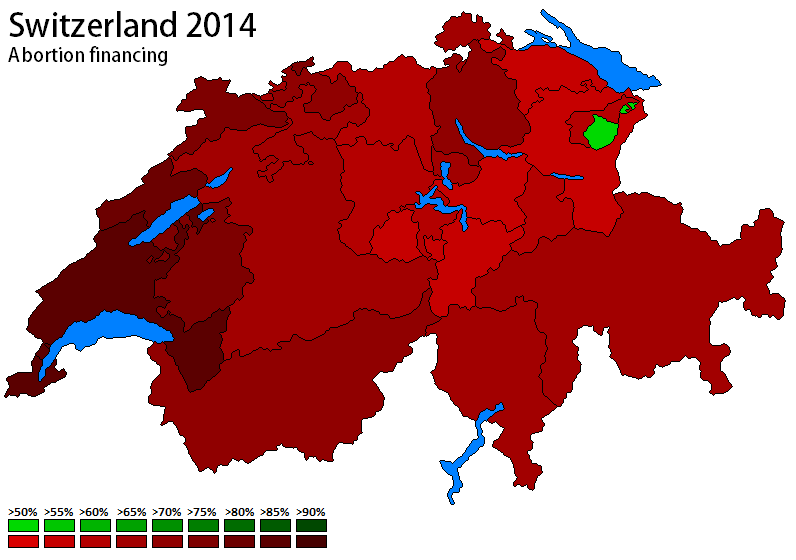

Unsurprisingly, the initiative was rejected by a very wide margin. Only a socially conservative base strongly opposed to abortion voted in favour. Outside of a socially conservative minority, abortion in Switzerland – like in many/most other Western European countries – is well accepted by the population and there is little interest in changing a system which is perceived as working well, as the Federal Council argued.

The geography of the vote was both unsurprising and surprising. Unsurprising because the very few outposts of support for the measure – only two districts and one half canton voted in favour – were rather predictable. The half-canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden, a very conservative, traditionalist and rural German Catholic region, voted in favour – with 50.9%. The district of Entlebuch, an isolated rural valley in the Catholic canton of Lucern, was the only other district to vote in favour, with 50.3%. Although it failed in every other districts, there was substantial support in some more rural districts of the cantons of Schwyz (44.3% overall), Uri (45.3%), Saint-Gallen (42.4%), Obwald (41.6%) and Thurgovia (40.9%). It was in German Switzerland where the measure found the most support, 34.5% overall, especially in German rural areas (41.2%). Swiss German cities were strongly opposed, with only 27.7% support. In the city of Zurich, the yes won 21.1% and in Basel-Stadt it got 24.6%.

In contrast, there was only negligible support in French Switzerland; where only 15.7% voted in favour, with support for the text as low as 10.9% in Vaud and 13.8% in Geneva. Over 90% of voters rejected the initiative in the city of Lausanne and the neighboring (affluent) districts of Morges and Gros-de-Vaud. Even in the French Catholic canton of Jura, the yes won barely 20.3%. Italian Catholics were slightly more supportive, with support for the text standing at 32.7% in all Italian-speaking regions.

On the other hand, the geography was more surprising because it followed the usual rural-urban and linguistic divides more than the confessional divide, unlike in the past. In 1977, when the initiative which would have legalized abortion failed, opposition was larger overall in German cantons than French cantons (regardless of religion) but the main cleavage was religion: Catholic cantons being very strongly opposed, with Protestant cantons either more narrowly against or in favour if they were urban or French. For example: the linguistically divided but religiously homogeneous Catholic canton of Valais voted no to the 1977 initiative with 82%; opposition was over 90% in Appenzell Innerrhoden, over 75% in Uri, the Unterwalden cantons and Schwyz and over 70% in Lucerne and Fribourg. In 2002, the issue was obviously far less divisive, but it still got significant opposition in the original four cantons, Valais (46% for the yes), Appenzell Innerrhoden (less than 40% for the yes), the rural districts of Lucerne and some Catholic districts in Saint-Gallen and the Grisons. Granted, a linguistic element was at work in 2002, because the Catholic cantons of Jura and Ticino voted in favour with far higher majorities for the yes than German Catholic cantons. But in this referendum, religious differences are harder to catch: on the whole, German Catholic areas were more favourable than German Protestant areas, and it can be seen in the fairly low levels of support for the measure in the Protestant cantons of Glarus (35.8% yes) and Appenzell Ausserrhoden (39.8% yes). But German Protestant rural areas still showed above-average support. The Catholic canton of the Valais had a linguistic element at work in 2002 (German districts were very strongly opposed, French districts either marginally in favour or marginally opposed), but in 2014, it appears as if the only divide in the canton (which rejected the measure with 29% – below average (!) support) was linguistic, with 20-26% support in the Bas-Valais and 43-48% support in the German Oberwallis. In the canton of Grisons, little difference is perceptible between Catholic and Protestant districts (unlike in 2002).

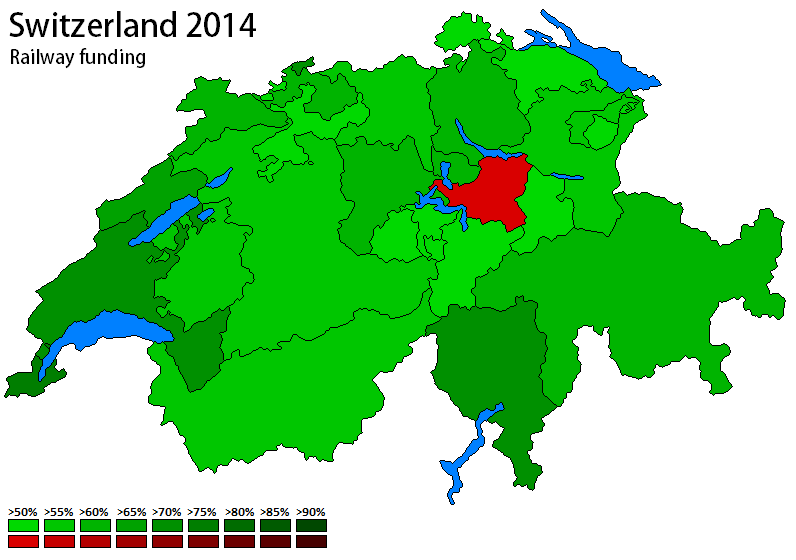

Federal decree on railway financing and development

Switzerland has a large, well developed and heavily used railway system operated by private companies and a state-owned company (the Swiss Federal Railways, SBB-CFF-FFS) which operates the huge majority of lines. However, on many lines, trains are crowded and companies are unable to offer additional trains at rush hours. The Federal Council and Parliament decided to invest in railway infrastructure by combining several federal and cantonal funds into a single permanent infrastructure fund; priority shall be given to investments in maintaining and upgrading existing infrastructure where the demands are most pressing. 80% of the funds in the new fund will come from the existing federal spending for railway infrastructure; about 1 million CHF per year will come from new sources (cantonal funds, VAT, limiting federal tax deductions for commuting). The new law also plans for the long-term development of railway infrastructure, with infrastructure upgrades on major lines and plans to allow for more trains and more space on trains. Because the federal decree modifies the Constitution, it must be ratified by the people and cantons.

The Federal Council, both houses of Parliament and all major parties except the SVP recommended the approval of the measure.

Do you accept the federal decree?

Yes 60.2%

No 39.8%

The federal decree was approved by a wide majority. Only the conservative canton of Schwyz, which has long been hostile to government intervention in the economy or a strong central/federal government, rejected the measure, by a tiny margin (49.5% yes). Opposition was fairly significant in the other original cantons of 1291 and Glarus, where the measure won less than 55% support. Overall, German Switzerland was more opposed than French or Italian Switzerland, with 59% support against 69% in French Switzerland and 71% in Italian Switzerland. There was the usual urban-rural divide in all three linguistic regions: German cities voted in favour with 69% on average but rural communities in German Switzerland only barely voted in favour on the whole (51% yes); similarly, in French Switzerland, support increased linearly with the size of the town, from 61% in rural areas to 74% in urban areas. While the main reason for opposition might likely be conservatism, it is worth pointing out that the cantons which were more strongly opposed are those which will not benefit much from the new measures by 2025 (according to a map published in the Federal Council’s document on the measure); the lines which will be improved are those linking major urban areas.

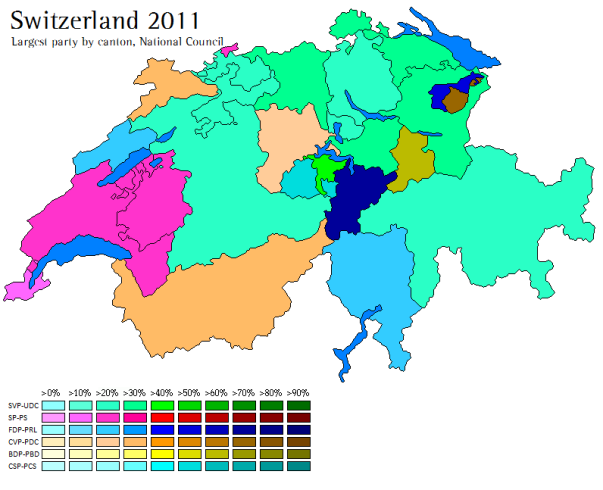

Switzerland 2011

Federal elections were held in Switzerland on October 23, 2011. All 200 members of the National Council and all 46 members of the Council of States were up for reelection. Together, these two chambers make up the Federal Assembly, Switzerland’s federal legislature. The Federal Assembly together elects the seven members of Switzerland’s government, the Federal Council. Swiss elections can’t see a government being “defeated” and replaced by another, because since 1959 Switzerland’s government has had the same make-up or close to it. I had covered the structure of Switzerland’s semi-direct consociational government structure as well as all the parties in a preview post here.

It doesn’t actually matter much in terms of realities of governance, but since 1991 Swiss politics have really been turned on its head as the hegemony of the ‘moderate’ forces: Socialists, liberals and Christian democrats was challenged by the upstart right-wing populist SVP which has gone from 11.9% support in 1991 to 28.9% in 2007, thus forcing the Christian democrats to lose a seat in the Federal Council in the SVP’s favour back in 2003. The SVP’s success stems from its ability to portray itself as a nationalist party which defends Swiss sovereignty, Swiss neutrality, Swiss interests and “real Swiss” people from the perceived dangers of internationalism, economic interventionism and above all ‘foreign criminals’ whose presence in Switzerland, they claim, threatens Swiss values and Swiss way of life. Obviously, the SVP is a very controversial party and its electoral ads have often been called xenophobic or racist. After the 2007 election, the SVP’s accession showed no signs of being checked: two SVP-led measures to ban minarets (2009) and to deport foreign criminals (2010) were approved by a majority of voters in referendums.

Turnout was 49.1%, which seems to be one of the highest turnouts since 1979 or something. This number, which seems low for voters in other countries, is pretty high for low-turnout Switzerland. The results for the National Council were as follows:

SVP-UDC 26.6% (-2.3%) winning 54 seats (-8)

SP-PS 18.7% (-0.8%) winning 46 seats (+3)

FDP.Liberals-PRL 15.1% (-2.6%) winning 30 seats (-5)

CVP-PDC 12.3% (-2.2%) winning 28 seats (-3)

Greens 8.4% (-1.2%) winning 15 seats (-5)

GLP-PEL 5.4% (+4%) winning 12 seats (+9)

BDP-PBD 5.4% (+5.4%) winning 9 seats (+9)

EVP-PEV 2% (-0.4%) winning 2 seats (nc)

EDU-UDF 1.3% (nc) winning 0 seats (-1)

Lega 0.8% (+0.2%) winning 2 seats (+1)

CSP-PCS 0.6% (+0.2%) winning 1 seat (nc)

PdAS-PST 0.5% (-0.2%) winning 0 seats (-1)

Sol 0.3% (-0.1%) winning 0 seats (nc)

SD-DS 0.2% (-0.3%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Others 2.3% (+0.5%) winning 1 seat (+1)

As expected, the results, at a glance, indicate remarkable political stability which is the norm, not the exception, in Switzerland (or at least was until the SVP turned it all on its head). The most significant result is that of the SVP, which has suffered its first major setback in over 20 years. The SVP’s vote had increased in all federal elections since 1991, but this year the party’s vote fell back by a statistically significant 2 percentage points. This is a pretty major setback for the SVP, which had really wanted to break the never-broken 30% barrier this year and was in a rather good position to do so throughout the last year or so. Part of the SVP’s decline comes from a larger than expected vote transfer between the SVP and the Bourgeois-Democrats (BDP), the moderate splinter of the SVP spearheaded by the SVP’s old moderate agrarian factions from Bern and Grisons. The BDP took away a large number of votes from the SVP in Grisons, where the BDP’s founding figure (federal councillor Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf) is from. The SVP’s vote fell 10% from 34.7% to 24.5%, while the BDP took 20.5%. The BDP had not, ironically, been predicted to hurt the SVP all that much but we apparently underestimated the size of the remnants of the moderate agrarian SVP in the party’s modern electorate. Another explanation for the SVP’s setback might be that it has hit the ceiling and, given how controversial and polarizing it is, it will struggle to go any higher than 29% or so. To my knowledge, the SVP has never consistently polled over 30% federally. Finally, the economy (which, this being Switzerland, is doing pretty well) and a high Swiss franc (and thus inflation) was an important issue in this campaign. The SVP’s strength with voters is not on economic issues (where the Socialists or Radicals play better) but rather on asylum/immigration/nationality issues which were big in 2007 but not as big this year. Despite the SVP’s setback, 26.6% is still a high mark for any party in Switzerland and this only places the SVP back at its 2003 levels, which were already pretty good for the party.

The SVP (UDC) was not the biggest party in any French-majority canton this year, unlike in 2007 when the party had topped the poll with 21-22% in Vaud and Geneva. The party’s vote generally held better in the French cantons, because the BDP is inexistent there, but the vote for the other two major parties in those areas – Socialists and Radical-Liberals – coalesced better this year. The party, finally, broke through on its own in Ticino, the Italian-majority canton where the SVP’s rise thus far had been checked by the regionalist right-wing Lega. Despite the Lega doing very well this year (17.5%, up from 14% in 2007), the SVP also managed to increase its support by 1% (8.7% to 9.7%) and win its first seat ever in the canton which had until now been the SVP’s only weak spot.

The Socialists suffered another setback, winning 18.7% which is their lowest vote share since 1919. But the SP gained 3 seats. The SP was unable to benefit from the issue of the high Swiss franc and rising inflation, which should have helped the party. The SP gained in strength in Geneva, Vaud and Fribourg but generally lost votes elsewhere. In Fribourg, the SP’s win marked the first time this Catholic Sonderbund canton had not voted for the CVP and the second time since 1919 that any Sonderbund canton has voted Socialist. But the SP lost Neuchâtel for the first time since 1919.

The FDP’s merger with the Liberals (1.9% in 2007) wasn’t enough to right the sinking ship. The new FDP-Liberal outfit won 15.1%, the worst result for the Swiss radical-liberal movement since 1919 and a result which is even below that of the FDP alone in 2007. In Ticino, the FDP’s leader, Fulvio Pelli, did not even win reelection. In part, the FDP was one of the victims of the new BDP, which took more voters from the centrist parties than from the SVP. In Bern, where the BDP polled 15%, the FDP’s vote fell from 15% to 8.7% this year. The success of the Green Liberals, whose electorate overlaps with that of the FDP in large part, also hurt the party. The new FDP-Liberal party polled better than the FDP alone in Romandie, the Liberal Party’s base, but in Geneva and Vaud the showing of the FDP, while not insignificant, falls quite a bit below that of the combined 2007 vote of the FDP and Liberals – and this is in cantons where the BDP is inexistent and even the Green Liberals pretty weak (3% in Geneva, 5% in Vaud). Only in Neuchâtel, where the Socialist dominance since 1919 had a lot to do with the division of the bourgeois vote between Liberals and FDP (PRD), did the Liberal vote fold neatly into the FDP vote – both parties had polled 13% each in 2007, and this year they won 26.9%. It also helps that the Green Liberals didn’t run and the BDP only won 1.5%…

The CVP also broke the record for worst electoral performance since 1919 with a paltry 12%. The electoral decrepitude of the radicals and the Catholics is striking, when you consider that these two movements are the oldest political movements in Switzerland. The CVP did poorly pretty much everywhere, losing Fribourg for the first time since 1919 and winning less than 40% in Valais. It benefited from the absence of a Christian-social list in Jura, a list which had won 11% in 2007 but did not run this year, allowing the Christian democrats to regain a traditionally Christian democratic canton. Like the FDP, the CVP was one of the ‘centrist victims’ of the BDP and the Green Liberals’ success. The CSP, which lost its seat in Fribourg, did gain a seat in Obwald where the CSP’s Karl Vogler (apparently endorsed by the CVP) won 57% against 43% for the SVP incumbent (Obwald elects only one member). Vogler will apparently sit with the CVP, whereas the CSP until now sat with the Greens. The Protestant EVP held both of its seats but saw its support dip a bit. The ‘christian right’ EDU lost its only member.

The historic low hit by both the FDP and CVP, two of the old hegemonic parties in Swiss politics, puts into question their long-term survival. These two parties haven’t gained votes in any election since 1979 and keep hitting new “historical lows” in every election since the 1990s. If the BDP and Green Liberals keep showing vitality in coming years and the SVP doesn’t collapse and burn back to the 11% it used to win, then the very survival of the FDP and CVP are clearly on the line. Neither of these parties seem to be capable of “reinventing” themselves in the current political structure, and this being Switzerland, “reinventing” a party is rather tough when you’re a governing party since the 1890s… For now, the FDP and CVP can keep whistling past the cemetery because their immediate fate isn’t on the line and they’ll still be key governing parties in the short-term perspective.

The Greens did badly. They too had hoped for a breakthrough, that is breaking 10%. But the Greens were hurt more than originally expected by the success of the Green Liberals, who won 5.4% and 12 seats (up 9). The Greens need to move towards the centre if they want to regain support they lost and be in a position to cut short the GLP’s success. Still, this is the second highest result for the Greens in any election and, on the upside for them, they gained support (albeit not much) in the cantons where they ran and where the GLP did not run. The Greens are still in contention, in the long term, to out poll one of the two dying centrist parties and place fourth.

The two winners of this election were the Green Liberals, who won 5.4% and 12 seats, up 9 seats and 4% from 2007; and the Bourgeois-Democrats (BDP), who won 5.4% and 9 seats – up from 5 members before the election. The Green Liberals and BDP both gained votes primarily from the FDP and CVP but also, this was surprising, from the Greens (in the GLP’s case) and the SVP (in the BDP’s case). The GLP did best in German Switzerland, which is where the party’s base is. It won 11.5% in Zurich (out polling the Greens), and its states councillor from Zurich Verena Diener is in good position to win the runoff. The GLP won roughly 5-6% in the other German cantons where they ran (save 8% in Grisons) and between 3 and 5% in the French cantons where they ran (5% in Vaud, 3-3.5% in Geneva and Fribourg). The BDP did best in Grisons, Bern and Glarus (20.5%, 14.9% and 61.7% respectively) which is where the BDP took the most members from the local SVP branches and where they had sitting members. It also won 6% in Aargau and Basel-Landschaft and 5% in Zurich. In general, however, outside their strongholds, the BDP did pretty poorly (3-5%) and isn’t really in a favourable long-term position, except if the FDP dies off quickly. The BDP won between 0.6% and 1.9% in the French cantons where they ran.

The far-left finds itself with no seats for the first time in its history. They lost their last sitting member in Vaud, where they won 3.9%. They polled 10% in Neuchâtel and 6.5% in Geneva.

A word also on the other success story of this election: the right-wing populist/regionalist Geneva Citizens Movement (MCG), which I had mentioned in my preview post for their success (14%) in the 2009 cantonal elections in Geneva. The MCG, which, similarly to the SVP, is a “politically incorrect” party, has made the battle against foreign workers from France and Italy their cause. The MCG won roughly 11.7% in Geneva and one seat. But their attempts to expand into Vaud as the Mouvement des citoyens romands (MCR) didn’t work out: only 1.2% in Vaud.

A quick word on the Council of States: there will be a very high number of runoffs. I’ve counted 19 seats still left to be assigned in runoffs, notably in the cantons of Zurich, Vaud, Valais, Uri, Ticino, Bern and Lucerne were both seats are up for grabs. So far, the SP has 8 seats, the FDP and CVP 7 seats each, the SVP 4 seats and the Greens one seat. At dissolution, the CVP held 15 seats, the FDP 12, the SP 9, the SVP 6, the Greens 2 and the GLP 2. The full results by canton, which I won’t run through, can be found here. In Zurich, which I think was the most interesting contest, the GLP and FDP incumbents have placed ahead of the pack. Christoph Blocher, the SVP’s controversial figure, placed in third and is unlikely to win in the runoff.

In the preview post, I had talked about the Federal Council’s renewal in December. The comments made then still apply, and nothing has really changed for any party. The SVP might be in a slightly weaker position to claim a second seat, but it is still very much in contention. The FDP’s second seat might be slightly more at risk, but the CVP after its paltry showing on Sunday isn’t in a good position to claim a second seat at the FDP’s expense. The Greens have no chance at a seat. The big question remains whether or not the BDP’s Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf will win reelection. Her situation has not changed much with the election, because it is obviously not enough to have the BDP’s small caucus behind you. She needs the votes of the CVP and SP if she is to win.

Election Preview: Switzerland 2011

Federal elections will be held in Switzerland on October 23, 2011. Beyond Switzerland, October 23 will be a pretty fascinating superwahltag with some great elections in Tunisia, Argentina and Bulgaria. In Switzerland, all 200 members of the National Council (the lower house) and all 46 members of the Council of States (the upper house) are up for reelection.

The Swiss Federal Political System

Switzerland’s unique variant of representative liberal democracy sets it apart from its European neighbors and indeed in the entire world. Switzerland is a federal state modeled around the United States, but two elements make it unique: its form of semi-direct democracy in which voters play a much more influent and powerful role in everyday politics, and its consociational model of governance (shared with Northern Ireland these days). As a semi-direct democracy, Swiss voters can force a referendum on any legislation passed by a legislature and through popular initiatives can amend the constitution.

Federal legislative power in Switzerland is vested in the bicameral Federal Assembly, which is made up of two houses with equal powers. The National Council, like the U.S. House of Representatives represents cantons proportionally to their population (to a certain extent). The Council of States, like the U.S. Senate represents cantons equally (or close to it). In the National Council, each one of Switzerland’s 26 cantons is guaranteed at least one member and additional members based on its population. Like the American House, the number of members is now capped at 200. The most populated canton, Zurich, elects 34 member. There are, roughly 36,000 voters for each member. Appenzell Innerrhoden, Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Glarus, Nidwald and Obwald elect only one member. In the Council of States, the 20 full cantons elects two members. The old half-cantons (usually cantons which have been split in half) of Obwald, Nidwal, Basel-Landschaft, Basel-Stadt, Appenzell Innerrhoden and Appenzell Ausserrhoden elect only one councillor.

In the National Council, those small cantons electing only member use a pretty straight-forward FPTP (‘majoritarian’) system. In the cantons of Uri, Glarus and both Appenzells, the vote is open ended in that the voter may write in any candidate of his choice. In the other cantons electing only one members, there is a candidacy deadline. The other cantons which elect two or more members use proportional representation, which certainly isn’t as straightforward. In a typical ‘big’ canton, each party usually presents its list of candidates – usually one name for every seat, but some parties like to run the same person for more than one seat to capitalize on their chances of election (or not run candidates for every seat). But beyond that, in a lot of cases, the major parties usually have more than one list: for example, in a lot of cantons, you find a “Party X” list but also “Party X – Youth Section” list. Different party lists may then coalesce together (apparentements) to be counted as a single list when votes are counted. Within the apparentements, there can be sous-apparentements where the lists of the same party unite to increase their individual chances of obtaining seats within a wider coalesced list. The CiviCampus website, available in the four official languages, has an animation of how voting works in the proportional system.

Party lists are open lists. Prior to the election, each voter is sent pre-printed party lists with the names of all candidates on the party’s list. The voter has a whole array of possibilities. He/she can deposit this pre-printed ballot as is in the provided envelope, and each candidate on the list will receive one vote and the party as a whole will receive as many votes as there are open seats (example: in a 5-seat canton, there are 5 candidates: if the list is not modified, each candidate gets one 1 vote and the party overall gets a sum of 5 votes). The voter can also strike out a candidate’s name: the candidate will not receive an individual vote, but the party itself will receive an ‘at-large’ party vote. A voter can also strike out a candidate’s name on the list and replace that candidate with another of the candidates on the same list (cumuler in French): that candidate would thus get an extra vote out of that ballot while another candidate would receive no votes. A voter, however, may not make his ballot so that a candidate gets more than two individual votes. Panachage is also allowed, meaning that a voter can strike out a candidate and replace him/her with a candidate from another list: thus the candidate’s votes will be shared between two or more parties overall. A voter may also strike out names, panacher and cumuler all at once! Voters also receive, prior to the election, a blank ballot. The voter may write a party’s name and at least one candidate’s name on it (from any party) – if a voter has 5 votes in the 5-seat canton, he/she can write the names of, say, 3 candidates – each candidate will get one vote and the remaining two votes the voter has are given to the party at-large. If the voter writes only the names of candidates on the blank ballot but no party, if he/she does not use up all 5 votes then he/she would not use all votes. The website mentioned also explains how the elections officials may correct certain ballots with minor errors. Specific rules do vary from canton to canton.

The Council of States is generally elected alongside the National Council, and usually elected through majority votes. In general, a candidate needs an absolute majority to win or a runoff is organized 3-5 weeks later depending on cantonal law. The canton of Jura, and, starting this year, Neuchâtel, elect their members through proportional representation. The canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden elects its sole member in a popular assembly (the Landsgemeinde, one of the last remaining vestiges of direct democracy) prior to the election. This year, the canton of Nidwald elected its sole member unopposed. Specific electoral laws and regulations vary from canton to canton. Because of the different electoral system which favours parties with a larger ‘vote potential’, the Council of States has tended to see small parties (outside government) and the two most ‘extreme’ governing parties (SP and SVP) being weaker than in the National Council at the benefit of the centrist parties.

The federal executive is formed by the Federal Council. The Federal Council has seven members, elected individually by the Federal Assembly. Each member is responsible for a specific cabinet department dealing with a policy area which falls within the federal government’s jurisdiction. One member is also elected for the ceremonial revolving one-year office of President of the Confederation. The Federal Council is run by the principle of collegiality, thus besides the largely ceremonial President there is no “Prime Minister” or leading head of government. The other principle which has truly defined Swiss politics is the “magic formula”, in use since 1959 and modified in 2003. The “magic formula” guarantees for the proportional representation of the four main political forces in Switzerland. Between 1959 and 2003, the Socialists, Radicals and Christian Democrats held two seats each with the final seat going to the agrarians (SVP). In 2003, the Christian Democrats lost a seat to the SVP.

Unlike in other liberal democracies, majority rule is not the overarching principle here. Rather, the overarching principle in Swiss politics is concordance or compromise. The vast cultural, linguistic, religious and economic differences which exist in Switzerland have played a role in compelling political actors to adopt this style of consociationalism. All four “governing parties” seek common ground over some sort of compromise in all legislation, both to satisfy all political parties involved but also protect against potential popular rejection through referendum by satisfying social actors and wider networks. The “magic formula”, which, as we’ll explore is increasingly compromised these days, has nonetheless given Switzerland half a century of remarkable political stability, built national unity and protected Swiss democracy from the temporary irrationality of voters. However, the whole system being built on the bases of concordance has not encouraged vibrant political debate and turned most governing parties into boring centrist parties. Parties’ ideological markers are increasingly unclear, and Swiss politics is marked by remarkable political immobility. Furthermore, for all the talk of the “vibrancy” of Swiss democracy because of referendums and semi-direct democracy, Switzerland has some of the lowest voter turnouts in Europe. There is both an “election overload” and a general perception that nothing really changes and that voting is useless. Less than half of eligible voters actually consistently participate in Swiss democracy.

The powers of the legislature to pass laws is subject to popular control, a unique type of “checks and balances” with the people being a level of government to itself. 50,000 citizens or 8 cantons can force a referendum on any bill passed in the last 100 days. Between 1874 and 1997, only about 7% of the laws actually were subjected to a referendum, and about half of those where ratified by voters. The threat of a referendum has an indirect effect on the legislative process, pressuring the government and political actors to reach compromise to prevent a referendum. Conservatives also appreciate the referendum option as a bulwark against anything which goes to far in their eyes. 100,000 citizens may also draft a constitutional amendment (popular initiative) and force a referendum on it. Again, while only a tiny handful out of the hundreds of initiatives have been approved, they are also an indirect effect on the legislative process in that they bring to political limelight issues which were until then not in the realm of political debate.

Evolution of the % vote for the 'big four' and the Greens, 1919-2007 (1939 excluded)

Swiss Political Parties and Ideologies

Swiss political parties are organized firstly on a cantonal basis, an impact of Swiss federalism. Though parties have been increasingly centralized and homogenized in recent years, Swiss parties are both less centralized and less professionalized than other European party systems. Cantonal sections remain the bedrock of the parties themselves and the cantonal sections are independent entities. In the past, cantonal sections have taken positions or acted in a way which was rather out of sync with the federal party. Cantonal sections often take the role of factions in other European party systems: a certain cantonal section may be ideologically different from the federal party, and they often are the bases for party splits. For example, the Liberal Party and the Free Democrats (Radicals) merged in 2009, but the Liberals and Radicals in Geneva merged only in 2011 and in Basel-Stadt the two parties remain separate from one another. Because politics is really played at a cantonal level, there is no dominant party boss as in other countries and only a few party leaders have a national image, often because of their strong individual personality. Party leaders are, on the whole, pretty unimportant or certainly not as important as in other European countries.

Switzerland emerged as a federal country with a central government worthy of its name only in 1848. Besides an ill-fated attempt at centralization imposed by the French in the form of the Helvetic Republic, Switzerland until 1848 was a confederation of independent states (cantons) which were linked much more by individual treaties rather than by the very weak central government. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the European powers recognized Switzerland’s neutrality and encouraged the reconstruction of independent Switzerland upon confederal lines. The Federal Pact of 1815 did not create a state, but rather a confederation of cantons with their own laws, currencies, tariff systems, militias, policy spheres and political systems (Neuchâtel was a Prussian-ruled monarchy, a few cantons were direct democraties, others were limited democraties, others were aristocratic republics). Certainly the cantons didn’t kill each other anymore, but the central government had very little power – think Articles of Confederation in the United States. By the 1830s, the liberal ideas of political equality, universal suffrage, political and economic freedoms and anti-clericalism gained a foothold in the liberal Protestant cantons. Individual cantons, starting with Ticino (ironically a Catholic canton), “regenerated” their constitutions but attempts to reform the Federal Pact failed throughout the 1830s. Original attempts at reform had not been marked by sectarianism, but the anti-clerical mood of the 1840s fired up sectarian tensions between the Catholic and Protestant cantons. Liberals were progressively replaced by the more left-wing radicals, who were stridently anti-clerical and largely Protestant. In reaction to mounting tensions between radical Protestants and conservative Catholics, seven Catholic cantons (Lucerne, Uri, the two Unterwald half-cantons, Schwyz, Zug, Fribourg and Valais) formed the Sonderbund Pact in 1845 as a defensive pact against the mounting influence of the radicals.

By 1846, the radicals had gained power in a majority of cantons and through the Federal Diet they were in measure to pass a string of resolutions banning the Sonderbund pact, calling for a type of constituent assembly and expelling Jesuit orders from the country. In November 1847, tensions boiled over into civil war between the Catholic Sonderbund and the federal state. The Sonderbund rapidly defeated, and the radicals in full control, a new federal constitution was adopted in 1848, under radical guidance, creating the modern Swiss federal state. The cantons lost their autonomy in matters such as customs duties or external trade, while power was centralized (comparatively speaking) in the hands of the federal government. New constitutions were introduced in 1874 and 1999.

2007 election results

SVP-UDC 28.9% (+2.2%) winning 62 seats (+7) and 7 state councillors (-1)

SP-PS 19.5% (-3.8%) winning 43 seats (-9) and 9 state councillors (nc)

FDP-PRD 15.8% (-1.6%) winning 31 seats (-5) and 12 state councillors (-2)

CVP-PDC 14.5% (+0.1) winning 31 seats (+3) and 15 state councillors (nc)

GPS-PES 9.6% (+2.2%) winning 20 seats (+6) and 2 state councillors (+2)

PEV 2.4% (+0.2%) winning 2 seats (-1)

LPS-PLS 1.9% (-0.3%) winning 4 seats (nc)

glp-pel 1.4% (+1.4%) winning 2 seats (+2) and 1 state councillor (+1)

EDU-UDF 1.3% (nc) winning 1 seat (-1)

PST 0.7% (nc) winning 1 seat (-1)

Lega 0.6% (+0.2%) winning 1 seat (nc)

PCS-CSP 0.4% (+0.1%) winning 1 seat (nc)

The Swiss People’s Party (SVP or UDC) is Switzerland’s largest party and also the most controversial party. The SVP finds its roots in the post-World War I agrarian movement in German Switzerland which split off from the Radicals in Bern in 1917 to create the first agrarian party, which became the Party of Farmers, Artisans and Independents in 1936. In 1971, the agrarian party merged with two cantonal sections of the small Democratic Party, a social-liberal party, to form the SVP. The Swiss agrarian movement has always been on the right of the Swiss political spectrum, having vocally expressed anti-socialist and nationalist sentiments since its foundation in 1917. A member of the bourgeois bloc, the SVP and its agrarian predecessor were the smallest member of this bloc and the smallest party in the Federal Council, with one member between 1930 and 2003. Between the mid-1930s and 1991, the SVP won roughly 11% of the vote. However, starting in the 1980s the SVP came under the influence of the Zurich section, led by the right-wing populist entrepreneur Christoph Blocher who moved the party to the right with emphasis on increasingly popular issues such as asylum, EU membership and Swiss neutrality. The impact of the SVP’s move to the right under the influence of the Zurich section was immediate and successful. In 1995, the party won 15%. In 1999, it became the largest party with 23% and scoring a record-high gain in vote. In 2003 and 2007, it again improved its showing to 27% and 29% – some of the strongest showings for a single party in the fragmented political landscape of Switzerland. The SVP’s first victims were smaller far-right parties such as the Swiss Democrats or the Freedom Party, but in recent years the traditional parties of the centre (Radicals and Christian Democrats) have both suffered. These parties centre-right voters punished them for their perceived shift to the left and their shift towards internationalist (pro-European integration) positions. The party has generally been at the centre of most political controversies in Switzerland. In 2007, its “kick out the black sheep” poster made international headlines. Its campaigns for the deportation of ‘foreign criminals’ and the ban on minarets opened it to accusations of racism and xenophobia. The SVP rather claims it fights for an independent and neutral Switzerland, against crime and against high taxes.

The SVP’s unchecked growth forced a revision of the “magic formula” in place since 1959 in 2003. The SVP’s Blocher, one of Switzerland’s most controversial politicians, was elected to the Federal Council in 2003 at the expense of the Christian Democrats. However, in 2007, the other parties in the Federal Assembly preferred to elect Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf of the moderate Grisons branch. When the SVP expelled the whole Grisons branch in 2008, a sign of the growing centralization of the SVP under the right-wing Zurich section and Blocher, the SVP was left with no seats in the Federal Council (the SVP’s other councillor, Samuel Schmid of the centrist Bern section, joined the dissidents). The SVP regained a seat on the Federal Council in 2009 when Schmid retired and was replaced by the SVP’s Ueli Maurer. The SVP claims that it is entitled to a second seat in government.

The agrarians were founded in German Switzerland and found most of its support in predominantly German Protestant cantons such as Bern. Traditionally weak in French Switzerland (Romandie), the SVP’s rapid growth since 1991 has also affected French Switzerland where the SVP (known in French as UDC) became the largest party in the cantons of Vaud and Geneva (but only with 22% or so). Only in Italophone Ticino has the SVP been unable to build a base – largely because of the competition of a quasi-identical regional party.

The SVP’s slogan this year is basically Swiss people vote SVP, a delightfully amusing statement which means that those who don’t vote SVP aren’t Swiss.

The Socialist Party (SP or PS) is Switzerland’s second largest party. The SP was founded in 1888 and has usually been Switzerland’s largest party, between the 1930s and the 1980s and for a stretch in the 1990s. Despite the SP’s growth in the interwar era, the fear of socialism in the wake of the 1918 general strike led the bourgeois parties to move closer together and exclude the SP from government until Ernst Nobs became the first SP federal councillor in 1943. During this time, the SP slowly abandoned its Marxist theses and progressively moderated its positions. Even when the party temporarily left government between 1955 and 1959, the SP kept its commitment to democratic ideals and its very anticommunist positions of the Cold War era. But the SP has struggled in the post-war era, split between a moderate (right-wing) faction and another pressuring the party to move closer to new social and political movements on the left. In the 1970s, a tack to the left (denouncing capitalism) helped it a bit but it fell badly in the 1980s. The relative proximity of the SP to new movements on its left or the desire to limit the growth of left-wing opponents such as the Greens might explain why the Socialists have taken a rather ‘green’ line on environmental issues or moved towards very pro-European positions. This hasn’t prevented internal dissensions and cantonal splits, or kept the party from falling into the contemporary trap of European social democratic parties, that is, a general lack of ideas besides being the largest anti-SVP party. Nonetheless, the SP has played a rather important role in the development of the Swiss welfare state and its political moderation guaranteed the success of the “magic formula” after 1959.

The SP has usually been stronger in French Switzerland than German Switzerland, and it performs best in Protestant areas – given that Catholic working-class voters have traditionally been well integrated into the Christian Democratic Party. But beyond this, the SP is a very urban party, in cities such as Zurich, Bern or Basel. The SP has been the largest party in all elections since 1919 in the canton of Neuchâtel, where the SP has a solid working-class base in the watchmaking centres of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle. Other bases outside urban areas include Solothurn, Schaffhausen and Glarus.

The SP’s slogan this year is something like for everyone, not for a few which is a boring empty political catchphrase which ought to be shunned.

The FDP.The Liberals (in French, PLR.Les Libéraux-Radicaux) is not Switzerland’s dominant party any longer, but it has had the most profound influence on Switzerland since 1848 of all parties. The Radicals, as they are known in French (they are rather known as ‘liberals’ in German), are the heirs of the political radicals of the 1830s who spearheaded the transformation of Switzerland from a confederation to a federal state by 1848. The Radicals drafted the 1848 and 1874 Constitutions, and, excluding their conservative Catholic rivals, they were the hegemonic party at all levels of the federal government during the nineteenth century (post-1848). Between 1848 and 1891, they held all seven seats in the Federal Council. They retained their majority in the Federal Council until 1943. Until the introduction of proportional representation in elections to the National Council in 1919, the Radicals were also the dominant party in the legislature. The radicals formed a political party in 1894, with the foundation of the FDP (PRD in French). The central role of the Radicals was somewhat lost with the introduction of PR in 1919 and the party’s place as a catch-all broker was weakened with the loss of the party’s left-wing working-class faction to the SP and the loss of the party’s right-wing rural faction to the agrarians. However, it remained one of Switzerland’s top two parties up until the SVP’s eruption into the political landscape in the 1990s; and the Radicals played a major role alongside the SP in the development of Switzerland’s post-war welfare state model and the success of the “magic formula”.

Ideologically, the growth of the SP in the interwar era pushed the Radicals closer to their former enemies (the conservatives) to form a bourgeois anti-socialist bloc which definitely aligned the Radicals with the centre-right. After taking a stridently neoliberal position starting in 1979, which temporarily stopped their decline, the Radicals have since moved back towards the centre though retaining economically liberal positions: tax cuts, deregulation, welfare reforms and a minimal state. Of the four major parties, the Radicals are pretty much the second most right-wing party after the SVP and they have tended to be the closest to the SVP of the three non-SVP governing parties. Yet, the Radicals are more internationalist and liberal than the isolationist conservative SVP.

In 2009, the FDP merged with the smaller Liberal Party (LPS). The Liberals, the right-wing faction of the broader Swiss radical-liberal movement, were founded in the 1890s and were a small liberal group to the right of the Radicals and generally dominant in French Protestant cantons such as Geneva or Vaud. The Liberals generally took more stridently free-market positions than the FDP while the FDP was embracing the social market economy, and in their early days they generally opposed the more radical ideas of the Radicals preferring, for example, limited censitary suffrage to universal suffrage. The Radicals were in turn opposed to their left by the social-liberal Democratic Party, more working-class rather than urban bourgeois in its support, and critical in the early days of the Radical’s machine control over politics. In the twenty-first century, the progressive weakening of both the Liberals and the FDP with the rapid growth of the SVP forced the two parties to move past historical differences to form a common party, known as the FDP.The Liberals in German and English. The Liberals won a record-low 1.8% in 2007, while the FDP has been in constant decline since 1979 from 24% to 16%.

The radical movement was born in the Protestant cantons of Switzerland the Protestant cantons, both German and French, have remained the base of the Radical Party for most of its existence – although this is certainly not a universal rule. For example, the Radicals have always held Uri’s sole seat in the National Council despite Uri being a Catholic Sonderbund canton.

The FDP’s slogan is out of love for Switzerland. How sweet.

The Christian Democratic People’s Party (CVP or PDC) is the political heir of the old conservative Catholic movement in Switzerland, historically the arch-rivals of the radical (Protestant) movement. The conservatives defended a traditional vision of a conservative, rural and decentralized federal Switzerland with a strong role for the Catholic Church, in contrast to the radicals whose vision was that of a modern, democratic and secular centralized Switzerland with the ‘reactionary’ Catholic Church shunned and shut out of power. The radical vision carried the day over the Catholic minority, and the Catholic conservatives found themselves shut out from power starting in 1848 and until at least 1891. But they remained a powerful opposition to the radical hegemony, with their base in the Sonderbund cantons of central Switzerland. In 1891, Joseph Zemp became the first non-radical member of the Federal Council and the Popular Conservative Party (as it was then known) gained a second seat in government in 1919 following the first proportional elections to the National Council. With a steady electorate (because of the solidness of the Catholic bloc vote) oscillating between 21 and 23%, the CVP (the name adopted by 1970) has been in constant decline since 1979 – from 22% to 14%. The CVP’s decline forced it to abandon its second seat in the Federal Council to the SVP, a second seat which the CVP currently disputes with the FDP. The CVP has lost a lot of votes to the SVP, which has really broken religious divides to appeal to equally conservative, rural, German Catholic voters in old CVP strongholds such as Schwyz, Unterwald or Zug.

As a Catholic party, the CVP has its base in the old Sonderbund cantons – in central Switzerland (except Uri, at the federal level) but also Valais, Fribourg, Jura and Appenzell Innerrhoden. In the cantons with a strong Catholic minority – Solothurn, Aargau, Saint-Gallen and Grisons – the CVP has always had a smaller minority position with Catholic voters. The CVP tried to expand its base in the 1960s, but despite this the CVP map pretty closely follows the map of Catholics in Switzerland and it performs very poorly in cantons with few Catholics. Similar to other Catholic parties in Europe, the CVP was quite a mass-party with a wide base of Catholic farmers, traders and workers. Working-class Catholics have been well integrated into Catholic unions and the CVP, which has struggled with a long opposition between conservatives/centrists and the Christian-social movement, more left-wing on economic issues. The former has generally dominated, but the CVP retains a significant Christian-social base outside Jura and Fribourg. This explains the CVP’s more interventionist (or ‘humanist’) economic policies, favouring ‘pro-family’ policies and the social market welfare policies. It is also pro-environment.

The CVP’s slogans rock: Success. Switzerland. SVP or the best – No Switzerland without us.

The Green Party of Switzerland (GPS or PES) is Switzerland’s largest opposition party. The Greens appeared in the mid-to-late 1970s, and gradually united different cantonal sections to create a nationally structured party. Originally starting out on the gauche de la gauche, the Greens – especially in German Switzerland where their growth was slower – were hurt by competition from other parties such as the green/social-liberal Alliance of Independents (LdU) or the New Leftish Progressive Organizations of Switzerland (POCH). In 1987, the Greens, buoyed by events such as Chernobyl, won 9 seats and 5.2% of vote. After a trough in the 1990s, the Greens have started creeping up on the back of the ‘big four’ winning 9.6% in the 2007 elections. In the long term, the Greens could definitely threaten the hegemonic positions of the ‘big four’ governing parties. Their growth in recent years throws the long-term stability of the “magic formula” into doubt because, if they keep gaining strength, the Greens will have a very strong claim to a seat in the Federal Council especially if the old parties like the FDP or CVP keep falling apart.

The Swiss Greens are rather left-wing and ‘deep green’ in their political orientation. They want out of nuclear energy ASAP – Switzerland will be progressively withdrawing from nuclear energy in the wake of the Fukushima incident. It wants the country to cut its CO2 emissions by 30%, a “green economy” and it favours a very liberal immigration policy and a very pro-European internationalist foreign policy. In this regards, staunchly left-wing, environmentalist and socially liberal it is the arch-rival of the SVP – the two hate each other with a passion. The Greens, however, have had troubles hesitating between a centrist orientation and a very left-wing orientation. In some cantons such as Bern or Basel-Stadt, there are in fact two cantonal sections which each represent one of these factions. As we’ll see, the division of the Greens could put a stop to their ambitions to overtake one of the ‘big four’ parties.

The Greens are, shockingly, a urban party. It does very well in the liberal French cantons of Geneva (16.4%) and Vaud (14.3%). In Zug, the Greens’ local referent, the Alternative-The Greens Zug, also has a surprisingly strong base: 17% in 2007.

Political positioning of all 200 deputies (source: Swiss government)