Category Archives: Latvia

EU 2014: Latvia to the Netherlands

The next installment in our overview of the May 2014 EP elections in the European Union takes us to several small member-states but also the Netherlands.

Note to readers: I am aware of the terrible backlog, but covering the EP elections in 28 countries in detail takes a very long time. I will most likely cover, with significant delay, the results of recent/upcoming elections in Colombia (May 25-June 15), Ontario (June 12), Canadian federal by-elections (June 30), Indonesia (July 9), Slovenia (July 13) and additional elections which may have been missed. I still welcome any guest posts with open arms :) Thanks to all readers!

Latvia

Turnout: 30.24% (-23.45%)

MEPs: 8 (-1)

Electoral system: Semi-open list PR (votes for party lists, voters may add a ‘plus’ to candidates they like on the list and strike through candidates they don’t like; votes for candidates = party list votes – # of strikes through + # pluses; most popular candidates on the list are elected), 5% threshold (national constituency)

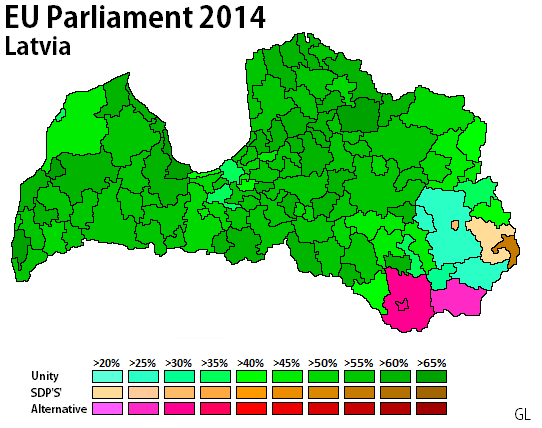

Unity (EPP) 46.19% (+11.36%) winning 4 seats (nc)

National Alliance (ECR) 14.25% (+3.99%) winning 1 seat (nc)

SDP’S’ (S&D) 13.04% (-6.53%) winning 1 seat (+1)

ZZS (EFD) 8.26% (+4.54%) winning 1 seat (+1)

LRS (G-EFA) 6.38% (-3.28%) winning 1 seat (nc)

Alternative (S&D) 3.73% (+3.73%) winning 0 seats (-1)

Latvijas Reģionu apvienība 2.49% (+2.49%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Latvian Development 2.12% (+2.12%) winning 0 seats (nc)

LSP (GUE/NGL) 1.54% (+1.54%) winning 0 seats (-1)

LSDSP (S&D) 0.33% (-3.46%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Others 0.89% winning 0 seats (-1)

Latvia’s ruling centre-right party, Unity, won a very large victory in an election largely marked by very low turnout (30.2%). Latvian politics since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 have been highly unstable, and, in recent years, marred by rising voter apathy or cynicism due to difficult economic conditions and the widespread perception that Latvian politics are controlled by corrupt oligarchs. Latvian politics – more so than in Estonia or Lithuania – are also highly polarized around the very contentious issue of Latvia’s large Russian minority.

Latvia was hit extremely hard by the economic crisis beginning in 2008, the result of a housing bubble and easy credit market in the Baltic states. Latvia, which was hit the hardest of the three states, had enjoyed three consecutive years of economic growth over 10% between 2005 and 2008, thanks to economic (and political) integration with the European market since liberalization in the 1990s and the associated inflow of foreign investment, mostly in the form of credit from foreign parent banks (often Scandinavian). Most investment was directed towards the non-tradable goods sectors (real estate, construction, financial services) and domestic banks in the Baltics borrowed heavily, in Euros, from parent banks abroad on very low interest rates and were thus able to offer low-interest mortgage loans to local home-buyers. Latvian house prices expanded, on the EC’s house price index, from below 75 in early 2005 to a peak at 195.45 in the first quarter of 2008, the highest level of the three Baltic states. The Latvian case was further aggravated by higher inflation (15.3% in 2008, the highest in the EU) and greater economic mismanagement by the government, which was unwilling to do much (until late in 2007, by restricting credit) to address a rapidly overheating economy. The Latvian economy began collapsing in the third quarter of 2008, and GDP growth fell to a catastrophic -17.7% in 2009. Unemployment skyrocketed from 5.6% in December 2007 to a high of 10.8% in 2010, housing prices collapsed, the deficit ballooned from 0.7% in 2007 to 9.2% in 2009 and the country’s public debt increased from only 9% of GDP in 2007 to 44.5% in 2010.

When the recession struck in 2008, Latvia was governed – as has always been the case since 1991 – by a coalition of largely right-wing and vaguely populist parties, at the time led by Prime Minister Ivars Godmanis and the Latvia’s First Party/Latvian Way (LPP/LC), an alliance of two (corrupt and populist) right-wing parties. The government was forced to ask the EU and IMF for a €7.5 billion bailout (the World Bank, Nordic countries and EBRD also provided funds) in December 2008, with a first installement released in February 2009. The country’s catastrophic economic state in 2009, as well as the government’s woeful mismanagement of the economy resulted in large anti-government protests in January 2009 and eventually forced Godmanis to resign from office in late February 2009, after junior allies in his cabinet pulled the plug. Valdis Dombrovskis, a finance minister from 2002 to 2004 and MEP for the centre-right New Era Party, became Prime Minister in a broad right-wing coalition government which excluded the LPP/LC. The new government quickly implemented very severe and painful austerity measures, including significant increases in the VAT and excise taxes and deep cuts in public spending, wages and pensions. The government’s austerity policies impressed the IMF and the EU, and were endorsed by voters in the 2010 elections, which saw Dombrovskis’ new pro-austerity centre-right party, Unity (a merger of three parties, including the New Era and the Civic Union, which had won the 2009 EP elections), win 33 out of 100 seats. The oligarchs’ bloc – the LPP/LC and the People’s Party (TP), won only 7.8% and lost 25 seats.

Since 2010, the economy is clearly recovering (if not already recovered). Growth returned in 2011, with 5.3% growth after a three-year recession, and the economy is expected to grow by 3.8% in 2014. Unemployment, which sat at over 20% at the peak of the crisis, has since fallen to about 11.5% and is projected to drop into the single digits in 2015. As a result of the government’s austerity measures, the deficit has been reduced to only 1% of GDP in 2014. As a result, Latvia became the latest country to join the Euro, on January 1.

In 2011, a major political crisis led to snap elections in September 2011 – less than a year after the last elections – and further changes to the party system. The crisis began when then-President Valdis Zatlers used his constitutional prerogative to dissolve the Parliament (Saeima) after it had refused to lift the parliamentary immunity of Ainārs Šlesers, an oligarch-politician (a former cabinet minister) and leader of the LPP/LC who was the target of a corruption probe. As a result of Zatlers’ decision to dissolve the Saeima, he unexpectedly lost his reelection bid a few days later (the President is indirectly elected by the Saeima) and Andris Bērziņš, a politician from the Union of Greens and Farmers (ZZS) – itself an ‘oligarchs’ party’ whose top figure is Aivars Lembergs, the mayor of the port city of Ventspils since 1988 and one of Latvia’s wealthiest persons, was elected in his stead. As per the constitution, voters ratified the presidential dissolution in a July referendum. Zatlers formed his own party, Zatlers Reform Party (ZRP), to contest the 2011 polls on an anti-corruption and anti-oligarchs platforms. Zatlers cited Aivars Lembergs (ZZS), Ainārs Šlesers (LPP/LC) and former Prime Minister Andris Šķēle (whose party, the TP, dissolved before the 2011 elections) as the three leading oligarchs in Latvian politics. His campaign put the spotlight on the influence of powerful oligarchs/businessmen in Latvian politics and the opacity of political financing in the country, which was the only EU member without per-vote public subsidies until 2010. In the 2011 elections, the ZRP placed second with 20.8% and 22 seats, against 18.8% and 20 seats for Prime Minister Dombrovskis’ Unity party. The oligarchic parties did poorly – the ZZS lost 9 seats (it won 12.2%) while Šlesers was unable to buy his way into the Saeima again, the LPP/LC losing all seats with 2.4% of the vote (the party dissolved later, but Šlesers has returned to politics). Dombrovskis remained Prime Minister in a coalition government made up of Unity, the ZRP, independents and the nationalist National Alliance.

The largest party in the Saeima is currently the Harmony Centre (SC), a left-wing alliance which represent Latvia’s substantial Russian minority. The Russian minority in Latvia has been an extremely contentious and polarizing political issue in the country since independence. Like the other Baltic states, Latvia was annexed – illegally, say the current Baltic governments and most of the West – by the Soviet Union in 1940 and remained under Soviet rule until independence in 1991. A small Russian minority (about 11% of the population) of Old Believers and pre-war Russian immigrants existed prior to 1941, but the Soviet regime encouraged or forced ethnic Russians (and Ukrainians, Belarusian etc) to move to Latvia, settling largely in the cities to work in industry. The Russian population stood at 34% and the ethnic Latvian population at only 52% in 1989. The Republic of Latvia, upon independence, considered itself to be the legal continuation of the interwar independent Latvia, and therefore restored a 1919 citizenship law which meant that those who had moved to Latvia after June 1940 (and their descendants) were not considered Latvian citizen (unless they were ethnic Latvians) – they were widely viewed as illegal immigrants. Instead, residents lacking Latvian or any other citizenship are legally recognized as Latvian non-citizens, a status which grants them rights similar to Latvian citizens (living and working in Latvia, visa-free travel in the Schengen area, access to social services, constitutional protections) but they lack the right to vote or hold public office (even at the local level). Russia has vocally protested several times, considering them as ‘stateless persons’, a charge denied by Latvia, and organizations such as the OECD and Amnesty International have also been critical of the non-citizens status.

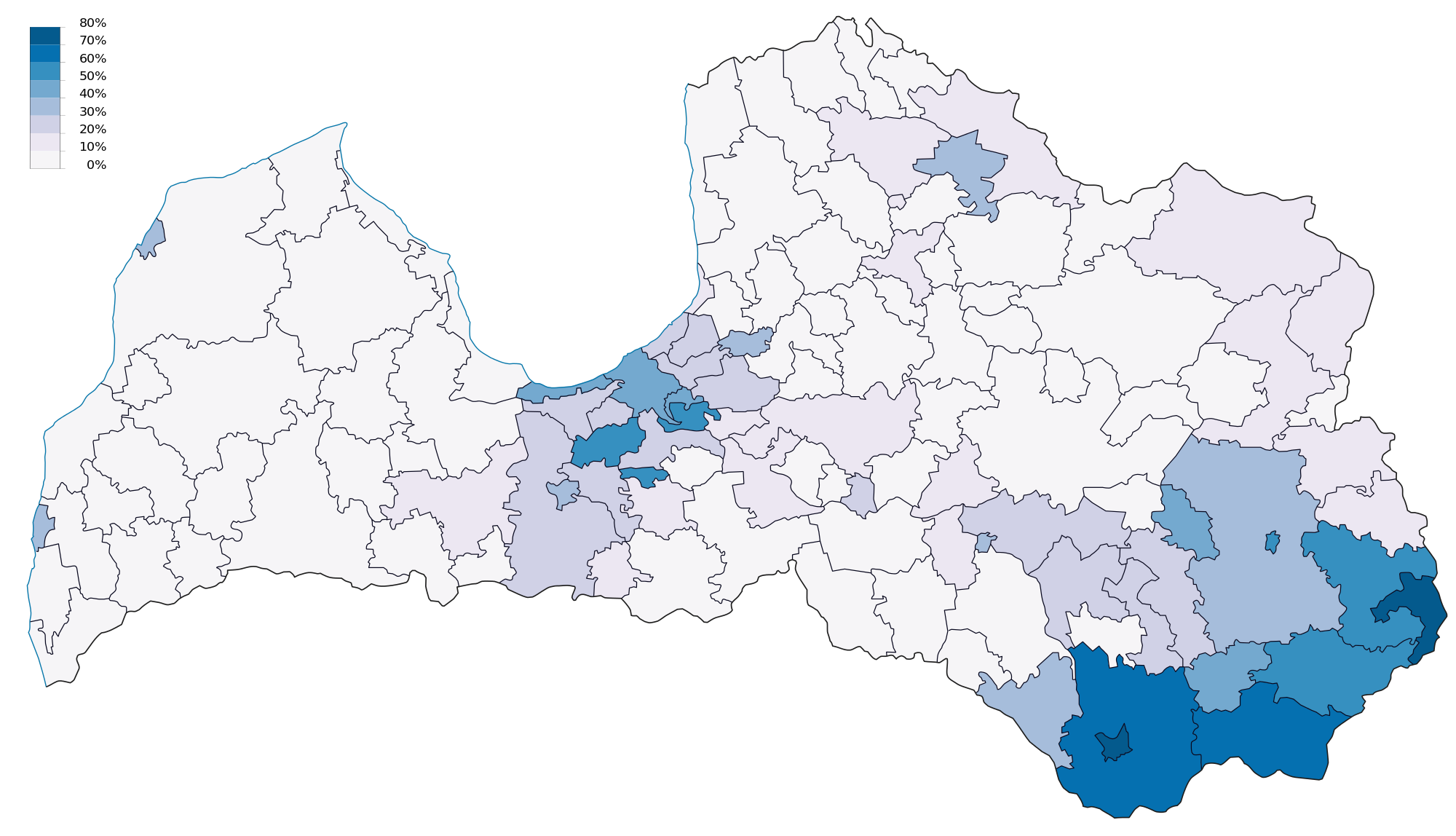

Today, according to the 2011 census, 62.1% of Latvian residents are ethnic Latvians and 26.9% are ethnic Russian, with smaller Russophone populations of Belarusian (3.3%), Ukrainians (2.2%) and Poles (2.2%). Since 1991, the Russian (and associated Belarusian and Ukrainian) population has decreased significantly (from 34% and 905.5k in 1989 to 586k in 2014). 33.8% of Latvians speak Russian most often at home, but only Latvian – the common language of 56.3% of the population – has official status. In 2012, a Russian group collected enough signatures to hold a referendum on the recognition of Russian as a co-official language, but the question was rejected by 74.8% of voters. The Russian population is largely concentrated in urban areas (notably in Riga, where they make up 40.2% against 46.3% of Latvians) and the poor eastern border region of Latgale, where 38.9% of the population is Russian (they make up a majority in Daugavpils city, which is less than 20% Latvian). According to the latest citizenship numbers (2014), there were over 282,000 Latvian non-citizens – or 13% of the resident population. 31.7% of Russians – and 51.9% of Belarusian and 52.3% of Ukrainians – are non-citizens, meaning (among other things) that they are not eligible to vote in Latvian elections. Compared to Russians in Estonia, there are less ‘non-citizens’ (38% of Estonian Russians have ‘undetermined citizenship’, although they have the right to vote in local elections) and while 21% of Estonian Russians are Russian citizens, only 7% of Latvian Russians hold a foreign (read: Russian) citizenship. The number of non-citizens has fallen considerably (from nearly a third of the population in 1991), due to naturalization and the access of children of non-citizens born after 1991 being eligible for citizenship fairly easily (since 2013, children born to non-citizens automatically gain citizenship if the parents wish). However, naturalization requirements are still quite stringent and may repel some: fluency in Latvian, knowledge of the basic principles of the Constitution, the national anthem and basic Latvian history and culture. However, since 1991, conditions for naturalization have been loosened significantly. For example, until 1998, there were strict windows limiting who could apply for citizenship when.

The Russian minority issue is a highly polarizing and politically-charged topic, as evidenced by the 2012 referendum. For many ethnic Latvians, the Baltic Russians are a symbol or reminder of the traumatic period of the Soviet occupation – an era associated not only with huge demographic changes, but also Stalinist terror, mass deportations and Russification policies. Therefore, the Russian minority bears the stigma of the Soviet occupation, and may be viewed by some ethnic Latvians as a ‘fifth column’ disloyal to the country. For example, the largest Russian party, SC, is accused of ties with Vladimir Putin’s United Russia and the SC – an alliance of parties – include unreconstructed communists. The Russian issue has a direct impact on Latvia’s political culture and party system. Because ‘the left’ is associated with communism and the Soviet Union, there is no strong ethnic Latvian left-wing party (the Russian minority parties, such as SC, are on the left, but attract little to no Latvian support) – even of a moderate, non-communist social democratic variant. Party politics are heavily conditioned by the Russian issue, with the Latvian majority voting for their parties and Russians voting for quasi-exclusively Russian parties, such as SC. No Russian minority party has ever been included in government, although there have been several attempts or talks to include SC in government. For now, the Russians’ positions on bilingualism and historical controversies (the recognition of the Soviet era as as ‘occupation’, which is not accepted by all Russians) bars them from government participation.

SC is the most successful Russian minority party in the young country’s history, and became the first such party to win the most votes in a national election (in 2011). SC leader Nils Ušakovs, an ethnic Russian, was elected mayor of Riga in 2009 and reelected in a landslide in 2013.

Prime Minister Valdis Dombrovskis resigned in November 2013, after the collapse of the roof of a Riga shopping centre killed 54 and injured 41, the worst disaster in six decades in the country. Dombrovskis took responsibility for the disaster, which was blamed on various factors including negligence and work safety violations by the private company and poor building inspection by the government. Some thought that Ušakovs should take responsibility, given the local government’s control over building quality, while others blamed the national government’s austerity budget cuts (which abolished the state building inspection). To many Latvians, the collapse spoke to larger issues such as political corruption, corporate abuse (the large supermarket chain was accused of providing poor safety training, several work safety violations and poor treatment of employees paid below minimum wage) and government failures. Dombrovskis was replaced by Laimdota Straujuma, a well-regarded agriculture minister and former economist who became the first woman to be Prime Minister. She formed a government with Unity, the Reform Party (as it is now known), the NA, independents and also the ZZS (excluded from Dombrovskis’ ‘anti-oligarchs’ government in 2011).

Latvia is preparing for a general election in October 2014, so the EP elections were of less importance although still an early test for the general elections in the fall. Turnout fell to only 30%, the lowest in the three EP elections held since 2004 (in 2009, turnout was a high 53.7% due to same-day local elections, but still stood at a ‘healthy’ 41.2%), and all parties except Unity lost votes from the 2011 election. Unity won an unexpectedly massive victory, scoring 46.2% of the votes and – as touched on – won more votes (204.9k) than in 2011 (172.5k). It is likely a vote of confidence for a fairly popular government, which has presided over a strong economic recovery (Unity ran on the need to stay the course with fiscal discipline) and has been generally less corrupt than past governments. Another factor which helped the governing party was the candidacy of former Prime Minister Valdis Dombrovskis, who personally received 148,056 plus votes and only 6,214 strike-throughs.

The National Alliance placed a surprise second, with a strong result of 14.3%. The party was founded in 2010-1 by the merger of two right-wing nationalist parties – the conservative right-wing For Fatherland and Freedom/LNNK (TB/LNNK) and the smaller far-right All for Latvia! (VL). It is a Latvian nationalist party, known for its anti-Russian positions and advocacy of tougher citizenship and language laws. The NA sits with the British Tories in the ECR group, an association which has caused headaches for the Tories since the NA’s members have participated in celebrations and commemorations for the Latvian Legion, a Waffen-SS formation of Latvian conscripts who fought the USSR during World War II. The NA’s two components have been branded as fascist or Holocaust deniers by the party’s opponents, although some of these claims are somewhat flimsy. Although the NA is somewhat Eurosceptic and anti-federalist, the Euroscepticism does not compare to the anti-EU views of far-right parties in older member-states and Latvian nationalists traditionally tend to be somewhat pro-NATO and pro-EU to oppose Russia. The party’s relative success in 2014 has been attributed to prevailing anxiety in the Baltics over events in Ukraine/Crimea, and the NA campaigned in favour of stronger pan-EU energy and foreign policies and strengthening the EU’s sanctions against Russia.

The main loser was the SC, which ran divided in this election. The largest and most moderate component of the SC alliance, the Social Democratic Party “Harmony” (SDP’S’), associated with the S&D, won 13% and only one seat, a poor result. Incumbent MEP Aleksandrs Mirskis left the SC and formed his own party, Alternative, which won 3.7% of the vote. The smaller and more radical component of the SC, the Latvian Socialist Party (LSP), ran separately this year (like in 2004 but unlike in 2009). The LSP is led by outgoing MEP Alfrēds Rubiks, a former hardline Communist Party apparatchik who opposed independence and was arrested in 1995 for ‘subverting state power’ and supporting the August 1991 coup attempt in Russia. Banned from running for or holding national office, Rubiks has been an MEP since 2009. The LSP won only 1.5% of the vote running independently, similar to its result in 2004. The Latvian Russian Union (LKS) – formerly For Human Rights in United Latvia (PCTVL) – held its sole MEPs, although its support declined further to 6.4%. The LKS/PCTVL was the most popular Russian party for a while in the 1990s, but it has gradually been decimated by the SC since 2006, and lost its last seats in the Saeima in 2010. The LKS was likely kept alive in the EP elections by its incumbent MEP, Tatjana Ždanoka, another former Communist Party apparatchik who has found herself banned from office in Latvia (former ‘active members’ of the Communist Party are still banned from public office nationally). The LKS sits with the European Free Alliance (EFA) in the G-EFA group, although there has been some recent unease between the two due to the G-EFA’s positions on the Crimean crisis.

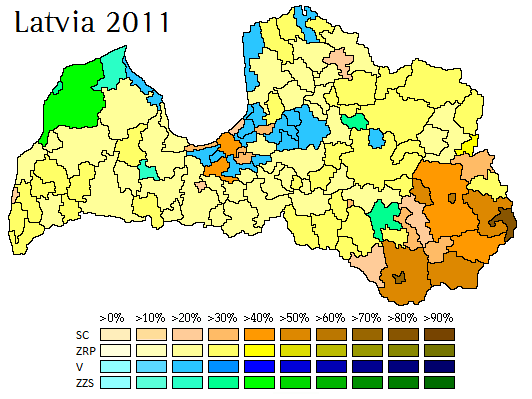

Besides the division of the vote, the Russian parties were hurt by lower turnout from Russian voters. In Latgale region, for example, turnout was 23.4% (the lowest in the country). The SDP’S’ won only 23% against 38.7% in Riga, while in Latgale it faced strong competition from Aleksandrs Mirskis’ Alternative: the former won 20.9% and the latter won 20.3%. Alternative was the largest party in Daugavpils city and municipality, while the SDP’S’ was strongest in Zilupes, a municipality on the Russian border which is 54.9% Russian and 13.8% Belarusian, and in the city of Rēzekne, evenly split between Latvians and Russians. Alternative was weak in Riga (a bit over 2%) and totally absent from the Latvian countryside. Rubiks and the LSP retain a base in the old Ludzas District, with up to 16.6% in Ludza Municipality, a lone holdout of unreconstructed communists in Latgale. Overall, the Russian parties polled less than 5% together in most of the ethnically Latvian rural areas.

The Union of Greens and Farmers (ZZS), an alliance of the local Green Party and agrarian Latvian Farmers’ Union (LZU), which is more of an oligarchs’ party than anything (although it is generally eurosceptic and populist), won its first MEP, with 8.3% – a fairly disappointing result compared to 2011 and pre-election expectations. The party’s new MEP, who is from the LZU (the largest component, with 9 out of 13 MPs), will sit with the EFD group – the Greens, although to the right of other greens in the EU, are affiliated with the European Greens; many expected the LZU to sit with the ALDE, like Nordic agrarians in Scandinavia. A reason for the ZZS’ poor result – besides that it has tended to do much better in national elections – may be the ZZS’ poor result in and around oligarch Aivars Lembergs’ stronghold in Ventspils, where the ZZS won only 17% (in the city) and 25.9% (in the rural municipality) compared to 37.4% and 45.7% for Unity. The decrease in turnout and the NA’s gains were stronger around Ventspils. The ZZS is a predominantly rural-based party in ethnic Latvian regions, while the NA is stronger in urban and suburban Latvian regions.

Below the threshold, one of the most noted failures was that of ‘Latvian Development’, a centre-right neoliberal party founded by former New Era leader Einars Repše, a former Prime Minister (2002-2004) and later finance minister (2009-2010) behind the tough austerity measures during the crisis. The party spent an astronomical amount of money for one vote – about €54/vote (for all of 2.1%), beating previous records set by Šlesers in 2010 and 2011. Another new small party, the Latvian Association of Regions – a coalition of several local independents – won 2.5%, polling well in some of the strongholds of its local bosses, notably 20.7% in Preiļu Municipality in Latgale. The Reform Party, which seems to be in very bad shape, did not run.

Lithuania

Turnout: 47.35% (+26.37%)

MEPs: 11 (-1)

Electoral system: Semi-open list PR (preferential votes for up to 5 candidates), 5% threshold (national constituency)

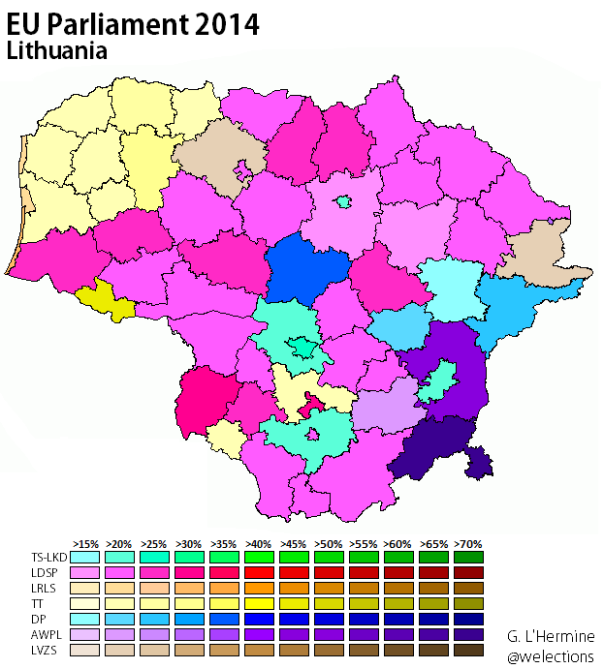

TS-LKD (EPP) 17.43% (-8.73%) winning 2 seat (-2)

LSDP (S&D) 17.26% (-0.86%) winning 2 seats (-1)

LRLS (ALDE) 16.55% (+9.38%) winning 2 seats (+1)

TT (EFD) 14.25% (+2.35%) winning 2 seats (nc)

DP (ALDE) 12.81% (+4.25%) winning 1 seat (nc)

AWPL/LLRA-RA (ECR) 8.05% (-0.15%) winning 1 seat (nc)

LVŽS (G-EFA) 6.61% (+4.79%) winning 1 seat (+1)

Green Party (G-EFA) 3.56% (+3.56%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Nationalist Union 2% (+2%) winning 0 seats (nc)

LiCS 1.48% (-1.9%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Coinciding with the second round of presidential elections which interested many more voters (but still only a minority), the EP elections saw significantly higher turnout than in 2009, when, as a stand-alone vote, only 21% of voters had bothered to vote – the second lowest in the EU.

Like Latvia, Lithuanian politics since 1991 have been marked by rapid government turnover, anti-incumbency and a highly fragmented party system in which new parties regularly emerge to perform quite well (before, in some cases, crashing and burning in seconds). In the past few years, politics may have stabilized somewhat, with less extreme anti-incumbent swings in elections and a Prime Minister (from 2008 to 2012) who became the first head of government to serve a full term in office. Lithuania’s political culture, however, is rather distinct from that of Estonia and Latvia. Because Lithuania’s Communist Party, in 1989, had broken from the CPSU and endorsed Lithuanian independence, the left has been less stigmatized by its communist past than in the other countries and it has been a significant force in national politics. The current Lithuanian Social Democratic Party (LSDP) was formed in 2000 by the merger of the original social democratic party (founded in 1896) and the stronger post-communist party born from the local Communist Party. Algirdas Brazauskas, the last leader of the local Communists, served as President (1993-1998) and Prime Minister (2001-2006) of Lithuania. Secondly, minority politics and issues are less contentious in Lithuania, which saw the least demographic upheavals of the Baltic states during Soviet rule. The Russian minority only makes up 5.8% of the population (and, at its peak in 1989, only made up 9% of the population against about 80% of ethnic Lithuanians) and is politically insignificant. The Polish minority (6.6%), far less controversial, is actually larger and more politically active. As a result, Lithuania adopted a fairly liberal citizenship law which effectively granted citizenship to all permanent residents in 1989.

Like Latvia and Estonia, Lithuania’s economy grew rapidly in the first years of the 21st century (growth didn’t falk under 7% between 2003 and 2008) because of the housing bubble and easy credit from abroad. Housing prices did not grow as much as in its two fellow Baltic neighbors, although the housing price index still surged from 102 in 2006 to a peak of 159 in 2008-Q2. Lithuania’s housing bubble burst slightly later and recession only hit in the last quarter of 2008, allowing Lithuania to be the only Baltic state to still record a positive GDP growth in 2008 (+3%). In 2009, however, housing prices tumbled and growth crashed to -14.8%. Unemployment likewise soared from 13.7% to 20.8% from January 2009 to January 2010. The country’s deficit blew up to 9.4% of GDP in 2009 and the country’s low government debt level increased from 15.5% in 2008 to 40.5% in 2012. Overall, the recession was less severe than in Latvia – and the country never needed to ask for a bailout from the EU-IMF, but to prevent such a scenario, the conservative government of Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius (2008-2012) implemented austerity measures including major spending cuts, public sector job cuts, some tax hikes and cuts to pensions and public sector wages. The government’s austerity policies suceeded in reducing the deficit to 3.2% of GDP in 2012 (and it dropped below the EU’s 3% limit in 2013) and the economy escaped recession as early as 2010 and recorded 3.7% growth in 2013. However, high unemployment (15-14% at the time of the 2012 election), the country’s very low minimum wage – the third lowest in the EU in 2012 and Kubilius’ perceived lack of empathy meant that the ruling centre-right Homeland Union-Lithuanian Christian Democrats (TS-LKD) paid the price for austerity in the 2012 election.

The TS-LKD won 15.1% of the vote and 33 seats in the 2012 election, a loss of 12 seats. The centre-left LSDP won 18.4% and 38 seats, becoming the largest party in the Seimas. The Labour Party (DP), an undefinable populist party led by shady Russian-born businessman Viktor Uspaskich (a ‘self-made man’ who made his money in pickles and gas), recorded significant gains from the 2008 election, placing first in the PR list vote with 19.8% and ending up with 29 seats in the Seimas. Uspaskich’s DP, founded just a year before, won the 2004 EP and legislative elections, and the DP formed a coalition with the LSDP and a social liberal party. Uspaskich resigned as finance minister in 2006 and fled to Russia, after being accused of false accounting for failing to declare over €4 million in income and expenditures. Upon his return to Lithuania in 2007, he was arrested and later released on bail. Uspaskich was shielded from prosecution by his parliamentary immunity as a MEP after 2009 and as a member of the Seimas since 2012. After the 2012 elections, the DP was was the focus of 10 judicial investigations into vote buying. Algirdas Butkevičius’ LSDP was set to form a coalition with the DP and another populist party, the vaguely right-wing Order and Justice (TT) party of impeached President Rolandas Paksas (2003-2004), who had been impeached for illegally granting Lithuanian citizenship to Russian businessman (and a contributor to his unlikely bid for President in 2003) Yuri Borisov, leaking confidential information to the same man and using his power to favour friends in a privatization deal. Paksas and Uspaskich have both denied the accusations against them, claiming that they are victims of political persecution. Both the DP and TT are anti-establishment populist parties, with only vague ideologies – the former, who sits in the ALDE group, has a distinctively left-wing name and left-wing populist positions; the latter, who sits in the EFD group (but is that group’s least loyal member), has a soft-Eurosceptic and law-and-order profile, but Paksas was previously a member of the LSDP, the TS-LKD and a liberal party. At times, the promises made by these populist parties are completely unrealistic – in 2012, Uspaskich promised to totally eliminate unemployment (0%) and resign if he didn’t.

Following the 2012 election, President Dalia Grybauskaitė, a very popular former European Commissioner who was elected to the presidency in a first round landslide in 2009, announced that she would reject any coalition with the DP, arguing that a party suspected of electoral fraud with a leader under investigation for false accounting and money laundering had no place in government. Nevertheless, Grybauskaitė appointed Butkevičius to form a government, in which the DP was included. Algirdas Butkevičius, a bland and uncharismatic politician, formed a coalition government with the participation of his party, the DP, the TT and the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania (AWPL/LLRA), the conservative party representing the Polish minority. Although she was unable to keep the DP out of government, Grybauskaitė intervened to keep high-profile portfolios out of the DP’s hands (they hold culture, agriculture, labour and education) while Uspaskich and his three key lieutenants are not in cabinet.

The government has appeared fairly unremarkable and uncontroversial so far. Vilnius aims to be the last Baltic state to join the Eurozone, in January 2015, and the government announced in early 2013 plans to raise taxes on high earners and property and move towards a progressive income and corporate tax to replace the existing 15% flat tax. The minimum wage was increased to 1,000 litas (€289.62/hour) and should be increased to 1,509 litas (€437.03). The DP has demanded an immediate increase in the minimum wage as a precondition for joining the euro, while the LSDP has warned that a rapid increase in one year would prevent the country for meeting the criteria for membership.

In July 2013, Viktor Uspaskich and his three associates were found guilty of false accounting (the DP avoided paying taxes and fees between 2004 and 2006 and hid up to €7 million in revenues) and he was sentenced to four year in jail. He briefly fled to Russia before returning home later in the month, and he has not served his jail sentence because of his parliamentary immunity. Furthermore, in these times of high tensions with Russia, Uspaskich’s murky business connections with Russian gas giant Gazprom and his suspected Russian sympathies have made him even more controversial. President Dalia Grybauskaitė, who has taken a very firm anti-Russian stance in the last few months – publicly saying that there is a real danger of war in Europe and that a new Cold War has begun, has excluded the DP from cabinet meetings where sensitive defense matters are discussed, suspecting that the DP is under Moscow’s influence.

In the first round of the presidential elections on May 11, President Dalia Grybauskaitė, running as an independent but supported by the opposition conservative TS-LKD and the Liberal Movement (LRLS), came out far ahead of the pack with 45.9% of the vote against only 13.6% for her closest rival, LSDP candidate Zigmantas Balčytis, who also led the LSDP’s list in the EP elections. The DP candidate, Artūras Paulauskas, a former Interim President and cabinet minister, won 12%. Former TS-LKD member Naglis Puteikis won 9.3%, the AWPL’s leader and MEP Valdemar Tomaševski won 8.2%, the mayor of Vilnius Artūras Zuokas won 5.2% and agrarian candidate Bronis Ropė won 4.1%. Although Grybauskaitė’s popularity has declined since her landslide victory in 2009, she remains highly popular, as a respected and competent strong-willed president. Recently, Grybauskaitė’s tough stances against the Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea and the events in Ukraine have boosted her popularity, in a country where there is very high anxiety and apprehension about Russia. In contrast, her Social Democratic opponent, Zigmantas Balčytis, urged diplomacy and conciliation with Russia while criticizing Grybauskaitė’s assertive style. The Lithuanian President has lost most of his/her power since independence, and is largely confined to a ceremonial and symbolic role while retaining some influence over foreign policy.

The second round of the presidential elections saw lower turnout than in the first round – 47.3% instead of 52.2% – but the relatively decent level of popular interest in the presidential election significantly boosted turnout in the EP election as a consequence. Lithuania has generally seen very low turnout, even in high-stakes national elections, so low-stakes elections held alone – like the EP elections in 2009 – can be expected to see very low turnout.

The opposition TS-LKD unexpectedly topped the polls, although with a paltry result of 17.4% which is down significantly on its result in 2009 (although because of turnout differences, it won far more votes than in 2009). Since its 2012 defeat, the TS-LKD went through a closely-fought internal leadership battle between former Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius, who eventually retained his job, and the party’s founder Vytautas Landsbergis. The right’s victory is likely due to differential turnout, with higher turnout recorded in the cities of Vilnius and Kaunas – where the conservatives traditionally do best/better. As in 2009, turnout was also significantly higher in Polish areas, with 57% turnout in Šalčininkai District Municipality, which is over 80% Polish. The higher turnout from Polish voters explains the AWPL’s strong performance, as in 2009: the Polish minority party received 8% of the vote, higher than the size of the Polish minority in Lithuania and higher than the AWPL’s 2012 result (5.8%, the party’s best result in a national legislative election). Some have also speculated that the TS-LKD and the Liberals (who won a very strong 16.6%) may have benefited from President Grybauskaitė’s unofficial support and potential coattails from her runoff victory, with 57.9% against 40.1% for the LSDP’s Zigmantas Balčytis.

The governing LSDP and DP both fell back from their 2012 results, with the DP falling from 19.8% in 2012 to 12.8% in 2014 – although its EP result this year is an improvement on its 2009 result, which had come on the heels of the DP’s poor showing in the 2008 legislative election. Order and Justice, with 14.3%, significantly improved on its 2009 and 2012 (7.3%) result; as did the LVŽS, the Peasant and Greens Union, whose result is up on 2009 and 2012 (3.9%). As in 2009, the DP and TT were led by their respective leaders, Viktor Uspaskich and Rolandas Paksas, both of whom were elected to the EP.

The electoral commission has some nice maps of the results of the EP results here and here (you can clarify some of the problems caused by the horrible shades on my map!). I’ve noticed a fairly strong regional dimension in Lithuanian elections, with parties having fairly well-defined regional bases of support. The TS-LKD tend to perform better in the cities of Kaunas and Vilnius; the Liberals do well in urban centres, but especially in the coastal city of Klaipeda (24.9% of the vote) and the resort town of Neringa (32.8%). The LSDP is weaker in Kaunas and Vilnius (only 12.1% in the latter), and stronger in more rural areas. The DP’s support, especially in 2014, was quite concentrated: the party won 38.9% in Kėdainiai District Municipality, which is the centre of Viktor Uspaskich’s business empire (his food processing, canning and pickles company ‘Vikonda’ is based in Kėdainiai and operates several plants in the region). TT is strongest in western Lithuania, with 32.8% of the vote in Paksas’ birthplace of Telšiai but also (for some reason unknown to me) 45.2% in Pagėgių municipality and 30.3% in the heavily Russian town of Visaginas (a town built for the largely Russian employees of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant, decommissioned in 2009). The AWPL, unsurprisingly, has very regionally-concentrated support as a minority party: it won 74.8% in Šalčininkai District Municipality (over 80% Polish), 54.6% in Vilnius District Municipality (53% Polish), 32.9% in the Russian town of Visaginas (the AWPL ran in coalition with the small Russian Alliance, a tiny party for the Russian minority), 22.4% in Trakai District Municipality, 17.7% in Švenčionys District Municipality and 15.9% in Vilnius city (which has a small Polish minority).

Luxembourg

Turnout: 95.92% (+5.16%)

MEPs: 6 (nc)

Electoral system: Preferential list PR with panachage (votes for a single party list of 6 candidates, or up to 2 votes per candidate or 6 different candidates from any lists), no threshold (national constituency) / mandatory voting enforced

CSV (EPP) 37.65% (+6.29%) winning 3 seats (nc)

The Greens (G-EFA) 15.01% (-1.82%) winning 1 seat (nc)

DP (ALDE) 14.77% (-3.89%) winning 1 seat (nc)

LSAP (S&D) 11.75% (-7.73%) winning 1 seat (nc)

ADR (ECR) 7.53% (+0.14%) winning 0 seats (nc)

The Left (GUE/NGL) 5.76% (+2.39%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Pirates 4.23% (+4.23%) winning 0 seats (nc)

PID 1.82% (+1.82%) winning 0 seats (nc)

KPL 1.49% (-0.05%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Luxembourg is the second smallest of the EU’s member-states both in terms of land area and population, but it manages to punch far above its weight in EU politics. Luxembourg, which occupies a strategic position in Western Europe between France, Germany and Belgium, has a long history of close ties to its neighbors (notably with Germany until 1918) and became a leading force in European diplomacy after World War II. The country was a founding member of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which placed Luxembourg’s large steel resources under supranational control, and Luxembourg City hosted the seat of the ECSC’s High Authority. The country’s leaders have been keen promote their country’s interests and ensure their representation in supranational institutions, to prevent larger domineering powers from overwhelming smaller member-states. Since then, Luxembourg has gained a reputation as an honest broker of compromises and trustworthy intermediary in European diplomacy. The country is the main seat of the Court of Justice, the Court of Auditors, the secretariat of the EP and a secondary meeting spot for the Council of Ministers. Luxembourgian politicians play a major role in EU politics: two former Prime Ministers, Gaston Thorn and Jacques Santer, have served as Presidents of the European Commission and now former Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker is set to become the next President of the European Commission. Juncker had previously been noted in his role as president of the Eurogroup. Luxembourg is said to be the most pro-European country in the EU. The country is also highly diverse and multilingual: Luxembourg has three official languages used interchangeably by a largely multilingual population, a majority of Luxembourgians speak English and 45% of the country’s residents are foreign citizens.

In stark contrast with the three previous countries I’ve looked at (Italy, Latvia, Lithuania), Luxembourgian politics have been tremendously stable for the past hundred years or so. It’s hardly surprising – it’s a small rich country where relatively little happens (outside of the two world wars). The Christian Social People’s Party (CSV), a Christian democratic centre-right party, has been Luxembourg’s traditional party of government – it has (or its pre-1944 predecessor) held the Prime Minister’s office since 1919 with the exception of 1925-1926, 1974-1979 and since 2013. However, all but one governments since 1919 have been coalition governments, traditionally led by the CSV in alliance with the two other major (albeit traditionally weaker) parties – the social democratic Socialist Workers’ Party (LSAP) or the liberal Democratic Party (DP). The CSV, LSAP and DP do differ on certain issues – the CSV remains influenced by a Catholic tradition while the DP and LSAP are secular (today, these differences are played out in attitudes towards religious education), the DP is usually the most liberal on economic issues favouring less government intervention (but is more interventionist than other European liberal parties and is hardly neoliberal) and the LSAP supports a strong welfare state and more government intervention (most recently its passionate defense of the indexation of wages to the cost of living/inflation) – but having often governed with one another, all three parties are moderate, pragmatic, strongly pro-European and fit in the broad centre of the political spectrum. The CSV, for example, has favoured Eurobonds (unlike Merkel) and preached solidarity by wealthier member-states. The CSV’s strongly federalist and even its more positions in favour of a more social and solidary Europe are somewhat at odds with the modern EPP mainstream. At the same time, Juncker has been criticized by the European left for staunchly defending Luxembourg’s status as something of a tax haven (after deindustrialization, Luxembourg reinvented itself as a major financial and corporate centre).

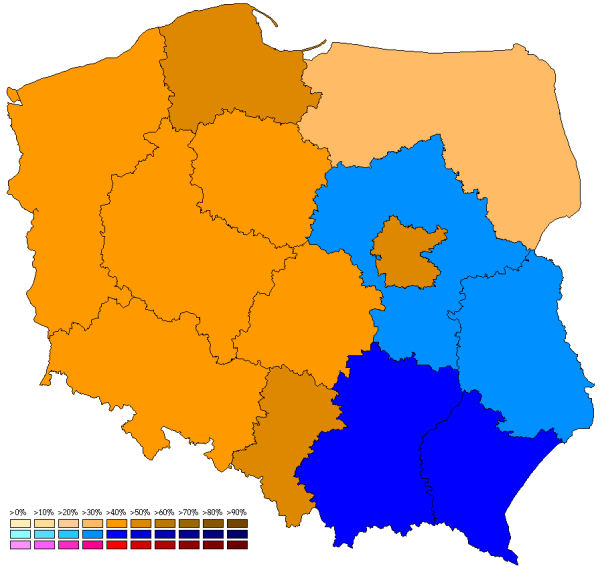

Leading party by commune – all won by the CSV (source: elections.public.lu)

Parties outside the three old parties have been more ideologically defined. The Greens, one of the strongest green parties in the EU, remain rather centrist and very pro-European (although they joined the smaller parties in opposing TAFTA). However, the right-wing Alternative Democratic Reform Party (ADR), a former pensioners’ party, has more right-wing stances – it is the most Eurosceptic of all parties (having opposed the 2005 Constitution and Lisbon), opposes voting rights for foreigners in national elections and has a populist focus on direct democracy and less bureaucracy. The ADR has fairly stable support at 8-11% in general elections (although it fell to only 6.6% in 2013), but that’s never been enough to elect an MEP. The Communist Party (KPL) survives as a more radical fringe party, being outpolled by the newer The Left, similar to Germany’s more well-known Die Linke (favouring redistribution, higher wages, more taxes on the wealthy) but less radical (it is not anti-EU).

Juncker was the EU’s longest-serving head of government until October 2013, having held the Prime Minister’s office continuously since 1995. He was forced to resign a year ahead of schedule, in July 2013, after a scandal in the state intelligence services (SREL). The SREL was accused of irregular and illegal activities including illegal wiretaps, bugging politicians, extrajudicial operations and maintaining files on citizens and politicians while Juncker, as minister responsible for the SREL, was accused by his junior partner (the LSAP) of failing to notice and report on illegal activities and deficiencies. For the first time in decades, voters went to the polls early in October 2013, meaning that these EP elections were the first which did not coincide with a general election. The CSV remained, as always, the largest party but lost 4.4% and 3 seats, while the liberal DP gained 3.3% and 4 seats – winning as many seats (13) as the LSAP, which won an all-time low result of only 20.3%. Xavier Bettel, the young openly gay mayor of Luxembourg City and DP leader, formed a coalition government with the LSAP and The Greens.

After last year’s ‘defeat’, the CSV roared back with a major victory in the EP elections while the governing DP and especially LSAP suffered substantial loses. Because the small country elects only six MEPs, these changes were still not large enough to produce changes in the distribution of seats. The CSV won 37.7%, a result up 6.3% on the CSV’s rather poor result in the 2009 EP election (down significantly from 2004, when Juncker also topped the CSV’s list in the EP elections) and up from 33.7% in last year’s national election. I wonder if the CSV may have benefited from a ‘Juncker effect’ which boosted its result, although because he wasn’t a candidate to the EP himself (unlike Schulz and Verhofstadt), that might be grasping at straws a bit. The CSV did have a popular candidate – Viviane Reding, a three-time European Commissioner (from 1999 to 2014), most recently at the justice portfolio, and a leading European federalist. She won the most votes of any candidate in Luxembourg – 126,888. Two incumbent CSV MEPs placed in fourth and fifth place nationally.

The DP won 14.8%, a result from 18.7% in 2009 and 18.3% in 2013. Incumbent MEP and former cabinet minister Charles Goerens was the second most popular candidate, winning 82,975 votes. The biggest loser of the election, however, was the LSAP – the party collapsed to a disastrous fourth place, winning only 11.8%, down from 20.3% in 2013 and 19.5% in 2009. The LSAP has been on a clear downwards trends for a number of years now, bleeding votes to the radical left, the Greens and other parties and suffering from poor and uninspiring leadership. The LSAP’s inability to claim the Prime Minister’s office in 2013 reflected poorly on Étienne Schneider, the LSAP’s leader and current Deputy PM. The LSAP also suffered from the lack of a popular candidate: its sole MEP, former education minister (and a fairly unpopular one at that) Mady Delvaux-Stehres, placed only ninth of all candidates nationally with 33,323 votes – all six of the CSV’s candidates polled more votes individually, as did the top candidates for the DP and The Greens.

The Greens, always stronger in EP than national elections, won an excellent 15%, although that’s down from an even stronger result of 16.8% in 2009. For comparison’s sake, the Greens won 10.1% in 2013.

All other parties failed to pass the threshold: for once, the ADR did better in the EP election than last year’s national election (6.6%); The Left improved from 3.4% in 2009 and 4.9% in 2013 and the Pirates, who won 2.9%, won a solid 4.2%. The Party for Integral Democracy (PID) is a party founded in 2012 by former ADR deputy Jean Colombera, a physician who practices homeopathic medicine, supports same-sex marriage and is under investigation for prescribing medical marijuana. In 2013, it won 1.5%, and increased its support to 1.8% with 9,314 votes for Colombera himself.

The CSV topped the poll in all 106 communes, even in traditionally Socialist regions in the Red Lands (southern Luxembourg), the heart of the country’s old iron ore and steel industry. In Luxembourg City, the CSV won 37.2% (+6.9%) against 17.5% for the DP (-4.64%), 16.3% for the Greens (-3.41%) and only 11.5% for the LSAP (-4.3%).

Malta

Turnout: 74.80% (-3.99%)

MEPs: 6 (nc)

Electoral system: STV, quota threshold (quota = votes cast ÷ seats + 1, national constituency)

Labour (S&D) 53.39% (-1.38%) winning 3 seats (-1)

Nationalist (EPP) 40.02% (-0.47%) winning 3 seats (+1)

AD (G-EFA) 2.95% (+0.61%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Imperium Europa 2.68% (+1.21%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Tal-Ajkla 0.48% (+0.48%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Alleanza Bidla 0.4% (+0.4%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Alleanza Liberali 0.08% (+0.08%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Malta is the EU’s smallest member-state both in terms of land area and population. Having joined the EU only in 2004, Malta has a very minor role and place in the EU (unlike Luxembourg) and its politics very rarely receive outside attention (something of a pity). Compared to other EU member-states – which largely have multi-party systems or at least some strong ‘third parties’ – Malta has a very solid and rigid two-party system (despite STV) marked by high voter loyalty to their parties, very limited spillover of preferences between the two parties, very high turnout (and it does not even have compulsory voting!), closely fought elections (losing parties rarely win less than 47% in general elections) and relative pro-incumbency. The two dominant parties are the Labour Party (MLP/PL) and the Nationalist Party (PN), two parties whose ideologies and identities have evolved significantly since their origins in the 1920s, when Malta was a British colony.

The PN was founded by Malta’s local pro-Italian elites, backed by the powerful Catholic Church, opposed to Anglicization measures; the MLP was originally a pro-British and anti-clerical party which supported Malta’s integration into the United Kingdom but later became pro-independence after integration failed in 1956. Dom Mintoff, Prime Minister of Malta between 1971 and 1984 and MLP leader since 1949, came to be the iconic figure of Maltese politics in the post-war years. A strong-willed, fiery and pugnacious leader, Mintoff defended his island’s independence and neutrality tooth-and-nail; his rule saw the negotiation of full independence as a republic, the scrapping of a defense agreement with the UK, the expulsion of the NATO commander, friendly ties with Gaddafi’s Libya and communist China, the growth of a modern and advanced welfare state, nationalization of key enterprises and major social reforms (gender equality, civil marriage and the decriminalization of homosexuality and adultery). Mintoff was not afraid to pick fights with his opponents, notably the Church, who interdicted the MLP between 1961 and 1964 (and Mintoff, in his last terms, tried to wrestle control of education and healthcare away from the Church) and his opponents claimed that he was an autocrat who bullied opponents, distributed patronage, gerrymandered districts and whose supporters even physically roughed up opponents. Mintoff remained in Parliament until 1998, and successfully plotted to have the Labour government of Prime Minister Alfred Sant (1996-1998) toppled from power in 1998. He died in 2012.

The PN has usually been pro-European and pro-Western since World War II, moderating its early pro-Italian and pro-fascist nationalism early on (in 1964, the PN negotiated independence for Malta – as a member of the Commonwealth retaining the Queen as head of state and a British Governor General, and signed a military agreement with NATO) and leading the charge for EU accession in the 1990s, with Labour opposed. In the 2003 accession referendum, Labour and Mintoff opposed EU membership and only 54% voted in favour in the end, although the MLP has since made its peace with the EU.

The PN governed Malta for all but two years (1996-1998) between 1987 and 2013, pursuing a fairly generic pro-European, pro-Western conservative centre-right policy. With the MLP abandoning its Euroscepticism and non-aligned foreign policy (although the new Labour government has been building better economic/business relations with the PR China) and the PN moderating its Catholic social conservative stances (although Malta remains extremely socially conservative by European standards: divorce was only legalized in 2011 and Malta is the only EU country where abortion remains technically illegal in all circumstances; but the new Labour government legalized same-sex civil unions and adoptions in April 2014 with PN abstentions), the differences between the MLP and PN have been blurred – but, unlike in other EU countries, this hasn’t led to major disalignment from the major parties or weakening in partisan identities. In the 2013 election, Nationalist Prime Minister Lawrence Gonzi and Labour leader Joseph Muscat had fairly similar policy platforms. The MLP won the March 2013 elections by a ‘landslide margin’ by Maltese standards – 54.8% and 39 seats against 43.3% and 30 seats for the PN (a 35,000 vote margin and the largest victory for one party since 1955). Because Malta’s economy is performing quite well, the PN was the victim of voter fatigue, perceptions of Nationalist complacency and aloofness, corruption scandals, unpopular policy decisions and high utility prices. Joseph Muscat, who at the young age of 40 represents a new generation of pro-European and moderate ‘European’ social democrats in the MLP, became Prime Minister.

Muscat’s government does not seem to have done anything particularly unpopular or spectacular since taking office over a year ago, with the government claiming that it has created more jobs than the PN governments and was saving families money by cutting utility rates. In the summer of 2013, Muscat was embroiled in a row with the EU over his government’s controversial plan to turn back asylum seekers – because of its location, Malta is on the ‘frontline’ of waves of immigration from North Africa, who often seek to reach the EU in makeshift boats (who often capsize, with terrible loss of life). In November 2013, the PN attacked a government project to sell Maltese (=EU) citizenship to qualified applicants for €650,000 – targeting ‘high quality’ foreigners and investors. The EP elections were something of a test for the government and opposition: the last two elections to the EP in Malta were won by the then-opposition (MLP) by unusually large margins (a 4-2 seat split in the MLP’s favour in 2009), so the PN was optimistic about its chances and the party’s new leader, Simon Busuttil, set the objective of a 3-3 split in seats.

The ruling Labour Party won the elections, with a slightly reduced majority compared to the 2009 EP elections, while the opposition PN did poorly with a result similar to its very poor 2009 result (and below its 2013 result). However, the PN can mask its disappointing result in the popular vote by pointing out that it succeeded in its objective of gaining a seat from the MLP to get a 3-3 split in seats.

The last two MEPs – from the MLP and PN – were elected on the 28th count without a quota, with PN candidate Therese Comodini Cachia winning with 206 more votes than the unsuccessful MLP candidate. The University of Malta has Excel files with full count details and party transfers. I’m not sure what explains the PN’s success at gaining a third seat in the STV count: it might be the PN having one less candidate, intricacies in the efficiency of vote transfers from PN candidates (although both MLP and PN votes transferred to their colleagues at 94% efficiency; but one PN MEP elect had his votes transfer to the eventual final PN MEP-elect on the 26th count with 99.7% efficiency vs. 93.2% for the transfer of votes for a defeated MLP incumbent in the final 28th count) and a minor edge to the PN in transfers from the green AD (although 46.7% of the AD’s votes were non-transferable, 31.2% went to the PN against 22.2% for the MLP in the 21st count).

The election saw the political return of former MLP Prime Minister Alfred Sant, whose short-lived government froze EU accession talks in the 1990s and went on to lead Labour to defeat at the hands of the PN in the 1998, 2003 and 2008 elections (as well as in the 2003 EU referendum). He is somewhat controversial with parts of the Labour base, but retains significant support. In the end, he was elected on the first count with 48,739 first preference votes (19.4%), over 12.7 thousand votes over the quota.

Minor parties improved on their 2009 performances. The green centre-left AD, led by Arnold Cassola (an academic and former Italian Green MP for Italian expats in Europe from 2006 to 2008), won nearly 3% – up 0.6% from 2009. But in 2004, the AD had done exceptionally well with 9.3% (a huge result for a third party in Malta) and Cassola was only eliminated on the final count. The far-right Imperium Europa (likely one of the EU’s most bizarre far-right parties: it supports European unity but from a white supremacist/racial standpoint and fascist/neo-Nazi orientation; in its words “A Europid bond forged through Spirituality closely followed by Race, nurtured through High Culture, protected by High Politics, enforced by the The Elite”) won 2.7%, with 6,205 first prefs for party leader Normal Lowell, up from 1.5% in 2009.

Turnout hit an all-time low of 74.8%, which is extremely low by Maltese standards (although most European countries can only dream of achieving such levels of turnout without compulsory voting) – which saw a ‘low’ turnout of 93% in 2013 (!). In 2004, turnout was 82.4% and dropped to 78.8% in 2009.

Netherlands

Turnout: 37.32% (+0.57%)

MEPs: 26 (nc)

Electoral system: Semi-open list PR (vote for a party or a single vote for one candidate on the list), no threshold (candidates may be elected out of list order if they win 0.96% or more of the vote; electoral alliances between parties allowed – votes cast are pooled and treated as a whole), national constituency

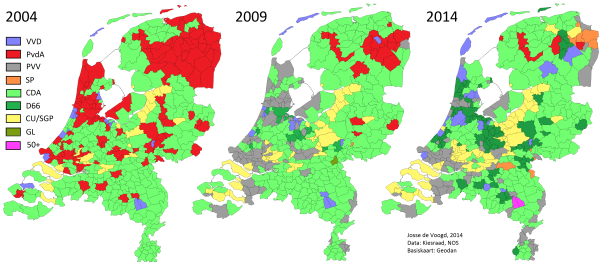

D66 (ALDE) 15.48% (+4.16%) winning 4 seats (+1)

CDA (EPP) 15.18% (-4.87%) winning 5 seats (nc)

PVV (EAF) 13.32% (-3.65%) winning 4 seats (-1)

VVD (ALDE) 12.02% (+0.63%) winning 3 seats (nc)

SP (GUE/NGL) 9.64% (+2.54%) winning 2 seats (nc)

PvdA (S&D) 9.4% (-2.65%) winning 3 seats (nc)

CU-SGP (ECR/EFD > ECR) 7.67% (+0.85%) winning 2 seats (nc)

GroenLinks (G-EFA) 6.98% (-1.89%) winning 2 seats (-1)

PvdD (GUE/NGL) 4.21% (+0.75%) winning 1 seat (+1)

50PLUS 3.69% (+3.69%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Pirates 0.85% (+0.85%) winning 0 seats (nc)

Others 1.58% (-0.4%) winning 0 seats (nc)

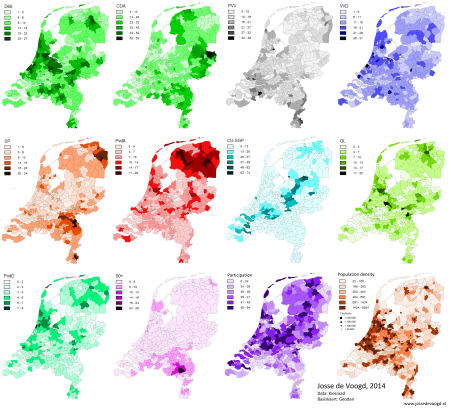

Map credit: Josse de Voogd

The Netherlands, since the mid-1960s, have gradually moved from having one of the most stable party systems in Europe to one of the most volatile, unpredictable and fragmented. Up until the 1960s, Dutch politics were divided by the strict and rigid system of pillarisation – voluntary religious, political and social segregation of society into four pillars, each with their own parties, trade union, newspaper, radio station, cultural activities/organizations, schools, hospitals and even sporting activities. These pillars were Protestant, Catholic, socialist and ‘general’ (liberal); the Protestants and Catholics’ parties united politically to rule the Netherlands for much of the twentieth century – at least one confessional party was in government between 1918 and 1994 (oftentimes all three major confessional parties were in), usually admitting the liberals or socialists to rule in coalition (for example the ‘Roman-Red’ coalitions spearheaded by the centre-left Labour Party and the Catholic party between 1946 and 1958; or the Christian democrats’ regular alliances with the liberals from 1959 to 1989), and held an absolute majority in Parliament between 1918 and 1967. The denominational pillars, especially the Catholic one, were the most organized and had the tightest grip on their masses; the liberal pillar, largely made up of irreligious or non-practicing Protestant educated middle-classes or elites, was the worst organized pillar. Voting shifts were relatively minor, and mostly happened between blocs – for example, the Communist Party (CPN) in the post-war years was gradually weakened while the Labour Party (PvdA) was strengthened. However, with the rise of a modern and increasingly deconfessionalized society in the mid-1960s, Dutch society was progressively ‘depillarised’ and the Protestant (ARP, CHU) and Catholic (KVP) lost many votes, while the right-liberals (People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, VVD), Labour and new parties on the left and centre benefited (most notably Democrats 66, or D66, a new anti-pillarisation and left-liberal party advocating for democratic reform, which was founded – you guessed it – in 1966).

Beginning in the 1970s, Dutch politics – facilitated by one of the world’s most proportional electoral systems – became increasingly volatile and unpredictable, with larger swings from election to election – D66 has a famously ‘floating’ and highly volatile electorate, as the second-choice of many liberals and leftists it has a very high ceiling but lacking a solid, loyal clientele it has a very low floor, so it has tended to collapse when it is in government but able to surge to high levels when it is in the opposition. Nevertheless, until 1994, the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) – formed in 1977 by the merger of the Catholic party (KVP) and the two major Protestant parties (Abraham Kuyper’s Anti-Revolutionaries, and the Christian Historical Union or CHU) – remained the largest party in Parliament and was in every cabinet. As a centrist, middle-of-the-road and consensual party (although one which more often than not leans to the right), it retained the old Catholic/Protestant bloc’s ability to structure consensus-driven Dutch politics around itself and governed in coalition with either the right-liberal VVD or the PvdA.

For a variety of reasons including unpopular policy decisions and its own arrogance, the CDA (and its then-junior ally, the PvdA) suffered major loses in the 1994 elections, in which D66 won a record 15.5% and 24 seats. D66, whose lifelong aim had been to realign Dutch politics by throwing the Christian democrats out of power, finally got their wish in the form of an historic ‘Purple coalition’ with the PvdA and the VVD, with the centrist D66 providing the glue to hold the centre-left and centre-right parties together. The Purple cabinets led by Wim Kok, in power from 1994 to 2002, were a typically ’90s type of government: mixing economic liberalism (tax cuts and strongly favourable to free markets) and social liberalism (multiculturalism, open immigration policies, early legalization same-sex marriage, legalization of euthanasia and prostitution). Initially popular, after two terms in power, the Purple arrangement had become deeply unpopular by 2002 – both the PvdA and VVD (without mentioning D66, which had predictably collapsed upon entering government) had lost support because the Purple coalition obscured both parties’ identities and created major dissatisfaction with their voters. The PvdA became closely wedded to economic liberalism and free-market policies, losing support on the left; the VVD, less cripplingly, was forced to be quiet about immigration.

In 2002, a charismatic populist leader, Pim Fortuyn – an openly gay former Marxist sociology professor, exploited the unpopularity of the Purple government (he published a hard-hitting best-seller about the ‘wreckage’ of the Purple government) and growing concerns about immigration (particularly Muslim). Fortuyn took anti-immigration and anti-Islam positions from an original, socially liberal, standpoint, arguing that Islam was a ‘backwards religion’ and an existential threat to Dutch liberal society (he supported same-sex marriage, euthanasia, women’s rights, drug legalization). Fortuyn’s charismatic, anti-establishment, combative (notably deliberately provoking an imam by giving him gaudy details of sexual activities he had performed, and picking the fruits when the imam blew up) and foul-mouthed style was a big success in 2002, and his newly-founded personalist party, the LPF, became a frontrunner in that year’s election. However, Fortuyn was shockingly assassinated by an animal rights’ activist only a week before the election. The LPF nevertheless did remarkably well, with 17% and 26 seats, placing second. The PvdA was decimated, losing 22 seats, while the VVD also lost 14 seats. Unnoticed at the time, the Socialist Party (SP), a radical left party which had begun as an obscure Maoist cell in the 1970s, gained 4 seats to win a total of 9 (it had first entered Parliament in 1994 and made gains in 1998). Ironically, the most lasting immediate result of the Purple government’s collapse was the CDA’s resurgence and re-installation in power for 8 years. Although it had performed very poorly in opposition since 1994, the CDA benefited from its time-honoured place in the centre and became a safe, moderate option for many voters seeking stability. The CDA’s leader, Jan-Peter Balkenende, a largely uninspiring and terribly bland leader, became Prime Minister in a short-lived coalition with the VVD and LPF.

However, the LPF, lacking its charismatic leader, quickly became a clown show and new elections in 2003 saw the LPF collapse to only 8 seats (and would proceed to disintegrate completely by 2006), while the traditional parties – CDA, VVD and especially Labour – regained some lost ground. Balkenende replaced LPF with D66, which had been further weakened in the elections (to 6 seats, after having been halved in 2002). Balkenende gained a reputation for being a teflon politician, given that few people ever thought much of him and he was a poor leader, surviving the premature of his cabinet in 2006 (D66 withdrew) and managing to form another cabinet (this time with the PvdA and a small Christian party) after the early elections in 2006.

The Purple government and Fortuyn’s success have both dramatically altered political dynamics in the Netherlands, making them even more fragmented and volatile.

Fortuyn’s anti-immigration and anti-Islam rhetoric has continued to be a central issue in Dutch political debate, reignited by particular events such as the 2004 assassination of controversial anti-Islam filmmaker Theo van Gogh. Politically, Fortuyn’s place was taken up by Geert Wilders, a former VVD MP who founded his own party, the Party for Freedom (PVV) in 2006 and won 9 seats in that year’s election. Wilders is a more traditional far-right leader, although like Fortuyn, Wilders is a charismatic and abrasive character whose party still revolves almost entirely around his personality, his mood swings and his favourite art of provocation. The PVV gained national (and international) attention by successfully (but temporarily) monopolizing debate on immigration issues and by taking up various wedge issues – banning dual citizenship, a burqa ban, a ban on the Quran, comparing Islam to totalitarian ideologies and generic attacks on Muslim immigrants (and, more recently, Eastern European workers). Like the LPF, the PVV may sometimes couch its rhetoric in social liberal language, although Wilders is a more typical right-wing populist than Fortuyn. Economically, Wilders started out on the right, supporting economic liberalism – similar to the early hard-right positioning of the FN in France in 1984 – but, like the FN, has shifted to idiosyncratic/syncretic economic stances often misleadingly said to be ‘centrist’ or ‘left-wing’. The PVV supports tax cuts, spending cuts in certain area (environmental program, foreign aid, development etc), simplifying business and ‘welfare chauvinist’ positions (limiting access to welfare benefits); but it also moved towards supporting many welfare measures or interventionist policies (child benefits, unemployment benefits unchanged, retirement age kept at 65). The PVV revolves entirely around Wilders, who is legally the party’s sole member – a unique party model, perhaps comparable only to Silvio Berlusconi’s very early Forza Italia in 1994. Wilders vets the PVV’s candidate himself, there is no party democracy and the PVV has not built a local base – in fact, even in the March 2014 local elections, the PVV competed in only two (The Hague and Almere) municipalities out of 403.

In the past decade, Dutch voters have built no strong links with any party, and switched back and forth between parties in between and during elections – although most of the swings have been within blocs, with battles on the left, right and now centre for dominance. In 2006, the SP, benefiting from the CDA government’s unpopular welfare reforms and the PvdA’s poor performance, won a record 16.6% and 25 seats but neither the SP nor the CDA had any interest in government cooperation and the SP’s support fell substantially. In 2009, Wilders’ PVV surged to 17% in the EP elections. Balkenende’s government once again collapsed prematurely in 2010, after the PvdA rejected an extension of the Dutch mission in Afghanistan agreed upon by the CDA’s Balkenende and heir-apparent, foreign minister Maxime Verhagen. By that point, Balkenende had reached his expiry date and, having failed to lead any one of his governments to their full terms, now appeared as a very weak and indecisive leader. Therefore, in the 2010 early elections, the CDA collapsed into fourth place – winning 13.6% and 21 seats, the worst result in the party’s history. Meanwhile, Wilders’ PVV surged to 15.5% and 24 seats. The other major winner was the right-liberal VVD, which had tacked right on immigration issues as well, and placed first – an historic feat for Dutch liberals – with 20.5% and 31 seats. The SP lost heavily (-10 seats), D66 began its recovery after four disastrous elections (+7 seats).

Following tortuous coalition negotiations, VVD leader Mark Rutte formed a minority government with the CDA, which received the outside support of the PVV. While the PVV quickly indicated that it felt no deep obligation towards the cabinet, Wilders basically agreed to support Rutte’s stringent austerity measures in exchange for much stricter immigration laws. The government therefore both severely tightened immigration laws and adopted austerity measures aimed at reducing the Netherlands’ deficit from 5.1% of GDP to the EU level of 3%. Wilders’ support continued to push towards the VVD, to the dismay of certain moderate liberals. For example, Rutte became a ‘hawk’ in EU bailout negotiations and in 2012 said that he would inflexibly oppose any new transfer of sovereignty to the EU. The VVD, always torn between liberals and conservatives or populist-liberals and progressive liberals, has now become one of the most right-wing and Eurocritical parties in the European liberal family (ALDE) and may perhaps be more easily comparable to David Cameron’s Tories.

With these policies, Rutte’s first government was certainly one of the most right-wing governments in Dutch history, and was extremely unpopular with the left – either for its deep budget cuts, its anti-immigration policy, its association with Wilders or all three. Economically, the opposition blamed the government’s austerity policies for throwing the Netherlands, which had escaped fairly well from the 2009 recession, into a double-dip recession with -1.2% negative growth in 2012.

Politically, the government caused problems for both the CDA and the PVV. For the CDA, their issues were quite straightforward: they continued to disingenuously claim they were centrists while supporting a very right-wing government devastated its remaining credibility and indirect cooperation with the PVV caused major strains in the CDA, particularly with the centre-left minority within the party which never wanted to go into government in the first place. For the PVV, the party’s profile began to fade after a few Wilder missteps (notably criticizing the Queen for wearing a veil while in Oman and launching a quite crass new vendetta against Eastern Europeans) and less interest on immigration/Islam (which were huge issues in 2010). In April 2012, Wilders pulled the plug on the government, unwilling to accept a new round of austerity policies and claiming that austerity would have a negative impact on social programs, notably old age security. Wilders unsuccessfully tried to adopt a new anti-EU, anti-euro and anti-austerity creed. The PVV now advocates total withdrawal from the EU and the Eurozone, and Wilders famously associated himself with Marine Le Pen’s FN.

The early 2012 elections are a textbook example of the Dutch’s electorate volatility. The campaign started out as a contest between Mark Rutte’s VVD and Emile Roemer’s SP, which had surged into a strong second or even first place in polls as the PvdA again struggled in opposition. Rutte’s policies were disliked, but Rutte was seen in a positive light as being a genuine and ‘refreshing’ leader. Roemer had become the most vocal opponent of the government’s austerity, and his party’s populist and Eurosceptic rhetoric was ostensibly popular with voters. The left-wing populist SP strongly opposes austerity policies at home or in the EU, and while the SP does not advocate for full withdrawal from the EU, the party is very critical of the ‘EU superstate’ for its advocacy of austerity, corporate interests and its undemocratic workings (it is notably the only Dutch left-wing party which is Eurosceptic). The SP therefore opposes transfers of sovereignty to Brussels, the Stability and Growth Pact, it has been critical of freedom of movement (notably for Romanians and Bulgarians, because of social dumping), the Euro (it does not support withdrawal, but at the same time it doesn’t want to save it at all costs), neoliberal trade policies and the EU common market. Much (too much, probably) is often made of the ‘overlap’ between the PVV and the SP since both parties are anti-EU populists.

The PvdA, which has been on the verge of losing dominance of the left several times in the past few years, managed to turn the 2012 election around in its favour. The PvdA’s new moderate leader, Diederik Samsom, made a good impression in the debates while the SP’s soft support came apart as its platform was criticized (an independent analysis of the SP’s platform said it would result in many job loses). Therefore, there was a sudden and rapid reversal of fortunes for the SP late in the 2012 election – which became a ‘prime ministerial election’ between Rutte and the PvdA’s Samsom. At the polls, the VVD and PvdA both did very well due to strategic voting on the left and right. The VVD won a record-high result of 26.6% and 41 seats, while the PvdA won 24.8% and 38 seats. The SP ended up with a very disappointing result of 9.7% and 15 seats, no change on 2010. Wilders’ PVV suffered a (temporary) setback, falling to 10.1% and 15 seats. The CDA suffered another major thumping, winning a record-low 8.5% and only 13 seats. D66, with 8% and 12 seats, further improved its standing. One of the other major losers was GroenLinks (or GreenLeft), the green party founded in 1989 by the merger of four parties including the New Left-type Pacifist Socialists (PSP), the Christian left/moderate green Political Party of Radicals (PPR) and a recently destalinized Communist Party (CPN) which had embraced the New Left. Since its creation, the GreenLeft has become a much more moderate party, especially under the leaderships of Femke Halsema (2002-2010) and Jolande Sap (2010-2012). The party sidelined the ‘fundi’-type radical left factions, moderated its pacifism with the Kosovo and Afghanistan issues, made a major bid to appear as a respectable and responsible potential governing party and shifted towards a kind of post-materialistic progressive green liberalism (more ‘modern’ than the PvdA) under Halsema and Sap. Although Halsema was fairly successful, and the party won 10 seats in 2010, what did the party in was its 2012 decision to help the outgoing VVD-CDA government to pass its budget before snap elections (after the PVV left the coalition). The GreenLeft joined a ‘Kunduz coalition’ (named for the coalition of parties which approved the 2011 extension of the Dutch policing mission in Kunduz, Afghanistan) with the two governing parties, D66 and the ChristianUnion (CU). Although the GreenLeft managed to get environmental policies and a withdrawal of budget cuts to arts and culture, the damage was done and added to existing internal strife.

The coalition negotiations proved unusually short by Dutch standards, with the formation of a VVD/PvdA coalition government by November 2012. It is a Purple-type government, lacking D66 as a ‘mediator’. Since 2012, the Dutch electorate has been tremendously volatile with one key underlying trend – both governing parties have become extremely unpopular and would be headed to a landslide defeat in the next election. The PvdA quickly lost the ‘additional’ strategic votes it had won from the left. The VVD’s support suddenly collapsed in November 2012 after the coalition agreement talked about increased health premiums for high-income earners – the VVD’s core electorate.

The Purple-ish Rutte II government has since continued with austerity policies (perhaps slightly less ‘extreme’ than those of his first right-wing cabinet) while the economy has continued to struggle. The economy shrank by 0.8% in 2013 but should grow by 1.2% in 2014; unemployment has grown from about 4% in 2011 to a projected high of 7.4% this year. The country’s deficit is now below the EU’s 3% limit (-2.5%), exports are doing well and the debt is not huge (73.8%); instead, what has been dragging the economy has been the very high levels of household debts (110% of GDP, encouraged by fully tax-deductible interest payments on mortgages) creating low consumer confidence and public consumption. Following a significant slump in house prices, 16% of households owed mortgages higher than the value of their house. European Commissioner Olli Rehn has cheered on the government’s spending cuts and austerity, even demanding that they cut even more, but many have said that the cuts serve to further undermine consumer confidence and worsening the economy.

The government has continued to take hardline stances in the Eurozone crisis. The PvdA finance minister, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, is the new president of the Eurogroup and was seen as responsible for the (disastrous) tough position against Cyprus in 2013. The current President of the European Council, Herman van Rompuy, has said that Rutte threatened to leave the Eurozone in 2012 if the EU pushed through a ‘reform package’.

The PvdA ‘talked left’ (left-ish, to be fair: Samsom, at the time, was compared to François Hollande – when that comparison wasn’t an insult! – and still does remind me of Hollande) in 2012 but has since definitely ‘walked right’; the party has always been quite moderate since 1994, pragmatically supporting economically liberal, free-market policies when it is in government. The party has a real threat to its left in the form of the SP, but it also has the imperative to be moderate if it is to be in governments (bad memories of 1977, when a very strong but quite left-wing PvdA under Prime Minister Joop den Uyl found itself removed from power by a CDA-VVD coalition because its demands were too much for the CDA) and also has rivals to its right (in the form of D66). How can the PvdA ‘hold the left’ while remaining centrist enough for government?

In polls, Wilders’ PVV, whose radical anti-EU platform seemed to be working, surged to new heights – up to 27-31 seats in polls, leading the field or tied with the VVD. On the left, the PvdA’s numbers have tanked, now being pegged below 20 seats in all but one poll in 2014, and being outpolled by the SP, which has polled up to 24-25 seats.