Category Archives: Greece

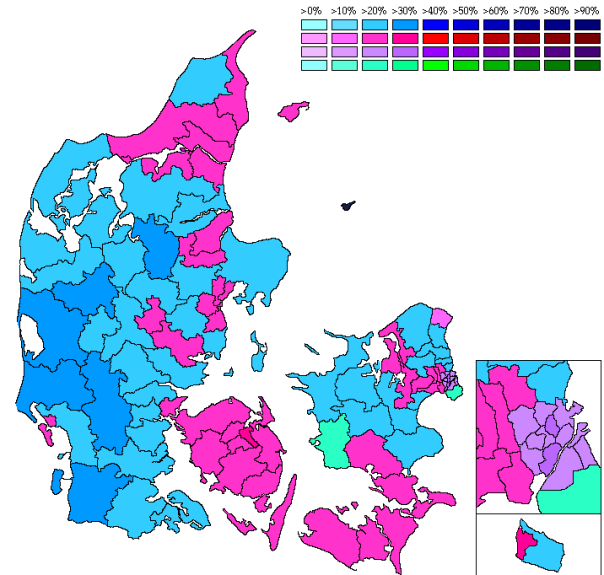

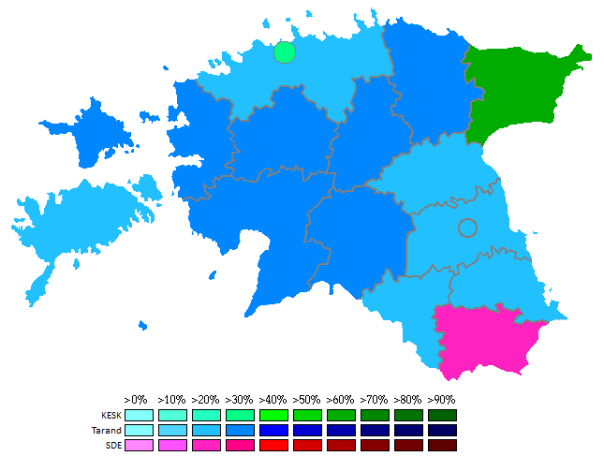

EU 2014: Germany to Hungary

After France, this post looks at the EP election results in some of the most important member-states in EU affairs today – Germany and Greece (as well as Hungary, important in its own way).

These posts do not include, generally, descriptions of each party’s ideology and nature. For more information on parties, please refer to older posts I may have written on these countries on this blog or some excellent pre-election guides by Chris Terry on DemSoc.

Note to readers: I am aware of the terrible backlog, but covering the EP elections in 28 countries in detail takes quite some time. I promise to cover, with significant delay, the results of recent/upcoming elections in Colombia (May 25-June 15), Ontario (June 12), Canadian federal by-elections (June 30), Indonesia (July 9), Slovenia (July 13) and additional elections which may have been missed. I still welcome any guest posts with open arms :)

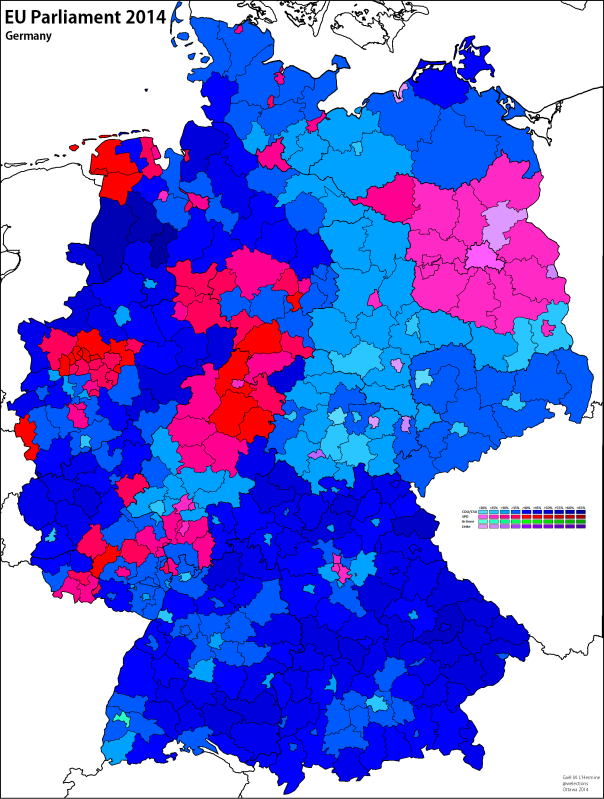

Germany

Turnout: 48.12% (+4.85%)

MEPs: 96 (-3)

Electoral system: Closed list PR, no threshold (effectively 0.58%)

CDU (EPP) 30.02% (-0.7%) winning 29 seats (-5)

SPD (S&D) 27.27% (+6.5%) winning 27 seats (+4)

Greens (G-EFA) 10.7% (-1.4%) winning 11 seats (-3)

Die Linke (GUE/NGL) 7.39% (-0.1%) winning 7 seats (-1)

AfD (ECR) 7.04% (+7.04%) winning 7 seats (+7)

CSU (EPP) 5.34% (-1.9%) winning 5 seats (-3)

FDP (ALDE) 3.36% (-7.6%) winning 3 seats (-9)

FW (ALDE) 1.46% (-0.2%) winning 1 seat (+1)

Pirates (G-EFA) 1.45% (+0.5%) winning 1 seat (+1)

Tierschutzpartei (GUE/NGL) 1.25% (+0.1%) winning 1 seat (+1)

NPD (NI) 1.03% (+1%) winning 1 seat (+1)

Family (ECR) 0.69% (-0.3%) winning 1 seat (+1)

ÖDP (G-EFA) 0.64% (+0.1%) winning 1 seat (+1)

Die PARTEI 0.63% (+0.6%) winning 1 seat (+1)

Others 1.76% winning 0 seats (nc)

Chancellor Angela Merkel’s ruling centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its Bavarian sister party, Horst Seehofer’s Christian Social Union (CSU), won the EP elections in Germany with 35.4% of the vote. Germany is widely seen as an ‘island of stability’ (and economic prosperity) in the midst of the EU, having managed to weather the economic doldrums which have hit most of the EU fairly well. With a population of nearly 82 million people, Germany is the most populous member-state of the EU and it has always been one of the key ‘engines’ of the EU, often in tandem with France. This has been particularly true in the last five or so years, for a variety of reasons. Politically, Germany’s leadership has been remarkable stable for nearly ten years – Angela Merkel, who took office as Chancellor in November 2005, is now the EU’s longest-serving head of government (after Estonia’s Andrus Ansip resigned early this year) and the country’s party system, despite minor but relevant shakeups since 2009, has not experienced the dramatic ups-and-downs, shifts or realignments seen in Greece, Italy, Spain, France, the Czech Republic, Ireland and even the UK. Economically, Germany has the EU’s largest economy – and also one of the healthier economies in the EU. Since 2010, Germany’s unemployment rate has declined from 8% to 5.3% (a feat which many of Germany’s neighbors and partners, notably France and Italy, can only dream about). Although economic growth has been unremarkable, Germany has a balanced budget and its public debt (77%) is declining. As the economic and political powerhouse of the EU and Eurozone, therefore, Germany has come to assume a leading role in the Eurozone crisis.

Merkel, with the Eurozone debt crisis, has gained an image as a tough and inflexible advocate of austerity policies, debt/deficit reduction in Europe’s most heavily indebted countries (Greece, Italy, Spain etc), enforcing strict fiscal rules in the EU (the European Fiscal Compact) and steadfast opposition to the idea of ‘Eurobonds’. Germany has been at the forefront, furthermore, of negotiations related to bailout packages for Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus. As a result, Merkel has become perhaps the most important European head of government – though also one of the most divisive/polarizing. In Germany, Merkel’s Eurozone crisis policy has been relatively popular, despite substantial opposition to the idea of German taxpayers ‘bailing out’ countries such as Greece and Spain. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM), which allows for loans up to €500 billion for member states of the eurozone in financial difficulty and in which Germany is the single largest contributor (27.1%), recently survived a judicial challenge and was confirmed by the Constitutional Court.

Between the 2009 federal election, which saw Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU form a black-yellow coalition with the free-market liberal Free Democrats (FDP), and the 2013 federal election last September in which Merkel’s CDU/CSU won a landslide result (41.5%) and formed a Grand Coalition with the Social Democrats (SPD), Angela Merkel’s popularity increased dramatically while that of the FDP collapsed just as dramatically. In the 2013 election, polls showed that Germans were particularly optimistic and upbeat about their country’s economic future.

Germany’s strong economic conditions are a result of structural factors (strong export market in Asia for German cars, machinery and equipment; specific demographic factors; Germany’s geographic location etc) and, Merkel’s critics point out, economic reforms undertaken by the red-green cabinet before 2005 (labour market reforms with Agenda 2010, cuts in welfare/unemployment benefits with Hartz IV). Some analysts worry that Germany’s current economic climate is not sustainable in the long term and warn that certain reforms must be undertaken if Germany’s economic health is to remain so strong in the next years. For example, Germany has a very low birthrate and skills shortage is a particularly big issue. The OECD has said that Germany will need to recruit 5.4 million qualified immigrants between now and 2025, and in August the government published a list of skilled job positions to recruit non-EU foreign labour. With the economic crisis, Germany has already welcomed thousands of southern European immigrants, particularly younger and educated citizens, fleeing huge levels of youth unemployment in Spain, Italy, Greece and so forth. Regardless, in the eyes of most voters, Merkel (and, by extension, her party) have come to stand for economic stability and growth in chaotic and uncertain times; a steady and reliable hand at the helm. Fairly or unfairly, the widespread perception in Germany is that Merkel is a strong and capable leader who has been a steady hand in turbulent waters, who has successfully protected Germany from European economic turmoils. In 2013, Merkel’s CDU played on her personal popularity, and ran a very ‘presidential’ campaign which heavily emphasized Merkel, and campaign posters drove the above ideas home: Merkel’s face with the words ‘stability’/’security’/’continuity’. Exit polls in 2013 showed that many of the Union’s voters said that their top motivator in voting for the CDU/CSU was Merkel alone (in contrast, only 8% of SPD voters said that their top motivator was the SPD’s disastrous top candidate in 2013, foot-in-mouth victim Peer Steinbrück).

Domestically, Merkel’s political longevity and her ability to destroy her junior coalition partners (the SPD from 2005 to 2009 and the FDP from 2009 to 2013) owes a lot to her local reputation for legendary fence-sitting and pragmatism. Merkel has often been perceived as lacking any ideological direction of her own, instead she has run things on the basis of shifting her policies and adapting herself to what was popular. After the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan in 2011, which reopened Germany’s very contentious nuclear energy debate, Merkel made a monumental U-turn and announced that Germany would shut down all nuclear reactors by 2022. Just a year before, her government had overturned a red-green decision to shut all reactors down by 2022. Strongly anti-nuclear public opinion, which threatened the CDU’s standings in crucial state elections in 2011, strongly pushed Merkel to do a 180 on the issue. Since then, Merkel and the CDU have promoted renewable energy, which is off to a tough start. A government renewable energy surcharge, which will increase electricity bills by about 20%, is unpopular (see this article in Der Spiegel for more on Germany’s energy transformation). In the 2013 election, there were few differences between the SPD and the CDU/CSU’s platforms, because the Union effectively blurred major policy differences between them on the SPD – the few differences concerned tax increases (the SPD and Greens supported tax increases for the wealthy, the Union rejected tax increases) and the universal minimum wage (the Union opposed it in the 2013 campaign, but didn’t care much about it in the end) – while they agreed on matters such as gender quotas in management positions, freezing rent, renewable energies and the bulk of EU policy (although Merkel reiterated her tough anti-Eurobond stance and strict application of the Fiscal Compact).

Already between 2005 and 2009, Merkel’s first Grand Coalition cabinet, the government’s policies had been quite moderate and even leaned towards the SPD on some issues (Keynesian-style deficit spending, healthcare reforms in a pro-public healthcare direction, VAT increase for infrastructure development, introducing legal minimum wages in some industries). The SPD did very poorly in the 2009 European elections, and a few months later it won a record low 23% of the vote in the 2009 federal elections. The SPD was unable to campaign on its significant achievements in influencing policy and tempering the CDU/CSU’s more right-wing policies while in the Grand Coalition; it bled votes to all sides (non-voters, Greens and the Linke being the top beneficiaries) as a result of strong voter discontent with Agenda 2010/Hartz IV. The SPD was badly hurt by Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s highly controversial welfare reforms, and it has torn between a desire to continue appealing to the centre as Schröder successfully did in 1998 and 2002 and an urge to move back towards the left following left-wing backlash to Agenda 2010 after 2004. The SPD’s platform in 2013 was quite left-wing – emblematic of the SPD’s post-Schröder swing to the left, the party being pushed to left as Merkel successfully adopted SPD planks and a general shift of all parties (except the FDP) to more leftist positions since 2009 and especially 2005. In 2013, the SPD’s support increased to 25.7% of the vote, but it remained miles behind the CDU/CSU. The SPD was unable to sucessfully challenge Merkel, even on her government’s weak suit – social justice, a major concern for German voters these days (or rather, while the SPD’s social policies were more popular, the SPD lacked the CDU’s credibility on Eurozone and economic issues) – and shackled with a poor chancellor-candidate (Peer Steinbrück, the infamous ‘gaffe-machine’).

Between 2009 and 2013, the FDP, Merkel’s junior partner after the 2009 elections – in which the right-liberal FDP, on a platform of low taxes and surfing on right-wing unease with the fairly moderate record of the CDU-led government between 2005 and 2009, won an historic high of 14.6% – collapsed. The FDP’s performance in the black-yellow government was widely judged, even by its 2009 supporters, to be ineffective and incompetent and their actions reinforced the old image of the FDP as an exclusive club for special interests and high earners. Merkel steamrolled the FDP and by not lowering taxes, she effectively drained the FDP’s main plank of all meaning. In 2013, therefore, the FDP’s calls for tax cuts certainly rang hollow. The party, which had been in every Bundestag since the end of the War, suffered a defeat of epic and historic proportions: 4.8%, falling below the 5% threshold for seats in the Bundestag and finding itself without any MPs. In past (and recent – Lower Saxony in 2013) federal and state elections, the FDP had survived ‘close calls’ thanks to ‘loan votes’ – CDU supporters voting (on their second, PR, vote in Germany’s two-vote system for federal and most state elections) for the FDP to allow the party, the CDU’s preferred coalition partner, to retain seats. Loan votes and locally-focused FDP campaigns had allowed the FDP to survive in several state elections after 2009 (even as the federal party was in full collapse mode), but these dynamics were in-existent or insufficient in September 2013 – after the Lower Saxony election in 2013, which saw the black-yellow government lose to red-green despite the FDP’s success, there was a backlash against loan votes for the FDP, based on the erroneous claim that black-yellow would have been reelected without the loan votes (however, exit polls in September 2013 showed that a bit less than half of the FDP’s voters were tactical voters). The liberal party has lost its raison-d’être in the eyes of many voters. In the past two decades or so, the FDP’s niche had been lower taxes. Having been utterly unable to deliver on the one issue which defined it and which attracted so many voters in 2009, the FDP lost all credibility and effectively a good chunk of its raison-d’être. The FDP effectively dropped/lost the issue of civil rights/individual liberties to the Greens (and now, the Pirates) in the 1990s after approving wiretaps and voting against civil unions, there is now a serious risk that the FDP has lost the taxation/small government/economic liberalism issue to the CDU and the FDP’s right-wing supporters have in part shifted over to the new, anti-Euro Alternative for Germany (AfD).

The AfD was founded in February 2013, mostly by ex-CDU academics and private sector figures. The AfD’s unifying plank is opposition to the Euro (but not, it insists, the EU) – Bernd Lucke, the party’s leader, argued that the Euro was unsustainable and that it should be scrapped. Economically troubled southern European countries should abandon the Euro while northern European countries including Germany and Austria could form a smaller Eurozone in the north. The AfD claims that is not against the EU, but the party wants to reduce the scope of the EU’s power and supranational aspects, opposes Turkish membership and is against taxpayer-funded bailouts. The AfD is a right-wing party, but it is not really clear what it really stands for. The party’s leadership is economically liberal (in the European sense), but the party’s membership is not quite as convinced by the leadership’s liberalism: members voted to oppose the EU-US free trade deal, despite support from the leadership. Some AfD members and candidates have shifted to the right and embraced social conservative and traditional Christian ‘moral values’, which has reportedly displeased some liberal supporters. The AfD has rejected claims that it is anti-immigration, but the AfD was the only major German party to praise the results of the recent Swiss referendum curbing freedom of movement. The party’s opponents on the left have accused it of pandering to anti-immigration and xenophobic sentiments. The AfD won 4.7% of the vote in the 2013 election, mostly protest votes which came, predominantly, from the FDP, other parties and Die Linke.

The AfD goes out of its way to promote a respectable and clean image of itself, rejecting ties and comparisons to right-wing populists and the far-right in other EU countries. Far-right parties such as the FN and Geert Wilders’ Dutch PVV tried to woo the AfD, but the Germans strongly rejected any cooperation with these less respectable, more extremist parties. It has even rejected overtures from UKIP, criticizing the British party’s anti-EU and anti-immigration stances; although it has been reported that some members of the AfD are supportive of an alliance with UKIP and its partners in the EFD group in the EP. Instead, the AfD has been trying very hard to be accepted as an ally of the British Conservative Party, to fit the general image of a respectable, rather moderate centre-right but Eurosceptic party (notwithstanding the Tories’ ECR ties to more inconvenient parties in Poland and the Baltics). The AfD’s campaign to woo the Tories, something welcomed by some Tory/ECR MEPs, to their side was complicated by Merkel and Berlin-London diplomatic channels. Merkel is said to have warned or pressured David Cameron against developing formal ties with the AfD. However, on June 12, the ECR group voted to accept the AfD, unofficially by a narrow vote of 29-26 in which 2 Tory MEPs defied Cameron’s wishes by voting in favour of the AfD. 10 Downing Street will hope that this embarrassing defeat for Cameron in ‘his’ EP group will not endanger his highly-important relationship with Merkel.

The AfD was joined by Hans-Olaf Henkel, a former president of the German employers’ federation (BDI) and manager at IBM Germany, in January 2014. An advocate for a division of the Euro between a stable northern zone and an unstable southern zone, Henkel was second on the AfD’s list for the EP behind party leader Bernd Lucke.

After the 2013 election, a Grand Coalition with the SPD was the only realistic option on the table. The only other coalition option was a black-green coalition, between the CDU/CSU and the Greens, but the federal Greens, who had ended up performing quite poorly in the election, had burned too many bridges with the CDU/CSU during their rather left-wing campaign. The Union and the SPD reached an initial agreement on a coalition program on November 27, but for the first time, one of the coalition parties – SPD – had taken the decision to submit any coalition agreement it would sign to ratification by its membership in an internal vote. On December 2014, with high turnout, 76% of SPD members voted in favour of the deal. The internal vote was a bit stacked in favour of the yes, because SPD leader Sigmar Gabriel put his job on the line and strongly promoted the terms of the Grand Coalition agreement. Furthermore, in the unlikely event that SPD rejected the agreement, there was the threat of snap elections (which the CDU/CSU would have won by a similar margin as in September 2013).

On the whole, the SPD got a fairly good deal out of the CDU/CSU, considering the weak bargaining position they were in. The new government’s policy program includes two of the SPD’s main promises from 2013: the introduction, from January 1 2015, of a universal minimum wage at €8.50 (with only minors, interns, trainees or long-term unemployed people for their first six months at work excluded; some companies will have until 2017 to phase in the new minimum wage) and allowing workers who have contributed for 45 years to retire early at 63 (currently 65). The SPD also won a liberalization of Germany’s dual citizenship laws, which will no longer require German born-children of non-EU/Swiss citizens to choose, at age 23 (provided they’ve lived in Germany for 8 years or graduated from a German school), between their parents’ and German citizenship. On economic matters, there will be no tax increases (a key CDU demand) but the government promises new investments worth €23 million in training, higher education, R&D and transport infrastructure among others. To please the CDU/CSU, the government’s pension reform also includes a measure to increase the pensions of older mothers who raised children before 1992. To please Bavaria’s CSU, the new government is supposed to implement a toll on foreigners using German autobahnen, but many doubt the controversial policy will go ahead given that Berlin needs to find a way to ensure that Germans don’t pay the toll and make it compatible with EU legislation. The new government is committed to the energy transition, to gradually wean Germany off of nuclear energy by 2022.

In the cabinet, SPD leader Sigmar Gabriel is Vice-Chancellor and minister of the economy and energy – responsible for the energy transition. Andrea Nahles, a former SPD general secretary from the party’s left, became minister of labour and social affairs, pushing forth the pension reform. In the CDU, the promotion to the defense ministry of Ursula von der Leyen, who had been labour minister under black-yellow, was widely read as a sign that Merkel was grooming her as a potential successor. Wolfgang Schäuble, the CDU finance minister since 2009 associated with austerity policies and Germany’s ‘tough’ line, retained his job. Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the SPD’s 2009 chancellor-candidate who is perceived as being pro-Russian, returned to the foreign ministry – a job he had held under the first Merkel Grand Coalition.

The coalition’s platform was criticized by employers, who were particularly up in arms about the pension reform – both the SPD’s retirement age changes and the Union’s pension boost for older mothers, which they claim will cost Germany €130 million by 2030. The conservative newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the tabloid Bild were both critical of the coalition agreement. Abroad, The Economist has criticized Merkel’s temerity and the lack of structural reforms, arguing that the government’s various interventionist mini-reforms risks squandering the country’s past economic progress.

The new government has been fairly quiet. In February, it ran into a mini-cabinet crisis following the surprise resignation of a SPD MP (Sebastian Edathy) who later fled the country after police searched his house and claimed that he was the client of a Canadian-based international child pornography ring. The CSU agriculture minister, Hans-Peter Friedrich, was forced to resign after it was revealed that, while interior minister in October 2013, he had informed Gabriel of an investigation against Edathy and in doing so likely breached an official secret. The SPD’s leadership is suspected of having tipped off Edathy (and prompting him to resign from the Bundestag before his parliamentary immunity was stripped), and the CSU demanded that the SPD’s parliamentary whip step down. Because of the CSU’s sabre-rattling, the Grand Coalition was briefly at risk of premature death, but the events in Ukraine in late February-early March 2014 meant that the scandal finally blew over. Federally, polling numbers have not budged much since September 2013: the CDU/CSU is down from 41.5% to about 39% in polls but still miles ahead of the SPD, which is stable at its 2013 levels. The Greens, who won only 8.4% in 2013, are now back up to 10-12%; Die Linke are in the 8-10% range, above their 2013 result (8.6%). The FDP is still dead, and the AfD would likely win seats in the Bundestag in the next election, because it’s now polling at 6-7%, above the 5% threshold in federal elections.

There was a major and significant change in the electoral system ahead of the EP elections: in February 2014, the Constitutional Court ruled that the 3% threshold was unconstitutional and ordered for it to be scrapped entirely. In 2009 and prior EP elections, a 5% threshold had applied, but it had been lowered to 3% by the major parties after the Constitutional Court had struck down the 5% threshold in November 2011. The new rules were obviously a huge boon for small parties – a category which now includes the FDP.

Merkel’s CDU/CSU emerged victorious in the EP elections, and Merkel expressed satisfaction with the Union’s performance and its majority over the SPD. However, with only 35.4% for the CDU and CSU, it is a poor result for Germany’s senior governing parties, which is down both from Merkel’s own landslide result in September last year (41.5%) and the Union’s result in the 2009 EP election (37.9%) and past EP results (2004 – 44.5%, 1999 – 48.7%, 1994 – 38.8%). In 2013, Merkel’s own personal popularity had been the reason for the CDU’s success and the party had likely received votes which went more to support Merkel the Chancellor than to support the CDU/CSU the party. Therefore, in an election without Merkel on the ballot, some loses could be expected.

The main reason why the Union parties did poorly is because the CSU’s result in Bavaria was unexpectedly bad: the ruling hegemonic party in conservative Bavaria received only 40.5% of the vote in the Land, down 7.6% from 48% of the vote in 2009 (and 49% in the 2013 federal election and 47.7% in the 2013 state elections, held a week before the federal election). The result came as a surprise, because state-level polling in Bavaria for the EP had showed the CSU in its usual high-40s territory, and the CSU had done fairly well (by Bavarian standards, which means winning in the usual landslide) in local elections held in the state in March 2014. Over the past few months, the CSU has grumbled against some of the government’s policies – Bavarian Minister-President Horst Seehofer, the powerful boss of the CSU and the state, opposes the construction of high-voltage power lines which would transmit wind energy from the North Sea to southern Germany, and the CSU has continued playing its populist, regionalist messages (against EU and federal bureaucrats, against foreign drivers clogging up Bavaria’s autobahnen, against immigrants receiving welfare benefits).

One reason for the CSU’s poor turnout may have been the low turnout – only 40.9%, which is about 7% less than in the country and actually down 1.5% from the last EP election in Bavaria. In contrast, turnout in the rest of Germany increased by 4.9% from 2009. There was, as in 2009, a clear correlation between higher turnout and local elections being held the same day – turnout was highest in the Rhineland-Palatinate, reaching 56.9%; it was up 16.8% from 2009 to 46.7% in the Eastern state of Brandenburg, where there were no local elections alongside the EP election in 2009. However, turnout is not the only explanation, because the CSU’s raw vote did not hold stable – the party lost nearly 330,000 votes from 2009. The CDU’s support increased in Baden-Württemberg, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (Merkel’s home state, where she did very well in 2013), Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. The CDU suffered substantial loses in Berlin (-4.2%, but turnout increased 11.5%), Hamburg (-5.1%), Hesse (-5.8%) and Schleswig-Holstein (-3.5%).

The SPD, in contrast, performed quite well – 27.3% is a significant improvement on the party’s last two disastrous performances in the EP elections (21.5% in 2004 and 20.8% in 2009, both of them historic lows for the SPD), and the SPD has increased its vote total from about 5.5 million to 8 million. Martin Schulz, the PES’ ‘presidential candidate’ and the SPD’s top candidate, likely accounts for (part of) this good result. An Infratest dimap exit poll showed that Schulz was the favourite EU Commission candidate in Germany over Juncker, 42% to 24%, and even received the preference of 23% of CDU/CSU voters. 76% of SPD voters said that Schulz was an important reason that they voted SPD, against only 55% of Union voters who said that Juncker was an important reason that they voted for the CDU/CSU. The SPD was criticized for an ad campaign which said that “only if you choose Martin Schulz and the SPD, can there be a German President of the European Commission”.

The SPD has also performed surprisingly well, so far, in the Grand Coalition (unlike in 2005-2009). So far, many of the new government’s popular policies – the minimum wage, the pension reform and the dual citizenship reform – all bear the SPD’s mark, a surprisingly good record for what is a weak junior governing partner. 59% of SPD voters were happy with the federal government’s performance, compared to 79% of CDU/CSU voters and 53% of all voters.

The Greens placed third, with 10.7% of the vote, which is down 1.4% on their record-high performance in 2009 (12.1%) but an improvement on the Greens’ poor result in last year’s federal election, when the party won only 8.4%. The Greens’ result in 2013 came as a shockingly bad underperformance by the party, which had been on an upswing since 2007 and especially since 2010-2011 (marked by the Greens’ victory in the 2011 Baden-Württemberg state elections, where the Greens overtook the SPD and the left won enough seats to form a green-red coalition with the Greens in the driver’s seat). The Greens ran a woefully bad campaign in 2013, unwisely seeking to put an emphasis on their left-wing (similar to the SPD, furthermore) position on economic/social issues (with tax increases which the Greens had lots of difficulty defending and framing correctly) rather than their niche environmental issues where the Greens are most popular and credible. The Greens’ left-wing oriented campaign, under Jürgen Trittin, aimed to deflect left-wing criticism that the Greens were just waiting to dive into a black-green coalition with the Union, but instead it just nudged the Greens way too close to the SPD in a position where they would not dare criticize the SPD’s failings (notably on hot-button transportation and infrastructure kerfuffles). The Greens were also hurt by controversies stemming from a terribly overblown faux-scandal about ‘veggie-days’ (allegedly a Green plan to ‘force’ meat-free days in public cafeterias, even though they already existed) and a difficult series of revelations from the Greens’ ties to the pedophile movement in their foundational years. Since the last election, the Greens have been rebuilding, but it’s been difficult. In the Infratest dimap exit poll, 81% of voters said the Greens lacked a strong leader and 70% said they had difficulty seeing what the Greens stood for.

Die Linke placed fourth, holding their ground from the last election and gaining votes thanks to the higher turnout. It was an average result for the party, a bit below its result from 2013 (8.6%). Die Linke had hoped to gain from the SPD’s participation in cabinet, and tried to target left-wing voters disappointed with the SPD’s participation or performance in the Grand Coalition government. However, unlike in 2009, Die Linke proved unable to benefit from the SPD’s government record, largely because the SPD has been performing reasonably well in government thus far. The party still has trouble breaking out of its peripheral role in the German political system: after the party effectively supported or accepted the Russian invasion of Crimea and opposed Ukraine’s “fascist” government, the prospect of participation in a leftist coalition with the SPD and the Greens distanced itself, because the SPD demand that Die Linke drops its most contentious foreign policy planks (opposition to NATO, Euroscepticism) in order to be accepted into government. Die Linke lost votes in its East German, ex-GDR strongholds – its support in the East fell from 23% to 20.6%, its worst result in the old GDR since the first post-reunification EP elections in 1994; but it gained support in the West, increasing from 3.9% to 4.5%. In 2013, the results had also shown a trend towards a more nationalized vote, with Die Linke slowly building a still very small but substantial electorate in the West while being on a net downwards trend in the East, where the party faces demographic problems (aging electorate, out-migration, more affluent East German cities and social changes in the old GDR) and intense competition for protest voters.

The AfD did well in East Germany (8.3%), better than in the West (6.8%). Overall, across the country, the AfD had an excellent result, with 7% of the vote and 2.070 million votes, up from 4.7% and 2.056 million votes in the 2013 federal election. The exit polls showed that the AfD’s electorate largely consisted of protest voters, with highly specific concerns – currency stability (a major issue for 41% of the AfD’s voters), social security and immigration (a major issue for 40% of AfD voters but only 13% of the broader electorate); the AfD’s voters also stand out of the German political mainstream by expressing negative views towards the EU, the Euro, the desirability of deeper European integration and being rather pessimistic about the economy. For example, while the electorate which voted on May 25 was by and large strongly pro-European (actually, even more-so than in the past), with only 16% saying that EU membership brought more disadvantages (compared to 44% who said it brought mostly advantages, up from 25% in 2010), 70% saying that EU countries should act together more often and only 20% saying that Germany should return to the Deutsche Mark; the AfD’s supporters took opposite views on these issues, with 44% (the highest of all parties, with Die Linke in second at 19%) of AfD voters saying that the EU brought more disadvantages, 67% saying that EU member-states should act more independently/alone, 52% saying the EU’s open borders are threatening German society, 39% wishing to return to the old currency (one will notice, however, that not even a majority of AfD supporters support dropping the euro) and 78% opposing bailouts for other EU member-states (compared to 41% of German voters). The AfD is already a very polarizing party: 47% of voters considered it a right-wing populist party, which is not a popular label to be identified with in Germany, and 41% said that while it did not solve problems “it called them by their names” (80% expressed similar views regarding Die Linke).

The AfD appears to be responsible for a good part of the CDU and CSU’s losses. Infratest dimap’s vote-transfer analysis has some suspect findings, but it reports that, compared to 2013, the AfD gained 510,000 more votes from the Union, 180,000 from the SPD and 110,000 from Die Linke; in 2013, the AfD had pulled a diverse electorate, although most of their voters came from the smoldering ruins of the FDP, Die Linke and other parties. According to the vote-transfer analysis from this year, the bleeding from the FDP to AfD was more limited (-60,000) – instead, we are told that the FDP lost a good number of votes to the SPD (60,000) and the Greens (40,000). The city of Munich (Bavaria) also conducted a vote-transfer analysis for the city, compared to the 2009 EP elections. In Munich, the CSU lost 21,100 votes – or 16% of its 2009 voters – to the AfD, providing the new party with its largest bulk of voters (smaller quantities came from the FDP – 2,200 votes; the FW – 2,400 votes; non-voters – 2,100 votes; and other parties – 1,800 votes). In Bavaria as a whole, the AfD did quite well, taking 8.1% of the vote, nearly doubling their percentage from 2013. It did best in Munich’s suburbs in Upper Bavaria and in Swabia. Interestingly, in Munich, the FDP lost most of its 2009 voters – 42% of them (or 22,500 votes) the SPD, which is more than a bit unusual given that, in 2013, the FDP had lost 38% of its voters to the Union and only 9% to the SPD.

The Infratest dimap vote-transfer analysis showed that the Union parties, compared to 2013, also lost heavily to the SPD (-340,000) and Greens (-270,000); the SPD suffered loses, from 2013, to the Greens (-110,000) and AfD, but made up for them by gaining from the Union and FDP; the Greens suffered minor loses (-30,000) to the AfD but gained 2013 votes from all parties, mostly the two largest ones; Die Linke lost substantially to the AfD but gained, weirdly, 100,000 from the Union and 50,000 from the SPD. The analysis reported by Infratest dimap on the ARD website (linked above) seems very suspect and incomplete, given that it makes no mention of 2013 voters who did not vote this time. The Munich analysis appears more reliable, and the comparison is being made to the same kind of election.

The new electoral rules allowed seven small parties to make their entrance into the EP. Besides the FDP, which won a disastrous 3.4% and lost 9 of its MEPs, the largest minor party to make it in were the Freie Wähler (Free Voters), a confederation of various community/local lists and independent candidates which are present throughout Germany but quite strong in Bavaria, especially in local elections. The FW are very hard to pin down ideologically, with an eclectic mix of socially liberal policies, conservative policies or economically liberal policies, and a heavy focus on issues such as direct democracy, local autonomy and local/parochial concerns. The FW have a soft Eurosceptic side. The FW have, as noted above, run in state elections across Germany, but the only region where they have achieved considerable success at the state level is in Bavaria, where the FW won 10% in 2008 and 9% in the 2013 state election. The party won 1.5% of the vote across Germany, and 4.3% in Bavaria (down from 6.7% in the 2009 EP election, where FW was led by ex-CSU maverick Gabriele Pauli). The FW broke 2% in BaWü and Rhineland-Palatinate, but were under 2% in every other state (they had some success in Thuringia and Saxony, but FW had next to zero support in the city-states, NRW, Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein). The FW’s new MEP, Ulrike Müller (a Bavarian state MP), is individually affiliated with the small liberal European Democratic Party (EDP) and will sit in the ALDE group. A sign of how local and candidate-based the FW’s support is: the FW’s best result in Bavaria came from the Oberallgäu kreise in Swabia (13.7%), where Müller is from. In 2009, the FW had done best around Fürth in Middle Franconia (where Pauli is from), and poorly in Upper Bavaria and Swabia.

The Pirate Party won 1.5% of the vote and one seat; that vote is up a bit from 2009, when the Pirates were just getting started, but actually down from the party’s results in the 2009 and 2013 federal elections (2% and 2.2%). The Pirates famously rode a brief nationwide wave of momentum following the 2011 Berlin state elections, but that collapsed beginning in late 2012, under the weight of controversies, small scandals, public scrutiny into the party and a perception of the party as a single-issue party with no positions on major issues. The Pirates are nowhere close to regaining lost support: they have serious internal conflicts (largely between moderate left-libertarians and far-left anti-fascist movements), the party’s membership numbers have declined quite significantly, As in past elections, the Pirates drew a disproportionately young, urban (and likely male) electorate: it did best in Berlin (3.2%) and its best results generally came from university towns, such as Darmstadt (Hesse), the district where the Pirates won their highest result this year (3.6%). Their sole MEP will join the G-EFA group, like the two outgoing Swedish Pirate MEPs.

The Tierschutzpartei (Animal Protection Party) is a small animal right’s party, founded in 1993, is fairly similar to the Greens but with the added weirdness and quirkiness which usually characterizes these specifically pro-animal parties. The party has no particular base in any state or region, and is generally a non-factor in elections (0.3% in 2013), but in low-stakes EP elections (it already won 1.1% in 2009), it appears to be able to gain a few extra votes across Germany because of its name (in these kind of elections, parties with non-controversial names or names like ‘family’ or ‘animal protection’ which are cute and friendly buzzwords, tend to have small boost which can bring them up over 1%). Indeed, the party’s support was evenly distributed throughout Germany, ranging from 1% to 1.8%. The party will join the GUE/NGL group.

The far-right neo-Nazi National Democratic Party (NPD), which did not run in 2009, won 1.3% and 1 vote (for Udo Voigt, the NPD’s crazy former leader who has praised Adolf Hitler and Rudolf Hess in the past). The NPD, which experienced a brief revival in the early 2000s which brought them into the state parliaments in Saxony and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, has been declining in recent elections. In 2013, the NPD fell to only 1.3%. The NPD, constantly under investigation by the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (to the point where the common joke is that most NPD members are actually police informants) and facing renewed calls for its banning, is also weakened by financial problems and very negative media coverage of the far-right with the trial of the National Socialist Underground (NSU) Nazi terrorist group. Nevertheless, the NPD retains a small base in the most deprived regions of East Germany, where the NPD won 2.9% of the vote (and 3.6% in Saxony). The NPD, like the Greek and Hungarian Nazis, are untouchable parties – the EAF, for example, rejected the NPD. Udo Voigt will sit as a non-inscrit.

The Family Party, a minor socially conservative Christian democratic party with a small traditional base of support in the Saarland, won 0.7% (which is actually less than in 2009) and qualified for one MEP, who will sit with the AfD and the British Tories in the ECR group. Like with the Animal Protection Party, the Family Party likely benefits in these low-stakes elections from its name, a cute and friendly buzzword. The Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP) is a Bavarian-based conservative green party (although it has shifted to the left recently, while retaining a ‘pro-family’ and socially conservative orientation unusual for the left-wing green movement), founded back in 1982 by right-wing socially conservative Green dissidents. The ÖDP has received a stable 1-2% of the vote in Bavarian state elections since the 1990s, but the party is largely absent from other states. In Bavaria, the ÖDP won 2.7% of the vote this year, up from 0.6% in 2009. It peaked at 6.7% in Memmingen. Outside Bavaria, the ÖDP’s best result seems to have come from BaWü (only 0.7%). The party’s new MEP will sit with the Greens. Finally, the last seat was won by an unusual party – Die PARTEI (literally The PARTY), a satirical protest party founded in 2004 by the editors of the satirical and provocative magazine Titanic. Die PARTEI often mocks the empty slogans and rhetoric of the major parties and calls major politicians ‘stupid’. The party’s most famous and long-lasting promise is to rebuild the Berlin Wall around East Berlin and the former GDR, a pledge which it has now amended to include building a wall around Switzerland (the party’s response to Switzerland’s recent referendum on freedom of movement). When the party is serious, its platform is usually quite left-wing. In this election, Die PARTEI also promised a ‘lazy rate’ (a quota for lazy people and loafers), redistributing all income over €1 million, abolishing DST, limiting executive pay to 25,000x that of the average worker, ‘fucking’ the US-EU FTA and changing the voting age so that only those between 12 and 52 can vote. Die PARTEI has small strongholds in left-wing inner city areas, those trendy and cosmopolitan urban areas where the Greens and Die Linke (in the West) do very well in. It won, for example, 3.8% in Berlin’s famous Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district and 4.2% in the inner-city Hamburg district of St. Pauli.

Die PARTEI has promised that its MEP will resign the seat monthly, so that every candidate on the list will get a chance to serve for 30 days in the EP. In between the satire, Die PARTEI has suggested that it may be looking into joining a group, perhaps the Greens-EFA.

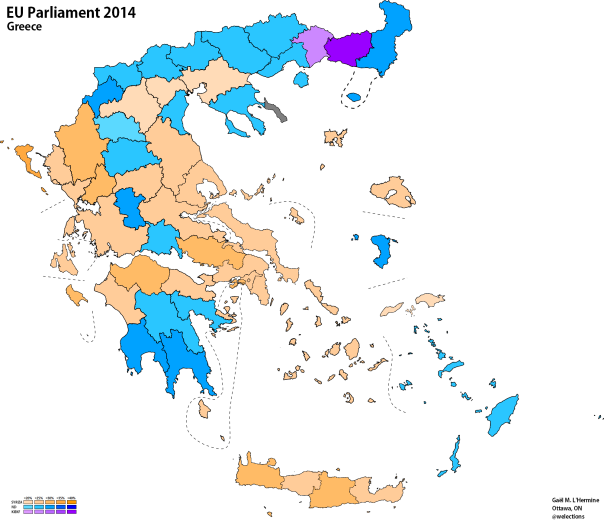

Greece

Turnout: 59.97% (+7.43%)

MEPs: 21 (-1)

Electoral system: Open-list PR, 3% threshold; mandatory voting (unenforced)

SYRIZA (GUE/NGL) 26.57% (+21.87%) winning 6 seats (+5)

ND (EPP) 22.72% (-9.58%) winning 5 seats (-3)

XA (NI) 9.39% (+8.93%) winning 3 seats (+3)

Elia (S&D) 8.02% (-28.63%) winning 2 seats (-6)

To Potami (S&D) 6.6% (+6.6%) winning 2 seats (+2)

KKE (GUE/NGL > NI) 6.11% (-2.24%) winning 2 seats (±0)

ANEL (ECR) 3.46% (+3.46%) winning 1 seat (nc)

LAOS (EFD) 2.69% (-4.46%) winning 0 seats (-2)

Greek European Citizens 1.44% (+1.44%) winning 0 seats (±0)

DIMAR (S&D) 1.20% (+1.2%) winning 0 seats (±0)

Union for the Homeland and the People 1.04% (+1%) winning 0 seats (±0)

Greek Hunters 1% (-0.26%) winning 0 seats (±0)

Bridges (ALDE) 0.91% (+0.91%) winning 0 seats (±0)

Greens-Pirates (G-EFA) 0.9% (-2.59%) winning 0 seats (-1)

Others 7.95% winning 0 seats (±0)

Greece has been at the centre of EU politics over the last five years, as the country which has suffered the longest and the most from the Eurozone debt crisis. As a result thereof, no EU member-state has seen political changes as radical as those which have taken place in Greece since 2009. The Eurozone crisis which has the leading issue in European politics for the past 4/5 years began in Greece shortly after the October 2009 legislative election in the country.

The root causes of the Greek (and, to a lesser extent, European) crisis were the country’s excessively high budget deficits and public debt. Since joining the EU in 1981 and especially since the mid-1990s, successive Greek governments customarily ran increasingly large structural budget deficits which by extension meant that Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio increased to reach unsustainable level by the time the 2007-2008 global recession triggered the economic and debt crisis in Greece. The crisis, however, was not caused – as is widely believed – by huge government expenditure or even a particularly generous welfare state (the popular ideas of lavish social benefits, ‘lazy’ Greeks not working hard enough and long paid vacations were largely myths) but rather by problems in the revenue side of the equation – tax evasion has famously been described as a ‘national sport’ in Greece, and the government’s unwillingness and inefficiency at collecting taxes has meant that the state has lost billions of euros in revenue. Greece’s tax evasion problem was compounded by a very large black market (about a quarter of the economy). Other factors which contributed to make the Greek debt crisis particularly catastrophic were the country’s very high external debt, a large trade balance deficit, heavy government borrowing and political corruption (since the restoration of democracy in 1974, Greece’s political system has been notoriously clientelistic).

By the time of the October 2009 election, Greece had already been in recession since 2008, its shipping and tourism industries having been hit particularly hard by the recession. The ruling conservative New Democracy (ND) party called early elections, which it lost to the opposition Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) of George Papandreou, the third generation in a long political dynasty in post-war Greece (his predecessor, ND leader Kostas Karamanlis, was also the son of a former Greek Prime Minister). Upon taking office, the new PASOK government revealed that the country’s deficit and debt was much worse than previously thought, with the deficit revised to be an alarming 15.7% of GDP and the public debt at 129.7% of GDP – Greece now had the largest deficit and debt-to-GDP ratio in the EU. Events accelerated in early 2010, as it became apparent that Greece was unable to borrow on the markets and was forced to asked for a loan from the EU and the IMF to cover its costs. Credit rating agencies, in April 2010, downgraded Greece’s sovereign debt rating to ‘junk’ while speculation on a potential default and exit from the Eurozone (a ‘Grexit’) ran wild. In May 2010, Greece was granted an initial loan of €110 billion from the ECB, EU and the IMF (a powerful trio which has become known in Greece and other countries as the ‘Troika’) in exchange for the approval of an unpopular austerity package by the government. The Papandreou’s May 2010 austerity package, the third set of austerity measures in only four months, included further cuts in public sector salaries, limits on employee bonuses, cuts in pensions and tax increases across the board (the VAT, luxury taxes, property taxes, excise taxes). However, initial austerity measures only worsened the economic crisis, while Greece became dependent on bailout funds to foot its bills and was thus forced to adopt a fourth austerity package in June 2011 to access the next installment of bailout funds. Despite massive protests and a general strike, the Papandreou government passed the new austerity package which now included a plan for privatizations (with a target of €50 billion in revenue), more tax increases and pension cuts.

Austerity measures adopted to meet the Troika’s strict conditions for the bailout had a disastrous impact on Greece’s economy and society, while doing nothing to turn the ship around – in fact, fears of a Greek default and ‘Grexit’ only increased in 2011. Greece, in recession since 2008 with a GDP shrinkage of 3.1% in 2009 and 4.9% in 2010, saw its economy shrink by a full 7.1% in 2011 and 7% in 2012. Unemployment increased from 10.4% in the last quarter of 2009 to 20.8% in the last quarter of 2011, and reached a high of 27.8% in the last quarter of 2013. Unemployment has hit young people the hardest, with over 60% of them currently unemployed. Major spending cuts have crippled Greece’s healthcare system (while unemployment left many without access to public healthcare), with most hospitals and the clinics in precarious conditions; the suicide rate has increased while there have been reports of an increase in HIV infection rates and a malaria outbreak for the first time in four decades. Greece’s public debt reached 148.3% of GDP in 2010 and 170.3% in 2011, while the budget deficit fell to 10.9% in 2010 and 9.6% in 2011

In October 2011, when an agreement on a second multi-billion euro bailout including a debt restructuring (a haircut of 50% of debt owed to private creditors), Papandreou shocked and seriously angered the Troika and EU leaders by announcing a referendum on the deal. Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy threatened to withhold payment of the next installment of bailout funds, and under intense EU, Troika and domestic opposition pressure, Papandreou was forced to renege on his idea and pushed out the door. A new national unity government led by an independent technocrat, Lucas Papademos, with ministers from ND, PASOK and the far-right Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS). Increasingly exasperated with what they saw as Greek politicians unwilling to implement the required austerity measures or being woefully ineffective at putting them in practice (for example, the government has missed privatization targets by miles for several years), the Troika – especially the Eurozone and Germany – became even tougher in their demands for austerity and economic reforms in exchange for a second bailout. In February 2012, to access the second bailout from the EU-IMF, Papademos’ government passed a fifth austerity package including tough cuts in the minimum wage, pensions, spending, the definitive elimination of a paid ’13th month’ salary, job cuts in the public sector, more privatization and structural reforms to liberalize ‘closed professions’. Despite major opposition from the streets, LAOS (which left government as a result) and over 40 dissident MPs from ND and PASOK, the austerity package was passed by Parliament and Greece was cleared to receive a second bailout of €130 billion with a debt restructuring agreement (worth €107 billion) with private holders of Greek debt to accept a bond swap with a 53.5% nominal write-off. Greece’s ten-year government bond yields shot through the roof at the time of the second bailout and debt restructuring, reaching nearly 40%.

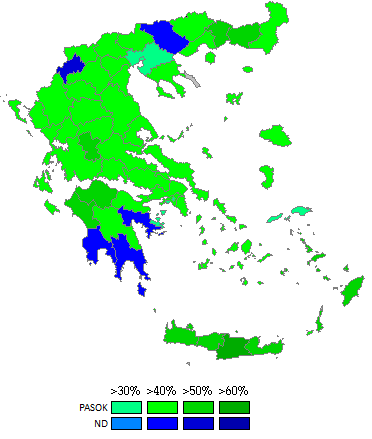

The economic crisis had huge repercussions on the Greek political system. Since 1981, Greece had a fairly stable party system dominated by two major parties – the conservative ND and the social democratic PASOK, although both were clientelistic patronage machines with a very strong dynastic tradition (both ND and PASOK were founded by prominent Greek dynastic politicians – Konstantinos Karamanlis for ND and Andreas Papandreou for PASOK) and rather different from the ‘average’ conservative and social democratic parties in Europe (if such a thing exists). PASOK, for example, lacks the trade union roots and ties or the Marxist background of many older social democratic parties in the EU. Although under Andreas Papandreou PASOK pursued a very left-wing re-distributive agenda and created Greece’s welfare state, PASOK can still be somewhat accurately described as the modern heir of Venizelism, a uniquely Greek liberal-nationalist ideology (it certainly inherited the Cretan stronghold of the Venizelists). After Andreas Papandreou’s death in 1996, PASOK progressively abandoned its early leftist, nationalist and Eurosceptic orientation, and both ND and PASOK became far closer ideologically than they would care to admit, although both remained bitter rivals because of tradition and political culture (with the exception of a brief period of instability and caretaker governments in 1989-1990, ND and PASOK had never governed together before 2011). At the helm of an increasingly unpopular government associated with austerity and the country’s economic collapse, the bottom fell out of PASOK progressively between 2010 and late 2011, and collapsed beginning in the fall of 2011, as Greece’s situation looked more desperate and catastrophic than ever before. ND’s support, in opposition under the leadership of senior politician Antonis Samaras, held up fairly well (albeit at historically low levels in the high 20s-low 30s) until early 2012. In opposition, ND hypocritically opposed the first three rescue packages in 2010 and 2011 (Dora Bakoyannis, a former foreign minister and Samaras’ rival for the ND leadership in 2009, was even expelled from the party in May 2010 for voting in favour of a EU-IMF loan; she went on to create her own pro-austerity liberal party, DISY); even under Papademos’ technocratic cabinet, ND tried to have the cake and eat it – Samaras promised to renegotiate the second bailout agreement after his party begrudgingly supported it, even if the Troika (exasperated by Samaras’ waffling and lack of commitment) made it clear that there could be renegotiation. In the Papademos government, both ND and PASOK (and LAOS, much to its chagrin) became associated with the unpopular austerity policies, which caused major internal dissent within party ranks.

The bankruptcy of the traditional political system allowed new parties – often quite radical – on the left and right to rise to prominence. On the left, the traditional third force in Greek politics has usually been the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), the country’s oldest parliamentary party. While the KKE’s electoral base is larger than that of many communist parties in the EU today, it has a very low ceiling because the party basically operates in an alternate reality – after the fall of communism, instead of evolving the KKE doubled-down on arcane and archaic quasi-Stalinist Marxist/Soviet rhetoric from the 1950s about the revolution, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. The KKE has successfully retained a loyal electorate, providing it with a fairly high floor but also a very low ceiling because the KKE’s rhetoric lacks credibility in practice (besides pretending that the Soviet Union and Joe Stalin are still alive and well). Although the KKE’s support rose to 12-14%, it never surged. Instead, the main beneficiary of PASOK’s collapse was the Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA), traditionally a rag-tag coalition of New Left parties and ideologies (eurocommunists from the KKE (Interior), a moderate 1968 splinter from the KKE; democratic socialists, eco-socialists, social democrats, left-wing Eurosceptics, Trotskyists) which enjoyed a late surge in early 2012 on the back of the popularity of the anti-austerity message of SYRIZA’s young leader, Alexis Tsipras. Although one might expect common ground, there is intense hatred between the KKE and SYRIZA (in fact, it often appears as if the KKE hates SYRIZA more than any other party, fascists included), with the former considering the latter as ‘opportunists’ and a ‘bourgeois front’ to trick ‘the proletariat’ into perpetuating capitalism (the KKE is anti-capitalist, anti-EU and anti-Euro). The Democratic Left (DIMAR), a moderate 2010 splinter from Synaspismós (the largest component in SYRIZA) with a nominally anti-austerity but pro-Euro platform, also tried to benefit from PASOK’s failings.

On the right and left, several parties led by anti-austerity dissidents from PASOK and ND emerged, although only one, the right-wing populist Independent Greeks (ANEL), a nationalist anti-austerity party led by ND dissident Panos Kammenos and created in February 2012, has been electorally successful. Kammenos is famous for his rabble-rousing nationalist (often anti-German) and anti-austerity rhetoric, with a certain penchant for tinfoil hat conspiracy theories and defamatory statements about his opponents (he has branded ND as ‘traitors’ for accepting the austerity memorandum and has been sued for libel/defamation several times).

On the far-right, the Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS) – a nationalistic, anti-EU and anti-immigrant party (one which also believed in 9/11 truther theories and was originally anti-Semitic) founded in 2000 – waffled over austerity, voting in favour in 2010 but against in 2011 before joining Papademos’ cabinet in late 2011 but leaving in 2012 by voting against the second bailout. LAOS’ indecision crippled the party, and provided a political void to be filled by Golden Dawn (XA). XA was founded by Nikolaos Michaloliakos in 1993, but until 2010, XA largely operated in the mysterious underworld of far-right/neo-Nazi activism and never won over 1% in any election, although XA’s violent street gangs were active and dangerous (in 1998, XA’s deputy leader killed a leftist student). XA’s first electoral success came in the 2010 local elections, in which the party won 5.3% of the vote and one seat (for Michaloliakos) in Athens. XA lies at the fringe of the far-right constellation in the EU: while it is an intellectually lazy trope to throw the word Nazi at all far-right parties, such a label is fully accurate for XA. Although the party has toned down the open Nazi fanboyism and admiration of the Third Reich which was a mainstay of XA in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Michaloliakos penned articles and essays which heaped praise on Adolf Hitler) and once in a while denies that it is Nazi, the party uses Nazi symbolism regularly (the party’s logo is similar to the Nazi Swastika, XA members have often given the Nazi salute, XA MPs wear Nazi symbols) and XA leaders and MPs continue to deny the Holocaust (Michaloliakos recently denied the existence of gas chambers and XA spokesperson Ilias Kasidiaris, who has a Swastika tattoo, denies the Holocaust and has quoted from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion) or use explicitly racist and anti-Semitic language (describing immigrants as sub-humans). Nevertheless, X also draws inspiration and ideological references from Greek history: Michaloliakos was briefly a member of EPEN, a far-right party founded by former dictator Colonel Georgios Papadopoulous (1967-1973), XA has praised the Colonel’s junta (the authoritarian military regime which ruled Greece from 1967 and 1974) and openly admires Ioannis Metaxas’ authoritarian-nationalist 4th of August Regime (1936-1940).

XA is radically anti-immigration – immigration has been an increasingly important phenomenon in Greece (and, nowadays, traditional Albanian immigration is slowly replaced by increased immigration from Pakistan and other Asian or African countries), and immigrants have been an easy scapegoat with the crisis (seen and depicted as stealing jobs from Greeks). XA called on the deportation of all immigrants from Greece while XA’s thugs have regularly beat up immigrants and non-whites. XA is also strongly anti-austerity, anti-bailout and anti-Euro; the party’s broader foreign policy expresses support for Greek irredentism and a very hardline stance on the Macedonian naming dispute. In a society marked by the breakdown of public services and increasing poverty, XA has built a strong grassroots support base by offering charitable and social services (food distribution, support for the elderly, protection for victims of crimes) explicitly reserved to Greek nationals or even XA members. In stark contrast to Golden Dawn’s “humanitarian” work, the party is distinguished from other far-right parties in Europe by its use of violence – XA’s blackshirt vigilantes and street gangs have regularly beaten up and assaulted immigrants and leftists (and often with the police’s silent acquiescence, given that the police is alleged to be tolerant or even supportive of XA) and Kasidiaris famously physically assaulted two left-wing MPs during a TV debate in 2012.

The May 2012 election was an ‘earthquake elections’ which saw the old political system destroyed and several new forces achieve remarkable success. ND won only 18.9% of the vote, the party’s worst result in its history, although it still topped the poll in an extremely exploded and fragmented political scene. On the left, PASOK collapsed into third place, winning only 13.2% of the vote – over 30% lower than in 2009. Left-wing (or far-left) anti-austerity SYRIZA replaced PASOK as the main party of the left, with 16.8% of the vote (a remarkable result for a party whose original ceiling was 5%); KKE, on the other hand, won a decent but comparatively paltry result of 8.5% (only a 1% improvement on its 2009 result and nowhere near the KKE’s historic highs). ANEL won 10.6%, making it the fourth largest party. XA surged to 7% of the vote and 20 seats, while LAOS’ support collapsed to 2.9% and it lost all 15 of its seats. DIMAR won 6.1% of the vote. In addition, the parties below the 3% threshold combined to win 19% of the vote (more than the largest party!), divided between greens (2.9%), three unambiguously pro-austerity and right-wing liberal parties (including DISY, 2.6%), far-left outfits and Greece’s hilariously fragmented communist parties. Even with Greece’s 50-seat majority bonus for the winning party (which historically provided one-party absolute majorities), no party or obvious coalition came close to commanding support of a majority of Parliament – Samaras, Tsipras and PASOK leader Evangelos Venizelos (Papandreou’s former leadership rival and his last finance minister) all quickly failed in their bids to form governments and there was no solution but to call for new elections in June.

The June elections quickly polarized into a contest between ND and SYRIZA, erroneously simplified to a ‘referendum on the Euro’ (implying that a SYRIZA government would default and withdraw from the Eurozone, which may have been the case but SYRIZA claims to support Eurozone membership and the EU in the abstract) or perhaps more accurately a ‘referendum on austerity’ (although ND didn’t campaign on austerity per se, it was widely understood to be a vote ‘in favour’ of the memorandum conditions). EU leaders quickly made clear that Greece would either need to respect the second bailout deal and associated austerity or be compelled to default and withdraw from the Eurozone – therefore voting for SYRIZA became a double-edged sword: a vote against austerity (SYRIZA promised growth through consumption, tax increases on the rich and businesses, raising social benefits and wages and nationalization of banks and strategic sectors; it also said it would suspend loan repayments until growth returned and would renegotiate the interest due) but also a high likelihood of a messy default and ‘Grexit’ (which, most predicted, would have wreaked havoc and thrown Greece into an even deeper depression). In the high-stakes contest, both ND and SYRIZA saw their support increase: ND won the election with 29.7% and 129 seats against 26.9% and 71 seats for SYRIZA. All other parties except DIMAR lost votes: PASOK receded even further to 12.3%, ANEL lost over 3% and fell to 7.5% and the KKE collapsed, losing 4% and winning only 4.5%. XA’s support proved surprisingly resilient despite intense media focus on the party, holding 6.9% of the vote. DIMAR won 6.3%. Parties below the 3% threshold fell to only 6%, with severe loses for the liberal right (DISY allied with ND, a liberal DX-Drasi won only 1.6%), LAOS, the Greens and the far-left.

ND and Samaras were able to form a ‘pro-memorandum’ and ‘pro-Eurozone’ cabinet with the support of PASOK and DIMAR (the latter, a small centre-left party, criticized SYRIZA for not giving guarantees on continued Eurozone membership and sought a national unity coalition), although at the outset both PASOK and DIMAR declined to directly participate in the government itself and instead opted to propose independents and technocrats for their portfolios (in other words, let ND deal with most of the crap). The finance ministry went to Yannis Stournaras, an independent economist.

Samaras’ government came in facing a new crisis: the Troika was demanding that Greece find a further €13.5 billion worth of austerity savings (spending cuts and tax increases) for them to release the scheduled disbursement, while Athens asked for a two-year extension of the deadline for the country to be self-financed (out of the bailout). The Troika, especially the EU and ECB, were in little mood to be accommodating, judging that Greece had failed miserably at implementing past legislated reforms and often exasperated at Greek politicians’ behaviour. Within the government, Stournaras (and Samaras) found themselves somewhat undermined by PASOK and DIMAR, which at times were more interested by their own political calculations (in PASOK’s case, a desperate bid for survival) while DIMAR quickly became rather reluctant to support tough austerity measures. As in the last Parliament, the need for further austerity measures divided the major parties and have steadily reduced the sizes of the ND, PASOK and DIMAR from their election day levels. On November 7, the Parliament approved the sixth austerity package (despite protests, DIMAR’s abstention and some dissidents from ND and PASOK), with €13.5 billion in cuts and tax hikes between 2013 and 2016. The package included more cuts on pensions, salary cuts (for public servants, academics, judges, doctors), cutting 110,000 public sector jobs by 2016, an increase in the retirement age from 65 to 67 and capping earnings in parastatals. In exchange, the Troika agreed to reschedule Greece’s debt and grant Athens two more years to reach a primary budget surplus of 4.5% of GDP.

Some economic indicators showed a very minor improvement in 2013, although unemployment hit a record high of nearly 28% (up from 24% in May 2012) and the public debt further ballooned to 175.1% of GDP (but should now begin falling, to 154% of GDP in 2017). Nevertheless, the recession was ‘less severe’ as the economy shrank by ‘only’ 3.9% in 2013 compared to 7% in 2012. The budget balance was -12.7% in 2013, due to the one-off costs of bank recapitalization, but Greece posted its first structural budget surplus in 2013 (+2% of GDP). Tourism was good in 2013, and the economy is expected to grow for the first time since 2007 in 2014, with a 0.6% growth rate in 2014 and 2.9% in 2015 according to EC estimates. The government’s structural reforms and labour market reforms have been said to significantly improve the ‘ease of doing business’ in Greece, although foreign investors remain very slow to test the waters. Unemployment has declined slightly to 26.8% in March 2014 and the EC projects it will fall to 24% in 2015. Yields on ten-year bonds have fallen below 8%, from a peak of well over 40%. In April 2014, Greece returned to the international bond market after four years with a €3 billion issue of five-year bonds. Nevertheless, the recovery remains very slow and extremely fragile. Furthermore, when it comes, it will take years for Greece to recover fully from a six-year long recession – for example, Greece’s nominal GDP is now €181.9 billion compared to €233.2 billion pre-crisis, in 2008. The crisis and austerity have pauperized a very large share of the population, with estimates that about 35% of the population lives in poverty or a precarious situation. The recession has wiped out millions of jobs, shut down thousands of businesses, put over three-fifths of young Greeks out of work (and forced thousands to emigrate to Germany and other countries) and public services will likely be in ruins for years.

The Troika has warmed up to the Greek government and Samaras (whom they initially disliked for his behaviour while in opposition and his reckless talk of renegotiating the bailout), and, prodded by the IMF, has come around to accept that Greece will not be able to repay all the money it owes. However, the government has continued to be weakened by corruption/tax evasion cases and difficulties at implementing its reforms. Since 2012, the government – and PASOK – have been embroiled in a corruption/tax evasion case surrounding the handling of a list with the names of thousands of suspected tax evaders, which France had handed over to the PASOK government in 2010. Now, former PASOK finance minister Giorgos Papakonstantinou is alleged to have removed the names of three family members from the list before transferring its contents to a USB while the tax authorities never received instructions to further pursue the investigation. Papakonstantinou faces a parliamentary inquiry. Evangelos Venizelos, PASOK’s current leader (and foreign minister since June 2013), who was finance minister from 2011 to 2012, is said to have kept the USB in his drawer for more than a year before sending it to Samaras and Stournaras. The government’s privatization program has continuously failed to meet its targets. They managed to sell Opap, the state gambling monopoly, to a consortium of Greek and east European investors but a Russian Gazprom bid for DEPA, the natural gas monopoly, fell through. This means that Greece has failed to meet the original privatization target of €50 billion and has been forced to scale back its privatization goals repeatedly. Greece still faces funding gaps in 2014 and 2015, requiring more bailout funds. Since late 2013, there has been talks in high circles that Greece will need a third bailout.

In June 2013, Samaras unilaterally and peremptorily closed down ERT, the state broadcaster, and sacked its 2000+ employees; announcing that a much leaner organization will replace it. The government’s decision, likely made to impress Troika inspectors. Six days later, the Council of State suspended the government’s decision to interrupt broadcasting and shut down ERT’s frequencies while rebel journalists continued operating a rump channel on other frequencies. Although ERT was widely described as corrupt, mismanaged and politically subservient; Samaras’ unilateral decision, which was opposed by PASOK and DIMAR (in fact, only XA and LAOS supported the government’s shutdown of ERT), provoked a firestorm of opposition. DIMAR decided to withdraw from government in late June 2013, prompting a cabinet shuffle which saw PASOK politicians enter cabinet – with Evangelos Venizelos as deputy Prime Minister and foreign minister.

In late 2013, Parliament narrowly approved a 2014 budget with further austerity measures and a controversial new tax package and in March 2014, it approved structural reforms. In both cases, the government’s majority in Parliament was extremely narrow – at about 152 to 153 votes, just over the absolute majority threshold (151) and always vulnerable to more dissidents. SYRIZA has been clamoring for early elections for quite a while now, and may finally get its chance next year: in early 2015, the Parliament must elect a new President, a procedure which requires a three-fifths majority on the third ballot (two-thirds on the first two ballots), and if this majority is not met, mandatory new elections are held for Parliament. Together, ND and PASOK only have 152 seats left, in addition to 13 from friendly DIMAR and a large number of various dissidents sitting in a 17-strong independent caucus and 6 miscellaneous unattached independents. SYRIZA has said that it will not support any candidate for President, and if he and other parties (ANEL has never missed an opportunity to help SYRIZA undermine the coalition, while XA and the KKE would never offer support) and independents deny the government a 180-seat majority to elect a consensus president, new elections would be held by March 2015. The government insists that it will see Parliament to the conclusion of its constitutional term in 2016, but its majority is very shaky.

In a bid to increase its credibility and international support, SYRIZA leader Alexis Tsipras has attended several conferences and left-wing political rallies across the EU, becoming the posterchild for the EU’s fledgling anti-austerity and anti-neoliberal radical left. At home, SYRIZA has merged its many components in a single party (there was some question from the election law whether or not SYRIZA as a coalition rather than a united party would have been eligible for the 50-seat majority bonus at the polls) and broadened its base, welcoming ex-PASOK members or improving ties with Greece’s powerful Orthodox Church (still considered as the official religion and prominent in education). SYRIZA has not moderated its rhetoric, opposing austerity – promising to break ties with the Troika, audit Greece’s debt, undo many reforms and privatizations while still reassuring foreign audiences that SYRIZA does not want to leave the Eurozone. The KKE has continued to exist in its alternate reality, waging a war of words against SYRIZA (described as opportunists ‘making a systematic effort to rescue capitalism in the eyes of the working people’).

XA’s support has increased in polls since the last election, polling up to 15%. The party’s activities – charitable, violent and cultural (nationalist/fascist torch-lit rallies) – increased in 2012 and 2013, but the government, police, judiciary and Parliament dragged their feet on the question of XA – hesitating over which attitude to adopt against XA’s racist violence, hate speech (Holocaust denialism) and criminal activities. In September 2013, anti-fascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas was murdered by an XA member in Athens, unleashing a wave of condemnation from all parties (XA included) and the government, and finally pushed Samaras to take stronger anti-fascist/anti-XA stances. A police crackdown led to the arrest of several XA members, including XA leader Nikolaos Michaloliakos, who remains in jail awaiting trial. Prosecutors are attempting to connect XA’s leadership to activities including murder, attempted murder, explosions, possessing explosives and robbery.

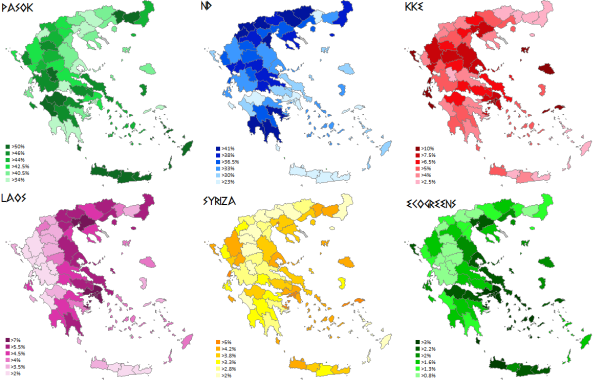

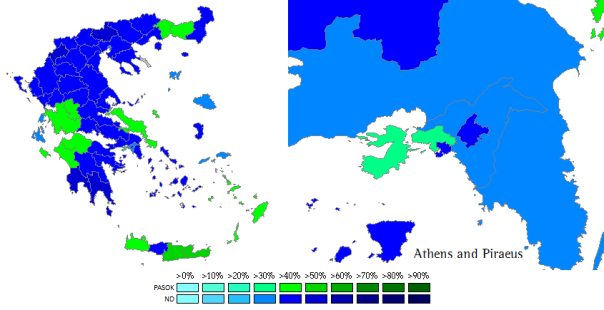

The EP elections were therefore fairly important in Greece, and they were tied to the runoffs in local and regional elections (the first round of those elections was held on May 18). SYRIZA topped the poll, as had been widely expected, with 26.6% of the vote, a result which is just below the party’s result in June 2012 (26.9%) and over 100,000 votes lower (turnout dropped from 62.5% to 60%, SYRIZA’s vote from 1.655 million to 1.518 million). While SYRIZA has been tied with ND or narrowly ahead in most polling for the next general election, the party has generally to consistently improve its predicted vote share on its June 2012 result. This may indicate that SYRIZA hit its new ceiling in June 2012, and now struggles to attract new voters from the rank of non-voters (the turnout in the EP election was high, but it was at an all-time low in June 2012) or other parties (the KKE has slightly improved on its disastrous 2012 result, to 6-8%, while DIMAR will likely fall below the 3% threshold in the next election). In the new open list system, SYRIZA’s most popular candidate (and MEP-elect) was 92-year-old war hero Manolis Glezos, who famously tore down the Nazi flag from the Acropolis in 1941 and then became a persecuted and later exiled icon of the Greek left. Since 1974, he has been a leftist writer and active in politics (for PASOK in the 1980s and Synaspismos/SYRIZA since the 2000s). He won more votes (448,971) than any other candidate.

ND, the senior governing party, did very poorly with only 22.7% and a bit less than 1.3 million votes, down from 29.7% and 1.825 million votes in June 2012. ND continues to poll much better – about at its 2012 levels or slightly below – in polling for the general election, but it may have done poorly at the EP and local elections as voters felt freer to oppose the government (without risking anything). Its coalition partner, PASOK, disguised itself as Elia (‘The Olive Tree’), an electoral alliance of PASOK and several new small parties (such as Agreement for a New Greece and Dynamic Greece, two small parties founded by former PASOK members). It won 8% and fourth place, down from 12.3% for PASOK in the last general election and a loss of nearly 300,000 votes. Nevertheless, 8% for Elia turned out to be a surprisingly strong performance from the moribund PASOK, which is polling at about 5-6% in national polls. Yet, a bad result is still a bad result, and PASOK leader Evangelos Venizelos’ hold on the fractious party was weakened by the weak result. Former Prime Minister George Papandreou, still a PASOK MP, seems to be organizing opposition to his old rival within PASOK, and Papandreou is said to have opposed PASOK’s transformation as Elia.

Some of PASOK’s lost support likely went to To Potami (The River), a new centre-left and pro-EU party founded in February 2014 by journalist and TV personality Stavros Theodorakis. The party can be placed on the centre-left of the spectrum (its MEPs have joined the S&D group, after hesitating with ALDE and the Greens) and it professes to be pro-European, but a lot about the new party is very vague – most of its talk revolves around meaningless buzzwords about reform, change and bland centrism/progressivism. Theodorakis toured the country with his backpack and gave low-key speeches on topics such as meritocracy and tax evasion. There have been claims that To Potami is financed by business interests to deny SYRIZA victory in the next elections, but Theodorakis denies such allegations. His party won 6.6% and two seats. The party did best in Crete (10.1%), an old Venizelist PASOK stronghold which has moved firmly into SYRIZA’s column since June 2012.

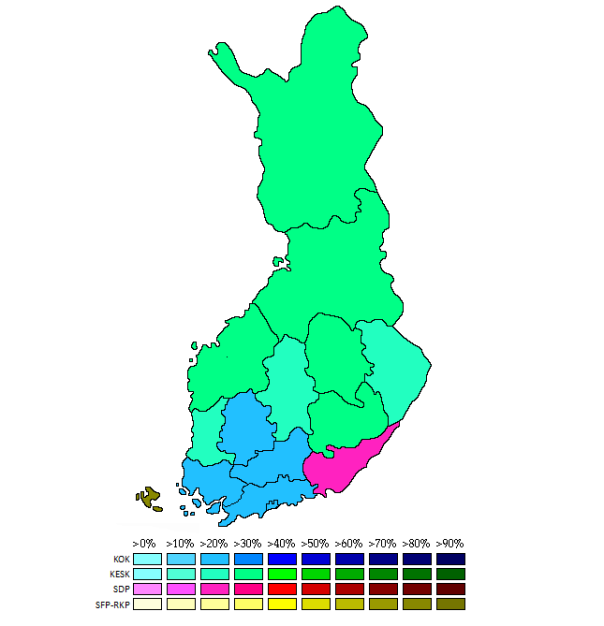

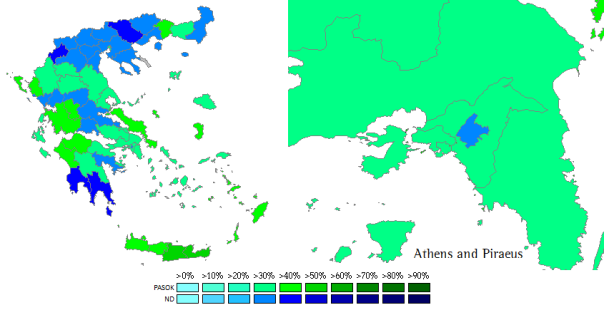

XA did very well, winning third place with a record 9.4% and 536,910 votes – in both cases, a marked improvement on its June 2012 result (6.92% and 426,025 votes). Although it no longer polls in the double-digits since the murder of Pavlos Fyssas and the crackdown on XA, the party has further expanded its base and retains a potential of up to 15-20% (based on polling regarding voters’ attitudes towards XA). Although the literature has often focused on XA’s activism in the populous central urban region of Attica (Athens-Piraeus), XA’s electorate is spread out across the country – it won 9.8% in the region of Attica (with results over 10% in all urban and suburban electoral districts of Athens and Piraeus) but its best prefecture was Laconia (15.5%), an old conservative stronghold in the southern Peloponnese, followed by the conservative Macedonian prefectures of Kilkis (13%) and Pella (12.8%).