Poland 2011

Legislative elections were held in Poland on October 9, 2011. All 460 members of Poland’s lower house, the Sejm and all 100 members of the upper house, the Senate, were up for reelection. The Sejm’s 460 members are elected through d’Hondt proportional representation with a 5% national threshold in 41 multi-member constituencies (each with a varying number of seats, peaking at 20). Ethnic minority candidates, which in practice means the German Minority party, is exempt from this 5% national threshold. A novelty in this election, the Senate’s 100 members will be elected through FPTP in 100 single-member constituency rather than by plurality block voting in multi-member constituencies as in the past. The Polish Senate is basically powerless, given that the Sejm can overrule any senatorial amendment or rejection by an absolute majority.

Poland has been governed since the 2007 legislative elections by Donald Tusk of the centre-right liberal Civic Platform (PO) with the whorish-agrarian Polish People’s Party (PSL) as its junior ally. Since 2010, the PO has also held the less powerful presidency with Bronisław Komorowski as President. Poland’s political landscape since the fall of communism in 1990 has been unstable and saw governments come and go, and political parties emerge and die off in quick succession. In 1997, the right-wing AWS won the elections with 33.8% but lost all 201 seats four years later in 2001 when it won 5.6%. That same year, the Polish left (SLD) won a landslide with 41% of the vote. Then, four years later, after a succession of scandals and an unpopular economic policy, the SLD collapsed to 11.3%. Since 2005 or so, the political system has stabilized somewhat with the emergence of the liberal Civic Platform (PO) and the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) as the two largest parties. Of course, since 2007, the two far-right parties which were so strong in 2005 – Andrzej Lepper’s Samoobrona and the League of Polish Families (LPR) – have collapsed into oblivion. But PO and PiS have implanted themselves solidly as the two main parties, with the SLD and PSL on the sidelines, distant thirds and fourths.

The 2005 legislative elections were won by PiS, led by Jarosław Kaczyński, whose twin-brother Lech Kaczyński won the presidential elections a month later. Between 2005 and 2007, PiS formed a fractious and fledgling coalition with the two far-right parties, Samoobrona and the LPR. After Jarosław Kaczyński’s coalition collapsed in 2007, the PO won the snap elections by a wide margin over PiS – 41.5% to 32% – while the far-right barely polled 3% altogether. Donald Tusk, PO’s leader and the runner-up in the 2005 presidential election, became Prime Minister in coalition with the agrarian PSL, an empty shell led by former Prime Minister Waldemar Pawlak which whores itself to the largest party in a bid to enter government.

Polish politics have seemingly stabilized, for the time being, into a system with two strong right-leaning parties, PO and PiS, a weak left and an in-existent radical left or right. From a cursory point of view, both PO and PiS are right-wing parties, but in reality PO and PiS are two very different parties both reflecting the polarized nature of Polish society and politics. The liberal PO reflects the pro-European, internationalist, liberal and comparatively secular vision of society shared by one half of Poland, that is the more urban and more affluent Poland. The conservative PiS reflects a Eurosceptic, deeply clerical, socially conservative and very nationalist vision of society held by the other half of Poles, that is the more rural and less affluent Poland. On moral issues, PiS is the most vocally socially conservative force though PO is not by any means a social liberal party. On economic issues, at least in rhetoric, the conservative PiS is far more dirigiste and in favour of state intervention than the liberal PO, which originally supported a flat tax, radical red-tape trimming measures and privatizations.

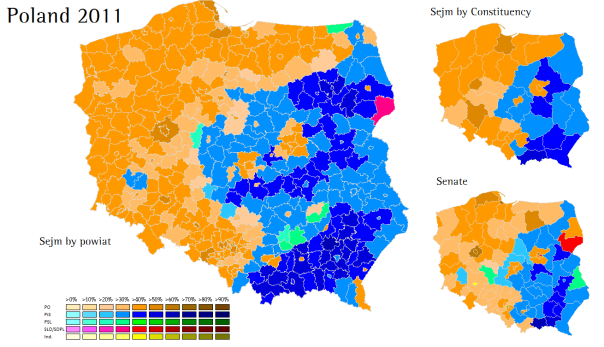

The polarized state of Polish politics is reflected by the electoral map of Poland, relatively stable since the 2005 presidential election. PO is very much a urban party, while PiS is very much a rural party. But the map also famously and very closely replicates the boundaries of Poland in 1914: the parts of Poland which were part of the German Empire until 1918 lean to PO, while the parts of the country which were part of the Russian Empire or of Austria-Hungary lean to PiS. It is not just a coincidence of history, but very much an effect of Polish history since 1918. German Poland was far more industrialized, urbanized and developed than either Russian or Austrian Poland. The railway network was far denser, industries (shipbuilding, coal mining) far more important and education levels higher. Far more importantly however, what is today western Poland saw major population shifts following World War II and the creation of modern Poland within its modern boundaries. German populations who lived in what is today Polish territory were forcibly moved to Germany and the territory resettled by Poles from other regions (the parts of interwar Poland seized by Stalin in 1945). Most of the Polish population in western Poland or the “German Poland” of 1914, has only been settled there for roughly 65 years at most. It is thus far less rooted locally, in most cases few have longstanding family ties with the region and is more accustomed to moving around. It is also a region where the new Polish communist regime post-war was able to set up its own state structure and institutions without running into any long-standing clerical hegemony. All these factors – economic development, affluence, new population with little local ties and a weaker Church – inform a more liberal view of society. In contrast, the rural regions of eastern Poland which were under Russian or Austrian control until 1918, have been ethnically Polish for hundreds of years and saw little population displacement in the post-war era. The population of rural Masovia or Galicia has been settled in those regions for hundreds of years, and the Catholic Church has retained a predominant influence even throughout the communist regime. Under Russian and Austrian rule, these poor rural regions were far less developed, industrialized or educated than German Poland, and to this day these regions remain poorer and less developed (far more rural and agriculture-based).

PO was elected on a very liberal program in 2007: flat tax (15%), privatizations, cutting red tape and other liberal-minded economic and fiscal reforms. In power however, Donald Tusk’s government was strayed away from any too radical measures and basically disowned economic liberalism. There is no flat tax in sight, taxes increased slightly, privatization has gone forward at a very slow and cautious pace and public spending remains high. The government can pride itself with having kept Poland out of recession in 2008, and the country’s GDP grew by a solid 3.8% in 2010 and is projected to grow at a similar rate in 2011 and 2012. Unemployment has fallen to 9% from a high of 20% in 2002. Salaries and the standard of living have also increased. The country’s debt remains an issue (it has increased to 56% of the GDP since 2007), and reforms in bureaucracy and the healthcare system remain overdue. In power, Tusk has aimed for consensus and unity as much as possible, which is why he has kept away from the PO’s original ideology of economic liberalism. He has attracted defections from the SLD and from some ex-PiS moderates. On economic matters, PO’s 2011 campaign lacks all the grandiose liberal rhetoric of 2007 and instead keeps to cautious rhetoric about Poland’s economic vitality and progress since 2007. No tax cuts are promised, though a cut in the VAT by 2014 is vaguely promised. The cabinet wishes to control the public debt by bringing it down to 48% of the GDP by 2015. Furthermore, the government wishes to inject more private competition in the healthcare sector. On the foreign stage, the Tusk government has also been all about conciliation and dialogue and has broken with the aggressive conspiracist-nationalistic tone of PiS which likes to play on lingering anti-Russian and anti-German sentiments common to Polish conservatism. This conciliatory style may have kept PO strong since 2007, avoiding the usual fate of collapse which has awaited most Polish governments, but it has given it the image of a wobbly party which is all about dancing in circles around a bonfire rather than actually taking tough decisions or deciding on policy.

In the 2010 presidential election, held in the wake of the death of President Lech Kaczyński, Jarosław Kaczyński postured himself as some kind of moderate and conciliatory figure. It won him 47% in the runoff, but he did not win the presidency. He dropped his new-found moderation and turned into a nutjob. He has said that his moderate positions in 2010 were caused by some prescription drugs he had been taking, and since then he has endorsed the anti-Russian conspiracy theories surrounding his twin brother’s death in the Smolensk plane crash and moved PiS even further to the right. In late 2010, a group of moderates and liberals within PiS including Joanna Kluzik-Rostkowska and Michał Kamiński left PiS to create the right-wing Poland Comes First (PJN), which has taken liberal positions on economic issues (criticizing the slow pace of economic liberalization under PO) but has otherwise struggled to differentiate itself from PiS. PJN itself descended into infighting recently when Kluzik-Rostkowska left the party to join PO. PiS campaigned on a populist economic platform, proposing to tax the banks, increase taxes on the wealthy, increase the minimum wage by 50% and halting the PO’s privatization.

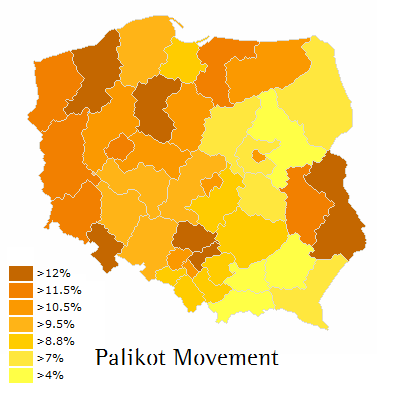

In the 2010 presidential election, the SLD’s presidential candidate and party boss Grzegorz Napieralski had won a surprisingly decent 13.7%. The left (running as LiD, a short-lived alliance of the left including the SLD) had failed to gain ground in 2007, but following PiS’ gradual shift to the right, there was a chance that SLD could improve its standing significantly in 2011 and place it in a position to re-establish itself and the Polish left as a real alternative. However, Napieralski’s success in 2010 apparently got to his head and he increasingly asserted his authority through a centralization of power within the party. He sidelined some influential members of the SLD during the creation of the party’s electoral slates in the constituencies. Starting in mid-September, the SLD faced competition from a new factor, the Palikot Movement (RP). The Palikot Movement emerged in 2010 as a cult around its eccentric founder, Janusz Palikot. Palikot, a social libertarian, had been an eccentric maverick member of PO and was known in Poland for his controversial statements on other politicians or his behaviour in general. Palikot, however, managed to turn what was until September a small personality cult into a real party (helped by the SLD’s divisions and a series of bizarre and provocative statements by the Church). The RP is a rarity in Polish politics: it is very socially liberal (pro-choice, pro-gay right, pro-drug legalization) and radically anti-clerical (which is rare in Polish politics). It combines social libertarianism with some kind of more vague economic liberalism.

Turnout was 48.92%, down from a high of 54% in 2007.

PO 39.18% (-2.33%) winning 207 seats winning (-2)

PiS 29.89% (-2.22%) winning 157 seats winning (-9)

Palikot 10.02% (+10.02%) winning 40 seats (+40)

PSL 8.36% (-0.55%) winning 28 seats (-3)

SLD 8.24% (-4.91%) winning 27 seats (-26)

PJN 2.19% (+2.19%)

KPN 1.06% (+1.06%)

PPP 0.55% (-0.44%)

WP 0.24% (+0.24%)

German Minority 0.19% (-0.03%) winning 1 seat (nc)

Samoobrona 0.07% (-1.48%)

The composition of the Senate:

PO 63 seats (+3)

PiS 31 seats (-8)

PSL 2 seats (+2)

Independents 2 seats (+2)

SLD-Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz 1 seat (nc)

SDPL-Marek Borowski 1 seat (+1)

Donald Tusk’s PO government made history on Sunday by becoming the first Polish government since the fall of communism to win reelection. His PO/PSL coalition has 235 seats, a 4-seat majority, and will likely stay in office after these elections. In the past, all incumbent governments had failed to win reelection, and, in a lot of cases, lost their reelection bids by phenomenal landslides. This year, the political turnaround is remarkably low. The governing parties, PO and PSL, lost only five seats altogether. In 2007, the three governing parties had lost 79 seats (though PiS, the largest party in that government had gained 11 – the far-right lost all of its 90 members). In 2005, the SLD government had lost 162 seats and in 2001 the AWS had lost all 201 seats. As Poland’s level of economic development and standard of living catches up with that of western Europe, and the economic and social difficulties which fed anti-incumbent reactions slowly dissipate, voters are becoming much more supportive of incumbents and much less likely to punish them heavily at the polls. The PO government has been rewarded for Poland’s comparatively strong economic performance in the EU, the progressive rise in the standard of living and salaries, and the political, diplomatic and economic stability the PO has brought since taking power in 2007 from a fractious, divided government. PO, of course, benefited from ‘strategic voting’ from left-wingers and other Poles who feared that PiS could win these elections and win back power, an idea fed by the government which portrayed the battle as a straight contest between itself and PiS.

With PO and PiS having been the two largest parties in all elections since 2005, it appears as if Poland’s remarkably unstable political system has stabilized somewhat around those two parties with the PSL and SLD as smaller parties. However, while the current system might hold for a few years, I doubt that this system can be considered to be definitely implanted. After losing six elections in a row since 2006, it is doubtful whether PiS can actually ever form government again and, in the long term, survive in its current state. PiS’s national-conservatism still speaks to a large portion of Polish voters and there will always be a place in the political system for such conservatism, but a majority of voters strongly reject the party and Kaczyński’s government between 2006 and 2007 evokes bad memories of political instability and diplomatic isolation. Moreover, it is unlikely that younger Poles will endorse the same nationalist and social conservative views of their parents: this election showed it well. Unless there is some major economic collapse and the left is unable to rebuild, then it is unlikely that PiS will be able to return to power again in Poland. Kaczyński’s move back towards ultra-nationalism and hard-right conservatism hasn’t and will not do the party any favours. The most likely scenario, for the long term, is that PO will remain as the main right-wing party with some sort of new left mixing social democracy, social liberalism and anti-clericalism regaining political prominence while PiS declines into third or falls into divisions. The PJN split was an opportunity for PiS moderates to find a political space on the right between the liberal PO and the increasingly hard-right PiS, but it ended up being a jumbled attempt at doing so. Yet, such splits within PiS could become much more common if Kaczyński keeps an iron-hand over his party and keeps PiS from evolving towards more moderate positions.

PO’s victory is the reward of a grateful electorate for political and economic stability, a comparatively robust economy and a progressive increase in their standard of living. They have made mistakes along the way and not all is bright – unemployment is at 9%, inflation has crept up a bit and some reforms remain overdue – but, in general, the voters are happy with the way things are going. The PO lost just over 2% support and two seats in the Sejm. PiS lost roughly the same number of votes as PO, just over 2%. Proof of the continued political polarization of Poland – for the moment. But as mentioned above, it is hard to see PiS improve significantly or make a major breakthrough discounting any unforeseen event. PiS has a loyal and solid base which turns out in big numbers every election, but if it is to win back government any time in the near future PiS needs to break past its rock-solid base in rural eastern Poland and expand its support into urban areas and liberal western Poland – which is hardly likely, especially if PiS keeps harking to the right rather than slowly moderating its conservatism. There is also the problem that even if PiS was to breakthrough and win, say, 35-40%, it would be left rather isolated in the tough game of coalitions. The far-right which supported the Kaczyński cabinet until 2007 died in 2007 and isn’t showing any signs of rebirth. The PO, SLD and now Palikot Movement will certainly not cooperate with PiS in its current state. Of the current parliamentary parties, only the PSL which whores itself to anybody could perhaps realistically consider a coalition with PiS.

The spectacular success of this election was the maverick Palikot Movement, the anti-clerical and social libertarian movement led by former PO deputy Janusz Palikot. Palikot’s success shows the evolution of a part of Poland’s youth and broader society away from the social conservatism of the country’s governing elites and in favour of social liberalism. It remains to be whether or not the Palikot Movement is a one-election fad, or whether is will be able to solidly implant itself as Poland’s third largest party ahead of the older PSL and SLD. The party’s electorate is a bit all over the place. It did very well in traditionally conservative Lublin Voivodeship, but Palikot himself was born there and was originally elected for the PO in Chelm constituency. It performed better in urban areas, but rather interestingly did not win its best results in urban districts.

The SLD won its worst result ever, despite early campaign talk that the SLD could rebound a bit from the lows of 2005-2007 this year. In the end, thanks in large part to the phenomenal success of Palikot and the terrible leadership of Grzegorz Napieralski, it amounted to naught as the SLD received a major thumping with a large part of its new social liberal electorate in the urban centres abandoning the party. The SLD has, since its 2005 defeat, been totally incapable of rebuilding itself into a major alternative and Grzegorz Napieralski’s authoritarian leadership of the party in recent weeks hasn’t helped matters. The SLD still has some talented members among its ranks – former Prime Minister Leszek Miller returned to the Sejm after a 6-year absence. Napieralski himself has stepped down, and will therefore be making room for new blood. But after a heavy defeat and falling into fifth place, it remains to be seen whether the SLD as it presently incarnated will be the driving party behind the re-emergence of the Polish left which I predict will happen in the long run.

The PSL’s decent showing after Waldemar Pawlak’s pathetic showing in last year’s presidential elections is a sign of the party’s continued vitality outside of the personality-driven presidential elections. The PSL can still count on a disproportionately large base of support in rural Poland and a strong network of elected officials in local government. The PSL, which whores itself to larger parties in return for political influence, will likely remain part of the incumbent government.

In Senate elections, the PO won 63 seats against only 31 for PiS. The PSL won two, while two high-profile left-wingers won seats – the SLD’s Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz in Podlaskie Voivodeship and the SDPL’s Marek Borowski in Warsaw. Two independents were elected, one of whom is an ally of Wrocław mayor Rafał Dutkiewicz and the other of which was former Senator and filmmaker Kazimierz Kutz. The Palikot Movement, which supports the abolition of the Senate, did not run any candidates for Senate.

The map has evolved very little since the 2007 elections. Polish politics are divided both on a rural-urban axis and an east-west axis (or German vs. Russian-Austrian axis, for history buffs). In the 2010 presidential election, the PO’s support increased as the population of the settlement increased, with the party doing best in the largest cities and doing poorest in villages. The rural-urban divide breaks the east-west divide, because the PO did just as well in “eastern” urban areas (which were Russian or Austrian until 1918) as they did in “western” urban areas. Eastern cities such as Warsaw, Łódź or Kraków are reliably PO areas, even though they lie in territory which was Russian or Austrian until 1918. Still, the divide cannot be entirely laid down to rural-urban, because there is an unmistakable divide between east and west and the PO performs strongly in sparsely populated rural areas in western (German) Poland. The roots of this divide have been explored above, and they continue to be a potent factor in Polish politics.

It is truly a work of beauty to see the borders of 1914 replicated so closely in a Polish election in 2011. There are, of course, a few exceptions. The first exceptions are the urban areas, which are reliably liberal even if they fall in eastern Poland. The other exception, an eyesore for those who like their electoral maps clean, are the counties of Lubin and Polkowice in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. Lubin and Polkowice are important copper-mining areas, and the Polish mining giant KGHM is based in Lubin. PiS has, in some parts, a rather working-class base in part because of its penchant for economic populism and statism (however true it is in practice). The final exceptions are a handful of isolated, non-urban solidly PO or SLD-leaning counties deep in eastern Poland. These counties most often have large ethnic minority populations – Hajnówka County, which voted SLD, is heavily Belarussian (and has a big timber industry). Other areas have large Ukrainian or Lithuanian populations. Poland’s German minority, which benefits from special linguistic and cultural rights and has its own political party, is concentrated heavily in Opole Voivodeship. The German Minority won 8.76% in Opole this year, down slightly from 2007 when it had lost one of its two seats in Opole. The German population is concentrated to the east of the city of Opole (Strzelce, Krapkowice, Opole and Olesno counties mainly, also in Kędzierzyn-Koźle, Prudnik and Kluczbork counties).

My apologies for the delay in putting together this post. Other posts on the weekend’s elections will follow.

Posted on October 12, 2011, in Poland. Bookmark the permalink. 4 Comments.

You used whore or whorish 4 times to describe PSL. I think we get the idea.

Informative and a nice more in depth discussion

of the election results than one usually sees in

the media. It helps one to feel like it gives a better

understanding and appreciation of the significance

and implications of the voting outcome than you

otherwise would get.

Fascinating. To read all other international media reports of this election I would have concluded it was “boring” or “predictable”, when obviously it was anything but.

I have one question though: it seems like Polish electoral politics is very dynamic, and voters take shrift with parties seen to have failed or stopped delivering. So who is still voting PSL, and why is there voter base considered solid? Do they deliver anything when they enter coalitions? The description of their platform on their wikipedia page seems suitably flexible, so I can see why they make good coalition partners, but why don’t their voters go elsewhere, as all the other parties’ voters seem to on occasion? Would be grateful for any insight you have on this.

The PSL used to have a much wider electorate in the 90s as well, but it is true that they have been the most resilient of all parties. Their success seems to be based on their continued strong base in local government, its whorish policies of “centrism” which seems to not alienate a lot of its core supporters. Its voters are apparently wealthier landowners (kulak types) mostly in Russian/Austrian parts rather than rural “redneck nationalists” like PiS, and the map shows that the party has some weird concentrations of support. I suppose this electorate is not as likely to switch to PO, too urban/too liberal/too German Poland; or PiS, too redneckish. Only a theory, though…